Ai Weiwei, the most prominent Chinese artist-architect in China, grew up in exile, in the remote desert area of Xinjiang. His father, the famous poet Ai Qing, was accused of anti-Communist activities during the Cultural Revolution and was sent into political confinement along with his family, forced to live in a shack without running water or electricity. In an interview, Ai Weiwei told me that he feels no rancor towards the regime, only perhaps some anxiety about the speed at which his country is changing. He is in fact one of the few Chinese intellectuals intent on understanding and discussing what is going on today in his country. I met him in Beijing, this past September, under a gray, polluted sky, during a symposium organized by Art Basel at the National Museum. The gathering — whose general theme was the Chinese museum system — quickly became a kind of harangue by critics and curators like Huang Du and Fei Dawei who decried the limits and inadequacy of contemporary art institutions in China. Chinese artists benefit from the extraordinary level of Western interest, but the general feeling is that this immense Asiatic region represents simply the latest Mecca for an army of speculators. Fei Dawei, in particular, argues that the international market is affecting the development — and perhaps even the direction — of the entire artistic scene. The harshest declarations were by Ai Weiwei; on the one hand he questioned the use of discussing the future of China’s museums with the international jet-set, and on the other, he invited the participants to discuss issues which he considers much more important in China today, like freedom and civil rights.

Market and Regime

The West tends to forget that despite the economic reforms of Deng Xiao Ping, China, now more than ever, is in the hands of a despotic, nepotistic, and thuggish Communist Party. Artists and gallery owners have to deal with censorship every day; exhibitions are shut down, works of art are banned, and catalogues confiscated. In May, two artists who were invited to a show in Shanghai were arrested because their work contained unspecified ‘pornographic’ elements. While many Western galleries, not all of them of the highest level, hunt for so-called new talents in order to satisfy the ‘yellow-fever’ of a growing number of collectors, in China a few critics, curators, and artists are trying desperately to create at least the semblance of an art scene. It is understandable that during this phase people like Fei Dawei are anxious about the growing aggressivity of the international market, which for the last few years seemed literally boundless. According to Zhang Wei, the director of the Vitamin Creative exhibition space, the market’s willingness to absorb anything from China is affecting the very quality of the work. Perhaps this is why, despite the growing number of galleries that open every day in neighborhoods dedicated exclusively to art, like Factory 798 in Beijing or the Moganshan Road District in Shanghai, it is not easy to find high quality exhibitions in China, or works of art that are not created expressly to satisfy foreign tastes and expectations. What has been missing up to now and which is slowly being constructed, is an autonomous critical platform, an articulated network of critics, historians, curators, and gallery owners able to explain Chinese art from the inside, and not through an extraneous cultural model.

Shanghai

Many things have changed in this immense country since the days Frank Uytterhaegen and Ai Weiwei organized small, semi-clandestine exhibitions in the apartment of Hans Van Dijk in Peking in the early nineties. A year ago in Shanghai, for example, the contemporary art center MoCa, a place that has little or nothing to envy even when compared to the most modern western museums, opened its doors. Set in a verdant park within the perimeter of “People Square,” MoCa has undertaken — among other things — a kind of systematic analysis of the country’s artistic landscape. Every two years, a ‘thematic,’ panoramic exhibition of Chinese art, entitled “MoCa Envisage,” will be inaugurated alongside the Shanghai Biennale. “Entry Gate: Chinese Aesthetics of Hetereogeneity,” the first show of the series, was inaugurated this September, and quickly became one of the most interesting events of the variegated and often mediocre Chinese artistic landscape. Curated by Victoria Lu and a group of collaborators, the show attempts to capture the heterogeneity and complexity of China’s contemporary art, and at the same time underline its uniqueness with respect to the West. Some things in the show don’t work perfectly, and perhaps the relation between the contemporary and the traditional — an important issue for countries in this region, like for example Japan — could have been treated in a more interesting manner. Some works were superficial, such as the approach of the artist Wang Mai, with his lantern attached to the ceiling, or that of Tian Wei’s sign painting, or the performance by the trio made up of Dant Den, Victor Liu, and Tim Chen, atop an illuminated box. Even so, all in all, “Entry Gate” manages to create a curious and varied image of China’s artistic scene, revealing the vast distances between certain artists, for example between the young video-artist Yang Fudong and the seventy-year-old artisan sculptor Zhou Changxing. There is also a curious contrast between the more formalist artists from the North, such as Ai Weiwei, Zhang Wang, and Tian Weil, and those from the South such as Lu Fusheng, Zheng Zaidong, and Huang Chih Yang who, as Victoria Lu’s catalog states, are more interested in creating a poetic, lyrical atmosphere.

