A hole in the wall greets visitors to “Energies,” an international group exhibition at the Swiss Institute in New York. The square opening punctures a hollow wall that has been constructed by New Affiliates out of exhibition waste collected throughout the city. Suspended in the hole is a balsa wood fan by Nick Raffel, through which one can catch glimpses of other viewers as they read archival materials affixed to the wall’s backside. Aptly, the subject of this extensive research is the Eleventh Street Movement in New York’s East Village during the 1970s. A landmark wind turbine was installed on the roof of 519 E 11th Street, which generated enough electricity for its community in the midst of the 1977 blackouts. With this alternative model of regeneration, the movement disrupted the monopolized distribution and administration of power by the oil corporations that caused the outages. The makeshift wall is adorned with a giant saw on the top, overseeing the subsequent changes ignited by the radical drive of this community, whose efforts extended from their own immediate solution to having lasting effects on the future of energy production and regulation in the US.

How does this history inform our present ecological crisis? By expanding the curatorial scope of the survey to include a wide field of activities and manifestations of energy and power, viewers are made aware of how each can be contingent upon the other — and in the process reconceptualize their various misalignments.

Catastrophe fuels the corporate fire in Becky Howland’s installation Oil Tankers on Fire (1983/1996/2024). Comically rendered orange flames exude from five disks on a low shelf. This lineup of fuel containers, each labeled “SHELL,” “EXXON,” etc., foregrounds a plume of dark smoke painted on the wall, which reaches to the ceiling. In the corner, Ximena Garrido-Lecca’s two-channel video Yacimientos (2013) displays typologies of damage to the Peruvian landscape of Cerro de Pasco, caused by extensive mining enabled by US-funded infrastructure. Silence rings in the disquieting hum of the old video monitors. In a similar subtle vein, Vibeke Mascini’s work exudes a peculiar scent in its own gallery. Staged on a pallet jack, Instar (3.9 kWh) (2024) runs on drugs by deduction: the artist sources energy from confiscated cocaine, incinerated as a means of supplying power to lithium batteries that drive a nebulizer that in turn emits a slightly intoxicating scent. Thus Instar sits at the intersection of two axes of power, political and natural.

Several of the works on display identify shifting sources and distributions of power. The “Afrolampe” drawings series (2021–23) by Jean Katambayi Mukendi traces the paradox of copper, whereby excessive mining and export of the metal supports green energy in the Global North while leading to constant outages in the artist’s native Lubumbashi (DRC). In a formal play of positive and negative, these emblems of electricity illuminate imbalance: the ballpoint ink bleeds, outflows, and stops short, leaving the designs half empty. In Skievvar #2 (2024), Joar Nango reinvents his indigenous Sámi tradition of window-making in northern Norway by erecting an elongated wooden frame stretched with dried halibut stomachs — turning an interface into a case of monumental architecture.

In the basement, struggles around energy take on more covert and contextualized forms. Liu Chuang’s Untitled (The Festival) (2011) sees the artist lighting an anonymous fire and sustaining the ignited baton with wastepaper from the bleak streets of Dongguan China. Blinding light is emitted from Saba Khan’s Indus Water Machine (number 3) (2020). At the center of this retro-futuristic work are the geopolitical legacies of the Indus Waters Treaty of 1960, which divided eastern and western rivers between Pakistan and India.

