When one endeavors to write about the painting currently being produced in a given country, it is very easy to fall prey to the idea of providing elaborate, all-encompassing theories. However, if experience teaches us anything it is that the closer one looks, the greater differences become, and providing an overview of the work produced by artists tied together merely by milieu, medium and time period, proves to be if not impossible, in the very least problematic, and at its worst a facile fictional exercise. One should also not forget to ask oneself whether the idea of nationality is at all relevant to current artistic practices — whether there is such a thing as a “national temperament” in art. That, however, is an entirely different discussion. One could perhaps search for possible unifying ingredients permeating the work produced in the allotted geographical region, or, to use an entirely discredited and possibly irrelevant word, the “spirit” present in the works produced. As impressionistic as this may seem, it appears to be the only safe option when attempting such a discussion. One should also be conscious that these unifying ingredients will be seen reflected in the production of other loci, and in its turn will reflect the production of diverse regions, thus limiting the relevance of such a nation-based discussion.

To discuss the breadth of contemporary Brazilian painting is beyond the scope of this text. However, it is fruitful, I believe, to contribute some annotations on possible ideas based on the formal and technical explorations of image construction found in the work of four artists born in Brazil at roughly the same time and active here since the beginning of the ’80s: Leda Catunda, Daniel Senise, Rodrigo Andrade and Beatriz Milhazes. What seems to bind this remarkably heterogeneous group is the fact that they are not painters who are artists, but rather artists who make use of the medium of painting, with very little or no regard to the technical qualities or traditions inherent to the application of paint to canvas. To debate the painterly qualities, or finish, of the works produced by them would be beside the point, for they make use of a traditional medium in order to compose and recompose images largely based on collage techniques, evoking traditions and debates that originally reached Brazil—and all of what was once known as the “New World”— by means of reproductions and not entirely reliable interlocutors. One could describe their binding quality as that of being the copy of the copy of the copy of the copy, and thus, not at all a copy, but a reinterpretation. This imitative quality has always been present in the work produced in Brazil. The whole of the culture produced here was, for a long time, nothing other than a transplantation of European culture, influenced obviously by its interaction with other cultural modes. It remained, however, thoroughly entrenched in its historical European substructure. It is only recently that this imitative quality has been used to its own advantage as a determinant factor of artistic production. I do not lay claim to any originality in the points here made. They have been expounded upon by a number of art historians, critics and curators in the recent past when dealing with contemporary Brazilian painting, and they seem to form the structural basis upon which any discussion of that theme is currently based.

Going back to the point regarding the lack of painterly virtuosity in the work of these artists, one could debate whether the work produced by two of the above-mentioned artists, Leda Catunda and Daniel Senise, could be classified as paintings at all. Leda Catunda’s pieces make use of paint, brush and canvas, the traditional technical triumvirate of painting, but also of synthetics, towels, blankets, pillows and all manner of textiles. This queer use of materials produces monstrous womb-like objects, upholstered canvases, paintings-cum-sculptures. These are referred to by the artist as a kind of “maternal painting” due to their not only warm and comforting materiality, but also because of their intensely menacing qualities. They are hugely ironic, not to say cynical, in their use of imagery and references, evoking at times a softened take on Concrete and Neo-Concrete works dating back to the ’50s and ’60s. They are, despite their frolicsome nature, deeply entrenched in painterly problems and discussions, as is made clear by Catunda’s many watercolors, most of which are divested of the monstrous, nana-like quality of her larger-scale works. In this quality they differ remarkably from Daniel Senise’s expansive, all-encompassing canvas-collages, which seem to exist outside of the space delimitated by their physical borders. These could be referred to, in very colorful terms, as vast, infinitely germinating metaphysical structures. His work has moved away from images and figures utilized in the ’90s and early 2000s to depict what can be perceived as empty spaces, structures of buildings or shelve-like structures constantly rearranged, broken down, subsequently restructured and occasionally disturbed by nebulous shapes positioned upon them. The works are constructed as collages from cut-up bits of previously stained, brownish canvas, at times recalling the ocher marks of the Shroud of Turin (it is worth remembering that his work has always made use of Renaissance art-historical references). The organic state of the marks from which the paintings are constructed becomes ever more disturbing when contrasted with the Borgesian walls, shelves and interiors emptied of living human presences produced by the artist. This play of presence versus non-presence, and reverence for and the ensuing breaking down of tradition, allied to the rather disturbing aspect of the difficulty of classifying his production — we should remember that form and content can never be truly separated when dealing with art — make for very uncomfortable, in the best possible sense of the word, viewing.

