Candice Breitz says she hasn’t slept all week. Yet, as I visit the artist in her studio in a long-gentrified part of Berlin’s Mitte district, she’s awake and articulate. Right now, she’s working on a new series of works titled Labour, for which she’s on call to film babies being born (not her own). She is preparing for multiple exhibitions. On social media, she’s been commenting vigorously on a series of threads calling out the lack of women and artists of color in a group exhibition premised on Afrofuturism at Berlin’s Künstlerhaus Bethanien.

There’s a lot to her, and a lot to her body of work. Before our meeting, I’d again failed to view the entirety of Love Story (2016), the first chapter of what the South Africa–born, Berlin-based artist — who has primarily worked in video since the late 1990s — calls a trilogy. The footage in Love Story amounts to approximately twenty hours of viewing time. TLDR (2017) is part two of the trilogy; the final chapter is a work in progress and not yet to be discussed. Both completed pieces deeply question how we consume information, interpret images, and perceive representation in a high-stakes attention economy. They ask where we choose to direct our attention, what it means to empathize with the otherwise voiceless, and, as so many of Breitz’s works do, question the ubiquity of white privilege.

On view in the South African Pavilion during the Venice Biennale in 2017 — and elsewhere since — Love Story opens with a seventy-three-minute filmic montage in which actors Alec Baldwin and Julianne Moore perform fragments from the personal stories of six refugees. The texts are presented in first person; the actors sit unadorned in front of a green screen. It’s briskly edited, suggesting a conversation between the two stars. In a second space are six interviews, mostly longer than three hours and each displayed on its own monitor, with the actual refugees whose narratives Moore and Baldwin channel, now interviewed within similar green-screen settings. They have fled countries like Syria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and India; two have been granted (or are seeking) asylum in Berlin, two in New York, and two in Cape Town. Three identify as women, three as men. All share complex explanations of their life situations, admissions, and emotions not easily reducible to a news story, pithy quote, headline, or even an hour’s conversation. The actors’ script, in turn, distills and manipulates this source material. Using the celebrities as “bait” (as the artist puts it), the piece urges viewers to consider how we pay attention to stories differently, depending on who is telling them.