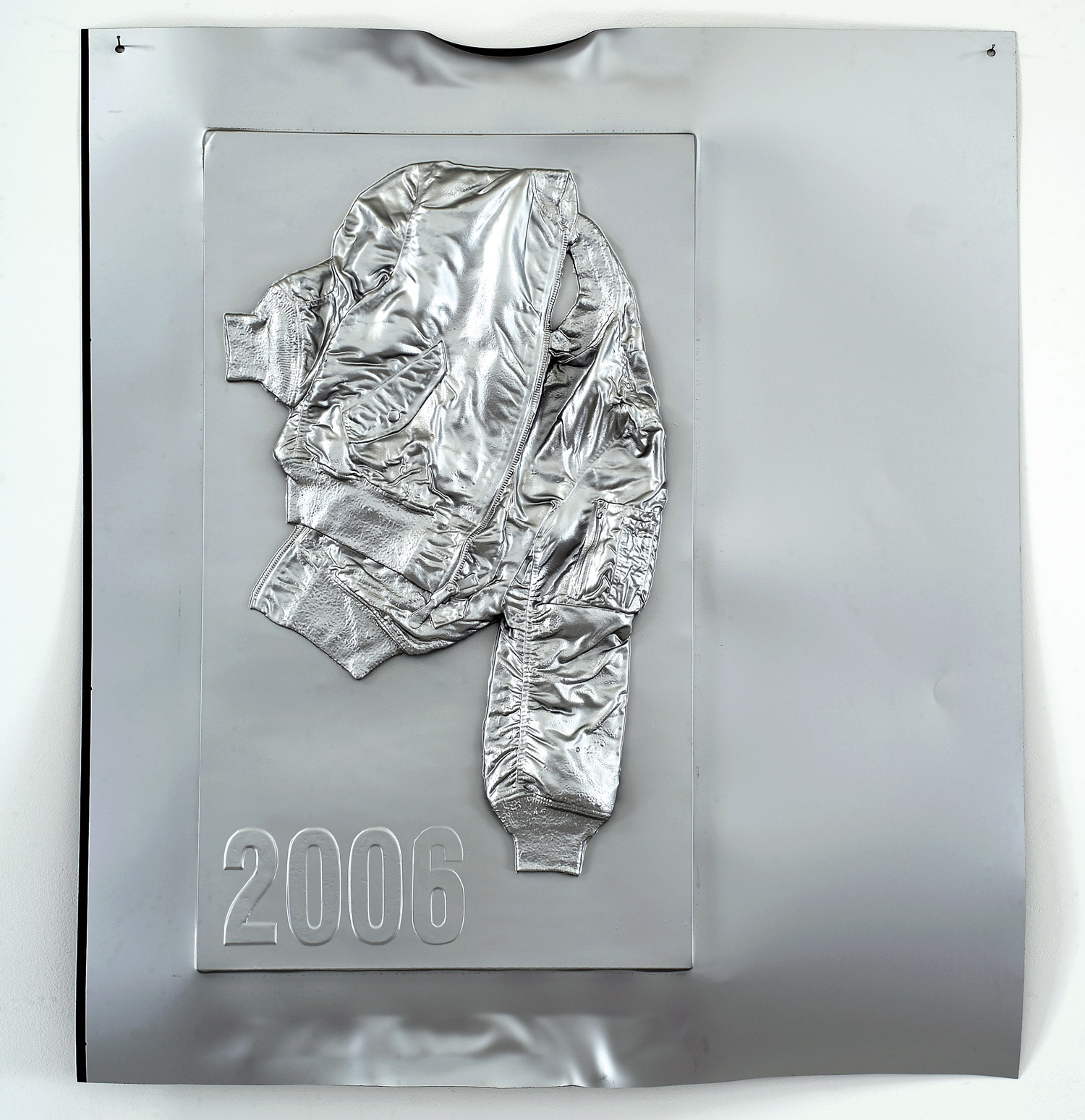

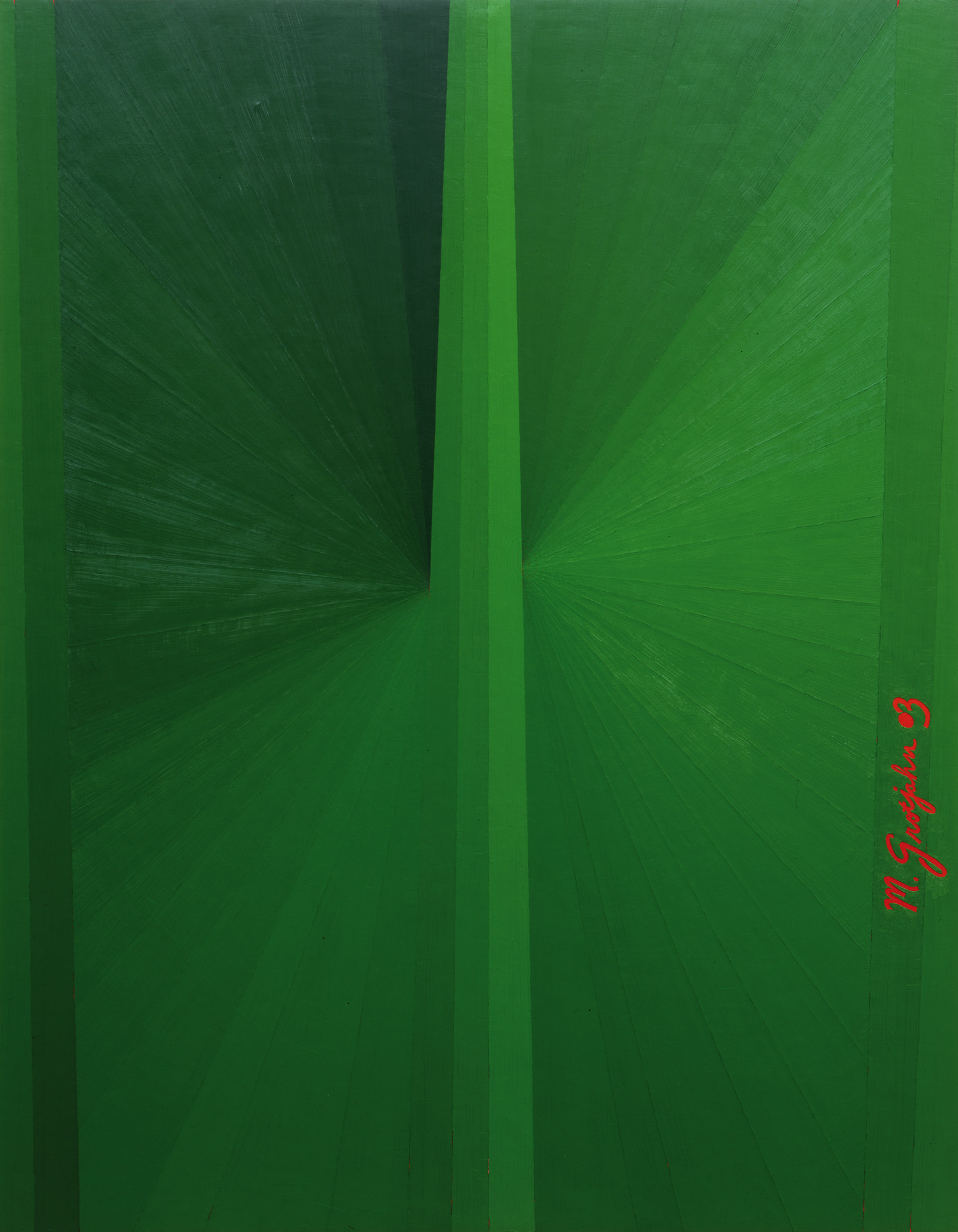

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of the sixth edition of the Shanghai Biennale. The objective of the curatorial team, which was directed by Zhang Qing, and includes Huang Du, Gianfranco Maraniello, Shu Min-Lin, Wonil Rhee, and Jonathan Watkins, was to investigate the cross-pollination between art and design, and shed light on the important role of design in filling the gap between art and life. This is an interesting and central issue in a culture like this one, which has historically relegated design to a privileged art form. Even so, the works selected rarely demonstrated any link to the basic curatorial idea. In general the exhibit — which fills the various floors of the Shanghai Art Museum — comes across as a jumble of works, incapable of dialoguing not only with the chosen theme, but also with each other and with the restricted space in which they are exhibited. It is a generic and discontinuous show, which wanders from dated works like Joe Scanlan’s “Ikea Furniture” (1999) to others which are simply mediocre, like the paintings of Yang Qian and Zhong Biao; from obvious choices, like the works of Sylvie Fleury, Julian Opie, and Yoshimoto Nara, to inexplicable ones, like the photographs of Ron Terada and Caro Niederer, or the sculptures of Peter Callesen and Gerda Steiner & Jörg Lenzlinger. The presence of works by Matthew Barney, Jorge Pardo, Annika Larsson, Hans Ope de Beeck, Atelier Van Lieshout, Patrick Tuttofuoco, and a few others is not enough to save the biennale from an unpleasant “second-rate art fair” effect. There are too many examples of Asian artists whose work closely resembles that of well-known western artists, like the Korean Cody Choi, who creates paintings à la Richter, or the