The world is drowning in data.

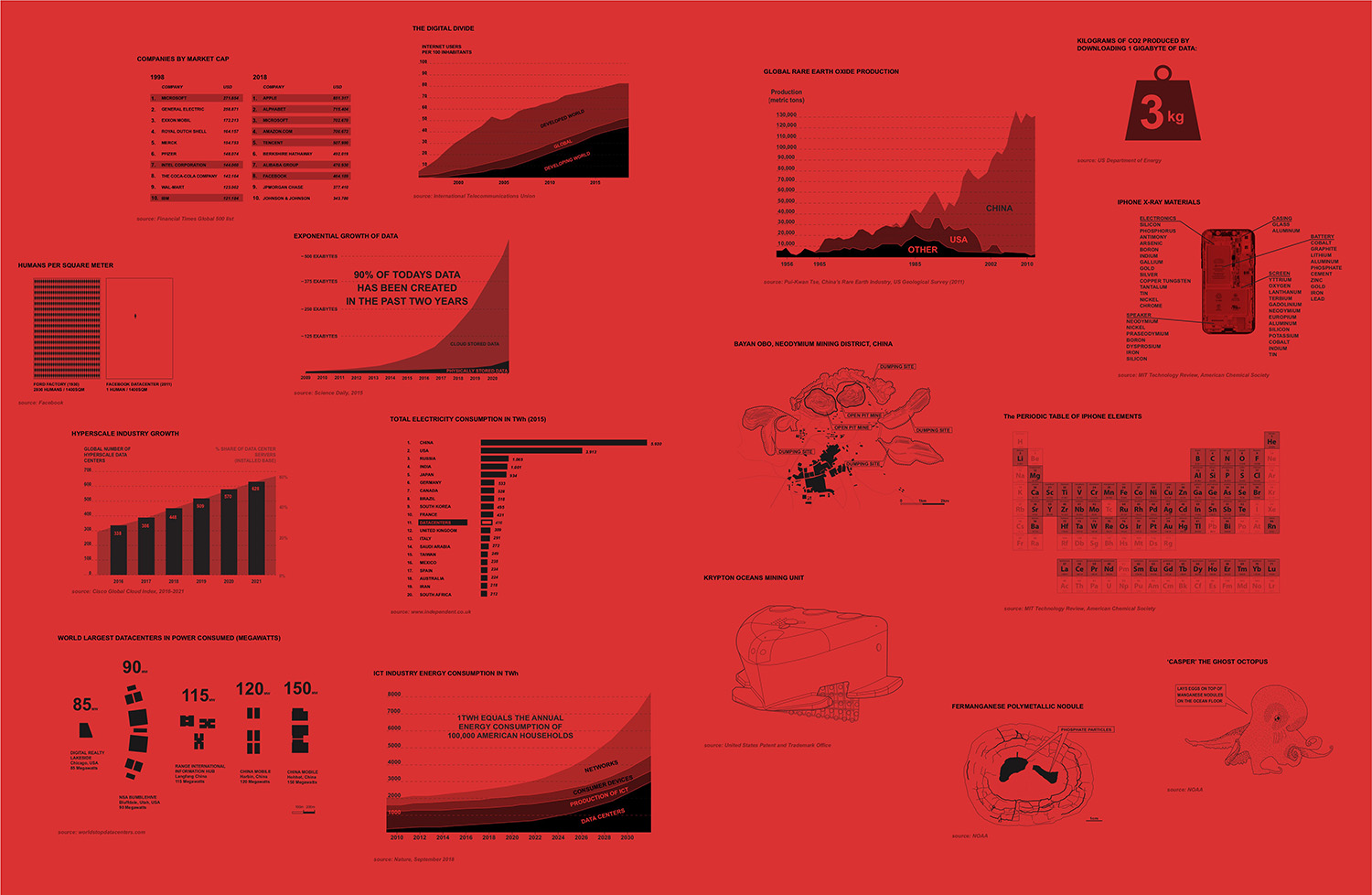

Every second, 2.8 million emails are sent, 30,000 phrases are Googled, and 600 updates are tweeted. The amount of data uploaded to the Internet in a single second is a staggering 24,000 gigabytes. Propelled by the Internet of Things, 2.5 quintillion bytes of data are created each day. This figure grows exponentially. In fact, ninety per cent of the world’s data was generated just in the last two years. While our datafied existences progressively evaporate to bytes and remote connections, the material, environmental, and spatial consequences of data production and consumption remain largely unanticipated.