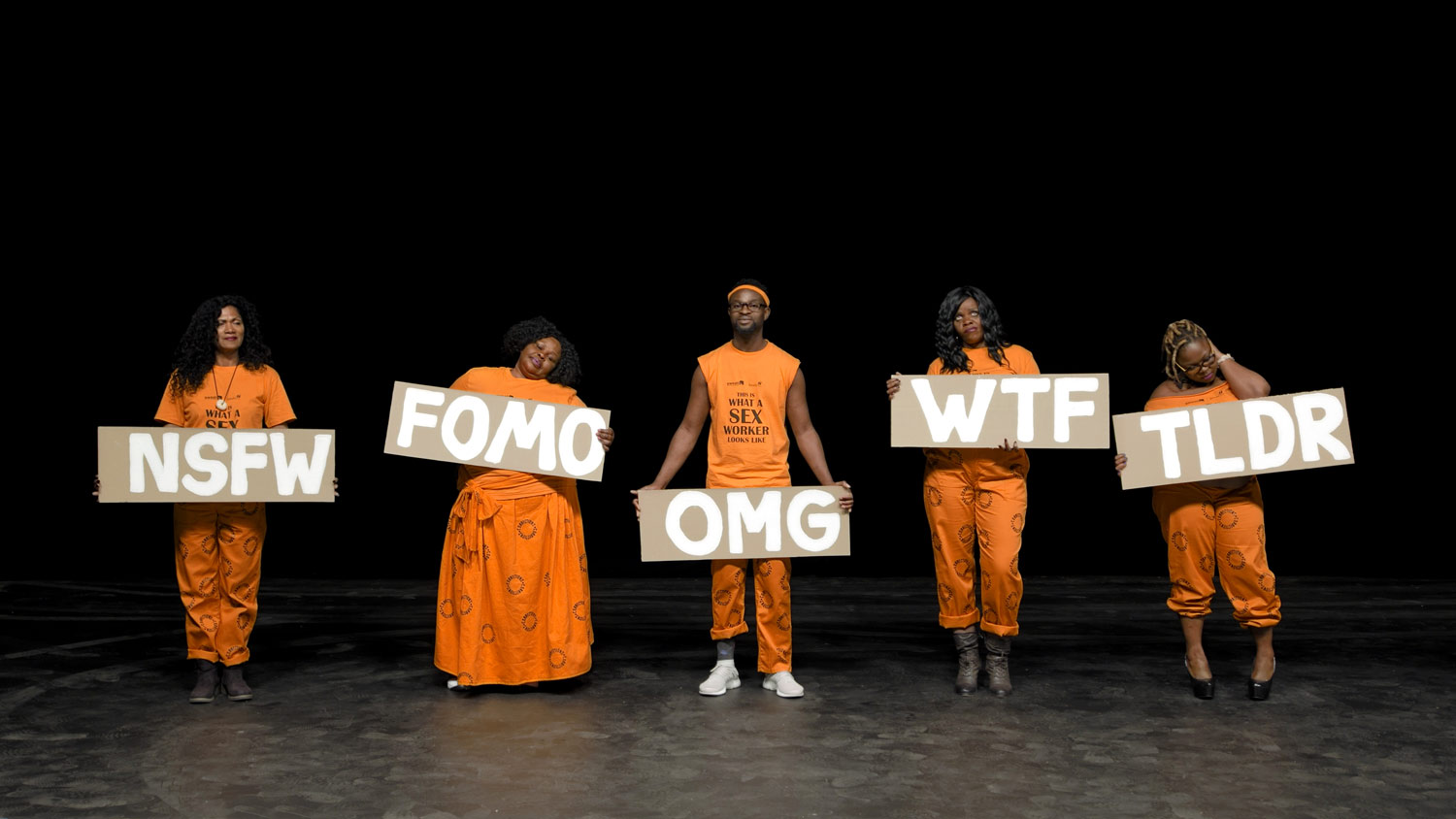

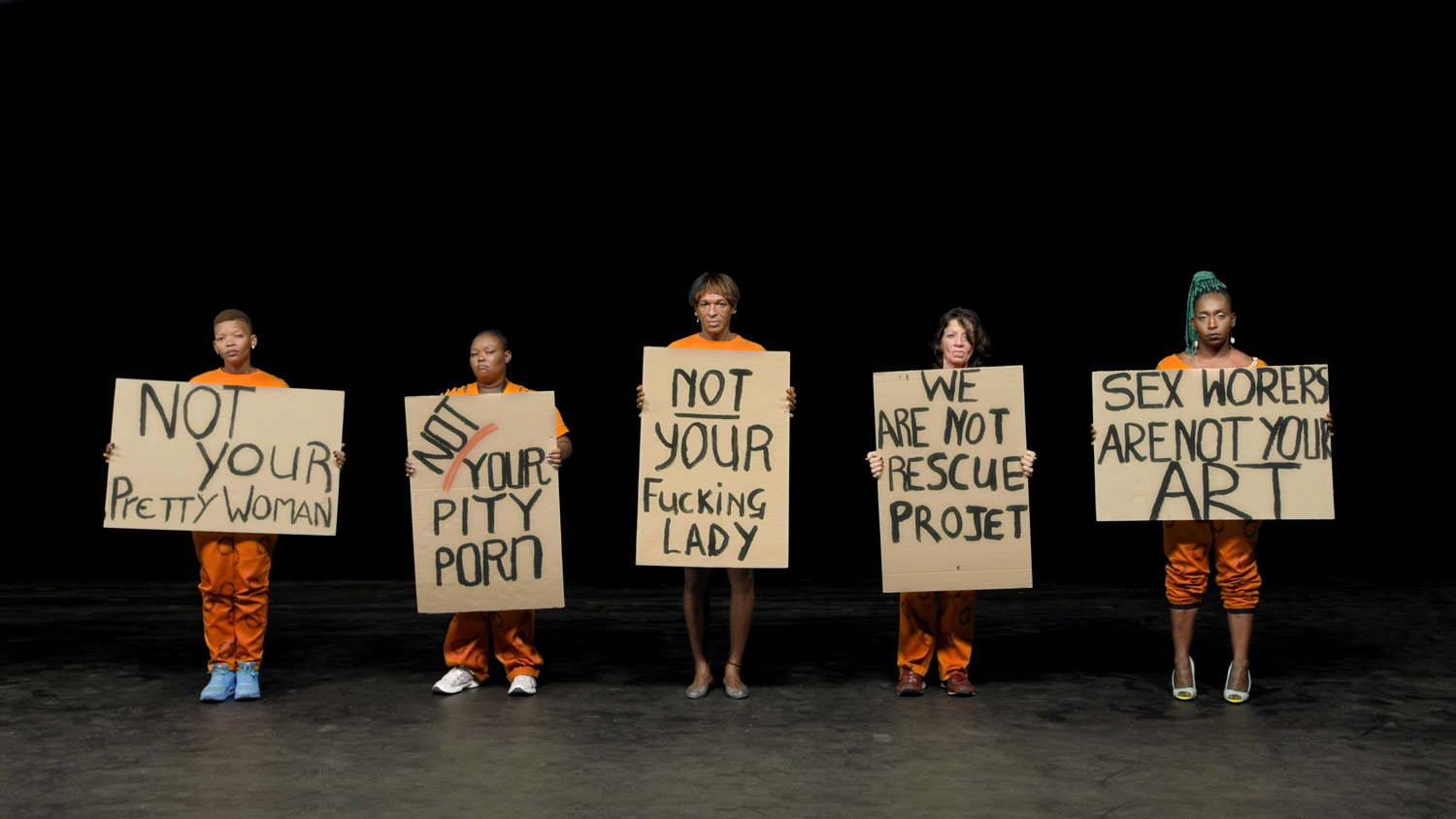

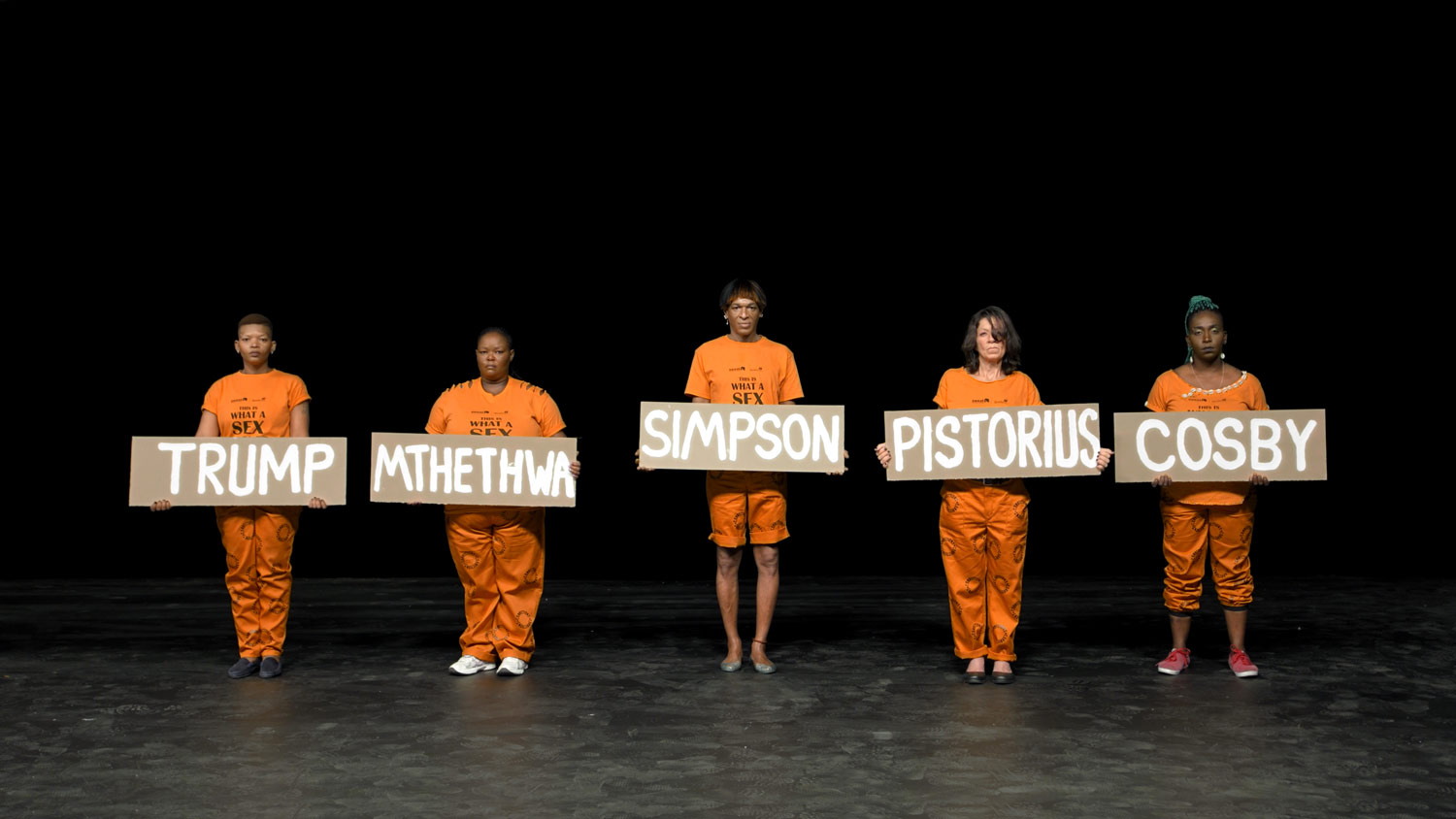

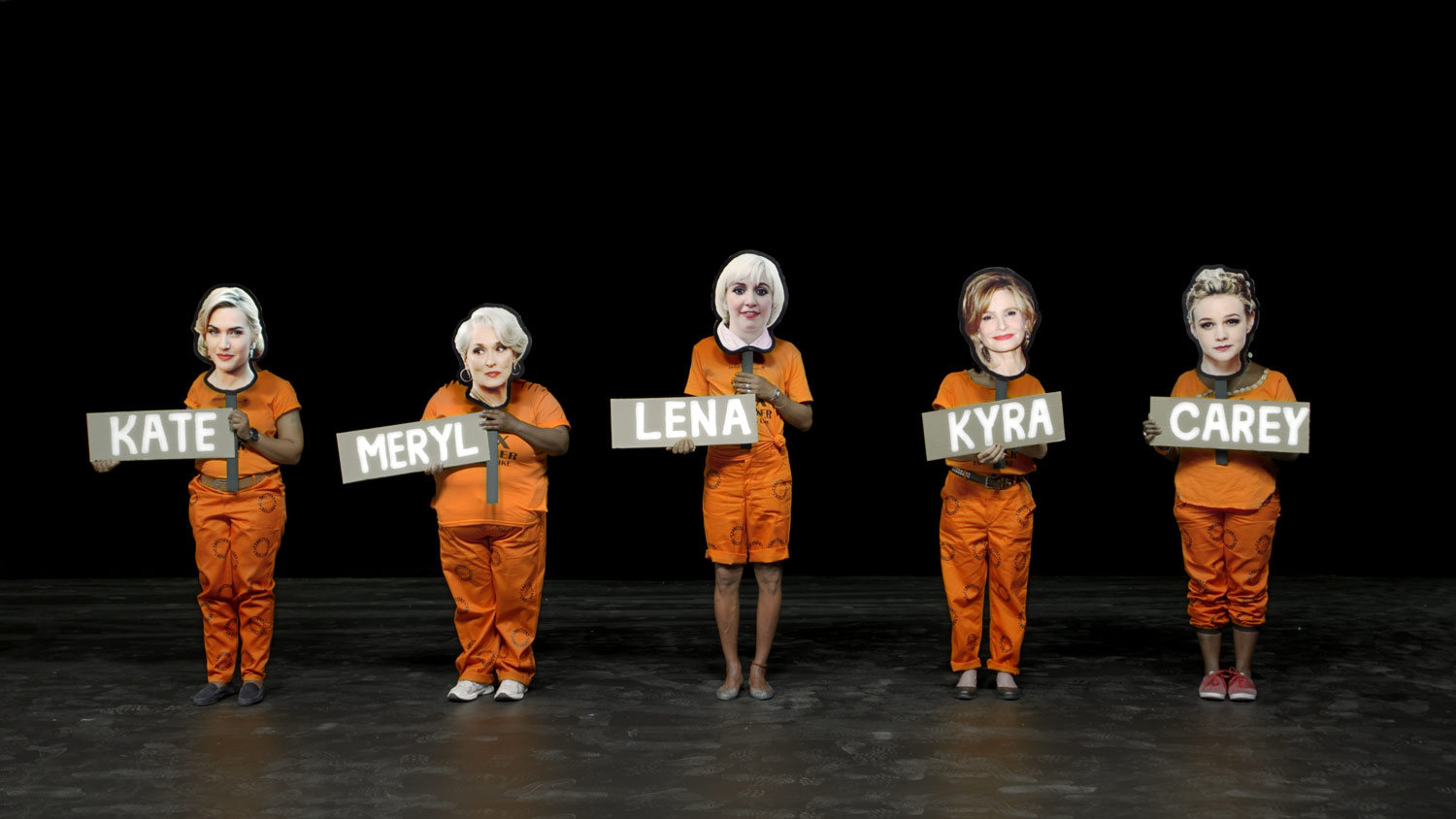

During a stretch of volunteering at Berlin’s refugee registration center (which was dismally understaffed) over the summer of 2015, Breitz found herself in a series of casual conversations with a range of refugees she met waiting there. “I began reflecting on the wide gap between the specificity of what I was hearing from individuals, versus the translation of that human material into statistics, alarmist headlines, and generalizations in the mainstream press,” she says, explaining her subsequent decision to conduct long interviews with six asylum seekers for Love Story. TLDR (social-media speak for “too long, didn’t read”), on the other hand, creates a platform for the personal narratives of a community of sex workers who are affiliated with a Cape Town activist organization called SWEAT (the Sex Workers Education & Advocacy Taskforce). The work’s title registers the unlikelihood that viewers will watch the piece in its entirety. Lengthy