The draw of nonfiction filmmaking often lies in its indexical quality — not only its ability to capture real people, places, and events, but also to create a world that, to a great extent, feels knowable. Peng Zuqiang, however, goes against this grain. His short films and installations, though rooted in the real and often drawn from his own life or history, often feel like fluid, compact capsules taken out of broader, more open-ended narratives. For instance, in his early documentary feature Nan (2016), he spent two years closely observing his own family, establishing the intensely personal tone that marks his style. In contrast, his recent installation Déjà vu (2022–23), currently on view at Emalin in London, captures the fleeting quality of time and perception, and the elusiveness of any categorization, while touching on themes such as visibility, empathy, and solidarity across class, race, and gender. His art thrives in the fissures and gaps of how we think, know, and relate to the world — and to each other — while attuned to things unsaid or unseen.

For his black-and-white short Sight Leak (2022), shot in 16mm and Super8, Peng took inspiration from Roland Barthes’s posthumously published Travels in China (2010). In this diary, the French philosopher detailed his 1974 trip to China during the Cultural Revolution as part of a delegation from the French literary review Tel Quel. Critics James Wood and Dora Zhang have described Barthes’s text as a study in frustration: he and his co-travelers went on an official tour, and their ability to observe or have spontaneous interactions with the Chinese was curtailed by censors.1 Barthes chronicled his inability to connect with the landscape, people, and culture, and yet despite being aware of his own interpretative limitations and cultural biases, his judgments were often dismissive.

Peng isn’t interested in critiquing the Frenchman’s cultural insensitivity. Instead, he highlights the textural instances when a certain erotic charge emerges in Barthes’s prose, breaking through his ennui. A sexual desire that seeks and awakens one’s senses embodies a foreign homoerotic gaze. Yet, as Peng noted in an interview, it also offers an opening, or a “space to play with.”2

Peng engages with Barthes’s text by feeling around its edges. Sight Leak opens with a throbbing night scene in Peng’s home city in China, Changsha, where he shot the entire film with friends. Onstage at a nightclub, mostly young men dance to a song by the South Korean band Girl’s Group. The scene is murky; strobe lights briefly illuminate gyrating bodies and the crowd on the dance floor before the scene dissolves into obscurity. The film then unfolds through a series of quick glimpses: daylight leisure time at a riverbank, where a man and a dog go for a solitary swim, and sequences of Peng following his friends as they wander through Changsha, crossing streets, cafes, and parks.

Other moments in the film, such as a close-up of a man picking at a mosquito bite on his calf, or a nocturnal scene in which another man pulses with his fingers languidly as a storm thunders, feel like images of what might have been. These are visions of male bodies, not sexualized but portrayed as tender and vulnerable. In one scene, Peng’s friend strikes playful poses while water gushes across a pond in the background – an image of exuberance and spontaneous release that eluded Barthes. Unlike the French philosopher-cum-Sinophile flaneur, Peng recaptures the jouissance of an idle Chinese wanderer, a sense of freedom that Barthes could not experience walking and observing in a distant, distinct context.

A few select lines from Barthes’s text, read in voiceover by Peng, appear early in the film during the riverbank scene. One audio fragment recalls a fleeting, electric encounter with a young man: “I felt his hands soft and long, and a little bit warm.” Here, Peng lingers on the image of water and the silhouette of male swimmers before introducing shots of other men stretching on the pier, paddle-boating, and fishing. As the camera briefly shakes, the image becomes disoriented. This formal disruption suggests that Peng is also interested in the fleeting quality of the erotic flash described by Barthes. Such fugacity becomes Peng’s theme and method, as he makes viewers aware of having to glean images and their meaning quickly, piecing together bits of visual and textural information without much introduction. This form of tactile knowing – unstable yet open, apprehended in flight – clearly interests Peng, at least in part, because it pushes past preconceived judgments and ideas.

The questioning of preconceived notions comes to the fore in the film’s latter part, as Peng follows friends who respond directly to Barthes’s diary. “Perhaps gazing is less about what I am projecting but more about what the other sees in my eyes,” says one friend, in a striking reversal of Barthes’s one-directional gaze that shifts the agency from the observer to the observed. Another male friend recounts his experience of living in a factory dormitory with many other men, where he often felt conscious of being watched. Through these moments, Peng introduces the idea of an imbalance of power, reminding viewers that bodily contact raises questions: who has the right to touch whom, and how does power manifest or shift in these exchanges?

