St. Sebastian is a kinky pussyboy, or a honeytrap. Spank me, Blasphemy! Beamed into a bucolic, peachy saturnalia, his cock-ringed, handcuffed presence suggests appetencies are coming on, big and strong. Bleeding sweet from arrows and leveling off a tranquilizer’s lull, other smoldering hungers compete for satisfaction under this flaccid sunlight. The bare-assed archer, interjectional, might shoot again. The sky is a final rush of tender translucence. The saint’s jaundiced eyes, drearier than the teeth of a cursory skull, offer a gaze ever so slightly askew — a gaze for you but which you can’t quite meet in the time of looking. The fetish-fabled grove of lusts, submissions, and lethargies that is Stanislava Kovalčíková’s St. Sebastian or the competition of sensibilities (2023) expresses nothing tight-lipped. Serving her moods with deluxe, scandalous touch, she takes decadence straight.

In the genuine fortitude of this sub-boy saint, I am reminded of Chris Kraus’s writing on Simone Weil: “She wants to lose herself in order to be larger than herself. A rhapsody of longing overtakes her. She wants to really see. Therefore, she’s a masochist.”1 With a fire in her eyes, Kovalčíková wants to really see: “It’s a hunt,” she says of painting, “a riveting chase towards the invisible.” Conceiving painting as a pact whose “fruit lays inside,” her vantage is the vast region of perceptions that simmers beneath brain-rotted surface consciousness. Her tough-love figures resist the techno-objectification of porno-capitalism, though they might give a sickle-moon-smirk for the camera. Exerting the psychosomatic energy required to make an image, Kovalčíková paints out experience, externalizing realities as visions to “locate” a grisly, anguished yet metaphysical Beyond. Rising from “deep degrees of imagination […] like deep-sea creatures,” her frilled shark grotesqueries collapse the bullshit and wonder of life on this broiling marble. Admiring repulsion even as a potential aesthetic mode, veneration and abjection are whirled through a brute pleasure dome of feeling. In their voluptuary amorality and blissed out detachment, these are images deliciously twisted — orgasmic even. Carousels of expressions flicker with maddened glints of eyes and teeth as they surge with rapturous glee through big-mood entropy. Surfaces streaked in foils induce an inward gaze while confronting the monstrosity of selfhood breaking out of its confines. Twitchy looks see that you are implicated in this invocation of androgynes, creatures, lovers, centaurs, saints, cadavers, mothers, as if you, too, are summoned by the painting for morbid fascination. Any idea of identity will, henceforth, suspire a fetid air and be followed by a shot of satire and a suspect glimmer in the whites of the eyes. This mayhem has its own glory but is never grandiose. Sovereignty is found in alienation (which, as we know, is the first site of recognition) as the transcendental becomes a possessed, embodied affair.

