Gordon Hall: Can you tell me about the origin of your Torrington Project, the upcoming event, and the book project? Where did it start for you?

Tom Burr: So, yes… it’s been brewing for a long time — maybe longer than I realized, many years in fact. I’ve wanted to play with space like this, to be able to have works that I’ve made over the years share the same air and be in dialogue with each other. That’s part of it. The other aspect is a sense of dissatisfaction and frustration with the systems I found myself entangled in, and wanting to create something different that would allow me to think and work differently.

More recently, three plus years ago, I actively started to pursue finding a space. I knew it wouldn’t be New York — it should have a distance from all that — and I was already living much of the time in northern Connecticut, so the choice was clear to me that it would be Torrington.

GH: I don’t think people realize how rare it is for artists to see our own work after it is initially presented! Especially with large sculptural work, site-specific work, we may see it once and never again. Or never in proximity to other works from other times, other projects. So, when you showed me Torrington it immediately made so much sense to me — artworks are physical things in space and no amount of documentation can describe what they do when we are with them, among them. So, I really get the impulse to pursue this.

TB:You’re exactly right. So often, especially when I was younger, my exhibitions were in Europe, or places that I did not live in, and so the sort of separation anxiety, of leaving the work behind, and relinquishing some degree of control perhaps, but also of not being able to linger with the work — this was often painful and frustrating for me. Works would get forgotten, not carried forward. And when I started Torrington Project, this was on my mind, this idea of being able to linger with my work, from both the past as well as the present, and to buy myself some time as well as space.

GH: Simultaneously, Torrington is a temporary endeavor — by the time this goes to print it will have been dissolved. I am curious about how you are approaching the book you are making with Primary Information about the Torrington Project, to be published next year. It will function as both an archive of the project and an extension of the space and what took place there, while widening the conversation to include multiple voices and perspectives.