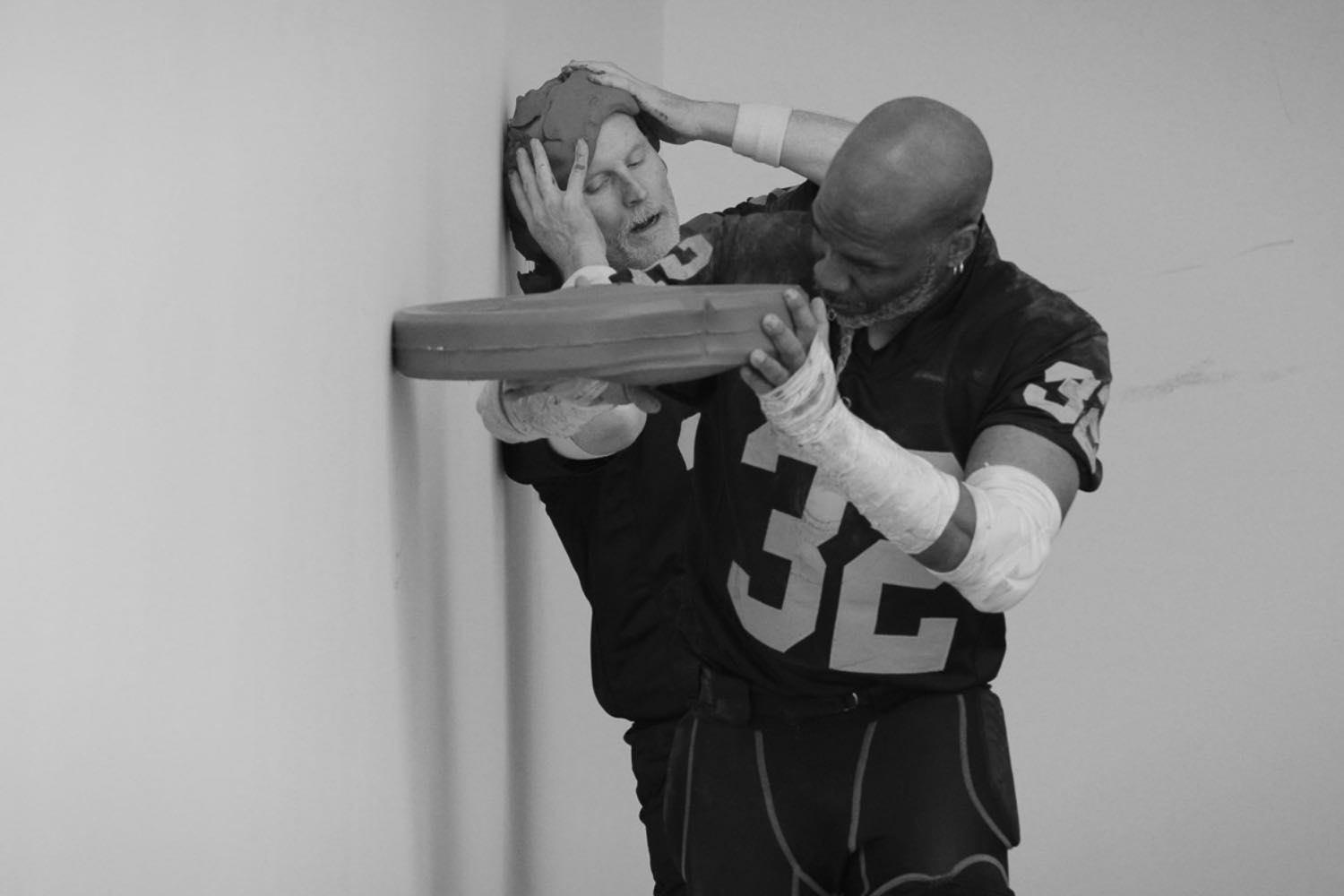

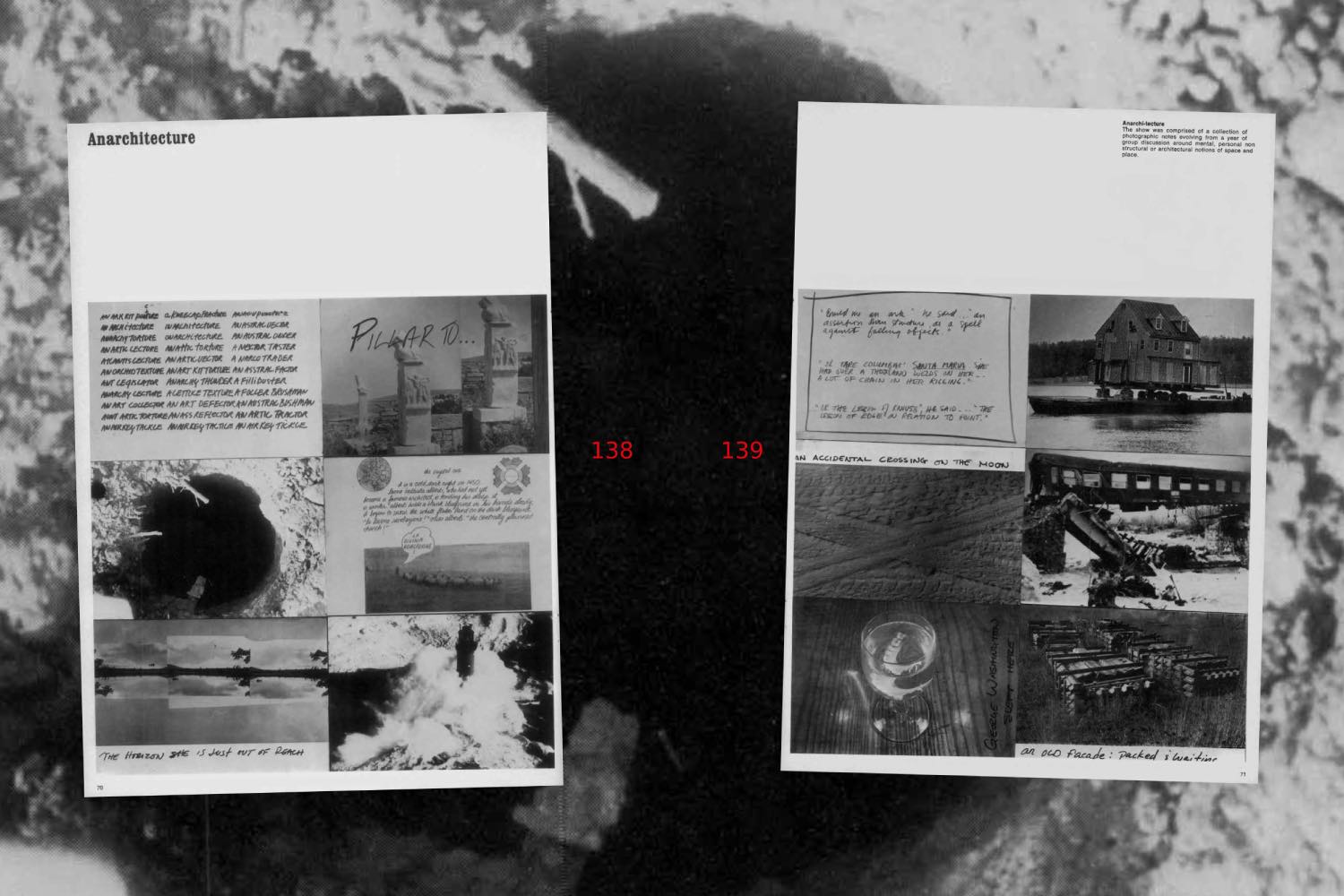

On the second floor, Energy Trees, sketched by Gordon Matta-Clark between 1972 and 1973, hangs in conversation with Gina Folly’s cynical photographs of cows raised in a solar-powered farm in Rotterdam. Folly captures their organs of production in closeup, distorting the lens of economic abstraction in which the cows find themselves, as further commodified by the promise of green infrastructure. Other models of systemic change are proposed by Ash Arder and Cannupa Hanska Luger — both repurposing short circuits into regeneration. As this exhibition extends to other locations in the city, the term “satellite” feels all the more literal; meanwhile, at the Swiss Institute, connectivity exceeds curatorial restraint: Arder’s refrigerator battery is powered by the solar panels in Haroon Mirza’s Oscillations for Caduceus (2024) on the roof, as if to reaffirm that “Energies” have to be considered in mass and (re)imagined in community.