People want to see images that reflect their reality, but media distortions and the pace of digital technology have warped the very parameters of what reality encompasses. “The Real Show” grapples with contradiction. The structure is conceived as an episodic model that can readily evolve into spin-offs (which it will, as it travels and morphs at subsequent venues in Metz, Paris, Bucharest, Riga, and Ostrava). The exhibition navigates between private/public, entertaining/political, vernacular/institutional — tracing how popular gestures circulate and burgeon into wider cultural instruments.

The “pilot episode” at CAC Brétigny focuses on our “ecosystem of representations” and, as such, is “conceived reflexively: the form questions the subject and mirrors the function of certain media,” explains Céline Poulin, exhibition co-curator and director of the venue. Artists deploy podcasts, video reappropriations, and stylized caricatures, revealing how digital platforms — and their distortions — shape and reshape the collective imagination.

Hanne Lippard’s six-speaker piece I Missed Your Call More Than I Missed You (2020) greets the visitor, rendering her articulation of the word “anonymity” increasingly absurdist gibberish as she shifts the syllables. Anonymity, or the absence of authorship, is “both a refuge and a refusal,” Poulin notes. Adjacently, Christian Jankowski explores the relationship between communal creation and individual bodies in his video Rooftop Routine, the choreography of which Poulin sees as a kind of prescient prelude to TikTok. A scattering of colorful candy cane–striped Hula-Hoops allow the visitor to participate (which local kids did, shimmying gleefully).

Most of the featured artists here are contemporary, but Argentinian Luis Pazos and American Martha Rosler provide a sense of reverse-continuity for these themes going back half a century. Pazos’s black-and-white photographic series La Cultura de la Felicidad, in which all faces are masked by an “unchanging smiley face,” as Poulin puts it, evoke the emoji, while Rosler’s deadpan black-and-white 1975 video Semiotics of the Kitchen, in which she demonstrates domestic functions of the pan and the rolling pin, are like a YouTube parody before YouTube.