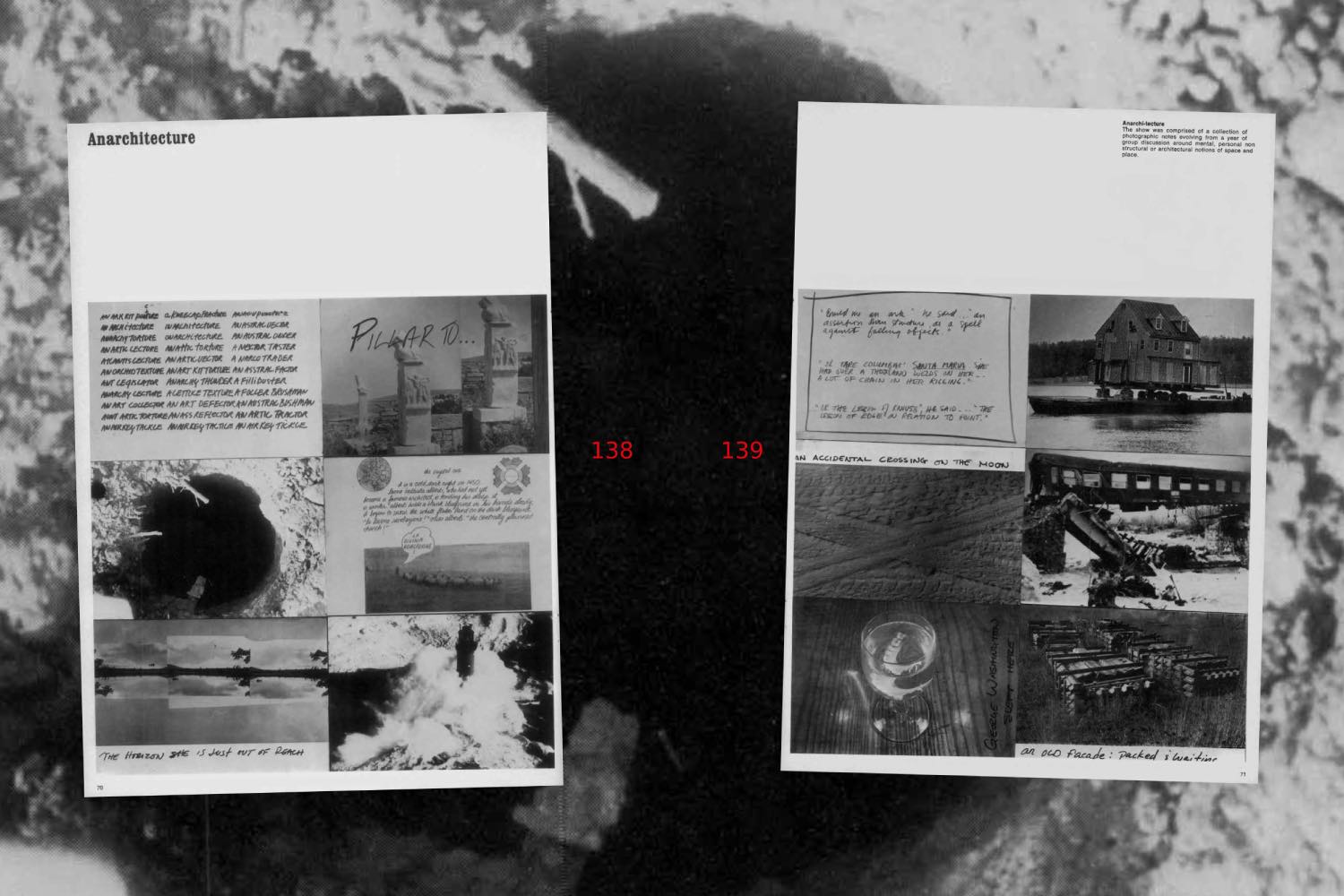

TB: I always knew that I wanted to make a document or a book as the final stage of the project. My ideas for the form it could take have evolved over the time I’ve been in Torrington, and now we have really embarked on the book process, just as the physical space is about to dissolve. I like that transition. I like this evolution of a physical, architectural space folding itself into book form. And rather than trying to create a document of the whole project, and to faithfully “picture” the space, I started to sense that I needed to create an experience in the book that was analogous to the space itself. This led me to invite Maria Hassabi, Nick Mauss, and yourself to participate, so that the whole stage set of it all, both in the physical space of the building and the physical space of the book, would be engaged in different ways and be interconnected.

GH: Where did the idea of including live performance originate?

