For centuries, making art has meant opening windows where there are no walls; artworks are open windows “through which history can be contemplated,” as Alberti suggested. Every art object is a window: even if it is a sculpture or an opaque surface, when you look at it, you think you can see something other than its reality. Bianca Bondi’s art is both a radicalization and a critique of the Albertian model. First of all from a formal point of view: instead of abandoning the window, she radicalizes this model to such an extent that the world becomes its material content rather than some Other that we can never touch. As if its width were extended to materially include the entirety of the reality that it was supposed to make visible. As if its body and its power were intensified to make them coincide with the world. The vitrine, the technical apparatus that Bondi’s art systematically makes use of,is the result of this fusion between the window and the world, between the medium of representation and the object represented, between art and reality. Art must no longer be the sign or simulacrum of a world that exists beyond its body; on the contrary, it is the ambient world of reality, its living space, its ecosystem. As Bondi herself says, “The relationship of the work within a space is a symbiotic process.”

That’s why the thickening of the window and its metamorphosis into a vitrine is not a matter of simple aesthetic options. On the contrary, it is based on a vital necessity. If art must include the world it must blend with it, because it must push the life of things to their limits, rather than freeze them in some state just prior to their dissolution. In this sense, Bondi’s showcases are not mere scholarly variations of the iconographic theme of still life: they are the most radical reversal of it that can be imagined.

It is not even a question of explaining the transformations that take place in these spaces. Itis just a matter of bending the world so that protected spaces open up, so that things can change their nature. The vitrines are cosmic accelerators that capture portions of reality, intensifying its lifecycle. They are not instruments of representation: they are incubators of the world in which beings become free to metamorphose again according to a freedom that no technical formula can ever tame.

