Andrea Bellini: Let’s start with trash, which is very often synonymous with history. Following the assault by Donald Trump supporters on the US Congress, the photo of a certain Jake Angeli was published on the front page of newspapers across the world. A photogenic guy, Angeli is now infamous as the horned, self-styled Q-Anon Shaman, pictured rampaging inside this “sacred building” of American democracy with a manic grin. Someone has superimposed the Gucci logo on this photo, as if to say that the look of this ultra-right-wing “patriot” closely resembles that of Alessandro Michele, one of the coolest fashion designers in the world. This association is pretty funny, but it is also thought-provoking. What does it make you think?

Babak Radboy: Well, Gucci and Alessandro are like the Bacchanalia and Bacchus — and here you have a shirtless man with horns, storming the Capitol. You have this vision of excess, carnival, an unleashed libido that is supposed to be “liberal” — activated on a historic scale by the Far Right. And then you have “progressive” people finding these strange words coming out of their mouths like “treason” and “sacred building” — and demanding more censorship, surveillance, and security. That’s a double bind, and what we want is disentanglement. So I would start by stating that anything which is deemed beneath discourse is kept there by the police.

So ask yourself:

A: What aspects of my ensemble require policing?

B: What changes could be made to bring this requirement to an end?

AB: Don’t you have any easier questions for me? Just kidding, ambitious questions are really my thing. Well, I think this idea of “no policing” unfortunately makes sense only in Dante’s Paradise, at least for the moment and for a while.

You know, I was thinking that nowadays art magazines — such as this one, among other major players — are full of talk about changing the world.

Don’t get me wrong, I find this very good. Indeed, it’s better than reading someone who still writes seriously about biennials, art fairs, or abstract paintings. But let’s get back to something more practical for the moment; let’s talk about the brand and how it’s organized. It seems clear to me that you have a very efficient division of labor (as it should be): there are those who design, those who sell, those who speak. How did Babak and Telfar meet and where? On what is this very special energy that binds you based?

BR: I find it hard not to reply to your aside about police and paradise. This is not an abstraction. You are saying that you require Black people to be policed. You are saying it on behalf of a “common sense” — which of course means white people — and you are doing it in a very lighthearted manner. So what else? You are also talking about what you imagine are our divisions of labor. Well, it’s not so clearly divided — and the things you don’t know, hear, or see play the most “practical” part in our operation. We pray it stays that way.