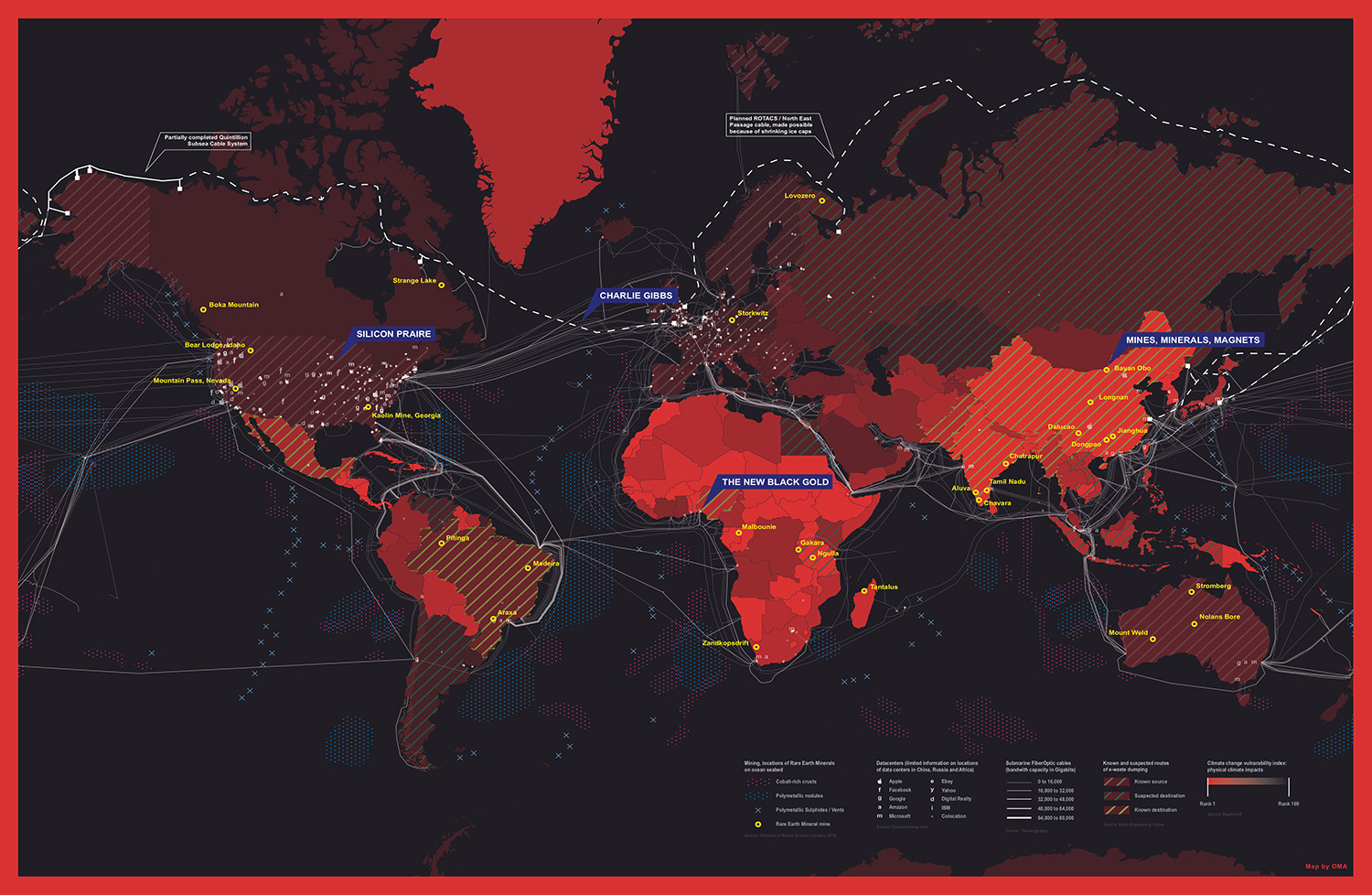

The global digital infrastructure is entangled. It coexists with and struggles against different layers of the material world: from the vast ranges of corporate and state sovereignties that regulate its operations, to the availability of energy, resources, and space.Jussi Parikka reminds us that to understand contemporary media culture we must look for those material realities that precede media themselves — Earth’s history, geological formations, minerals, and energy on which media depends. A new geography has emerged, one that knits together the infrastructure of networks, the mesh of fiber-optic cables, data centers, electromagnetic waves, and the extraction of resources. Data mining goes hand in hand with the mining of minerals to keep the system running.