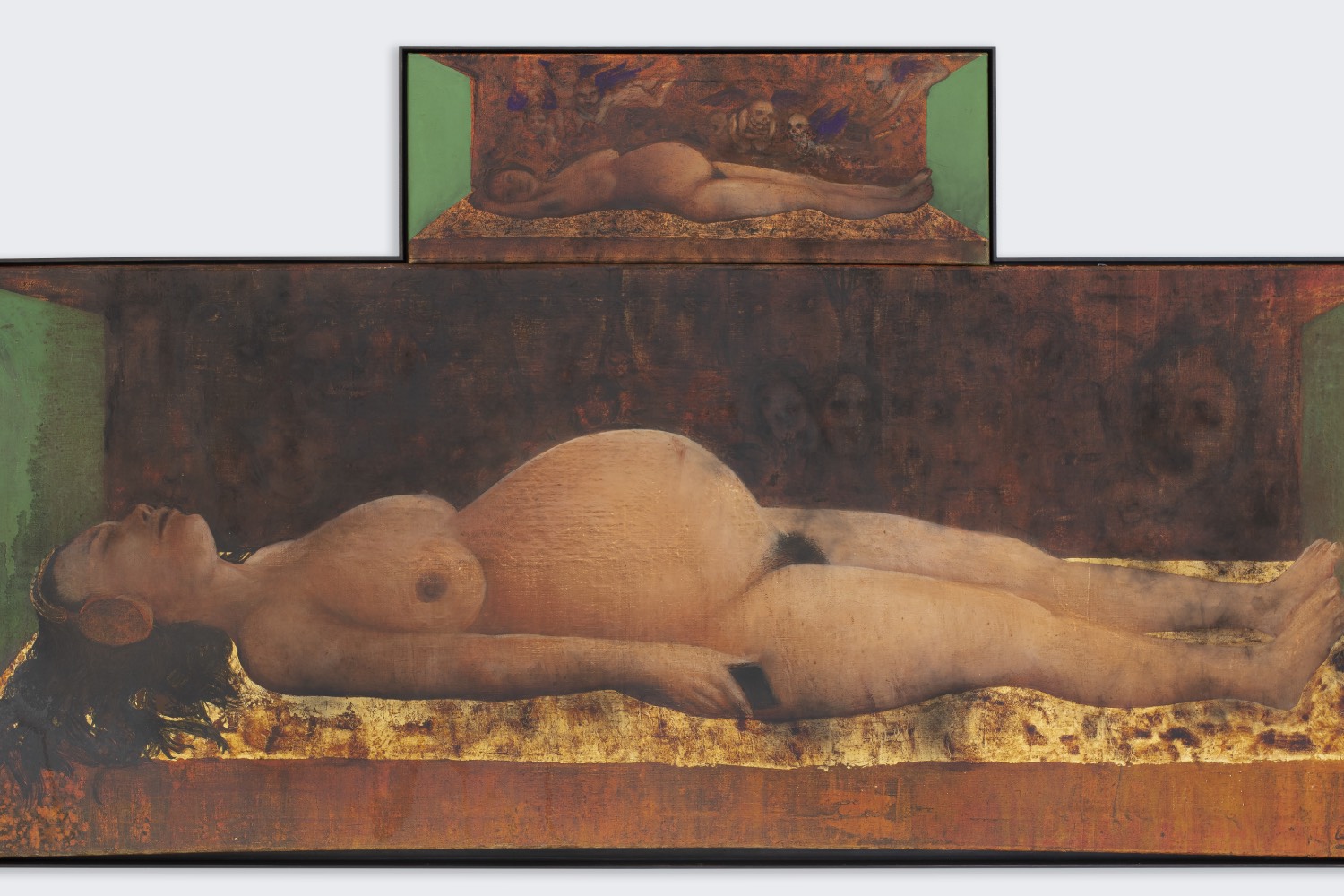

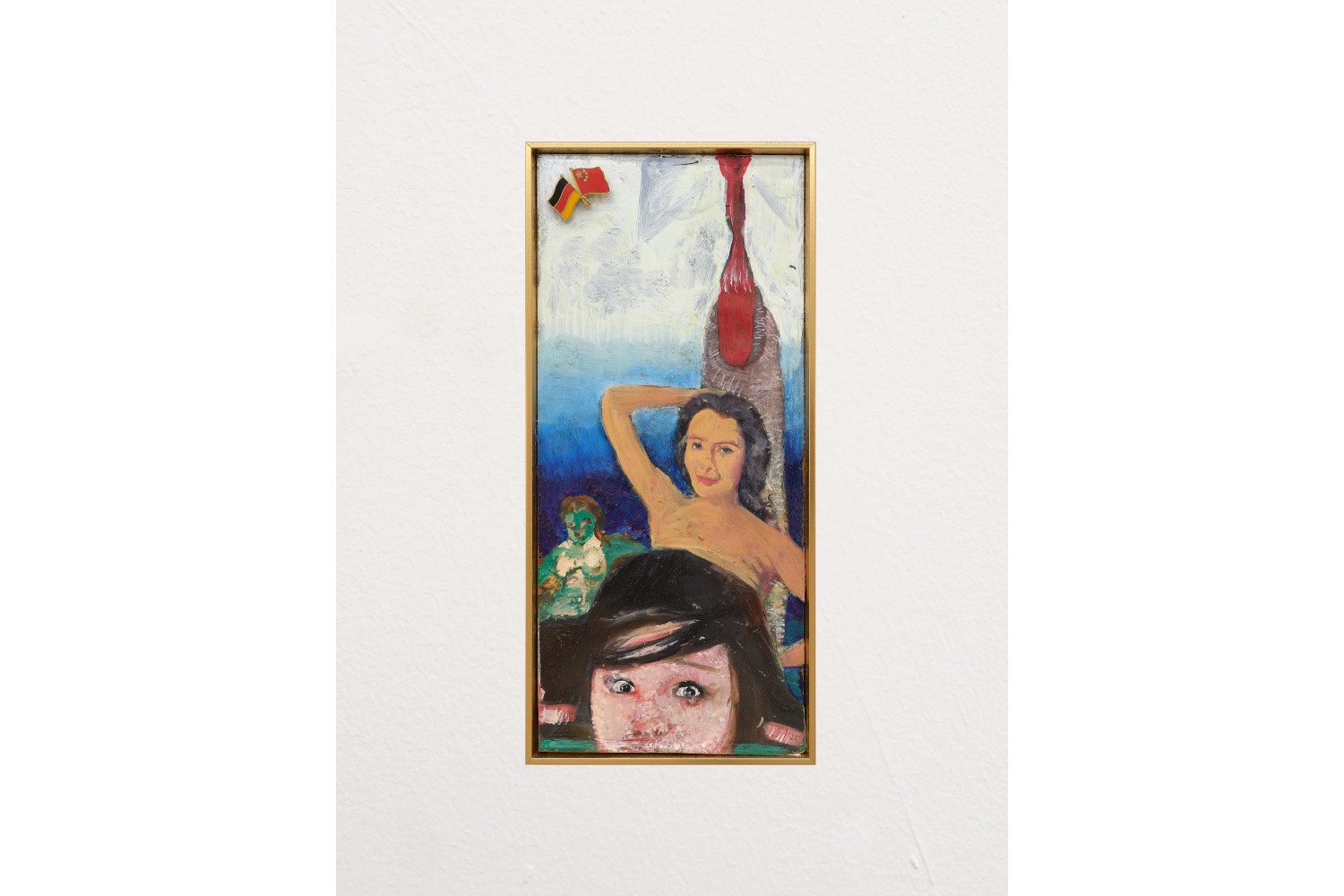

She’s a Venus in goblin mode. Basking with amphibian stagnancy, legs spread, this gangrenous gutter goddess stews in the armpit of a gnarled tree, a pet skull at her crotch. Yankee Venus (2023) is easy with her bastardized lot, compared to her other, more legendary incarnation. This reprise of mythos sure got ditched in the shit, yet, semi-divine, she is chill. Kovalčíková’s hyperreal, primordial, and metaphysical indelicacies trade in the modernist tradition in its most pervious sense, her purloined fire ensouling her paintings with glowering ironies and thrilling perversities. See, for instance, the Janus-faced nude of Misty (Foggy) (2017) that side-eyes Manet’s Olympia (1863), and the Sad Venus (2015–22) who knows the seductions of what is invisible in Velázquez’s “original” image (spoiler: she holds her own mirror). Notice her steely meditations on the female nude in moribund painting (Not dead yet, 2022; Panik im Park, 2020) wherein writhen postures are made fiercely avoidant of scopic violences. Her copper plate portraits are, too, faceted with myriad expressions: Käthe Kollwitz’s stricken severity and Paula Modersohn-Becker’s veiled stolidity; John D. Graham’s maniacal glares and Cranach’s squinty cynicisms. Elsewhere, multipanels and checkered grids share the geometry of medieval perspective while intricate skins are set into sfumato miasmas, phosphorous blues, bay leaf greens, antique metallics, and storm-of-Jupiter climates. As Kovalčíková moves closer to the inaccessibility of our own time by contemporizing art-historical quotations, painting becomes a liberal continuum of self and surface. The detournement of her vampiric resuscitations and promethean appropriations makes these images fuller and richer, flexing them into sensuous presences. Yet, these canonized excerpts still retain a sphixny coding that, like the sun, can only be witnessed indirectly.