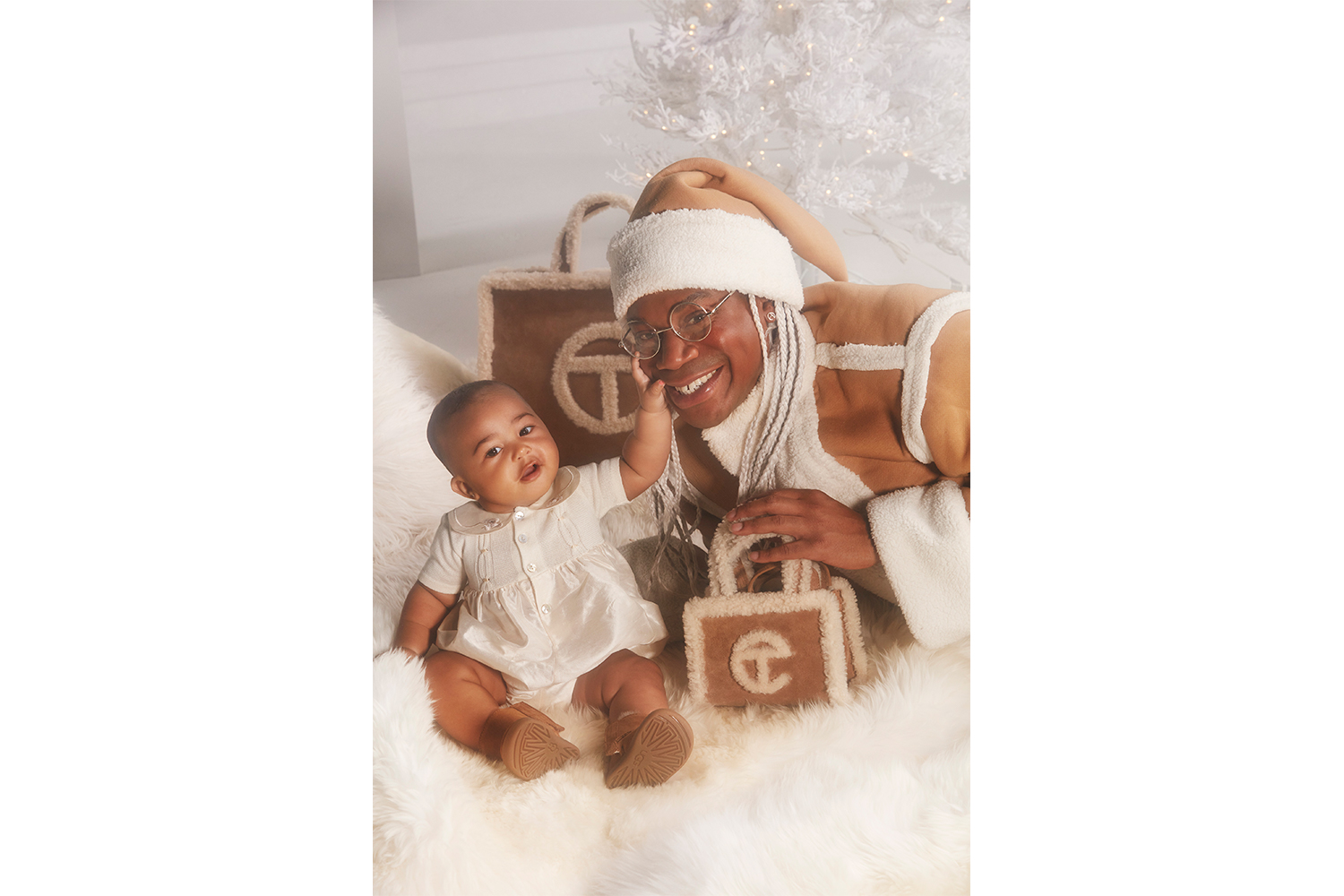

AB: In stating that no police is only imaginable in Dante’s Paradise, I was thinking of a pervasive, global form of control of which people are not necessarily aware. What I meant was that artificial intelligence and new algorithms (such as those dedicated to text generation programs) are gradually taking control of our behavior, not only in the economic sphere but especially in the political one. This form of capillary and global control, is as odious and dangerous as the ignoble form of police control in the street. Unfortunately, both are a sad reality. But let’s continue the interview talking about Telfar. As an Italian I really have a passion for your motto: “Telfar: not for you, for everyone.” This is actually the same philosophy with which FIAT, the Italian car manufacturer, sold its 500 model after World War Two. A car for everybody! I don’t know how much FIAT cared about the happiness of the finally motorized proletariat, and this doesn’t really matter; in the end, FIAT’s goal was to sell a lot of cars. What’s your goal?

BR: Yes, but our motto is specifically not “it’s for everyone” — our motto is “not for you, for everyone.” That is not a validation of “you” or “everyone.” That’s a message that questions the grounds of address. And it’s a questioning that is meant to remain a questioning. So when you ask me what our “goal” is, it presupposes a separation that originates in finance before making its way to Western philosophy.

What we want to do is to erase the separation between what we want and what we do. If we could empty the word of every other meaning, you could call that freedom.

AB: Freedom, of course, it’s another good thing. But when we talk about freedom we always run the risk of falling prey to abstraction, which makes the exercise of freedom, especially moral freedom, a moralistic myth. Could we say for example that Telfar’s freedom is one from luxury? Is this freedom something you consider transgressive?