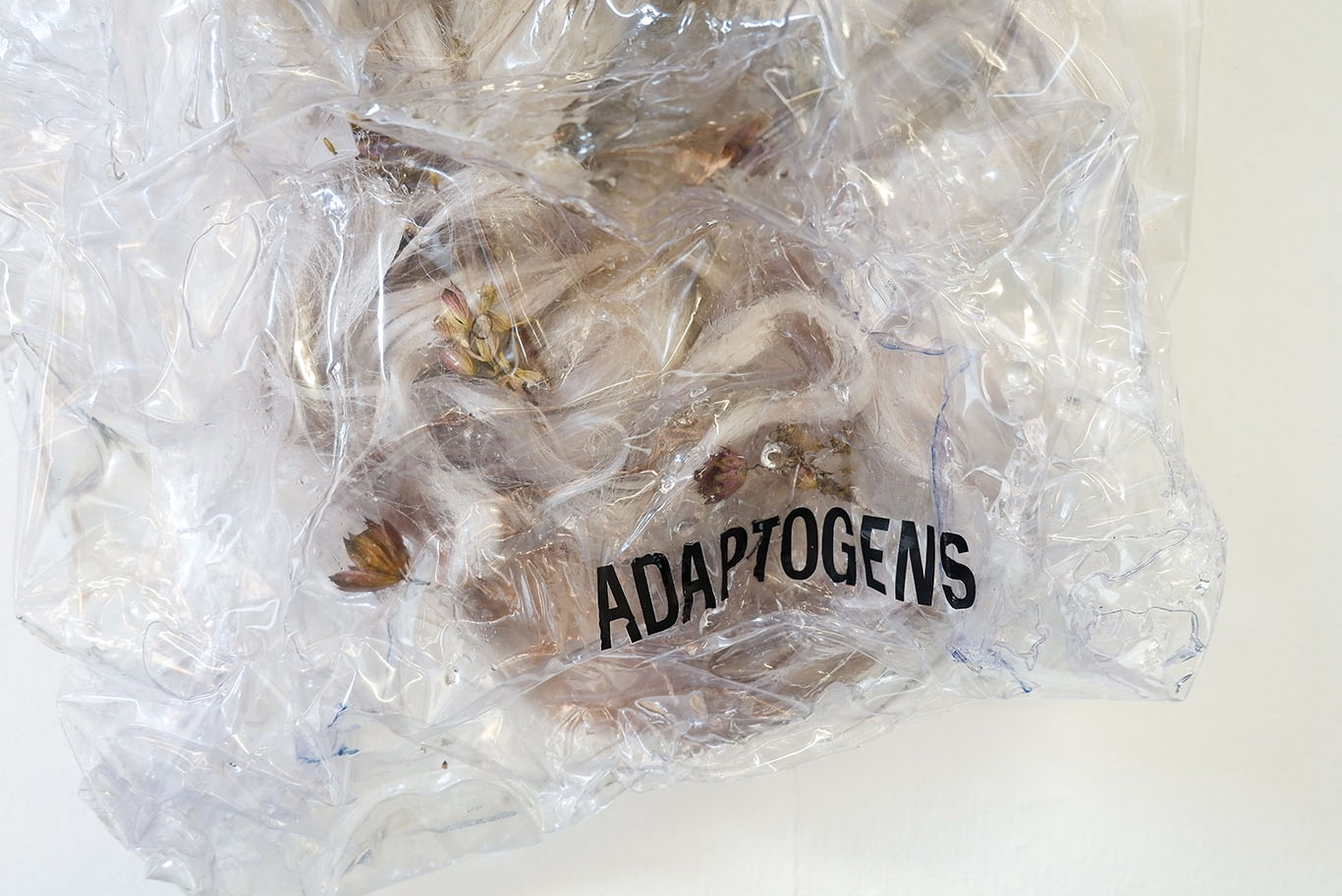

Art is an activity that aims to liberate the capability for metamorphosis inherent in each thing. That’s why it is much closer to the alchemy of digestion —thequintessential art of metamorphosis—than it is to vision; the vitrines are open-air cosmic digestion spaces, where the world reinvents itself at any given moment. They are translucent stomachs wherein the world invents its organic or inorganic future, or tries —as in plastic bags — to stop the transformation of some of its elements. To turn artworks into digestion chambers in the midst of the world’s matter also means transfiguring the very idea of digestion. Art, that most sublime and refined form of technique, must make it possible for the world to be digested by itself —to allow the cosmos to draw from itself, from its flesh and belly, the energy necessary to become what it is. Conversely, the relationship between artwork and world is no longer that of the exception. It is the same as the relationship between stomach and organism.

Furthermore, thanks to art and these incubating vitrines, everything will relate to everything else via the process of digestion. Far from being a shameful and unspeakable activity that every living entity hides in the most secret part of its being, digestion imposes itself in Bondi’s art as the paradigmatic form of all relations to the world. To be in the world means always becoming the place of a concoction, a crossbreeding of elements and objects that conspire to transform the nature of the world. Cooking is not an activity among others, but the physiology that defines the structure and life of every object and every living thing.

“When I started studying art, whether in South Africa or France, my goal was not to become an artist. In fact, I wanted to open my own gallery, which is why I started by studying art — a bit like an architect who gets familiar with materials and learns how to build a house before drawing his own plans,” says Bondi in a conversation with Line Ajan. The artist who wanted to be a gallerist has found a way to make her art a sort of cosmic gallery, in which the world itself, and its metabolism, coincides with her work. Or, to be more precise, the artist becomes a farmer who transforms works of art into greenhouses in which objects finally acquire the same status as those who cultivate them: everything lives. Each atom, regardless of the ties it has with the rest of the material, has its own life, regardless of our opinions, explains Bonde, never hiding her animist faith. Art is nothing more than realized animism, which allows the life of matter to reveal itself in all its forms.