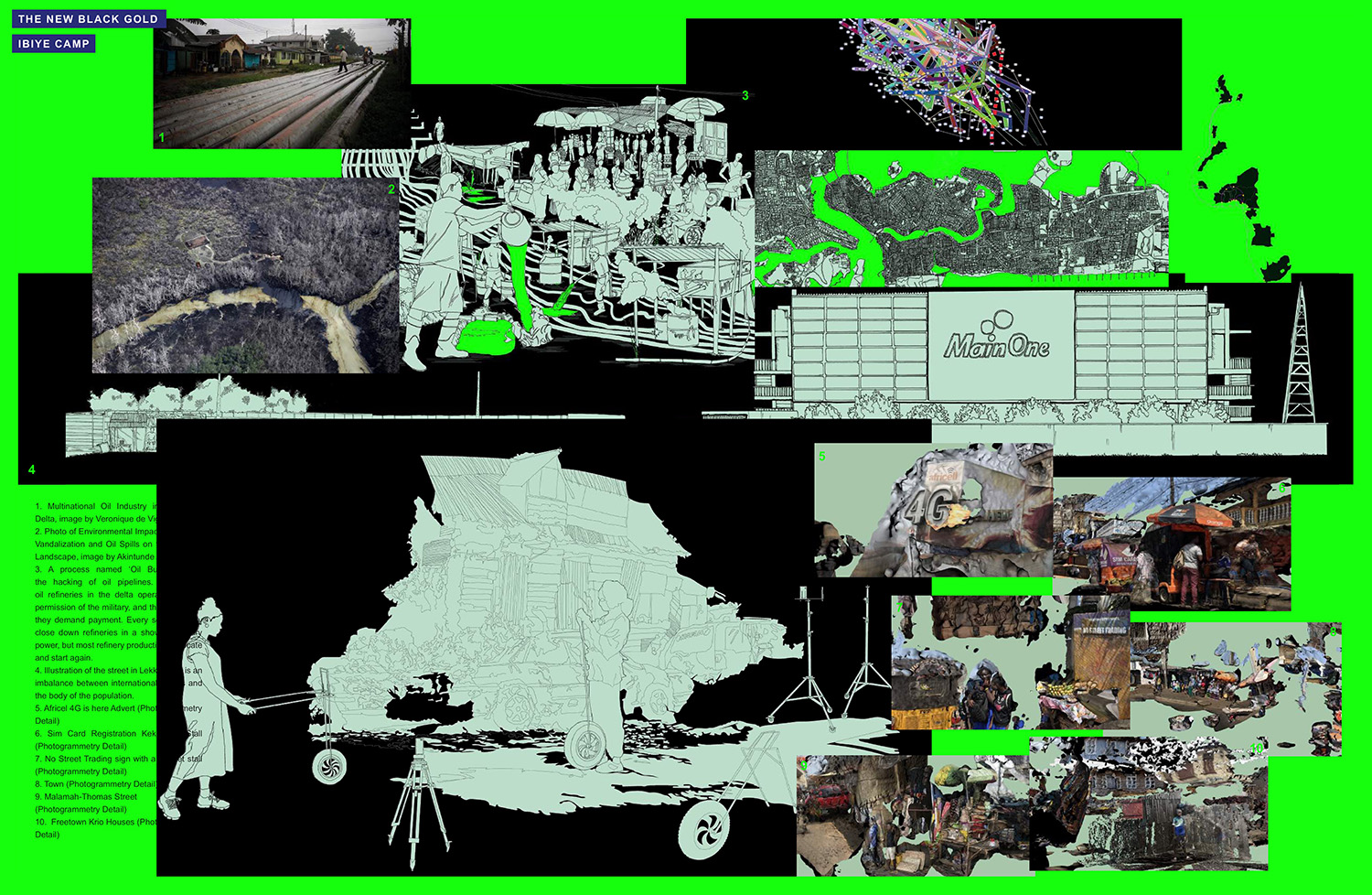

Stretching thousands of kilometers across the globe and connecting continents and users at the speed of light, a planetary mesh of fiber-optic cables is laid out offshore before penetrating inland and dictating who has access to ultrafast broadband capacity. In this way, it defines the geographies of opportunity, still largely based on old colonial ties and prewar power structures. The global digital divide reflects the persistent extractive relationship between Western countries and the rest of the world, where some critical areas take the environmental, social, and political burden of mineral extraction and toxic waste dumping needed to support our contemporary lives.