interviews with ten of the sex work activists are on view in a room that Breitz refers to as the “archival core” of TLDR, but the work’s attention-drawing centerpiece is scripted and choreographed: a musical drama narrated by twelve-year-old Xanny Stevens within an eleven-meter-wide installation consisting of three projections. In prison-garb orange against a darkened set, the community of sex workers appears as a life-size Greek chorus, bearing cardboard protest signs adorned with slogans from their lives as activists (“NOT YOUR PITY PORN,” “SEX WORKERS ARE NOT YOUR ART”), emoji “masks,” the names of female Hollywood actresses who signed a petition against the decriminalization of sex work, as well as those of celebrity sex offenders (Breitz started shooting the piece the day the Harvey Weinstein story broke). All of these elements come from pop or protest culture and reveal the violence, assumptions, and prejudices global sex workers face, but they also highlight their humanity and political agency.

Breitz seems to be forging into new territory. Her work has always explored the machinery of identity (in the Factum series, dated 2010, identical twins discuss individuality and other topics in dual-channel installations), the ominous power of celebrity culture, and gender stereotypes, usually via media tropes and from a certain somewhat abstracted distance: Her, 1978–2008, for example, sees close-ups of Meryl Streep characters drawn from twenty-eight films silhouetted against black backgrounds and cut into ultra-brief vignettes that cycle through experiences of womanhood such as marriage and motherhood, intercut with wordless and objectless gestures and glances. Breitz’s work has also zoomed in on representations of suppression and control: I know you think I’m crazy, but I’m not, I’m not! (1938–2019), from Breitz’s series Digest, seals a series of video cassettes in black acrylic paint, displaying them as painted objects revealing just one powerful verb each, such as “abduct,” “riot” or “resist.” But since 2015, her work has become increasingly attuned to the fast pace of societal change and political upheaval, and is increasingly direct, even explicit, in its modes of production and representation.

Art’s documentary turn, especially in light of representing social issues, has been broadly discussed for at least two decades by writers including Hal Foster and Mark Nash (connecting to the philosophical writings of post-structuralists like Baudrillard, Lacan, and Rancière). But was there ever a clear line between “reality” and “fiction”? Curator Tanya Barson claimed that “the traditional dichotomy between art and documentary can be considered a false dichotomy,”1 meaning the documentary form in cinema or journalism and the documentary impulse in art, especially post-1990, were never delineated (note: another artist who addressed the refugee crisis, Ai Weiwei, follows a conventional cinematic documentary format in Human Flow, 2017). Having Baldwin and Moore reenact refugee stories clearly amounts to interpretive performance, but as interesting as it is to be provided with source materials, Breitz’s interviews are already themselves a representation of reality, a regaling in a controlled environment that resonates with and reveals the agendas of both the interviewer (Breitz herself) and the six refugee interviewees.