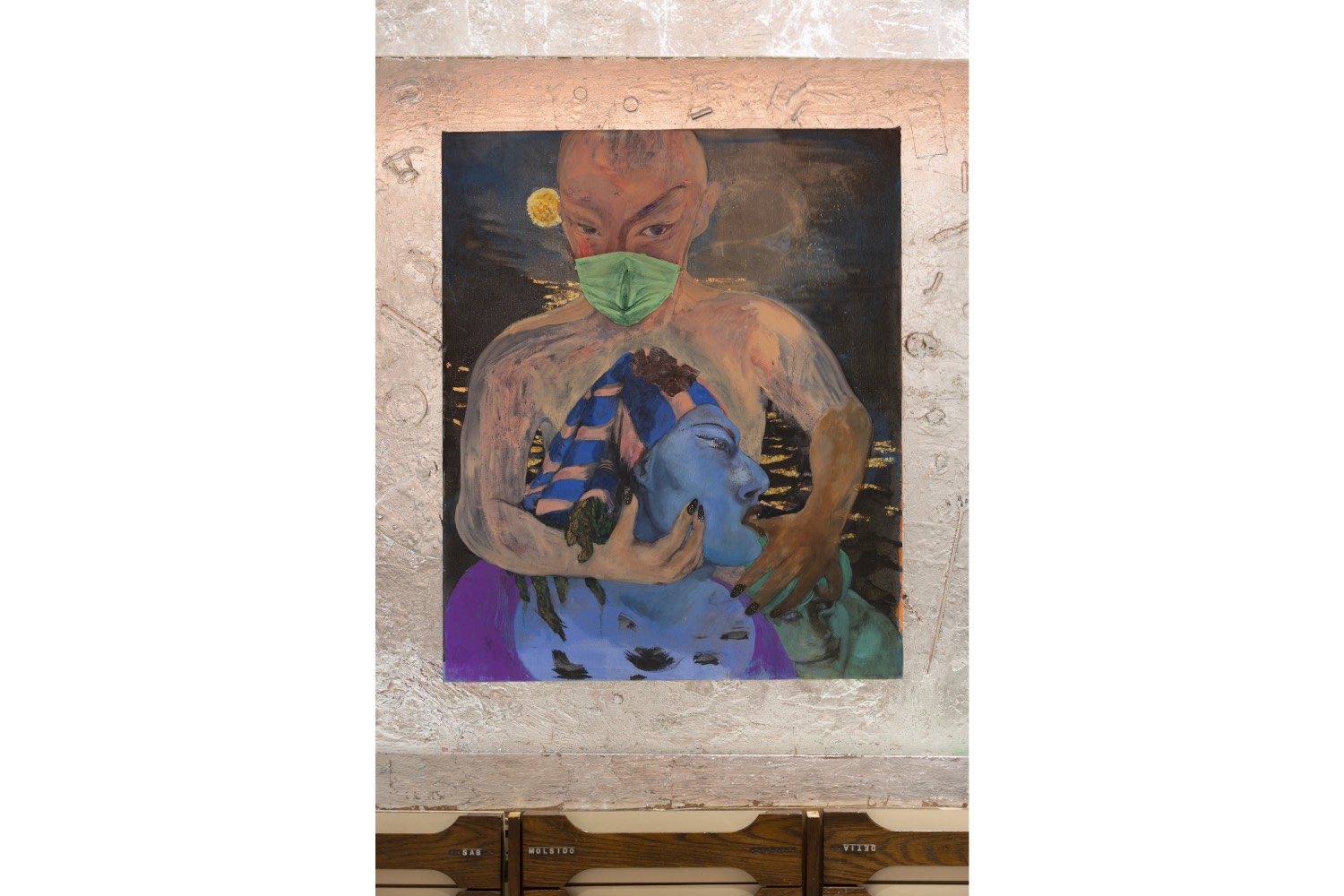

Swelling to the surface with the heat of corporeal knowledge, her paintings carry mythographic imagination as much as an insistence on the body. Yet her deeply intimate work, dark and salty, disinclines personal confession or revelation to an elsewhere that is somehow still contained in the work. Born in Czechoslovakia, just before the Velvet Revolution dismantled the Communist regime in 1989, the trailing presence of estrangement is a guiding star that contours Kovalčíková’s bodies. In fact, from supernova explosions to stellar winds, we owe our very bones and blood to stardust. As the preternatural is brought into a full-figured and warm-blooded Earth, Kovalčíková awakens sensation, that sweet spot where the grip of the Real is tempered of purchase and displaced as phantom. If anything, hers is a supra-real realism whereby, I’d argue, edgy theatrics allow the sheer pain and pleasure of reality to be apprehended at all. Insuppressible carnality is bedded into painting that greets demonic invocation as much as a hellish droplet of nail varnish (Manikura, 2023); tears of gold as much as a necrophiliac kiss (End of Old Times, 2023). “I love the alien in people,” she says, “god, I love the wildness, the wit, the lightning of the other mind.” That unholy “god” says everything.