As data production, consumption, and aggregation grows exponentially, so does the massive planetary system of digital infrastructure. This convoluted large-scale operation and its associated geopolitical ramifications demand the existence of data distribution nodes. Everything that happens online depends on the seemingly unassuming industrial architecture of the data centers — facilities housing the computer systems that store, control, and use data communications and connections, and in which human presence is increasingly incidental. Data centers are a fast-growing typology, largely responsible for the massive ICT industry global energy consumption. In fact, if data centers were a country, they would be the eleventh most energy consuming nation in the world, a ranking doomed to escalate at a frightening pace.

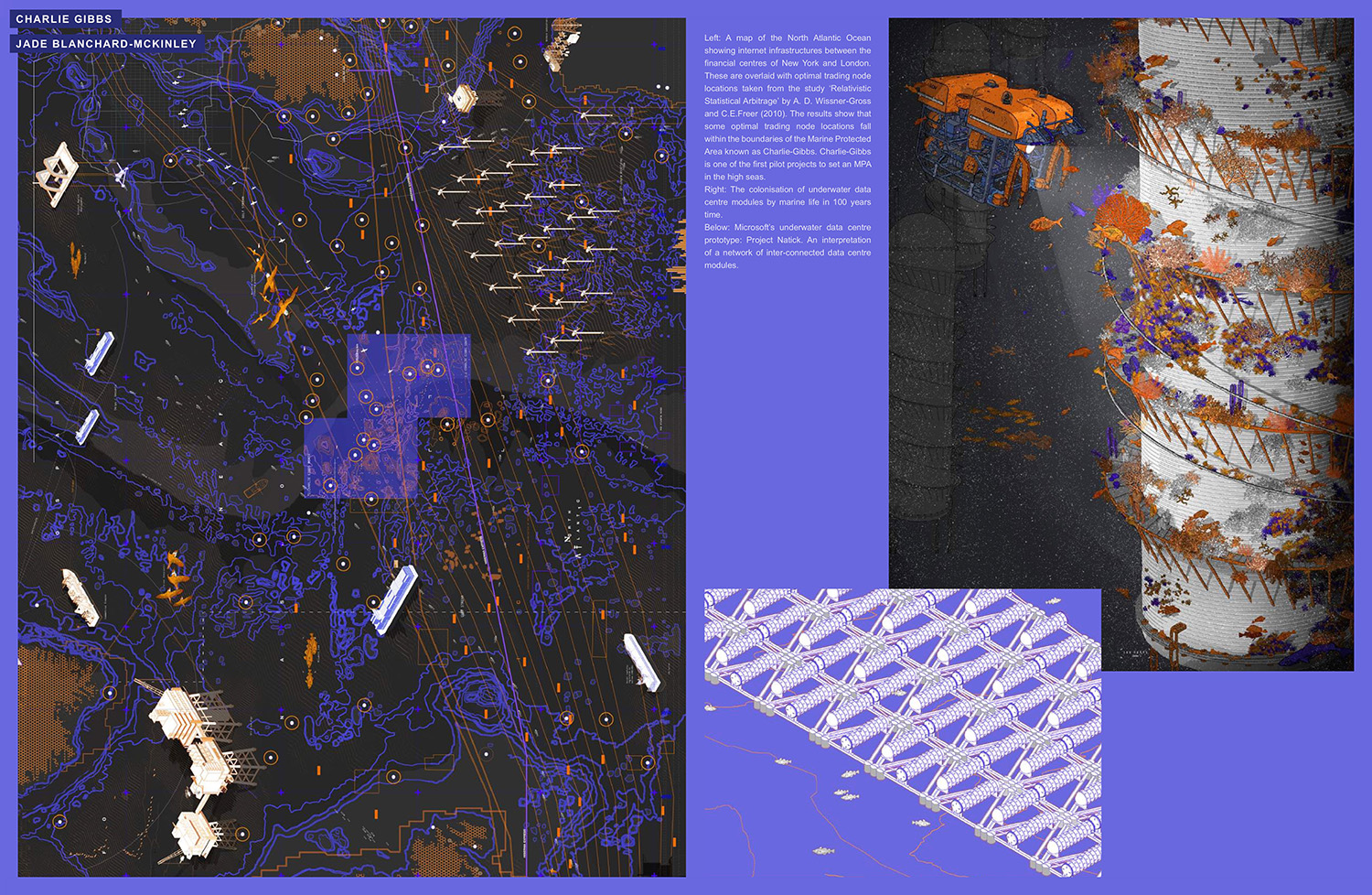

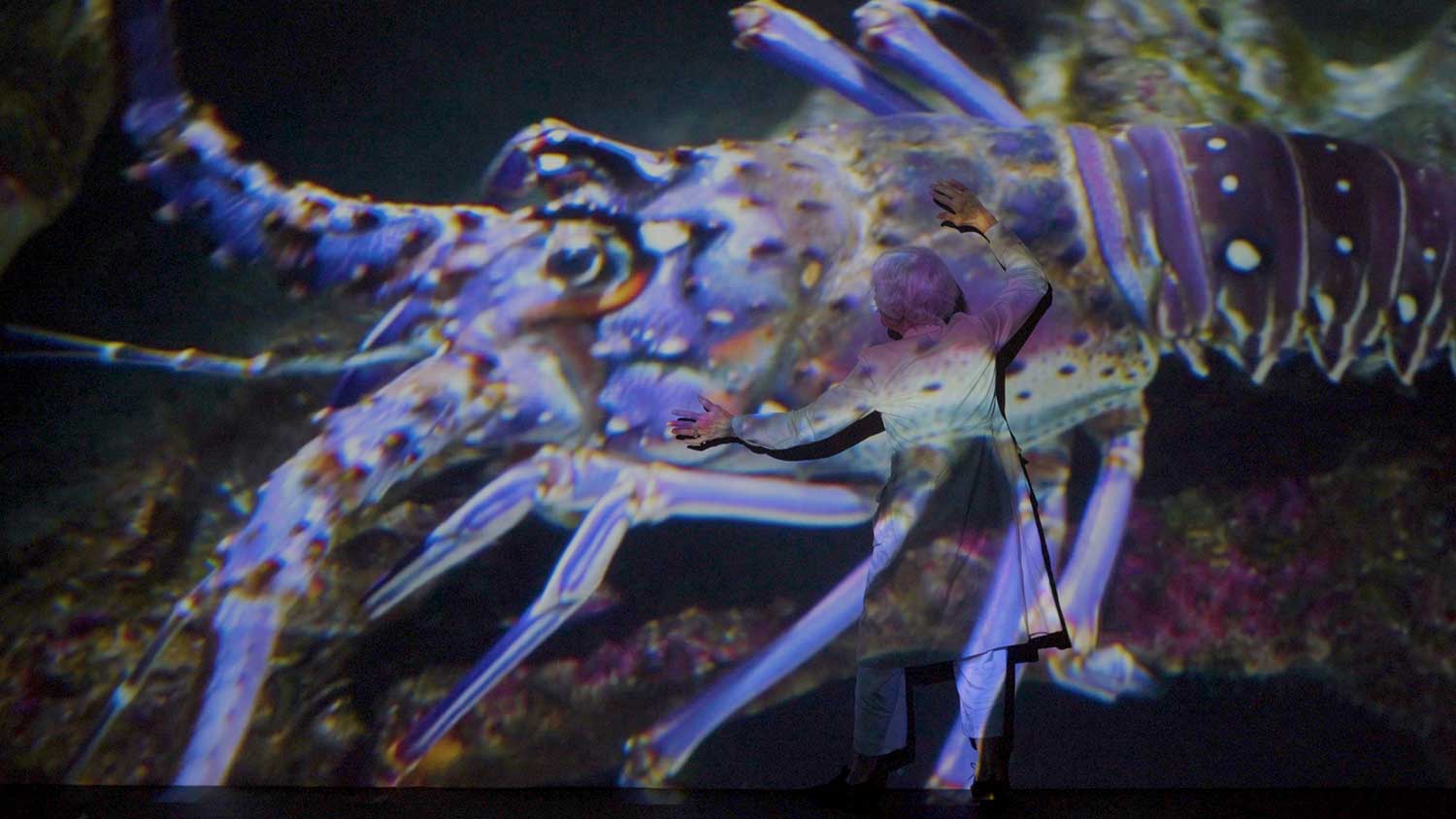

In this context, climate change paradoxically becomes an asset: the accelerating loss of artic sea ice has opened the possibility of new Northern Sea fiber-optic cable routes, connecting Europe to Japan and beyond at the speed of light. The seas are increasingly becoming contested datascapes, as the race for mineral resources moves dangerously to the bottom of the oceans, while plans for new submarine data centers are launched to take advantage of low undersea temperatures to cool servers and save energy.

This is an overwhelming scenario, one that prompts an urgent redefinition of architectural practice, based on a shared system of values and on new forms of cooperation and care between humans, machines, and other organisms. Often the discussion around the architecture of data has been confined to issues of aesthetics or mechanics: representation and accessibility, efficiency and heat exchange, the politics of the envelope, the rise of fully automated environments and the fetish of nonhuman space, etc. The real question though lies elsewhere and concerns the design of a new system of relationships: What would be a twenty-first-century institution of human and nonhuman agents and what would be its “architecture”?