Moving onwards to the more classifiable painters here discussed we come to Rodrigo Andrade, an artist who deals with the essential building blocks of painting. His paintings contain the basic elements of the craft, namely color and form. Atop white canvases he places beefy slabs of oil paint in varying shapes and colors: squares, circles, rectangles and triangles of pink, yellow, orange, blue, etc. The oil paint is applied with molds in very thick layers impeding them from drying entirely, the oil thus retaining its material vitality. Despite their obvious simplicity, his paintings work with the notion of building up surfaces and the qualities inherent to such an action. The tension created with the placing of shapes, as well as colors, in opposition to one another make for intensely vital surfaces, essentially collages of shapes made out of paint, and referencing the same Concrete and Neo-Concrete movement cited by Catunda in her works. Andrade has recently moved towards the building up of figurative images, as one could see during the 29th Bienal de São Paulo, where he presented a number of large-scale paintings depicting urban nocturnal scenes. He still utilizes the same pasty, chunky application of paint, dealing more with the physical qualities of wet, oily paint and its subsequent metamorphosis into dry matter than image-making per se. What will happen presently remains to be seen.

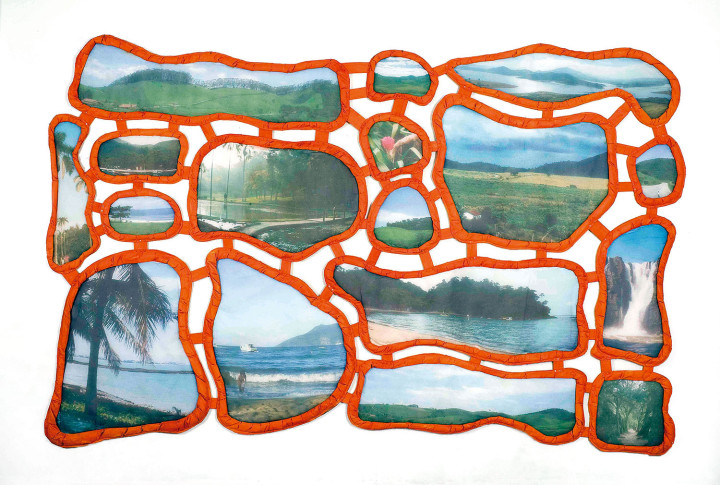

Beatriz Milhazes is undoubtedly one of Brazil’s best-known artists due to the high prices fetched by her paintings. Invariably dubbed “seductive” and dealt with according to a simplified understanding of what “Brazilian” means — Gisele Bündchen, football, carnival, bossa nova, baroque volutes, Rio de Janeiro, etc. — her work has suffered a great deal critically due to its obvious visual lushness. However, it is apparent that her work functions within a much deeper intellectual plane. In her colorful and playful paintings one can observe the juxtaposition of diverse elements and art-historical references ranging from Vasarely to Titian. Her method of painting is essentially a development of collage techniques. Ordering different transfers of layered paint from plastic sheets onto canvas, she composes what is in essence a collage produced with paint. Looking closely one will find the same recurring shapes and motifs, giving strength to the idea that she could potentially create countless rearrangements without ever repeating herself, something akin to the infinite construction possibilities offered by the Lego brick. This slow and remarkably meticulous process makes any spur-of-the-moment decision virtually impossible, demanding a good deal of patience and planning on the part of the artist. This, in effect, reduces spontaneity and deepens the idea of her work functioning more as an intellectual project rather than a sensuous daydreaming reverie of tropical flowers and curves.

These short annotations seem to point to the fact that the strength of the painting currently being produced in Brazil lies precisely in its acknowledgement of its historically marginal status, and in its use of this status as a starting point. By taking tradition in its received format and turning it upside down by use of strategies foreign to it, and disregarding the technical aspects inherent to this same tradition, these artists have arrived at painterly solutions that are illuminating in their refraction of the outside world.