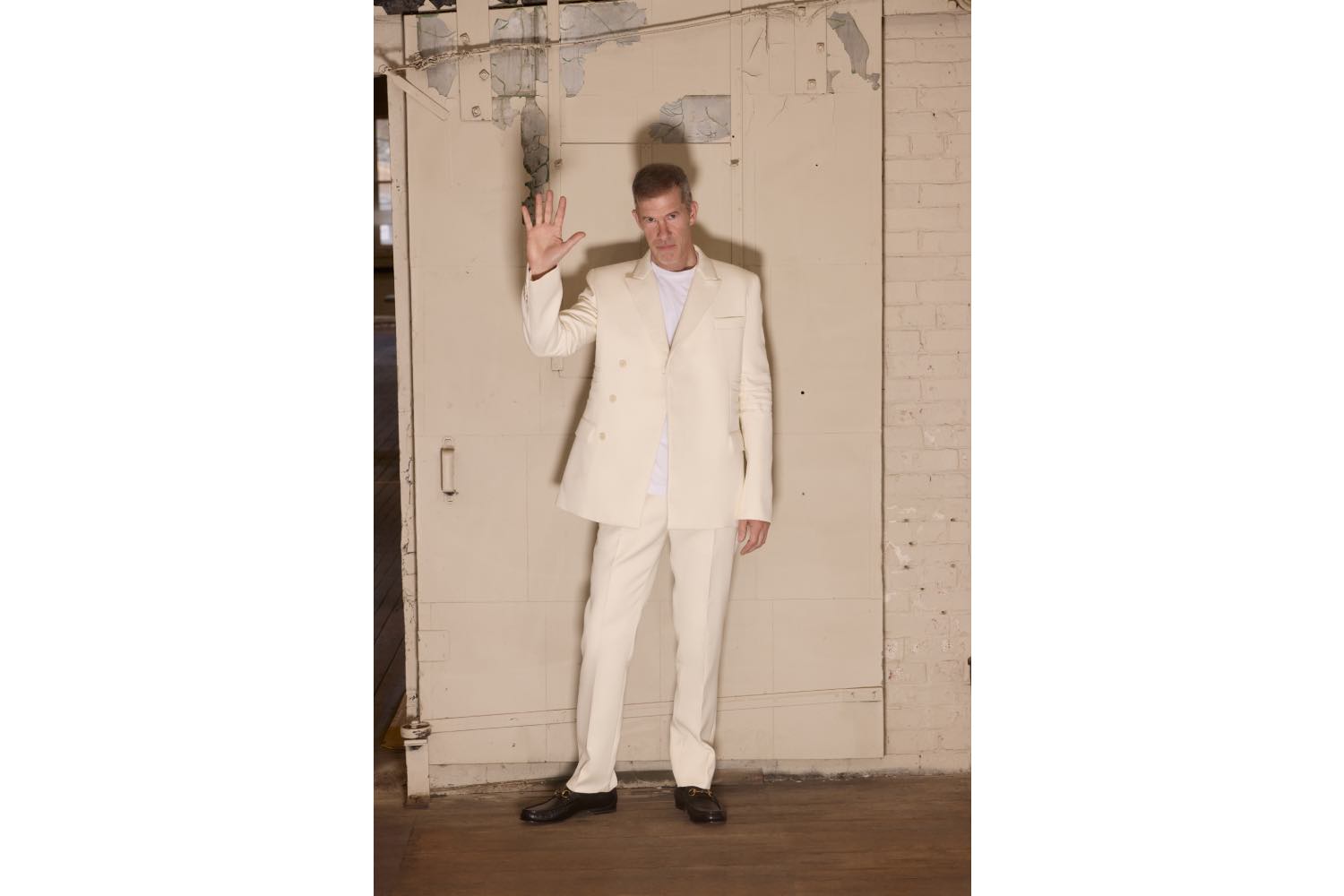

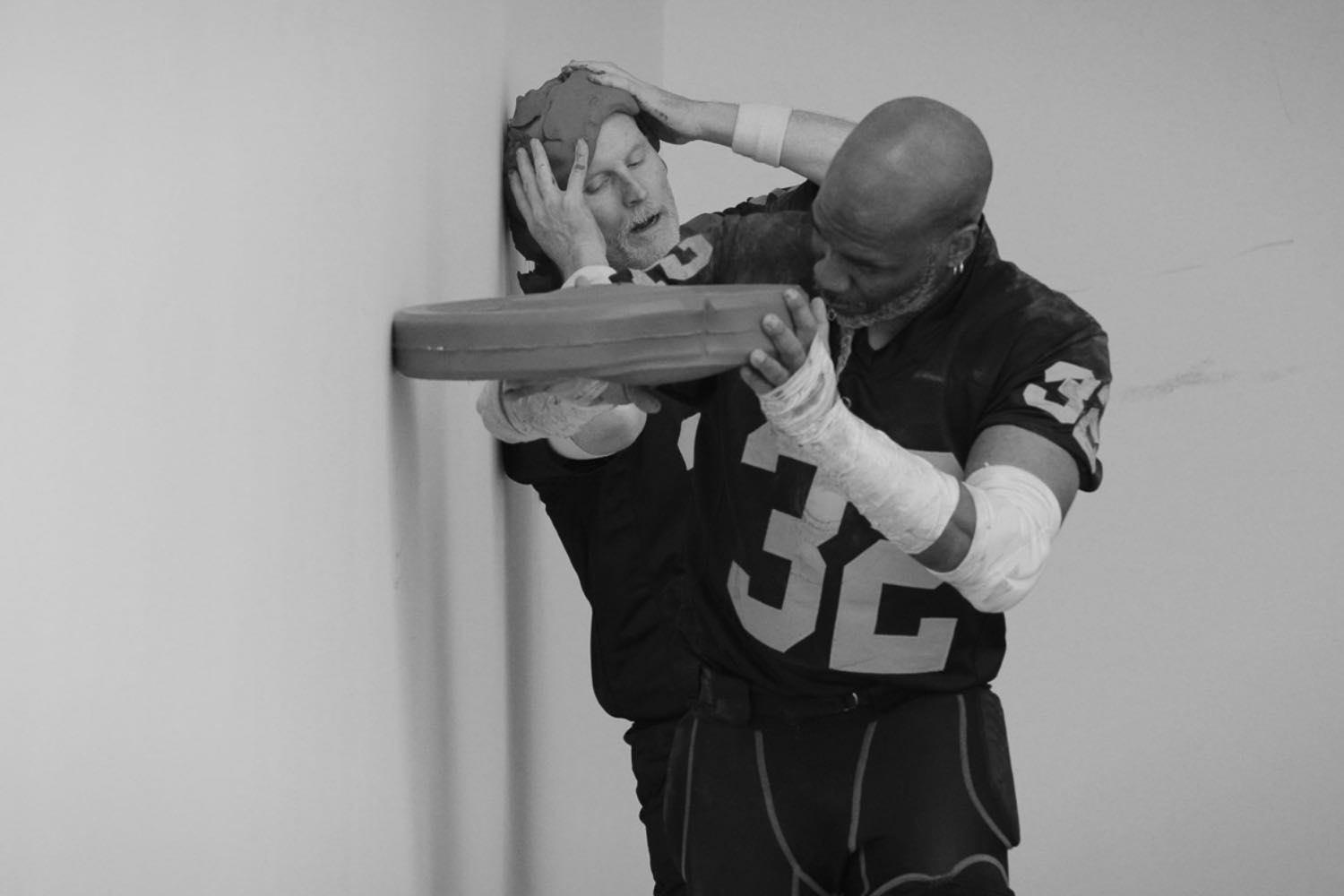

TB: I was drawn to artists who understand and gravitate towards this idea of the documentation of their work, and the archival flow of a work’s afterlife. The idea to have performances occur in the space specifically in order to be documented for the book was also something that emerged out of my own bodily engagement with the whole process. I wanted to be physically present in this project in a way that I maybe haven’t been before this, with the exception of the project I did in the Breuer building in New Haven in 2017, which in some ways was also an impetus for this whole endeavor. I was always at a careful remove from my work, by design. And I can be very shy and self-conscious as well! But at this point in my life it felt like an interesting, and maybe even necessary, shift, to be seen physically in relation to the works installed in the rooms. When people visit, I am there always, shepherding them through the many narrative twists and turns, with my voice continually wafting through the place. It’s why I was open to being dressed and photographed for this magazine in fact, to allow that aspect of the project to play out here in these pages as well. This theater aspect.

GH: I’m so grateful to be part of this. When we first met, in 2016, we quickly discovered so many shared interests, resonances, art questions, a love of martinis! I was amazed because before we met, you were an artist that I followed and admired and didn’t imagine I would ever know in life. And now we are working on this project together — I’m about to bring a suite of my sculptures to the space and present a new lecture-performance called 1–2 pm (taking place from one to two pm, of course!) I wonder if you wouldn’t mind talking a bit about how you approach working with and mentoring a younger generation of artists, especially queer artists. From where I sit (I was a teenager in the late ’90s) it’s quite unique — so many artists get to your career level and seem to have no interest in the people from subsequent generations. I’ve been struck by your openness and generosity. Where is this coming from for you?

