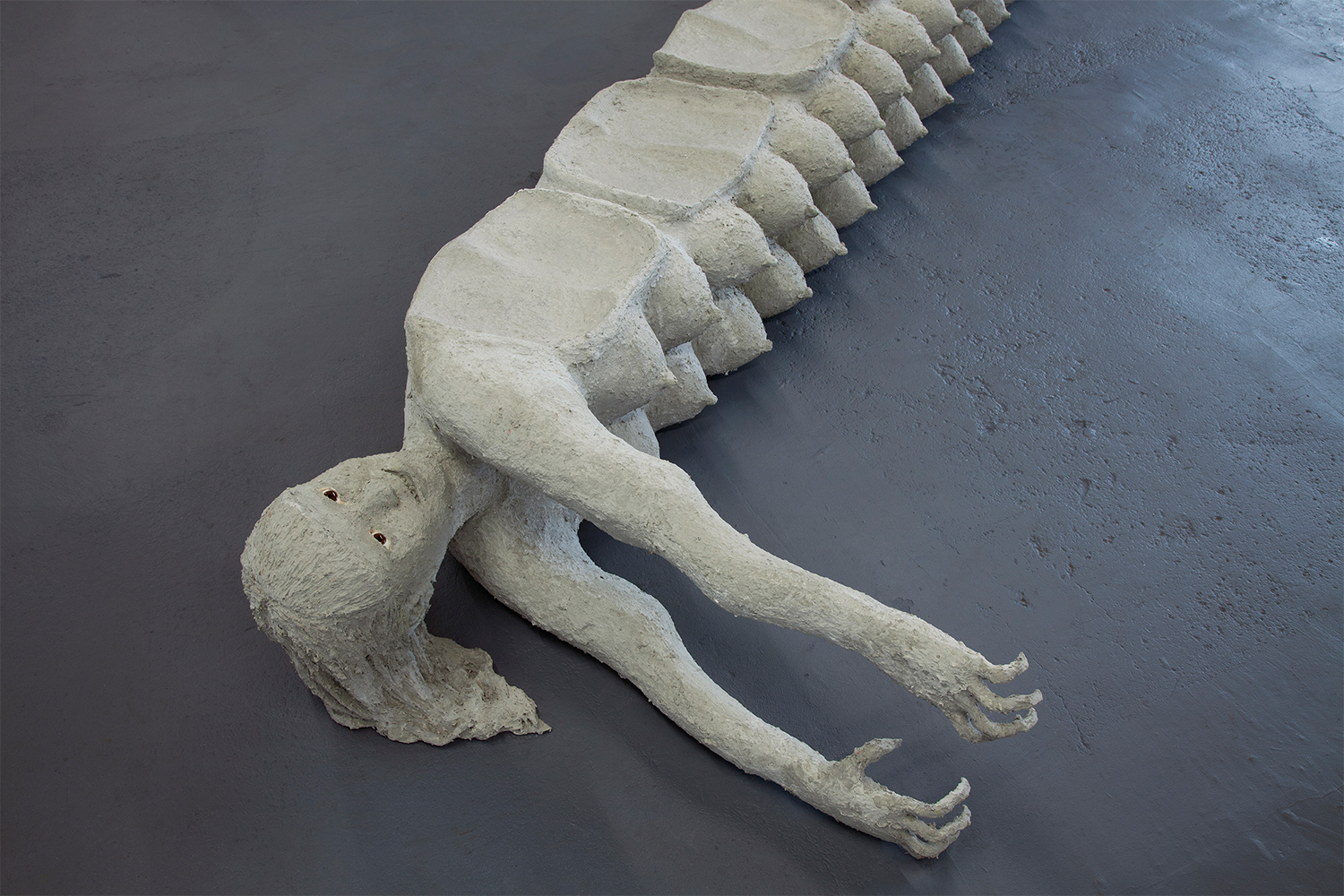

Caroline Kent’s installation at the MCA Chicago comprises two dimly lit spaces dressed to evoke studies: one space includes an open writing desk credited as a collaboration with the artist’s husband Nate Young, while the other is characterized by shelves of bound volumes with abstract, geometric paintings on their covers and spines. A correspondence in every sense of the word is suggested by enigmatic clues and easy-to-miss details that often mirror and echo the arrangements of the adjoining gallery. A lively synthesis of noir, sci-fi, domestic, and futuristic sensibilities elicits associations to the outlandish narratives around which “escape room” entertainments are organized or the intrigue of puzzle-based video games presented in surreal, otherworldly settings. Immersive décor in suggestive shades of green bridge allusions to nature and artifice — one could be called “hunter” green, while another bears the sticky intensity of arsenic dyes from the nineteenth century. These flatly verdant infernal offices are presented as spaces of analysis; even the miniature concrete Silent Sentinel sculptures (all works 2021) resemble the ethnographic tchotchke that crowded Sigmund Freud’s London offices.

And surely what Kent proposes in her selection of new work on 3,4 view is precisely an analysis — one that traverses the linguistic, the corporeal, and the epistemological tethers by which language and bodies often occur as coextensive in contemporary life. That is, Kent’s process of abstraction combines hieroglyphic flatness in allusions to figures with protean alphabets in meltdown. The writing and reading to which these rooms are intended deal in oblique encoded communications that substitute the embodied speech act.

