On top of a gorgeous hangover, Sophie Jung had no clean clothes, so she rocked up looking like shit, quite frankly. Burnt orange never was her color, but she persisted as she did, living on the turnpike of discouragement. Her regime was unhygienic, which was the main thing. Jung had been seeing two Jungian psychoanalysts and was on the fox hunt for a third. She’d tell her analysts different things, depending on her mood, which personality would go that day, and cry every third session to keep her health insurance on board. I sat listening to her latest bathetic breakdown wearing her Fresh Prince of Bel-Air Get-Up that wasn’t fresh; what is female friendship if not constant amateurish psychoanalysis? Jung started with miserable evangelical reserves, popping Adderall when she knew people were looking:

“So I said to my analyst — I said, don’t you think doc, given my meager improvement, I might resume affection for my mother?”

I listened like a reluctant Freud, combining some cursory knowledge of Jung and Lacan, slapping something together that resembled a response:

“Well, I think you’re wonderful!”

This bit of the story is true, just not the rest; Sophie Jung doesn’t even drink, though I stand by the burnt orange comment. Jung is an artist leaning into humor, slapstick, and theatrical worlds like the daughter of actors, playing up on double entendres and repartee to examine re/re/representation and the silencing that comes from psychic foreclosure. In particular, her practice has honed in on sculpture in the last three years. I wanted to emulate Jung’s wordplay by doubling down on the whole surname/Jungian analyst thing, which probably failed, but imitation is the highest form of flattery, no? Even her awards double down on doubling up: winner of the Swiss Art Awards (2016), Manor Art Prize Basel (2018), and Swiss Art Awards (2019). She’s a bad, bad bitch.