photographer Wang Guofeng, who creates a Chinese version of the work of Gursky, or — to give only a few examples — the work of Qiu Anxion, reminiscent of the video animations of Kentridge. This Biennale does not accomplish the aim of informing the public of the most interesting experimentation going on in China, nor does it succeed in presenting a point of view about art today.

Squandered hopes and opportunities

In a country where the showing of art is done almost exclusively in private galleries, biennials of this sort are, to be honest, a bad deal. The opportunities to put together a wide-ranging exhibit capable of proposing a reading of developments in contemporary artistic exploration are few. And, other than the international market for hypothetical ‘new talents,’ there are few structures in place with the purpose of stimulating and supporting young artists. Among these, one in particular must certainly be mentioned: BizArt in Shanghai, perhaps the only Chinese nonprofit in our sense of the term. BizArt is an association composed almost exclusively of artists, and directed by the art historian Davide Quadrio and the artist Xu Zhen. With its 16,000 square feet space in the Moganshan Road District, this nonprofit represents one of the most interesting realities of China today. Financed by its members and private sponsors, BizArt works to promote and create new audiences for Chinese art by organizing exhibitions and cultural events. In its eight years of existence, the association has underwritten and shown works by artists who have subsequently become stars, like Yang Fudong, Shi Yong, Zhao Bandi, Song Dong, Yang Zhenzhong, Gu Lei, Song Tao, Liang Yue, and Hu Jieming, among others. Besides presenting three or four events per month, Davide Quadrio and Xu Zhen organize two residencies for Chinese and Asian artists.