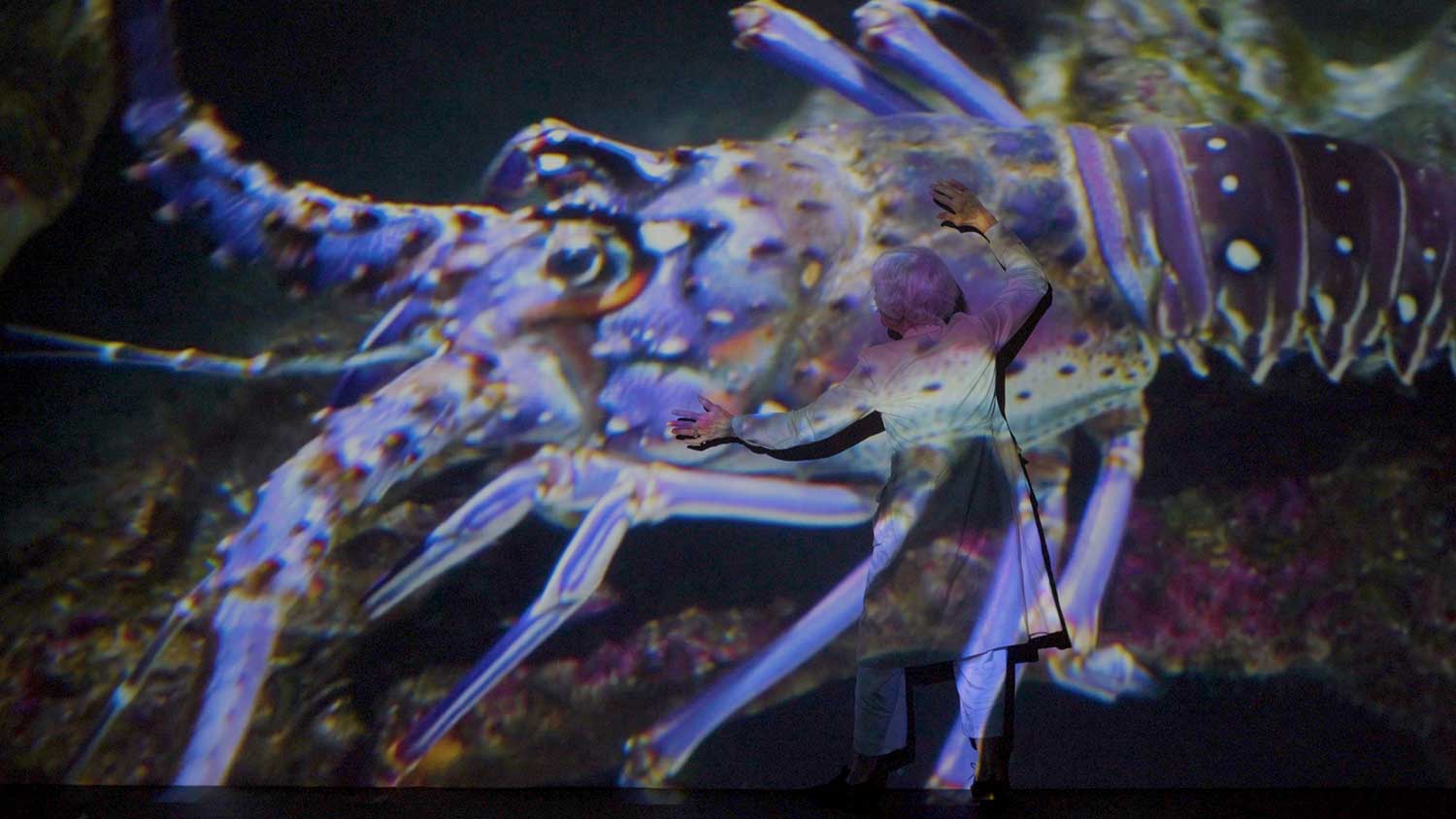

In a world where everything lives — any portion of matter, in any condition and regardless of what happens —life is no longer a succession of births and deaths, but a continuous flow of metamorphoses. In a radically animist world, nothing is born, nothing dies, but everything is transformed. Metamorphosis is everything that happens. What the artist has to do is to associate new objects to produce new life, unimaginable forms of natural history.

Thus the living objects trapped in the vitrines are not mortified like butterflies pinned to a panel, but they do not live as they would outside the vitrine either. They are stationed within an intermediary state. The matter continues to live, but according to different rules. The membrane that separates theses places from the rest of the world is also what allows them to follow another evolution, a fate other than the sea of the world that surrounds them. Each of Bondi’s installations —the vitrines and the plastic bags —thus produce a diversion of certain elements and objects from the history of the world. It is not a question of tearing them away into an acosmic and timeless solitude; on the contrary, it is about recreating a time and a space that are halfway between past and future, life and death, singularity and universality. Bondi’s vitrines can therefore be interpreted as an attempt to artificially reproduce the metamorphic space par excellence —that of the egg. Every egg is a paradoxical stage in the life span of beings —a space capable of making life exist in a state of latency that is halfway between life and death, between past and future, between individuality and its multiplication. But unlike “natural” eggs, which precede the constitution of the individual and disappear after birth, the windows of Bondi are artificial and postnatal — as if they were built by the things themselves, which in turn can never abandon them. As if they were the transcendental form, the halo of the life of things.