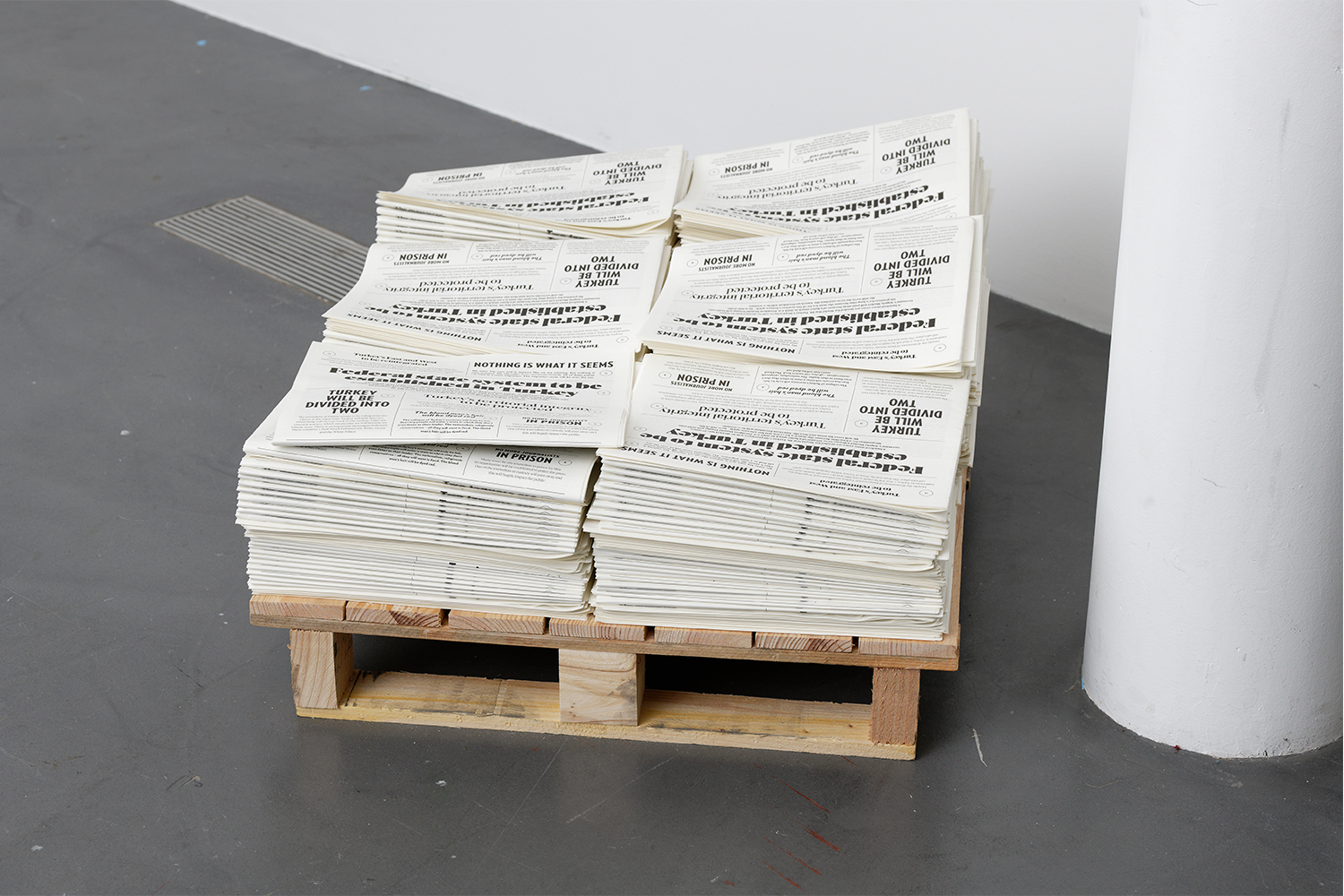

A magazine rack displays copies of Narrative Machines, a faux-but- real Google-translated publication by Moroccan artist Ghita Skali (in collaboration with Ayla Mrabet and Kaoutar Chaqchaq). Riffing on pseudoscience, wellness, and women’s magazine tropes, its cover iconography includes a maxipad and a syringe, plus the promise of exciting content like “Special Quiz: Anger or Hot Flash?” Inside, among other things, is a themed playlist that includes “Why Does It Hurt When I Pee?” by Frank Zappa and “Puke and Cry” by Dinosaur Jr. Nearby is a very different publication: stacks of Aslı Çavuşoğlu’s Future Tense, a sixteen-page black-and-white leaflet containing political prognostics (“Writers and Painters Will Not Be Able To Enter Turkey”) that blur the boundaries between the probable and improbable.

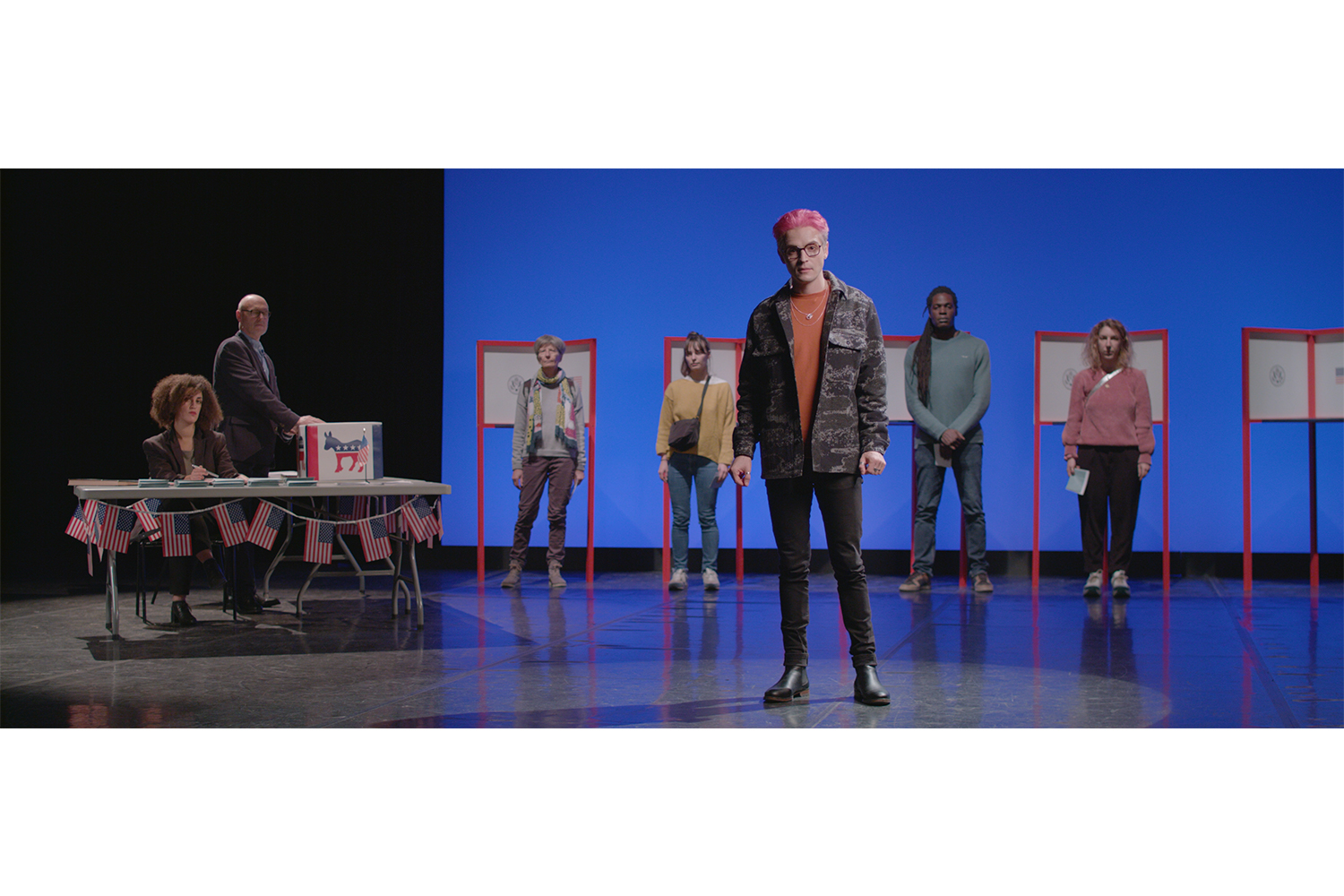

Meanwhile Virgile Fraisse’s How to Hack a Democracy (2021) video plays on loop with a slightly on-the-nose monologue about apathy around data breaches and the transformation of people into “units of culture.” A black-box viewing room allows the visitor to peruse and select from different videos, among them Zeyno Pekünlü’s How To Properly Touch a Girl So You Don’t Creep Her Out? (2015), a cringe-inducing scrutiny of masculine panic, skewering the laughable male figures who perform the worst of heteronormative male toxicity. Back outside the black box, Nora Turato’s poster series uses snippets of quotations decontextualized from their sources, creating pointed humor against colorful backgrounds. Her “i try not to think about it” poster might as well be the mantra of our lifetime.

Cumulatively “these works tellingly reflect the mechanisms that orient societal behaviors,” Poulin states. “They make us laugh, but they are also rather chilling.”