BR: If I’m speaking about freedom I’m talking about time and space, not things. But a freedom from luxury is a way of saying a freedom from scarcity. Maybe we can’t claim to free people from scarcity — but we can sabotage the conversation. I think sometimes about how the right and the left — in wildly different ways — both consider poverty to be a crime.

I think we are in error when we imagine wealth as the solution to poverty. The two are at war. So what would it look like for poverty to win?

AB: When we met in NYC I had the feeling of facing not only you and Telfar but an expanded family: around the dinner table there was Lauren, Marco, David, and Solomon, members of DIS collective. To what extent is your family part of your creative process?

BR: We do things primarily to do them; primarily to create the space and time in which they are done; sharing that time and space with the people we do them with; and extending that to a wider group of people who we don’t predetermine as an “audience” or “viewer” or a “customer,” etc. It’s not wrong to call that “community” or “family,” but it puts the emphasis in the wrong place and makes it all kind of quaint. I prefer the word “conspiracy.”

AB: You are right, the term “conspiracy” certainly seems more contemporary. In a certain sense, “conspiracy” and “family” are almost synonymous, not only in the US and not only today. Emperor Constantine the Great, the one who legalized Christianity in the Roman Empire, had both his son and his wife executed. Maybe he converted to Christianity before he died to save his soul. Who knows? So tell me about your conspiracy with contemporary art.

BR: The literal Latin translation of conspiracy is to breathe together. I don’t think we conspire with contemporary art. That thing, “contemporary + art,” is a claim about time and a claim about humanity. Specifically a claim of victory — over time and humanity. This is a historical victory with actual wars and actual subjugations — but at the same time a claim to victory over history itself.

To be infinitely contemporary is to say your civilization will never end — which is to say our subjugation will never end. We would love as many people as possible to turn the corner on this nonsense.

AB: I understand what you mean, although we could still see art as a claim on language. The concept of time, humanity, or civilization, are cultural categories, so they change, sometimes very fast. Only the violence of capital seems impermeable to any change. And the world of so-called culture, aside from expressing some vague sense of guilt, which is very strong in the art world, can’t do too much to eliminate this violence. Do you think that you can do something about it?

BR: I’m not operating on that model. Capital is not something preying on civilization — civilization is preying on life. There is no “violence of capital” — capital is the way in which we administer violence.

To be quite frank — as a European you are heir to a totalized knowledge system which has tried to disentangle itself from violence via the concept of capitalism as an exteriority to civilization. Just as the mass material project of slavery is disentangled from the intellectual project of the enlightenment, which was its prize. From where I stand they are the same project.

There is no struggle between knowledge and violence. Knowledge itself is the problem — not in content, but in it’s form: as a ledger and store, in its ability to mediate and discipline struggle on the level of language.

In its impoverishment of the imaginable. So if you are asking me seriously if I can do something about it — I can only do so in imagining my freedom as a kind of catastrophe for you.

AB: The project you are working on, which will be part of the next Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement (November 2021), is your most ambitious project to date: it’s a streaming series rather than a traditional ready-to-wear line, something in between music, film, and designed objects. Can you tell me a little bit more about the project? Who is working with you and what do you want to achieve with it?

BR: We would like to avoid that description if possible! There is an extraordinary period of time represented in what we will finally include in the Biennale. In that time we have structurally transformed our own “place in the world” and are continuing to try to dismantle, disentangle, and divest. This has and is happening in the form of a social practice, an ante-politics, a counter-knowledge — and we yearn for something closer to a non-knowledge. Not knowing is an ideal approach.

AB: Yes, not knowing can be an ideal approach, but it can also be just another good slogan. I think we are all very curious to see what you’ll be able to put together this year. It’s already been ten years since you presented a collection at MoMA PS1 in 2010. Would you still describe your practice as a “design philosophy of simplexity”? A sort of platform where you “explore the fashion system’s dichotomic understanding of a brand being either simple (i.e. commercial) or complex (i.e. avant avant-garde),” as once I read in DIS Magazine?

BR: We prefer not to say.