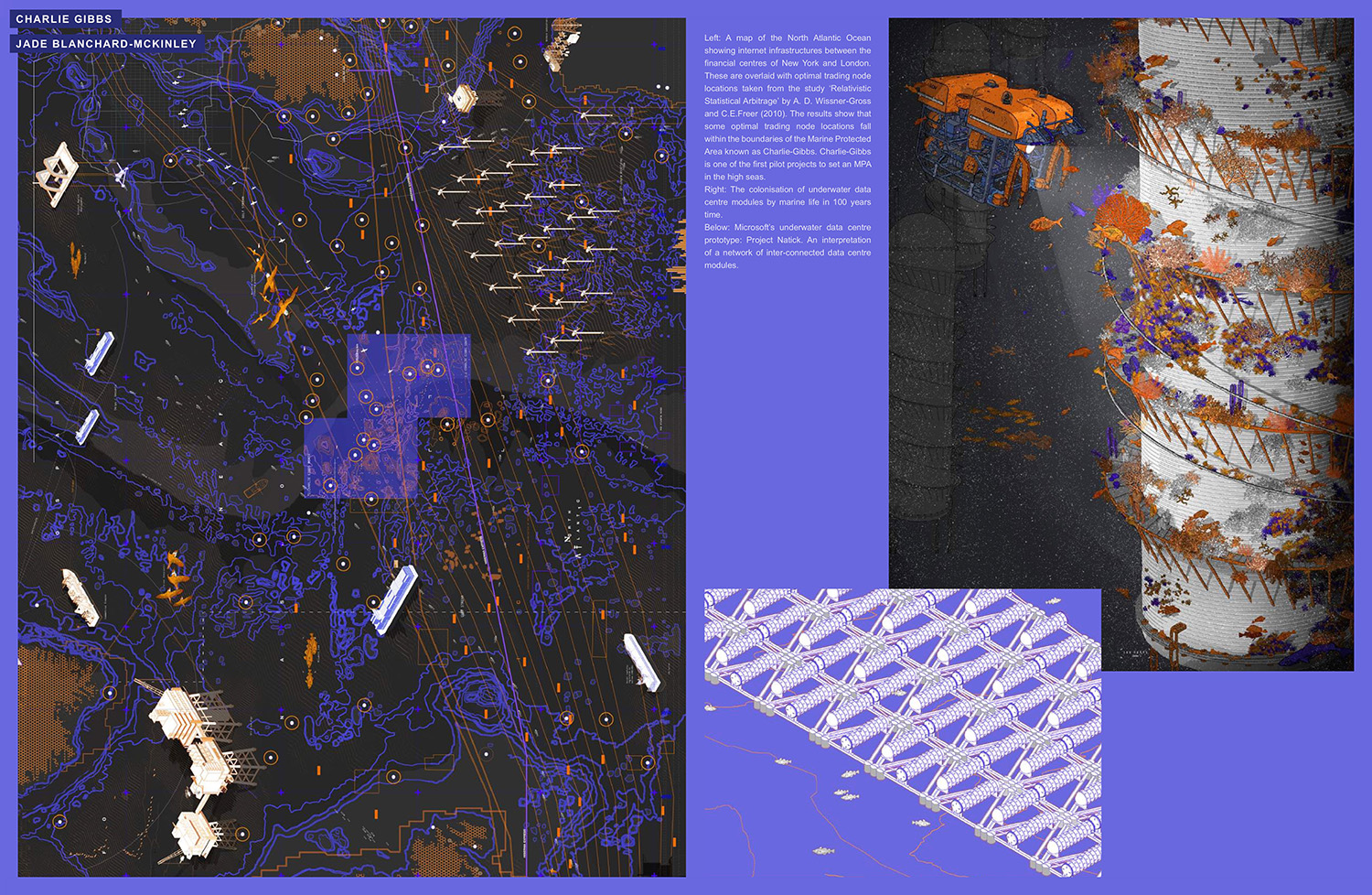

And if they are artificial and postnatal eggs, it is because they allow geographically and ontologically different objects and realities to react together, to constitute a new ecosystem. Art is a sort of curious eco-surrealism that does not limit itself to extending the limits of what we consider to be nature. The artist must now literally invent new forms of nature.

Bondi often repeats that her art is deeply linked to ecology: “Even when I don’t want it to be the leitmotif, it becomes one.” But it would be wrong to think of her art an attempt to make nature the object of artistic representation. Bondi’s is not only an expression of contemporary art; it is also an invitation to think of something as a form of contemporaneity in nature. If there is art and also contemporary art, it is only because nature has a history. And the task of art is precisely that of transforming nature into something contemporary. Her works of art are small museums of contemporary nature.

In a historical context dominated by neocolonial nostalgia for a return to premodern cultures or a civilization in which nature still exists in a purely nonhuman way,and humanity interacts with the nonhuman in direct, natural, and immediate ways, Bondi’s art seems to suggest more realistic ways to deal with the ecological crisis we are experiencing.

What we call the Anthropocene is not only the point where the whole world is anthropized and acquires a human face. It is also the point of reversal in which the human world “mineralizes” itself: culture, the human world, is no longer a sphere made and built with words, feelings, concepts. It is also and above all geology, rock, and millions of nonhuman species from which we have become inseparable. It is solely for this reason that art must be confused with a sort of natural magic.

Artists are the pioneers of a new nature and not just of a new culture. The new avant-gardes will no longer be able to worry about cultural rebirth. They must take into consideration the future of the planet — or better, the future of all matter, the life of all the atoms of the universe. But to do this it is necessary to go in the exact opposite direction from what Ruba Katrib, analyzing works by Anicka Yi, Pierre Huyghe, and Josh Kline, has called molecular sculpture. In fact, it is not a question of extending the traditional practices of sculpture by integrating new materials or new chemical dynamics. On the contrary, it is necessary to think that the life of matter is already, from time immemorial, an artistic practice. Bondi’s gesture of creating works of art that limit themselves to a closed-off portion of the world, a sort of greenhouse, is only a consequence of this awareness. The artist is a facilitator or a midwife and not a demiurge; that’s why she has to build eggs or greenhouses. The salt that Bondi so often stages —the alchemical element that has represented for centuries the power of metamorphosis of matter —is merely the allegory and the reality of the transformative force of art.