“Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011” at MoMA PS1 is a vast group show that won’t let you look away. Some context: in 1991, a US-led coalition intervened in the Persian Gulf after Saddam Hussein annexed Kuwait. Along with the military, the media came to the Persian Gulf, presenting a radical, biased vision of the Middle East that is deconstructed here through more than 250 artworks.

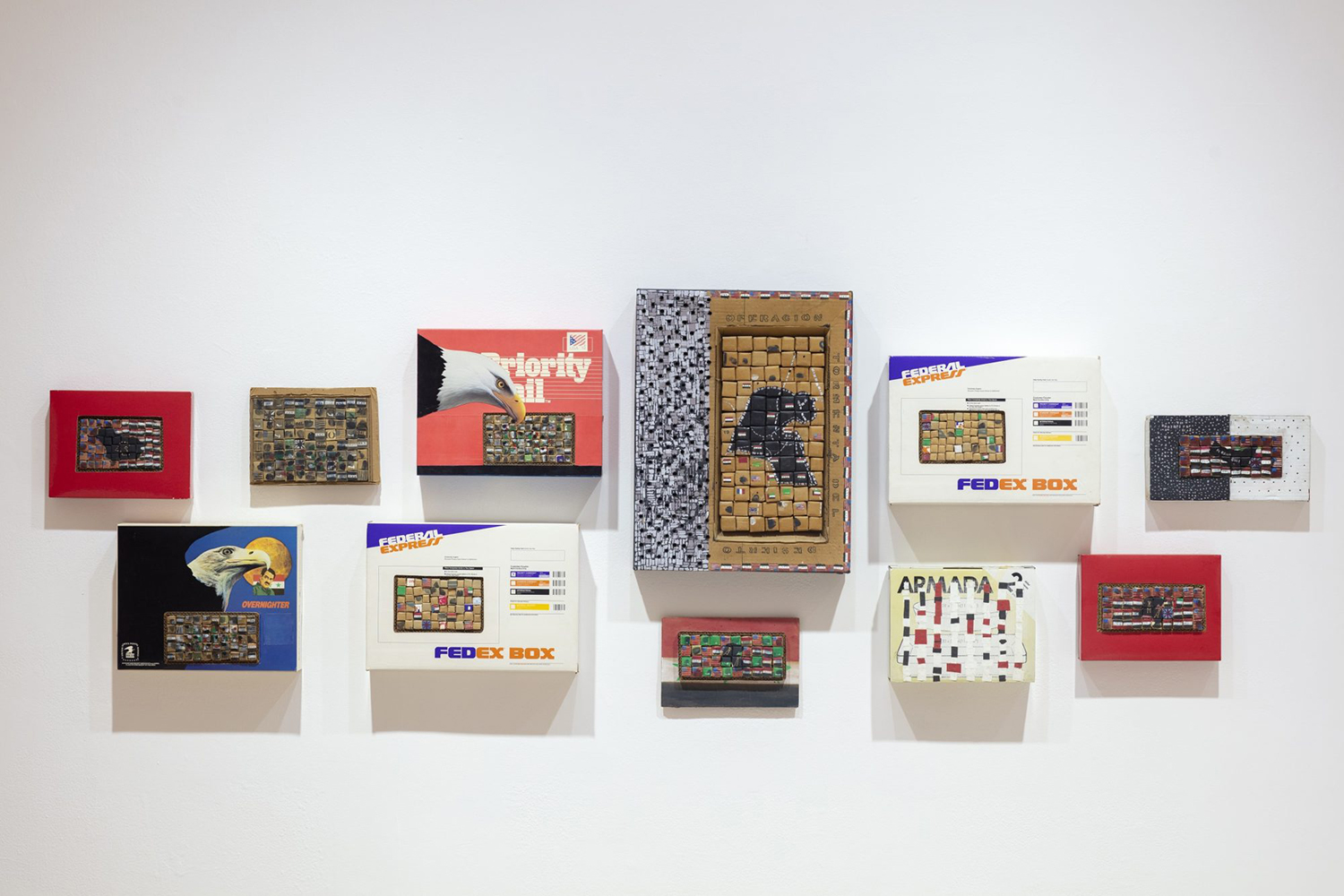

The Gulf Wars were the first wars to be broadcast live on television, adding real-time suspense — hence entertainment — to the horror. Some called the Gulf Wars the Video Game Wars. Anyone could tune in and see, “Live from Bagdad,” the desert burn, the cities shatter, and the local population run away in rags and tears amid the dead. The constant flux of information fed our prurient nature. Behind our screens, we felt safe, maybe satisfied; at least we didn’t feel responsible. But the images, documents, and artworks featured in this exhibition are like ghost songs whispering from the past, asking for today’s viewers to bear witness.