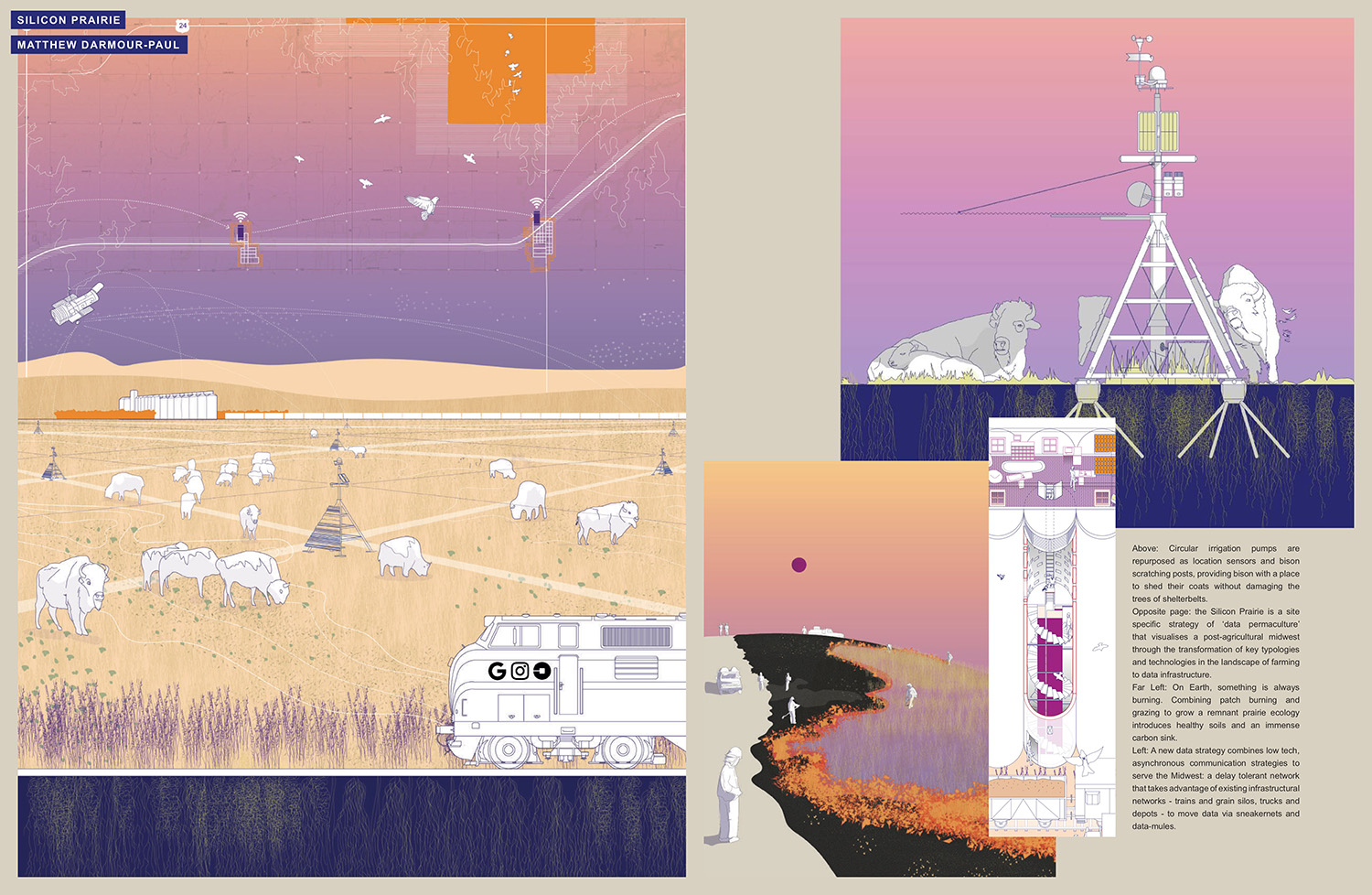

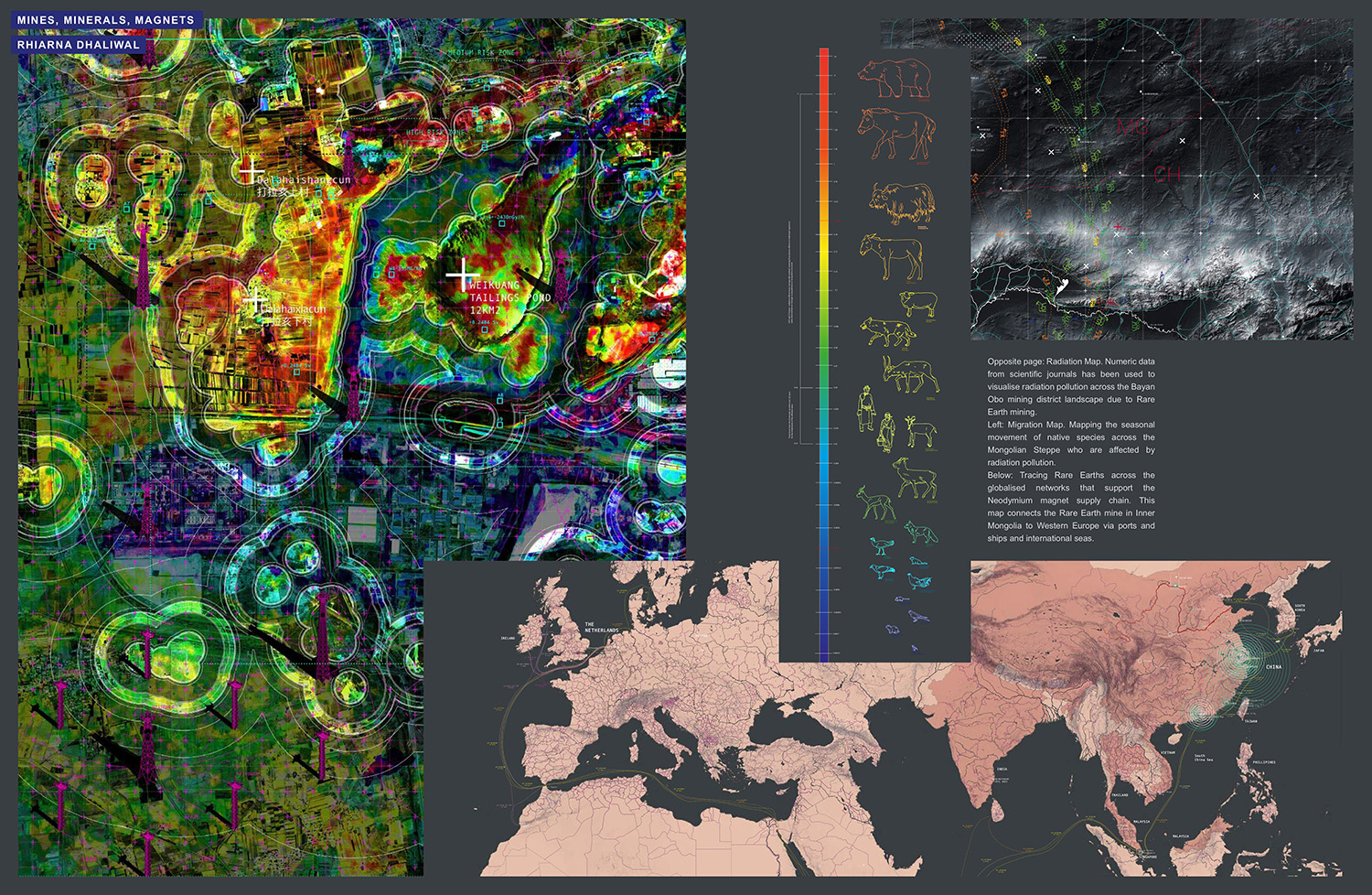

The following pages are a glimpse into an ongoing collaboration between OMA, Het Nieuwe Instituut, and a studio unit of the school of architecture of the Royal College of Arts in London. On one hand they aggregate data that cast light on the environmental impact of one of the most disruptive industries on the planet; on the other — through case studies of four students — they show possible scenarios of cohabitation between humans and nonhuman agents in four parts of the world, differently affected by the industry of data: (1) Charlie-Gibbs, a marine conservation area and a potential location for oceanic trading nodes in the middle of the Atlantic becomes a testing ground for the re-colonization of marine species; (2) strategies of “data-permaculture” envision a post-agricultural American Midwest, by repurposing farming typologies and technologies into data infrastructure; (3) the entangled relationship between oil and data in Western Africa prompts alternative ways to gather and leak data through the informal streets of Lagos and Freetown; (4)the radioactive territory around the rare minerals extraction facilities of Bayan Obo in China is re-traced with light interventions serving as a life support system to local species.