TB:I think it comes from multiple impulses. I’ve always enjoyed dialogues with artists older than myself, and there was opportunity for this in the art education I had. To get to socialize with the artists that I admired, and I liked that infinitely more than exclusively hanging within an age-based peer group. I have often found myself wanting to escape that insularity. And then, years passed, and I found myself being older than a lot of other people! Younger than some too, but the situation had shifted, and my place in it. I never wanted to teach full time, I grew up in an academic environment and I sort of ran from that, and while I have taught a lot, sporadically over the years, and find myself around groups of young artists off and on, I was drawn to creating other sorts of relationships with younger artists. I witnessed this with Dan Graham, his particular sensibility that led him to be genuinely curious about younger artists, and I think it made his work resonate across generations and connect with a younger audience. So maybe it’s about pleasure, and inspiration, and maybe it’s also some form of self-preservation. What I do know is that I’ve never been attracted to large swaths of art, or artists; many things leave me pretty indifferent. So, when I do connect with other artists, and that includes young artists, it’s specific and strong. I get a lot from it. And while it may be perceived as generous, that’s not exactly where it comes from for me, it is much more about my drive to connect, and to link my work to that of others, across time. I once wrote a brief piece for a group show that I curated that all circled around the idea — via Frank O’Hara and Vladimir Mayakovsky — of inter- or transgenerational crushes between artists, and of artworks completing other artworks over time and space, like some people complete each other’s sentences.

GH: When thinking about intergenerational artist relationships, I feel we often forget how much AIDS changed the artistic landscape in terms of who lived to continue to make work, to teach and mentor, to write art history… I acutely feel these gaps, because those people would have been my teachers and the work I would have been looking at as a young artist. You and I share a commitment to a certain formal reduction as a vital artistic language. Call it minimalism, post-minimalism, whatever — but it’s a conviction that less can be more, identity doesn’t need to be represented in content but can be embodied in form, and that there is a politics to slowness, stillness, monochromaticity, repetition, and specificity.

