In these ominous images we see the dark vision of humanity that has characterized Wattuya’s work for much of his life. A uniformed firing squad — a faceless unit of automaton-like executioners — aims at a red-hooded captive kneeling in a corner. Islamic State fighters in black garb brandish rifles, bayonets, and pistols, in a gesture of defiance. A pristine row of M16 automatic assault rifles used by the Thai Army is on display.

Thai artist Tawan Wattuya’s latest painting exhibition, titled “A Multitude of Possibilities,” at Hatch Art Project gallery expresses disdain for Thailand’s power-hungry military government and the periodic use of violence by the Thai Army against civilians.

Memories of traumatic historical events, such as the 2006 coup d’état and the Thai Army’s deadly response to the Red Shirt demonstrations in Bangkok in 2010 and 2011, find embodied expression in Wattuya’s paintings. The artist recalls the use of highly trained military snipers to shoot unarmed demonstrators with live rounds, and the indiscriminate discharge of military weapons, including M16s and other automatic weapons, directly into dense crowds.

As much as Wattuya tries to forget, the need to remember remains understandably urgent. The continuous interrogation of the past in light of present-day concerns remains a profound moral issue for the artist. “Thailand has too many soldiers; they are not used to fight the enemy, but its own people,” says Wattuya. “Why have we become so dark and cold, so murderous and cruel?”

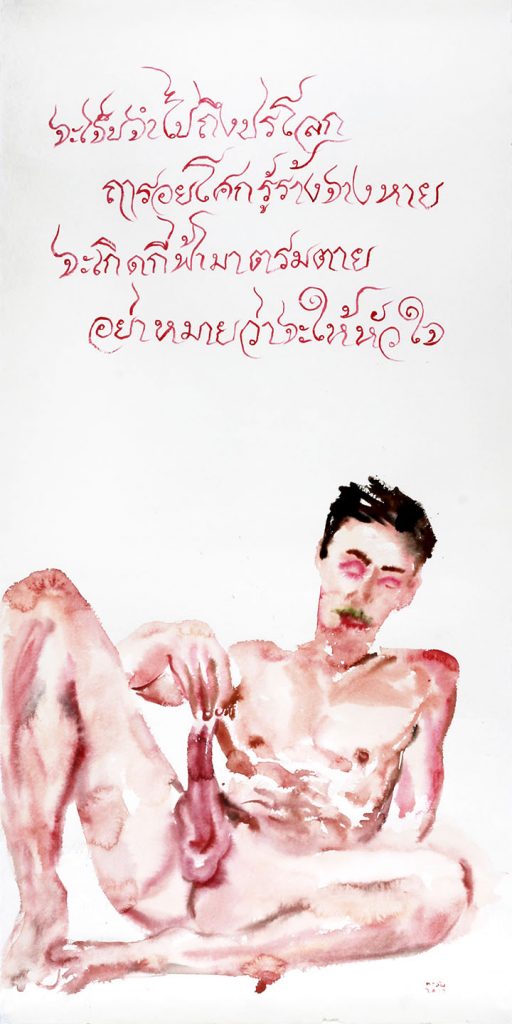

Taking center stage in the gallery is a series of overtly pornographic watercolors. All three works depict the parted thighs of a naked man and two naked women, inviting the audience to view their genitalia. There is little ambiguity here; this is the erotic orifice, surrounded by blurred pubic hair. Variously titled Sinuous(2019), Painful(2019), and I Love You(2019), Wattuya’s paintings feature poems and quotes from Thailand’s best-known royal poet, Sunthorn Phu (1786–1855). Two of the three poems suggest that it’s best not to trust humans because they are so terrible to each other; the third speaks of pain. By making the figures in his paintings the object of a voyeuristic gaze, Wattuya challenges viewers regarding how a society can recover from the devastation of its past. Can viewers look beyond the superficiality of civilized society to discover who they really are? Is it possible to understand the pain, loneliness, and anxiety of others?