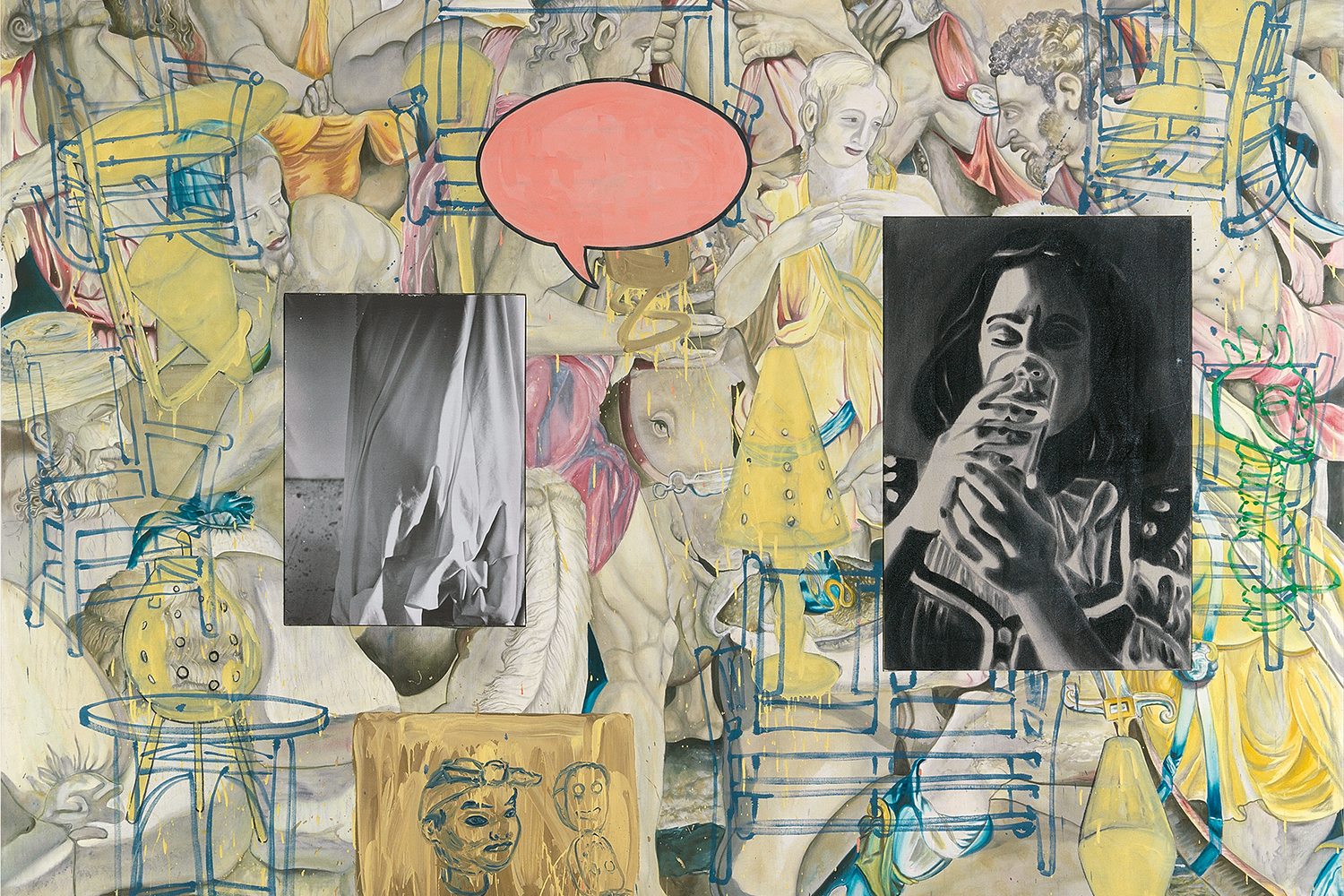

The moody theater of these installation environments contextualizes a series of unstretched scroll paintings with black grounds and tangles of flatly painted shapes and glyphs in the manner for which Kent has been celebrated for several years. The layered, dynamic compositions serve to demonstrate that abstraction operates as an ever-expanding project of language, whose complex grammar has been developed across global cultures, historical periods, and navigations of regulated identities. We gather across time features forms in poison green and tinted orange that interlock as cleverly as well-kerned typography. Mostly Kent’s nuanced écriture lacks translation, which is advantageous in order to observe the mechanics of how language operates — strung together into thought, practiced into eloquence, repeated into ideology — rather than contending with a particular literary content.

One clue Kent reveals, via wall text, to be an organizing principle in the work is a fanciful narrative about telepathic twin sisters that informs her decisions. And yet these characters are scarcely represented in any visual way within the exhibition. Perhaps the network of artificial plants that double as speakers and emit a gently crackling soundtrack — each is titled Untitled (Frequency) — indicates their psychic communiqués. A large nearby canvas roiling with gray-scale shadows and titled A scheme on how to stave off desire with distraction, acrylic on unstretched canvas, brought to mind the perverse longings of the sisters in Jean Genet’s The Maids (1947); it may be that Victoria and Veronica (as Kent has dubbed them) are mischievous at least, and perhaps dangerous to the symbolic orders that preside over the developed world.

Kent focuses on the internal logics of linguistics that precede the production of meaning in order to reckon structurally with the ways value systems are established, thus better illuminating the justifications around the lives, jobs, genders, and interior psychologies that are made to matter within those systems. In a sense her paintings are protest signs — not in direct response to one or another political agenda, but an interrogation of a prior state from which the articulations of such politics proceed.