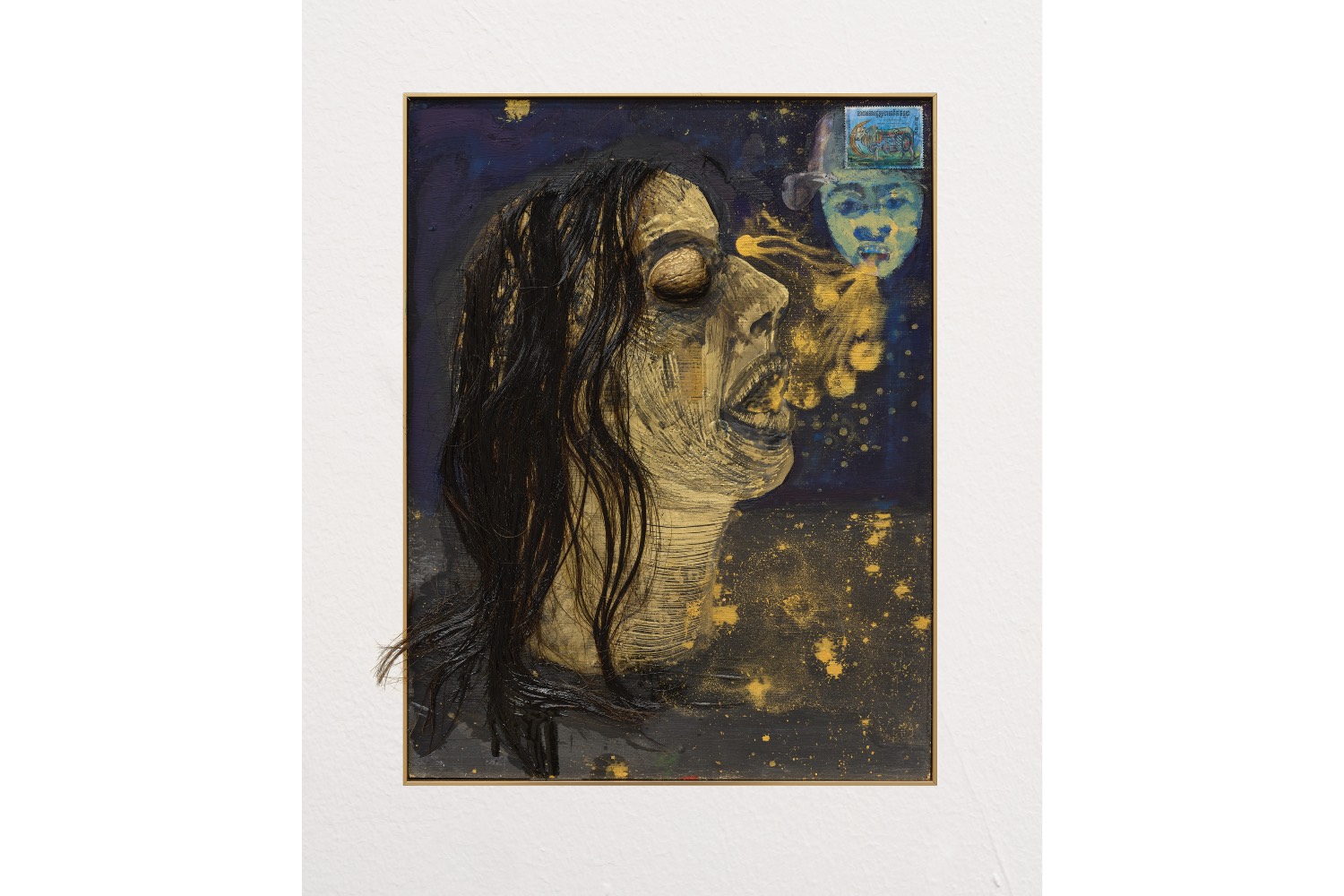

Spilled from spells and Freudian fever dreams, these fleshly spoils are indeed playing games of God. This knife-edge running of potency and solemnity, possibility and foreboding, is caused less by wild abandon than by keen discipline. Often worked from layers of molding paste, her paintings are birthed from an amniotic goop, as if the vying drives of her figures sought to rupture the already aggravated surface. Gestating for sometimes as long as five or ten years, paintings arrive after great deliberation, and bear all their residual enigmas as if freshly disinterred. Through a process that carves away self and narrative, these paintings materialize blistering gravities and ecstasies through emergent underpainting, moldering surfaces, and scabrous granularity. With the crumbling shimmer of gold, foil, hair, latex, coins, beeswax, dried orchid, or fried egg, this excremental craquelure, larded with bits, wields the mineral qualities of auriferous rocks, spores of rust, or wyvern breaths. These relics, skinned with time-warped patina and blitzed by experience, evoke a strain of wonderment that suits our ruinous contemporary. Which is to say, these are paintings trolling the contemporary as always already figuration. Indeed, anachronism or untimeliness may be the only way of attuning to a contemporaneity that’s adrift in multiple tenses.

In Abduction of Europe (2023), the Greek princess literally takes the bull by the horns. Screwing Zeus’s plot and seeking her revenge, she careens down a scorched highway littered with bodies baked in peach-fuzz light. Brandishing the behemoth with a lipsticked kiss, Europa prevails, rampant astride her renegade beast. As though to amplify the inviolability of this newly oiled allegory and its zealous, unassailable protagonist, the painting, exhibited in her 2023 show “First Rays of the New Sun” at Antenna Space, Shanghai, was installed behind one of two curved walls. These ensconced the large-scale paintings upon mirrored floors with viewership distanced and modulated through narrow horizontal apertures. The interior walls, paneled with gold sheeting, cast a lustrous grind, resulting in an atmospheric equivalence with the hushed brilliance of byzantine mosaics or else serving to fortify the paintings’ crepuscular antics. Under a hardcore gradient potent with twilit mood, schlubby anti-heroes crawl out of grassland in Das Goldene Kalb/Lascaux (2023). Demystified and wormy, they fumble about on all fours in a blundering want for purpose. Conjured from the deep deposits of the Lascaux cave and its magnificent roiling bulls, the animal consciousness of this titular golden calf is lavished. A manner of creation that verges on the creaturely, these luxuriant doses are conveyors of “aliveness,” however grotesque they may or must be.