Another interesting exhibit space is Vitamin Creative in Guangzhou which, despite not being a nonprofit, tries to preserve its role as an independent institution. Its founders, Zhang Wei and Hu Fang, two of the most notable figures on the Chinese artistic horizon, state, “The essential objective of Vitamin is to understand what contemporary art in China is, and what contemporary art can mean or accomplish in the Chinese context.” By organizing exhibitions and especially workshops, Wei and Fang are attempting to create spaces for reflection and real forums for discussion. Currently, Vitamin is organizing a series of workshops in a mountainous area entitled, “Fools Move Mountain.” The basic idea is to bring together artists, philosophers, architects, and designers, in order to more fully and deeply understand the Chinese system and its rapid transformations.

Obviously, in Shanghai and Beijing there are few quite good galleries like Shanghart, Eastlink, Long March Art Foundation, Chinese Contemporary, Beijing Commune etc. I am not trying, disingenuously, to question the important role, both cultural and economic, of these galleries in defining and constituting the nascent art world of this bizarre Communist country. It is however true that in China there’s no primary market system yet, and — at the moment— the secondary market is a mess. This is not enough, as Fei Dawei repeated several times during the meeting organized by Art Basel. People in China should hope that sooner or later the art world will speak of contemporary art in China, and not of ‘contemporary Chinese’ art, as a trendy market phenomenon. Until China is able to break out of this stereotypical mold as an ‘ethno-avant-guarde,’ its art scene will not be autonomous, or even, ironically, a safe investment for collectors.