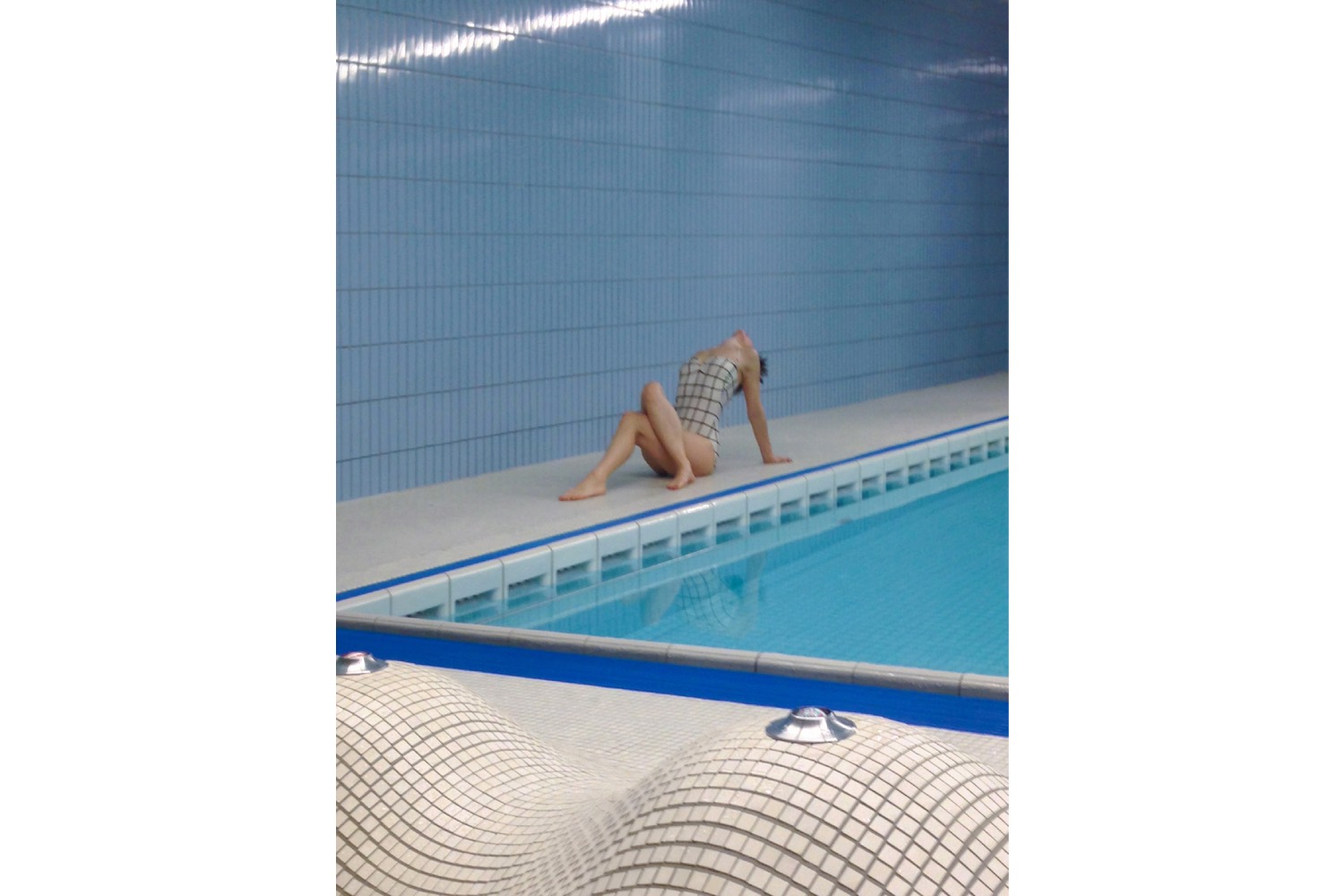

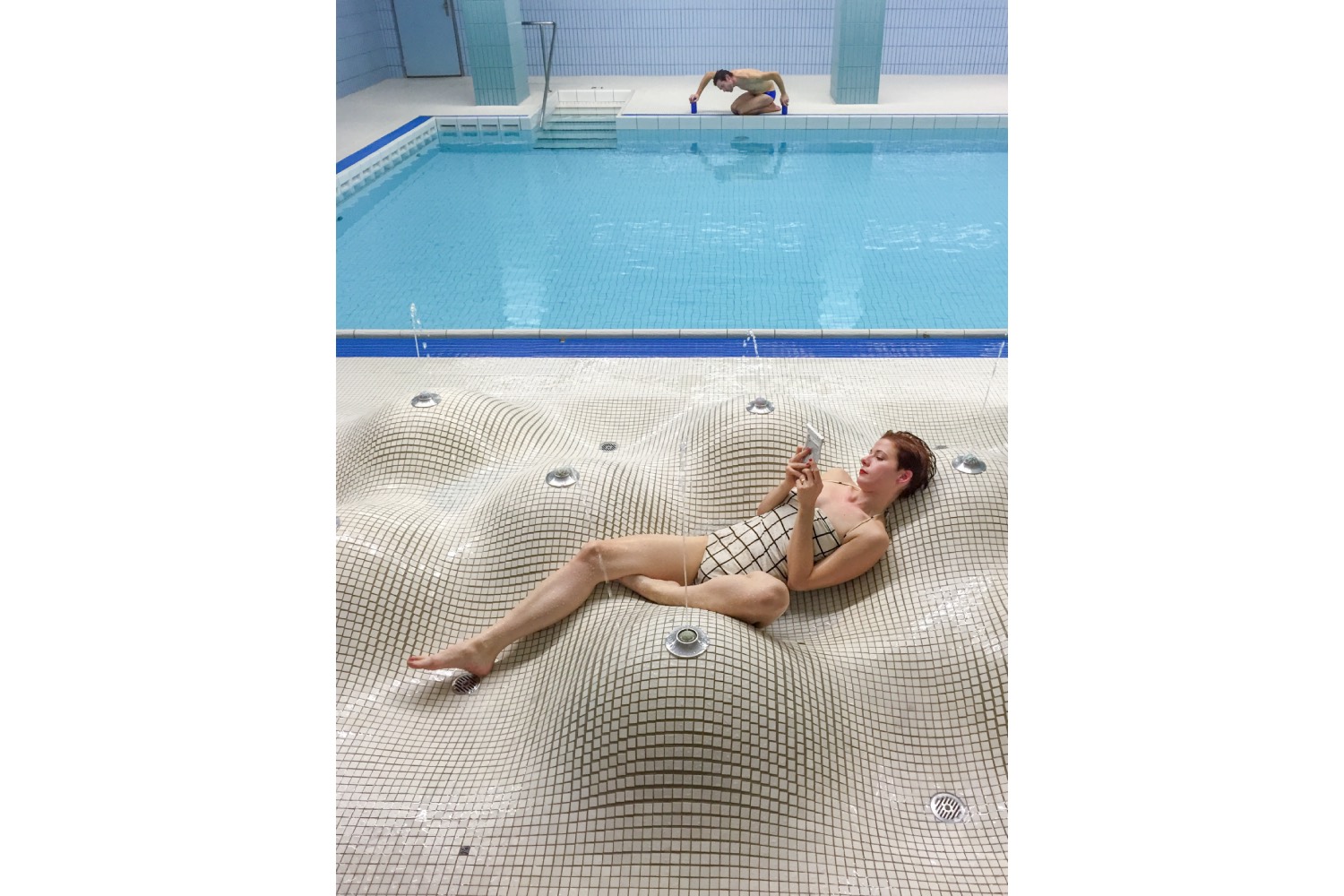

Word paronyms echo in her texts, performances, installations, and videos, among them her version of Ovid’s mythological Echo and Narcissus: Echo, the chatty nymphet, was punished by Juno into repeating the last words of other people. Eh, co? Nah, cis. Us! (2015) was a comic performance at Kunsthalle Basel, dipped in chlorine brine, bouncy acoustics, and preppy-pretty-boy Narcissus wearing blue speedos with some colossal shape. The actor playing the role spent the performance checking out his smokin’ hot reflection in a swimming pool, disinterested in anything but his perfect (probably Danish) jawline. Audience members entered the space in bathers or bathrobes, Celine Dion’s power chords blasting in the swimming hall (kill me), ricocheting off tiles and fountain mounds where Jung sprawled in a checkered one-piece, reading Ovid’s original on an e-reader: Echo the Pre-Raphaelite waif falls head-over-heals for Narcissus and his personality disorder(s), but Juno’s verbal curse makes it impossible to call to him, beckon him in a telephone-sex whisper: What are you wearing?