Wandering through the exhibition, I found it hard to connect art and war together. Isn’t violence the negation of art? Or is it the desensitization that occurs while we lounge watching television (Martha Rosler, Thomas Hirschhorn, Michel Auder)? Can art teach us about the extremes of our inhumanity? On the other hand, maybe war can awaken our most fundamental and primitive emotions.

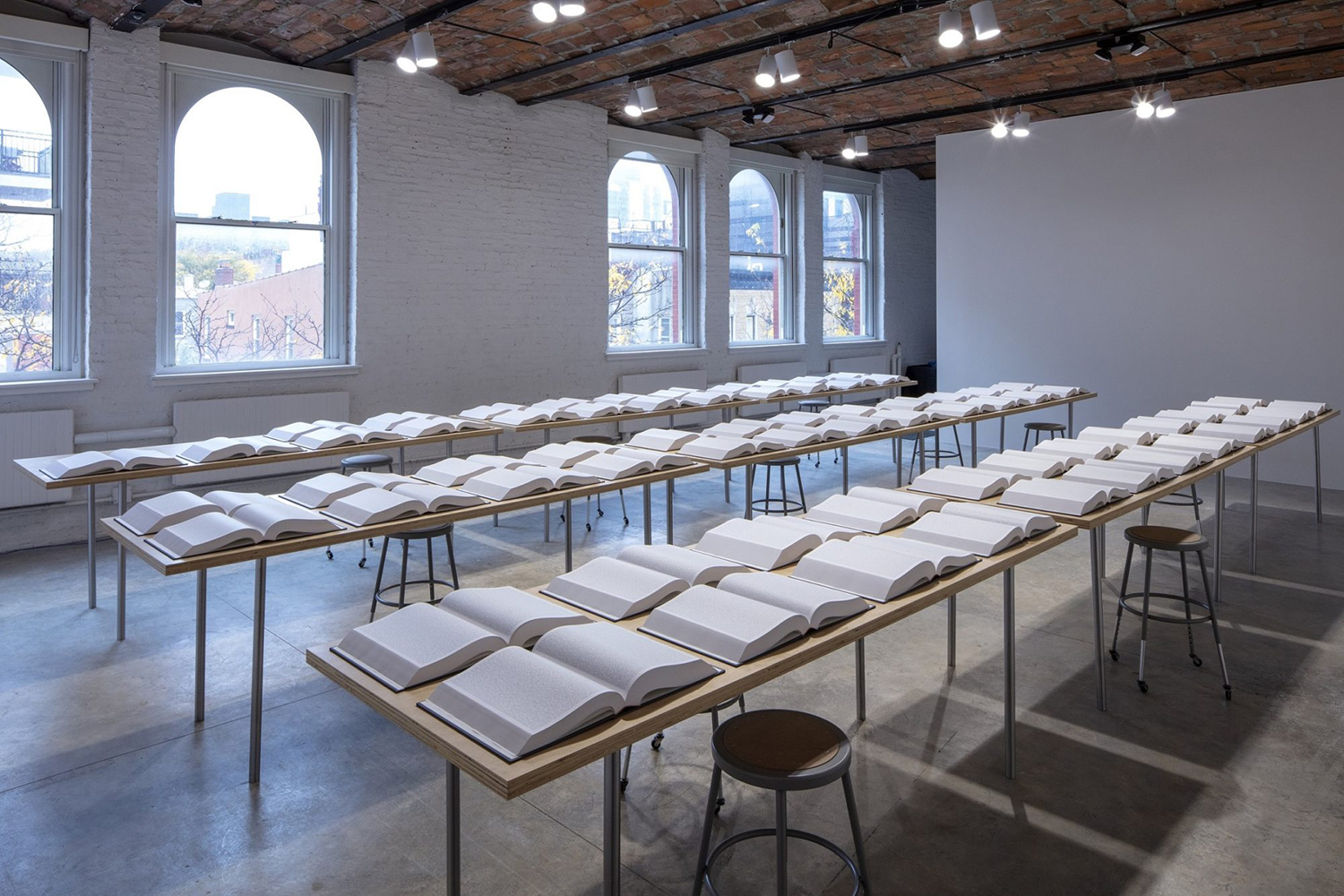

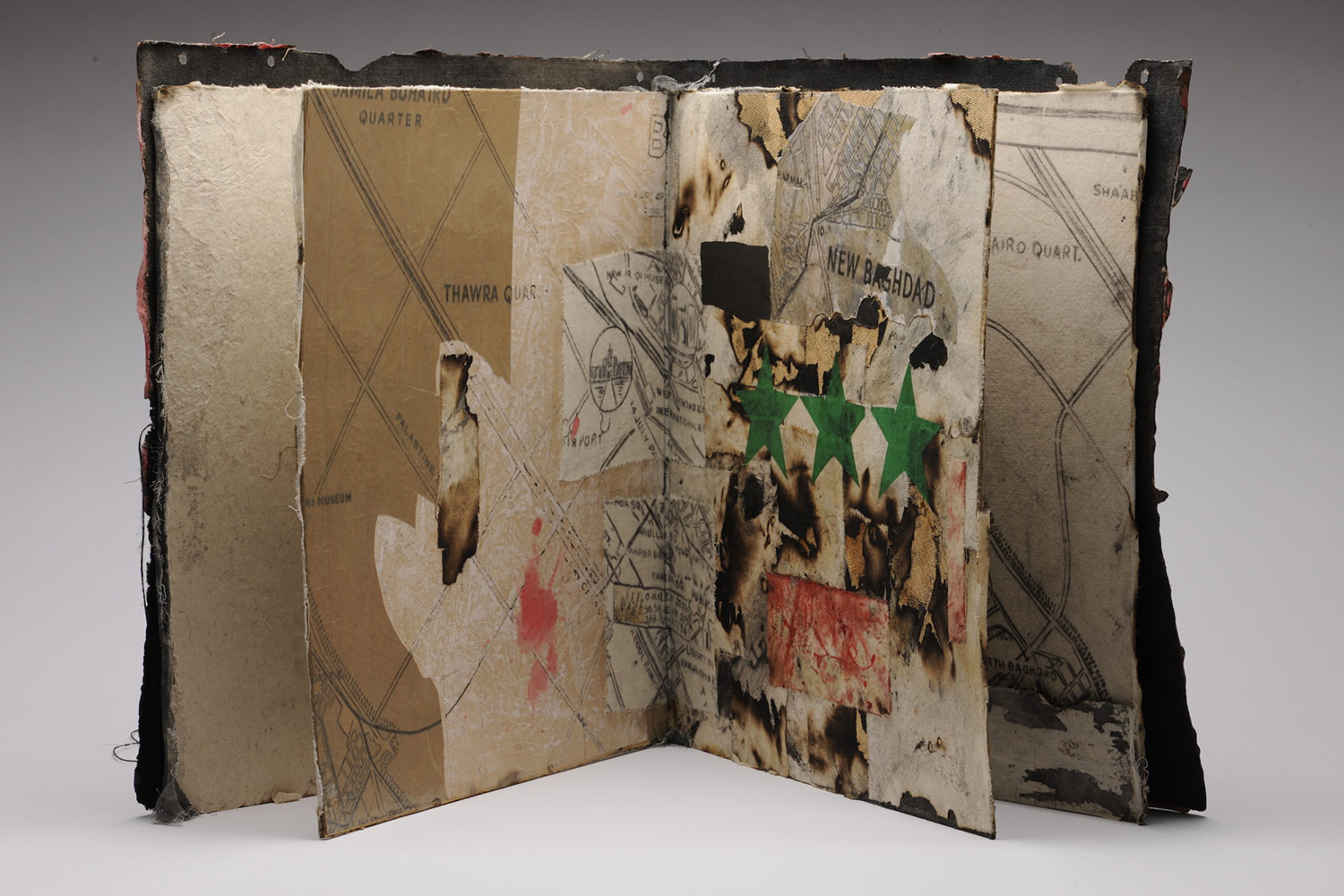

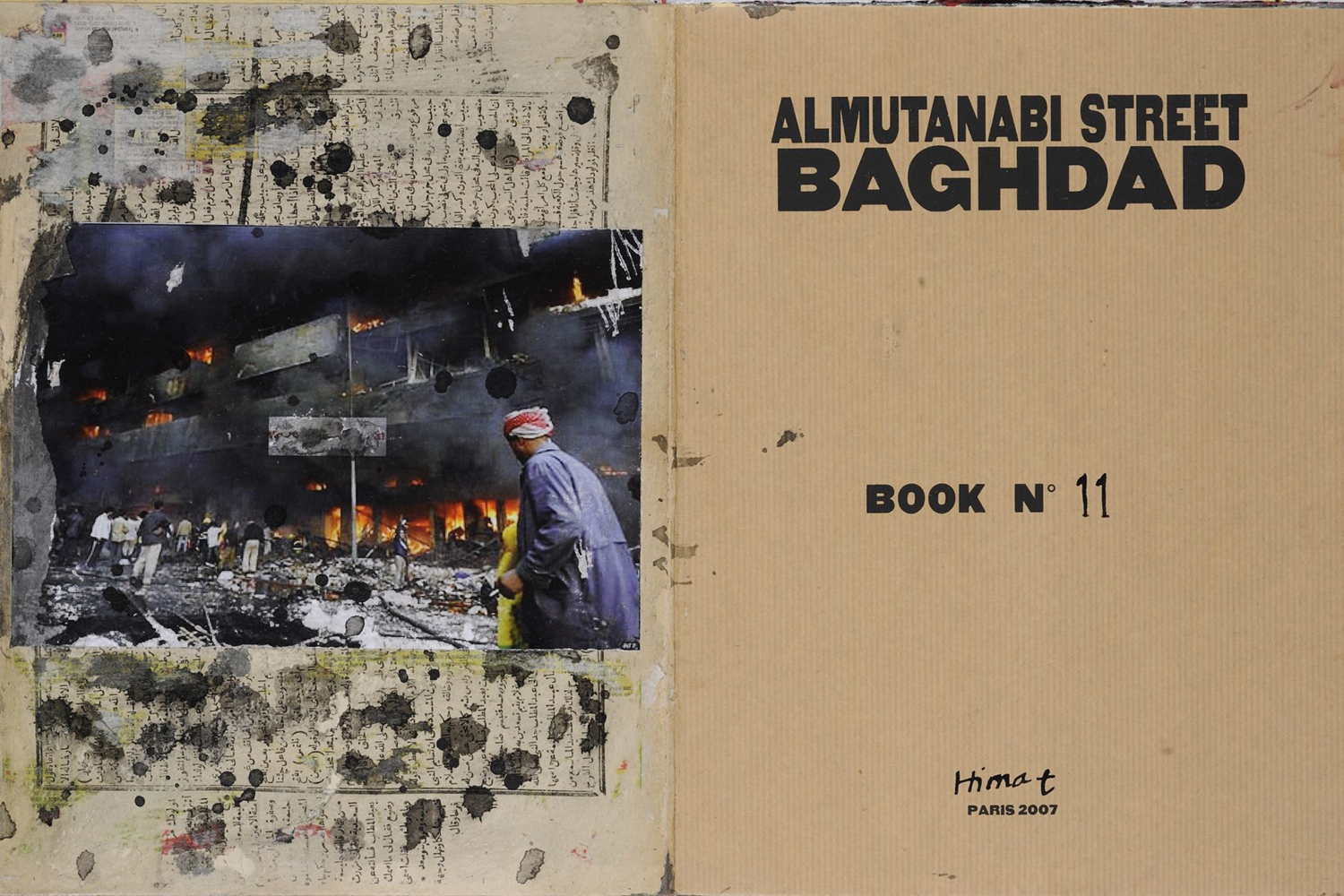

What’s remarkable about the exhibition is that it includes the perspectives of both Iraqi and American artists. American artists tend to criticize the systematic violence perpetrated by their government, whereas Iraqi artists often use abstract expressionism to represent their trauma. The show