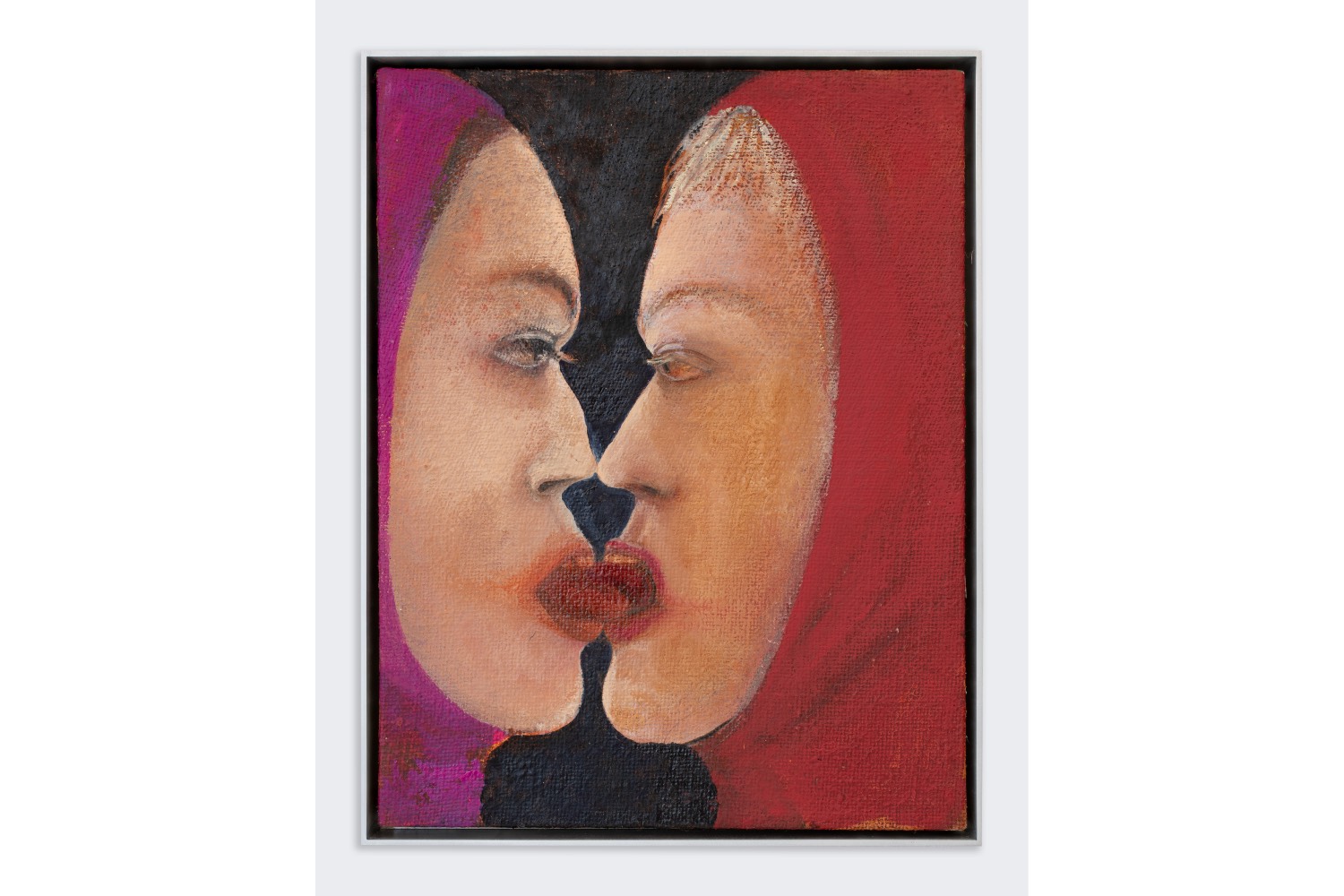

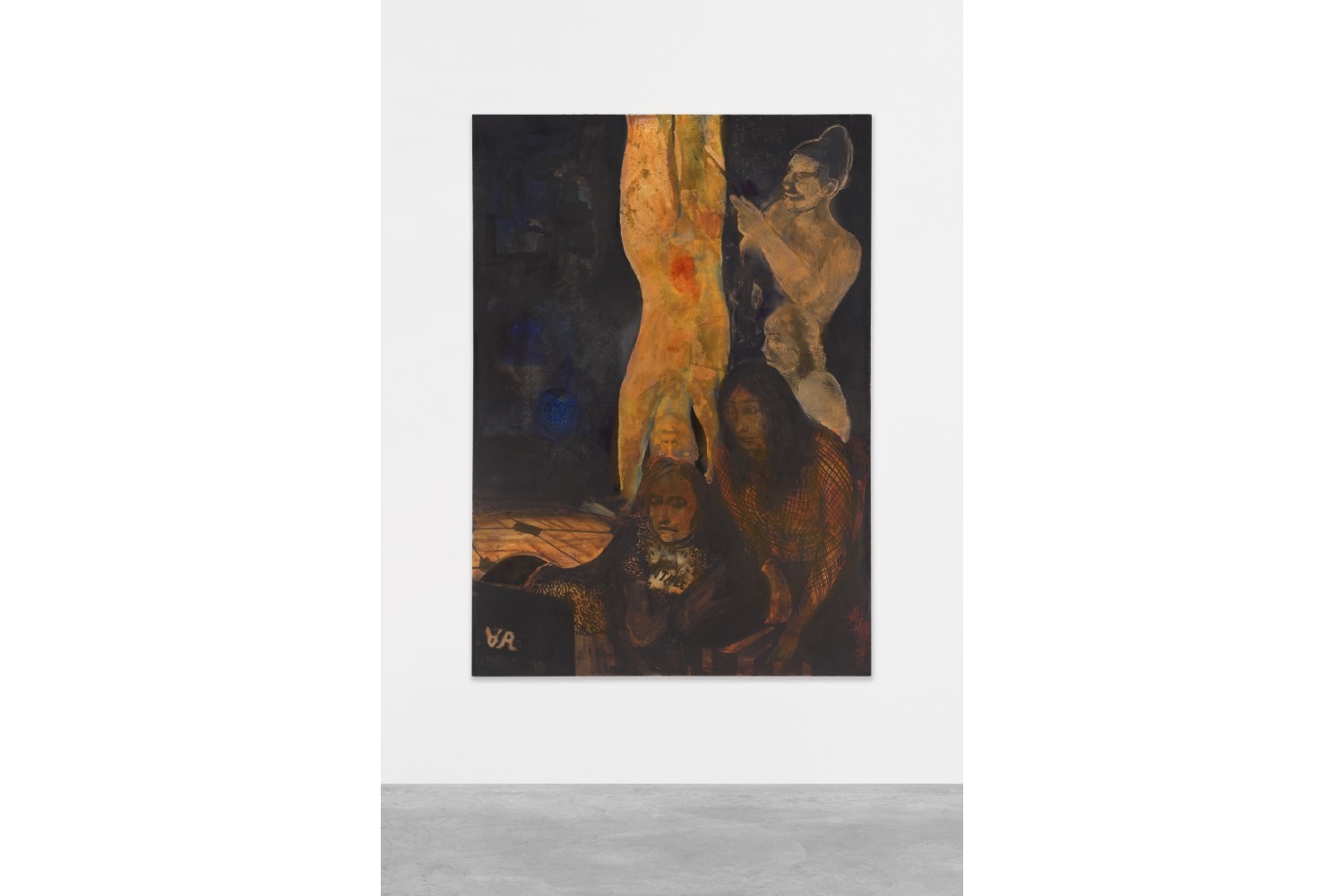

In A Lover’s Discourse (1977), Roland Barthes writes of the impossibility of drawing the primeval hermaphrodite, that figure of “‘ancient unity of which the desire and the pursuit constitute what we call love,’ is beyond my figuration; or at least all I could achieve is a monstrous, grotesque, improbable body.”2 The Ensorian pageantries of bodies, faces, and skins — so often trespassed or tautological — are the beloved wellsprings of Kovalčíková’s improbabilities, doubleness rippling within. Predicated on isolation, the methodological loneliness of her meditative process surely conjures an excess of self, causing so many spirits to interfere with reciprocal parasitism on the canvas. In Afterhour (2015–20), topographies of tenderized bodies are slumped, thick with seductions. See in Smear (2022) an erogenous interzone of muddled tongues twirling a bloodied Gordian knot, the two portraits recalling the balaclava profile of Odilon Redon’s Armor (1891). Yet her figures are also at times stilled by solitude, parenthetical like planets deprived of atmosphere. In Never Afraid after Dark (2014–20), a hanging torso (lifted from Titian’s The Flaying of Marsyas, 1570–76) is of limited interest to the four figures who surround the seemingly domestic bloodletting in a superposed fashion: no touch in sight. With a paucity of action here and elsewhere, Kovalčíková’s meteorology of social tension is an agent for turbulent yet often unseen influences.