The film camera and the filmmaker are by no means exempt from the power dynamic. The young men filmed by Peng — albeit all his friends — repeatedly gaze back at his camera, as if to underline their awareness of his looking at them. But Peng also voices some doubt about how deeply a gaze affects the other, allowing for lightness, and play. For instance, when one young man jokes in the voiceover: “You are totally overthinking, maybe you’re exaggerating, maybe they are not looking at you at all.”

This granular attention to interpersonal dynamics is characteristic of Peng. While shooting his first feature, Nan (2019), in his family home, Peng observed his disabled uncle under the care of his mother. He noted that “certain family fights that may look dramatic are, in fact, a form of communication and love.”3 This observation was born out by Peng patiently following his family’s daily routines. It also set the tone for all of his work, so often underpinned by subtle permutations of care, apathy, or aggression.

This kind of oppositional tug also underscores Peng’s keep in touch (2021), a piece combining HD video and Super8, conceived as a five-channel video installation. Created during an artist’s residency, the film revolves around gestures and objects, hewing closely to the filmmaker’s personal, diaristic mode of working with family and, in this case, his LGBTQ+ artist friends. The actions include a friend adroitly spinning a pen, another applying Tiger Balm to her limbs, and a scene where Peng and his partner clip their nails.

The frisson in keep in touch arises from Peng’s exploration of solidarity — a concept he found compelling, yet sometimes felt had become an empty slogan. “Can we share a future when we have such a different historical past?” Peng asks in the voiceover. Yet the film’s clear sense of a shared space and gestural connection suggests that the body can be a guide and conduit. Even if it is not supracultural, subject to ideologies and economic and political circumstances, its capacity to reach and touch the other, favoring senses over intellect, makes Peng’s answer to the question seem affirmative.

A similar sense of gauged optimism arises in Peng’s short film The Cyan Garden (2022), which reflects his fascination with historical narratives and his simultaneous reluctance to use archival material. The film briefly recounts the history of an underground communist radio station near Changsha, called Voice of the Malayan Revolution, which broadcast from 1969 to 1981. There is no archival footage here; the images viewers see are primarily of Peng’s friend who works at a nearby resort. In one key thread, a young man tells in the voiceover the story of his aunt and uncle, who, as members of the station, were forbidden intimacy but nevertheless fell in love.

Themes of empathy and tenacity against the odds permeate Peng’s entire filmography. Perhaps not surprisingly, he directs his gaze to how the past can be felt in the present, with an eye to current developments in China. Both keep in touch and The Cyan Garden resonate with Peng’s reflections on solidarity among young people in China during and after COVID-19, particularly in the wake of anti-government protests met with police violence.

Violence becomes the central theme of Peng’s mixed-media installation Déjà vu (2022–23), combining 16mm footage, digital sound, 3D clay, and iron oxide, which is currently part of “Evidence,” a two-person show with artist Aslam Goisum at Emalin, London.4 As Peng explained to me in 2022, he found himself meeting with Chinese filmmakers online, discussing how image makers could respond to the proliferation of violent images online, which were emerging in China and abroad in the wake of the pandemic. “I just couldn’t pick up the camera,” Peng told me, “so I found myself drawn to other, cameraless forms of making images.”5