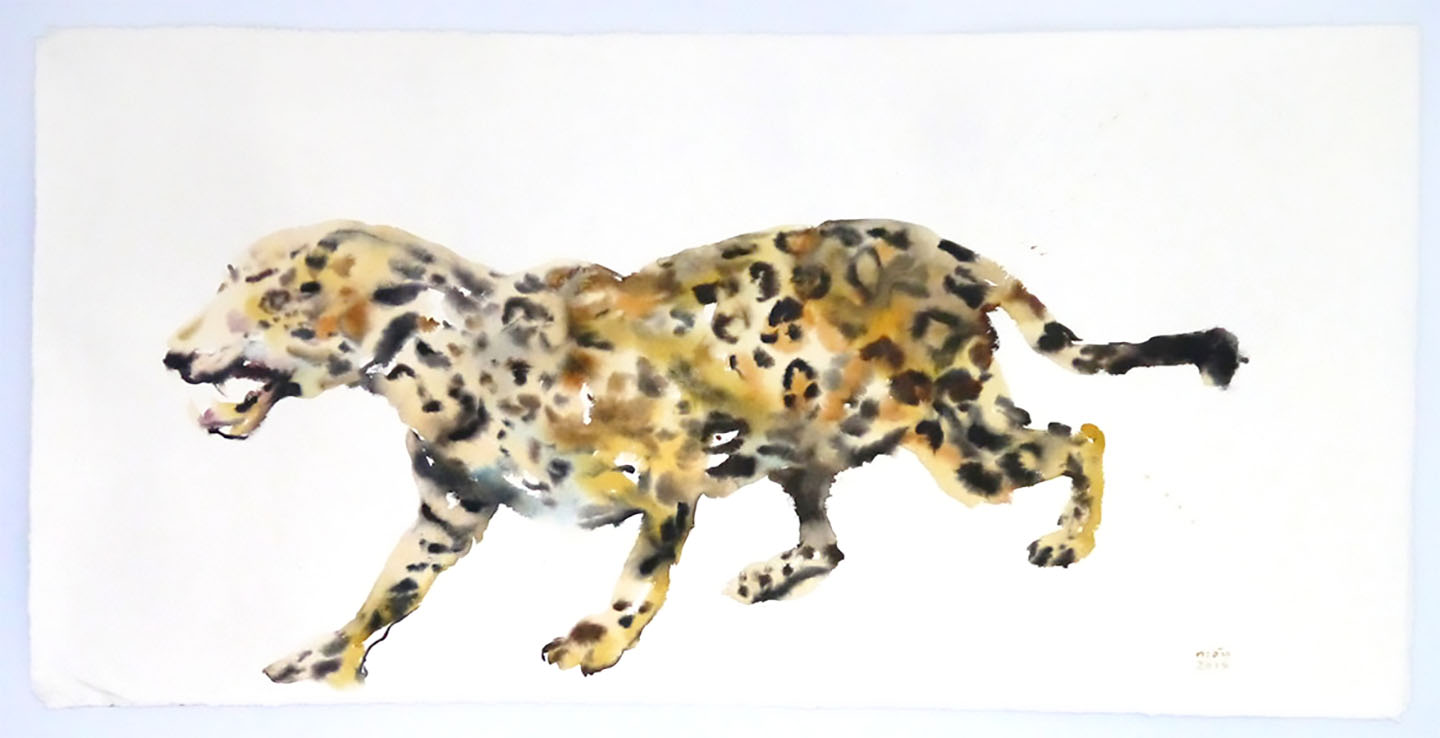

In his watercolors, Wattuya often chooses subjects that mock the many follies of civil society — in particular, contemporary Thai society. Elsewhere, a cheetah approaches in a threatening manner, then a lion, and finally a Brahman cow. “Every creature I paint has both human and animal attributes, which clearly symbolize the state of those human beings who have acted bestially,” says Wattuya. One imagines the noise of hunting in the gallery, the Brahman cows running through the forest, chased by cheetahs and lions that catch and rend them. In another work, Cabinet(2016), he paints homeless street dogs in Bangkok, in a cleverly profane approach to questioning dominant constructions of Thai power and authority. Whether we label Wattuya a watercolorist or activist is not the key issue. The real question is whether Wattuya’s antiestablishment spirit will continue to rebuke falsehood and speak out for truth and justice. Hopefully, he will continue hammering away.