I initially read Love Story too simply, as a media critique (beyond writing on art, I sometimes work as a newspaper journalist. During the height of the refugee influx, I reported from Austrian refugee camps and transit nodes). I recognized Breitz’s pre-edit process as nearly identical to my own: conducting long research interviews, then tweaking out details to create a narrative, all the while aware that interviewees are self-selecting but also experiencing the discomfort of being instrumentalized, or, as Breitz puts it, “having value extracted from” their life stories from the vantage point of privilege. Yet I felt a twinge of envy that Breitz has the liberty to employ devices like famous actors, green-screen production teams, source material, and especially time and space to reveal the contradictions inherent in collecting and communicating narratives.2 In both completed chapters of Breitz’s ongoing trilogy, the complexity — if not exactly the reality — that she rightly sees as absent in our media-saturated world is there for the taking, if only audiences are willing to invest the time to take it.

Do they? Certainly not every visitor will view the full seventy-three minutes of celebrated white actors delivering digestible, edited narratives in neutral American English before a uniform backdrop; let alone the long documentary interviews with the refugees or sex work activists. The footage of the interviewees, like certain news photos, may well evoke empathy, but as Breitz herself points out, empathy is not enough; just feeling what one is “supposed” to feel may prevent reflection on the social and political circumstances that extend visibility and resources to some, while making such privileges utterly remote to others: “At the core of these works is an effort to make visible the workings of the attention economy that we inhabit,” says Breitz. “I think of Love Story as a machine that suspends viewers between the opposite extremes of the attention economy. To experience the piece, you literally circulate between two versions of the same set of narratives. You’re suspended between the hypervisibility of the Hollywood actors (in their sanitized re-performance of first-person interviews) and the relatively stark delivery of the same stories by those whose lived experience they record, individuals who are seldom granted the opportunity to be heard. Ultimately, you’re left to negotiate a position between two contrasting experiences, which inevitably means making decisions about where you will invest your attention.” It’s a stark reminder of decisions we make while ceaselessly navigating the sea of information that is meant to alarm, influence, exploit or, perhaps most of all, to simply entertain and distract.

***

As Breitz’s art has come to more overtly address current political conundrums, so has what she refers to as her extended practice. She uses Facebook to comment on gross inequalities and blind spots that are symptomatic of patriarchy and white supremacy. She has been supportive, most recently, of the anonymous intersectional feminist group SOUP DU JOUR, which became active in late 2018. The collective has launched campaigns to highlight the egregious marginalization of women and artists of color from various exhibitions and art events in Germany and beyond. SOUP DU JOUR chooses anonymity to prevent those activists who live precariously in the art community from exposure to institutional punishment or exclusion. Breitz is outspoken in amplifying the collective’s campaigns, noting that she is one of the fortunate few who can afford to take such risks: “If one cares about a given political urgency, one has to move beyond acting as an artist. It would be naïve not to acknowledge the limitations of addressing the political from within art practice or art institutions.”

The dialectic between artist and citizen is clear to Breitz, even if the line between the two is increasingly muddled: TLDR, in fact, asks whether art can be a vehicle for activism, whether a privileged artist can adequately and meaningfully represent marginalized communities without giving pat answers. But perhaps art and its elitist system must take on more than they have, insofar as they can. In her work, Breitz seems to be crossing medial borders — without a passport, so to speak — in response to local and global events. She offers hours of dense material to offset the effects of the single press images that outrage but then quickly disappear. She exposes the manipulation inherent in contemporary image distribution. And she offers the subaltern a platform alongside, or through, prominent people, with all the contradictions that this might imply.

“We’re living through dark times right now, as a result of which some of us feel an increased urgency to be vocal,” she says. “Those of us who can afford to speak out — and we should never forget that being able to speak out is a privilege — are no longer willing to be complacent or remain silent. Many of us are moving out of our comfort zones and taking on small but meaningful acts of resistance in our daily lives, whether that means going onto the streets to attend protests, taking on teaching commitments, refusing to participate in exhibitions or other events that are designed to disproportionately platform white men, or finding opportunities via which to proactively support the practice of individuals who have been marginalized within the cultural mainstream.”

In art as in life, resistance is not futile.