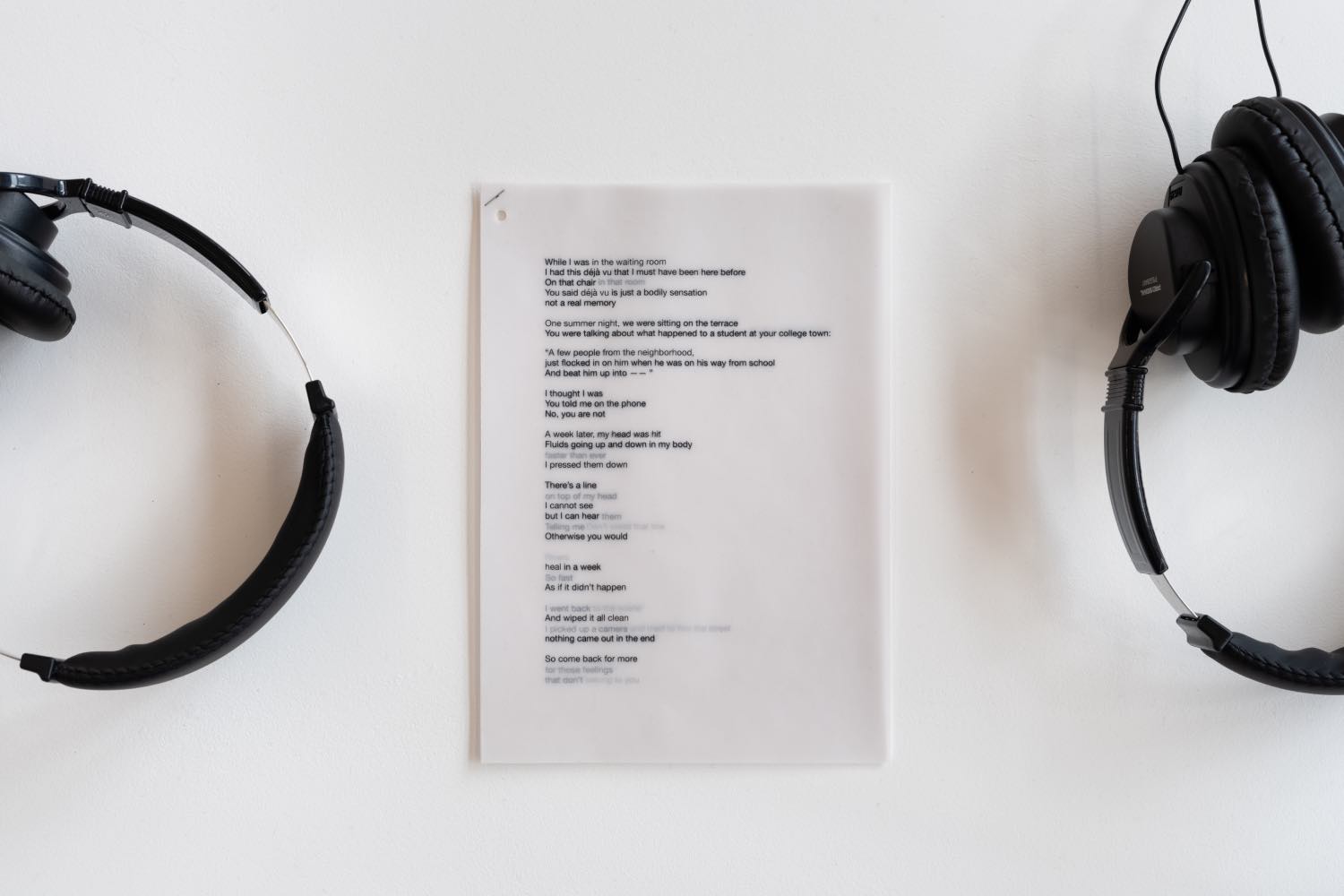

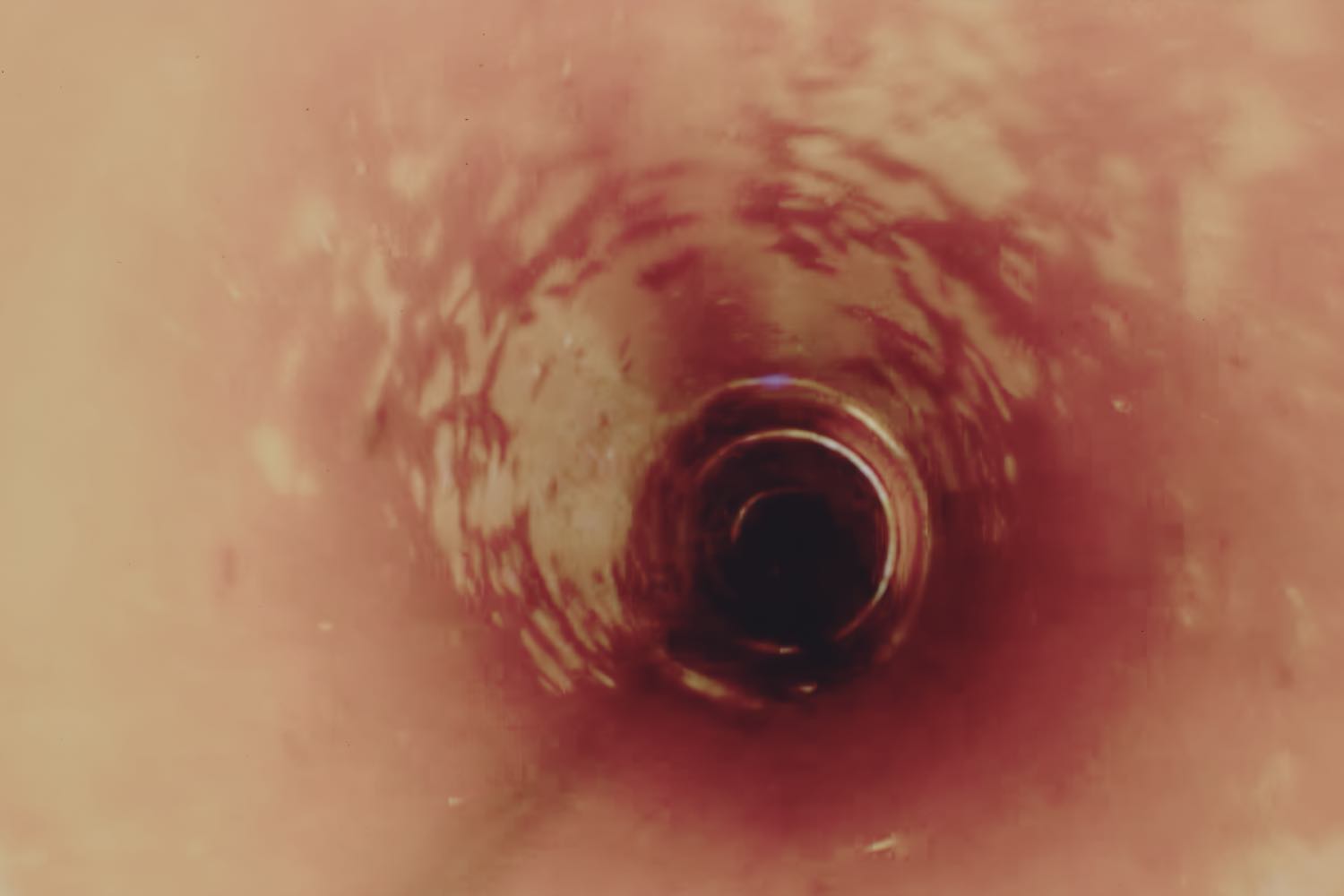

The only image in Déjà vu6 is a photogram of a wire cable – an object sold in China as an “escape tool” for fires. In the film, the wire becomes a constantly pulsing black band against a white background. Peng evokes the tragic event by also showing the film against a window. Meanwhile, most of the violence plays out in the viewer’s mind, as Peng introduces an audio recording that collates recollections of two distinct violent episodes: the filmmaker injuring his head, and a young man brutally beaten in the wake of COVID, in an ethnically motivated hate crime.

Peng returns to the metaphor of a crack in a sculptural clay piece that is part of the installation. The object is inspired by Chinese antique brush holders – particularly one antique piece sculpted in the form of a young male body, which Peng recreated, first with a 3D printer and then with his hands, deliberately leaving visible cracks and fissures.

This metaphor extends further. In the installation’s audio, the syntax breaks; words are cut off repeatedly. As language fails, any coherence that viewers might glimpse is necessarily partial, not unlike the sideways gaze to which Barthes refers in his diary. Violence seeps in between the cracks. It seems to tear both a sense of time — as image and sound play on a loop in staggered snippets — and our ability to understand it. Yet it is here, in this volatile space, that the subject must be found. The film beautifully captures this attempt at grasping for empathy. Words gain deeper resonance through repetition; fragments alliterate and sharpen. Reality doesn’t coalesce, but there is a unique power in utterance, in being heard.

Whatever the limitations — of recall, language, understanding, or solidarity — that viewers confront as they watch Peng’s Déjà vu, these limits poignantly echo the failures of solidarity but also the brief, fleeting instances of curiosity, openness, connection, and care that Peng captured in Sight Leak and in keep in touch. In this sense, his commitment to finding granularity in embodied experiences, both queer and non-queer, reveals the complexity of grappling with boundaries, both physical and symbolic.