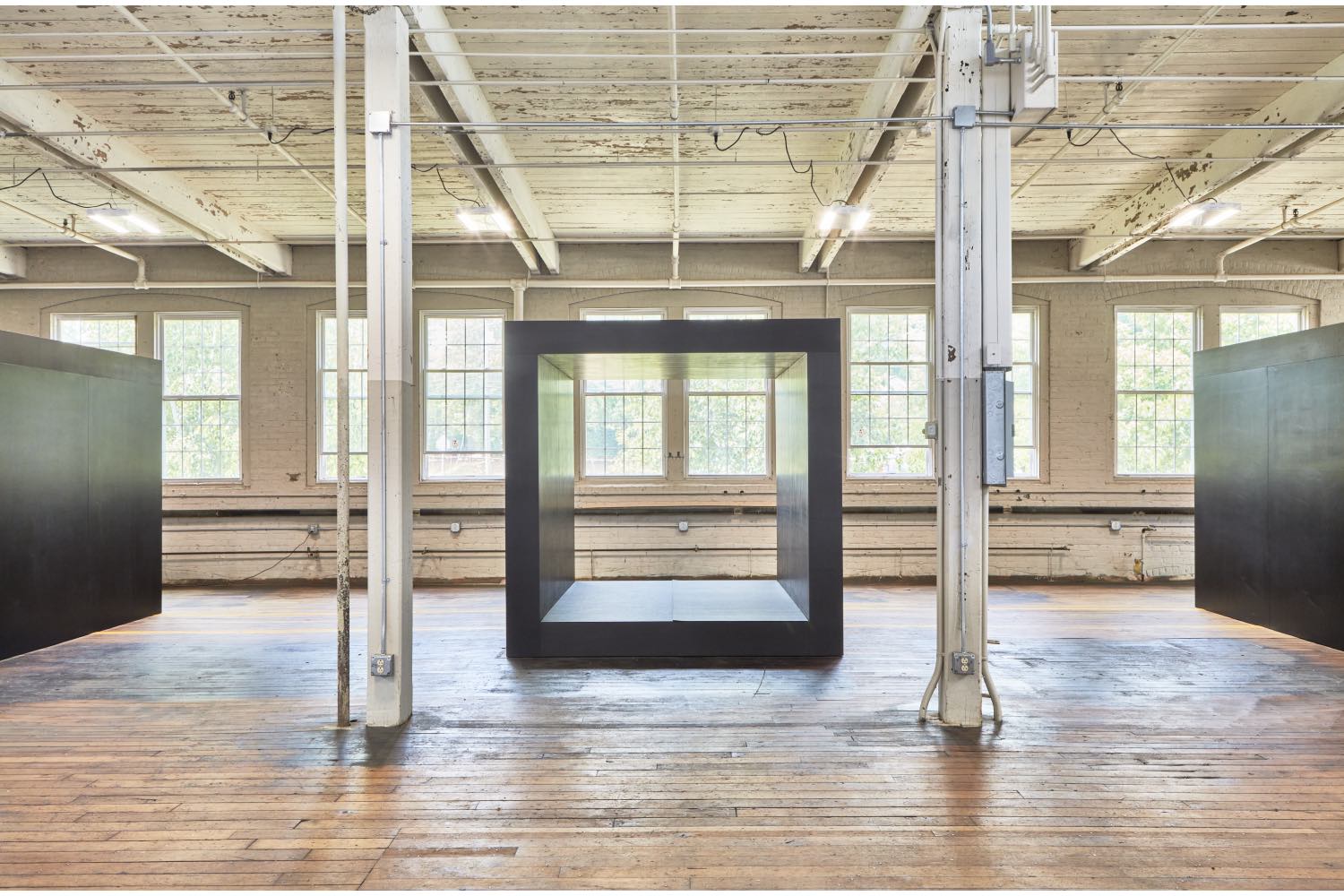

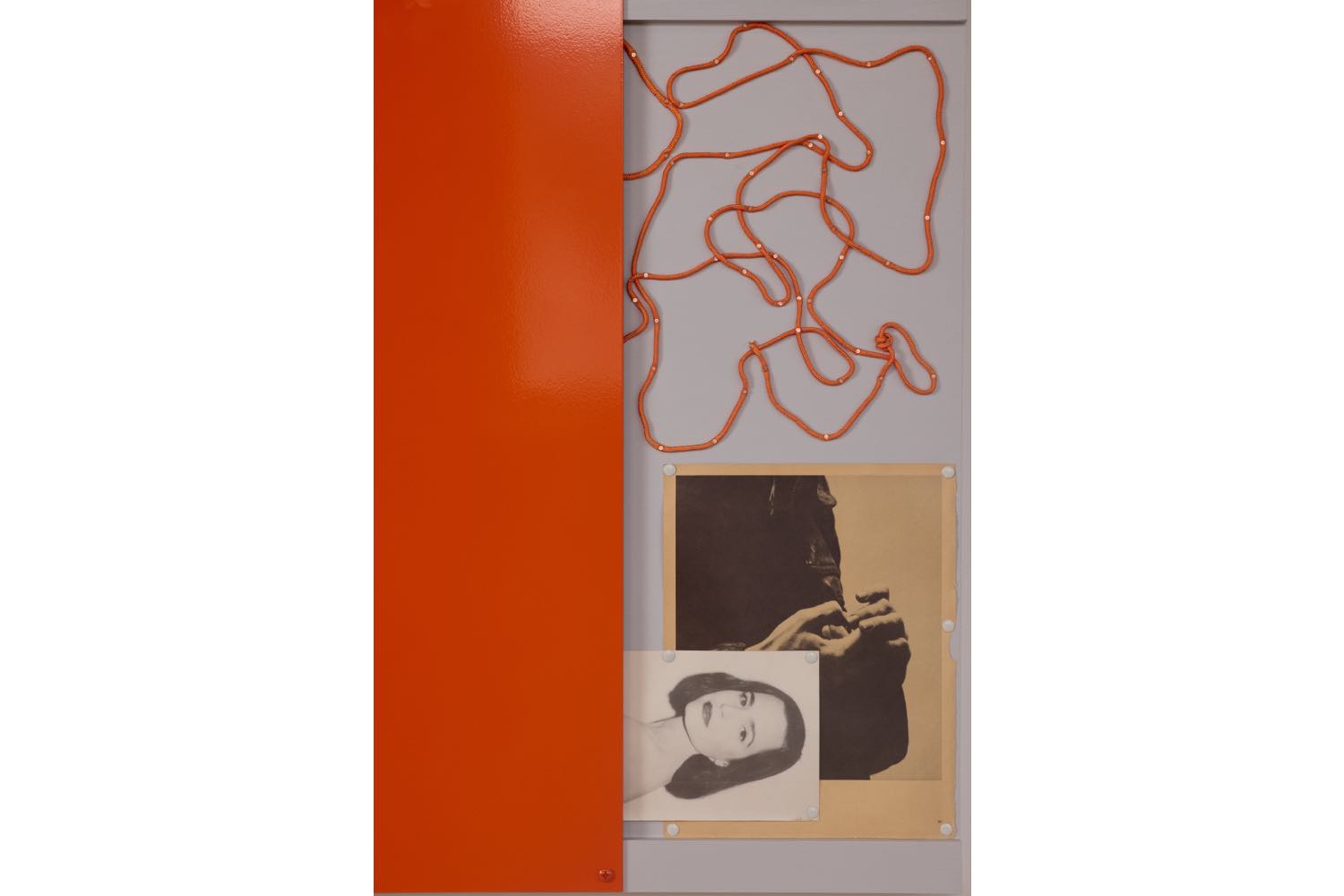

TB: Gordon, this makes me think in a number of directions at once. In Torrington, I reinstalled a large work from 2001, called Container 1, 2, 3. This work had been dismantled shortly after it was commissioned by an institution in Berlin, nGbK. I wanted to experience this work again. I mourned its dismantling, and its disappearance. Which is interesting because the exhibition it was in was called “Broken Partnerships,” which presented the work of three artist couples, one who had died an AIDS-related death, the other who had survived. Container 1, 2, 3 was created specifically for the exhibition, and it was meant to frame and be framed by the work of Ull Hohn, my boyfriend from those years, who died in 1995. In Torrington I’ve selected works of Ull’s to hang in the space around the three containers again, evoking both the original installation and our relationship, our work and our personal connection entwined.

GH:This sounds so beautiful. So much emphasis is placed on individual artists and artworks, yet equally valuable are the conversations between artists, and the way works speak to each other spatially in exhibitions, collapsing disparate time periods into one place.

TB: It makes me think of Felix’s work, and his role in my early life as an artist. A few years ago, I had the opportunity to see our works coupled in an extraordinary instance at Des Moines Art Center, where Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s “Untitled” (Water) (1995) and my Deep Purple (2000) sort of danced together in this very physical and highly chromatic way through the brutalist I. M. Pei-designed pavilion of the museum. It evoked so much for me, personal memories and details of course, but also the ability of work to engage subjectivity, identity, intimacy, through the expressive artistic language you are referring to, that has very little to do with traditional figuration.

And finally, it makes me think of your work that engages with Scott Burton’s various gestures, where you are engaged in a conversation with him and his work across time and absence. This form of affectionate, even passionate, embeddedness with another artist’s work and persona feels like a way to counter the very cold and difficult business of death, and in particular the artists we lost to AIDS who formed our multi-generational family structure. I see it as a meaningful political act of memory and perpetuity. I’m particularly attracted to the theme of waiting that you’ve taken up in relation to both your own and Burton’s work. I feel like there’s something, even in just this very word, that summons so much of what I find compelling about particular sculptural work and its relationship to various notions of duration and space. As long as there is waiting, then there is waiting for, and there are other subject positions and conditions to consider, and the idea of a fixed autonomous object and a fixed autonomous identity is rattled and shaken and called into question.

GH: In 1–2 pm, I was able to locate the generative potential of waiting as a form of “critical passivity,” as a site of the pleasures and pains of interdependence. Burton articulated this through his sculptures and performances when he described, in the 1980s, his ideal audience as “people waiting for people.” For me, waiting has become both a method and object of inquiry that has turned out to be incredibly generative in all the ways you name — relating to art making, vulnerability, risk, contemplative awareness, and an erotics of receptiveness to people, objects, and places.