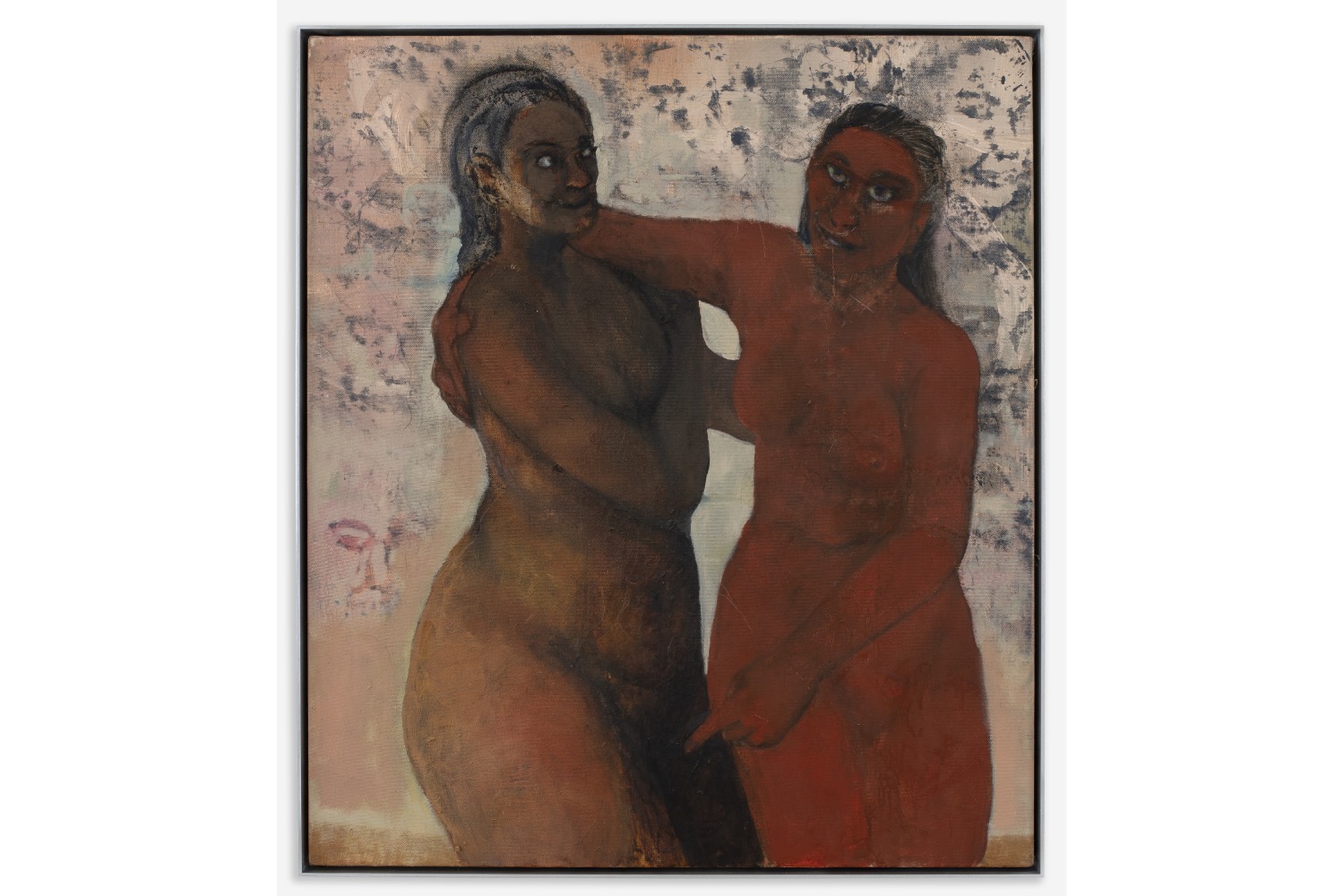

In this sinkhole we call the now, habit has surely dulled almost any recognition of how gross and fantastic interpersonal dynamics are. Kovalčíková restores those thunderclaps of experience with bit-lip ardency; her figures stoke their cindered netherworlds with hedonistic delights of all things freak. And it hurts so good. In her 2022 exhibition “Grotto” at Belvedere 21, Vienna, time was arrested with an amberous twist. A libidinous break, a post-doom dungeon, a beating furnace, Kovalčíková’s grotto is pregnant with the capacity for change. The sensate warmth, created by windows sheathed in orange film, the walls and floor shaded umber, established a cocoon of purgatorial brown noise. Nested therein are unearthly vignettes of psychosexual escapades whose morals are loosed. See the sugarplum purples that mellow the come-hither fondness of a gender-blended demimonde in Wait till the sun shines (2022). With gazes stoned on time, theirs is a histrionics of body language; just look at that tidal spine. In Double Venus (2019) a pair of zaftig figures partly embrace, one pointing to another’s vulva, while snickering faces form a mottled scrim of virulent black mold. Dripping in doomsday orange, the noxious mackerel sky of the three-paneled panorama Die Gute Hirtin (2022) mantles a peaty glade strewn with white goats, nude figures, and a faun. In this brightly strange Arcadia, blessed with two suns and studded with wind turbines, a horned figure soaks in a bog of hot chroma while another employs the mask of a goat’s skull. Naked torsos perform a bacchanalia but, in truth, they seem to bear deeper relation to their own psychological dramas, like Bellini saints. Nearby, a shaded voyeur rests, legs sprouting a goatish fleece. These opulent transmogrifications understand that the body is always an allegory, but, contextualized within earthly afflictions and sufferings, these gearshifts into the grotesque offer silvered exits to think through and beyond oneself.

Darting to the bittersweet heart, I find that Kovalčíková is doing love’s work. When her paintings aren’t looking back at us, they’re looking at themselves with our eyes, witnessing selfhood confront itself. These intra-, inter-, and extra- subjectivities show us something about losing one’s bearings and finding them outside of one’s body, perhaps in another’s eyes. Returning to Kraus, she writes: “Emotion is a current that dissolves the boundaries of a person’s subjectivity. It is a country. Shouldn’t it be possible to leave the body? Is it wrong to even try?”3 Kovalčíková takes a stab on the wings of emotions that return us to the lifeblood of supernovas. An infinite decreation of birth and decay, these little miracles of death drives and ecstatic pulses affirm that such an endeavor is never wrong and that unadulterated expression, forever hallucinated and mutilated, is the real language of love.