tries to undo stereotypes of Americans and Iraqis through the prism of art, but, in the end, horror makes no distinction. “Theater of Operations” is itself like a battlefield: a chaotic zone of emotions and information, of panic and terror.

Thomas Hirschhorn makes sure we are not left unaffected. His film Touching Reality (2012) shows a woman’s hand swiping through digital images of mutilated Iraqi bodies. If the content is gruesome, the hand reminds us that we are safe, powerless, witnessing horror behind a screen. Fascinated, hence guilty. War is a theater of violence, and America, the creator of modern entertainment, excels at packaging and broadcasting it. I’m afraid the exhibition portrays the American army and the American media as two of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, galloping before a hellish inferno. I think the truth is elsewhere.

The show’s masterpiece is Monira Al Qadiri’s film Behind the Sun (2013), which comprises film footage that the artist acquired from a Kuwaiti man who had driven his car into the burning oil fields (set by retreating Iraqi troops) to record the devastation firsthand. Putting himself in harm’s way, he filmed the fires in close proximity, producing a far more intimate vantage on the catastrophe than those represented in the media. Al Qadiri overlaid this footage with a spoken-word soundtrack, sourced from old TV programs, in which Arabic religious poetry describes scenes from nature. The result seems to be an ode to the apocalypse. Let us burn all the wealth, all the land, and let the smoke reach the stars like a burnt offering.