As gorgeous as Narcissus is, as infatuated and alluring as Echo becomes, Jung’s farcical version of Roman mythology is filled with rage. Jung earns her artistic stripes via hilarious diatribe, asking the viewer to strain neurons away from jaw structures, battle tinnitus (both lousy varieties), and realize Ovid’s Metamorphoses is pitifully, chronically reductive. The expert of hexameter reduced to pervert, hexed amateur. (Yeah, yeah, terrible pun, but it was that or rhyme with Narcissus.) Why have we not seen it before? Echo, a water sylph with an agile tongue, admired for her magnificent voice and oral, I mean oration, a fabulous singer giving Celine Dion a run for her money (not hard, I guess), is ultimately silenced. The 1700s was a shit-hot century for clamming up women. Meanwhile, Narcissus invents, nay, reinforces the sublime stage for a man who is captivated by himself, unable to listen to anybody else — business as usual. Jung isn’t ignorant of this repetitive, sneering sketch, using a potluck of humor, cutie-pie 1950s swimsuits, cheap lyrics, and scantily clad viewers to writhe incautiously over fucked-up iterations of sexism and patriarchal vanity. Rage: why should it be antithetical to humor?

Jung’s is an undistracted aesthetic disturbance bordering on psychic collapse: truly perverse humor under respectable appearances. Is this the only thing she’s angry about? Hardly. She’s been on that analyst’s coach for an undefined period. Crude, violent emotion manifested comedically in “To Do Without So Much Mythology” (2021) at Galerie Martin Janda for curated by (14th edition, 2021). The theme that year? COMEDY! I would know; I wrote the festival text. It was about jokes, blue-neon signs of overworked sex shops, landscaping, and circus clowns, so, mostly about Donald Trump.

In her sculpture The Queen (2020), the artist neuters a hyena and sweetens the conflict with infinite perversity and, I might add, animal cruelty, which she’s very much against. But this aspect of “cruelty” allows the audience to browse through her image reservoir of dandy fabrics, a Victorian-era skirt raised 2.7 meters, held up by the taxidermized tail of a desert hyena — we can peek up her bloomers like degenerates, jam in a quick, rough Pap smear with metal barbeque tongs. The phallic tail scurries up the garment pell-mell, sourcing immense, depraved pleasure in the queen’s bodice, her royal waist cinched to malfunctioning proportions. Eating is overrated. The smaller her waist, the shallower her breathing, the higher the status is the general rule of thumb; violated breatharian queens live on measly air proportions and the occasional packet of Sweet’N Low. Besides, what woman needs a liver? Hyenas are shifty predators, not scavengers, and although the installation is initially parodic and a little dubious, Jung never succumbs entirely to the comedy theme. Is this a good idea? It’s an idea. The sculpture is unsubtle, the comical that does not make us laugh, and is nearly untenable for respectable discourse: nonconsensual garment gapes, the panic of visibility, cervical catastrophes, broken Hippocratic Oaths of non-maleficence, archaic procedures in a waistline islet striptease. Out damned spot! What Jung and her heinous highness desire beyond flourishing send-ups is to remind us of the backstage ghosts spotted and blotted out: disappearing women, quite literally. Which is all to say, not taking things too seriously in order to take them seriously.

Hélène Cixous swooned at good appetites and larger portions in her 1998 book Stigmata: Escaping Texts. She loves eating out, so I’m told. “I beg you, eat me up. Want me down to the marrow.”1

Jung’s been devouring Cixous’s vital literary marrow for years, the petit fours of écriture féminine that grows her as big as an uncastrated stallion. (For the uninitiated, écriture féminine is uncooperative women’s writing that deviates from the traditional masculine writing styles. Anything with the word women in it mostly goes unnoticed). Radically reimagining the role of sitcom gags, feminist methodologies, cliché, overkill, roadkill, hypocrisy, and perhaps, ultimately, the unresolvedness of rage is a bad-tempered condition she scrutinizes in words.

Funny texts and droll, snappy lines create an artistic torpor, fighting against hegemony. In his book The Pleasure of the Text (1975), Ivy League goody-goody Roland Barthes prattles on about prattling on (like it’s a bad thing, pfft), and tmesis, which I had to Google Dictionary since I went to public school next to a sewerage plant. Tmesis: (noun) word compounds jammed together with hyphens. E.g., un-freaking-believable. For The Bigger Sleep at Kunstmuseum Basel (2019), Jung rolls in the stigmata’d mud of interminable prattling, using her wit and forked tongue in sharp blasts of cynical crucifixion: an indulgence of which Cixous would very much approve. Performing the cliché role of the hysterical, maniacal woman (à la panicky Zelda Fitzgerald) spurting out ad-libbed, so-bad-they’re-good puns and riffs, Jung commands James, the black-suited butler, around the room while laying prostrate on her designer chaise lounge. (It’s gotta be a dupe on an artist’s wage.) James flits about moronically, making Belgium waffles for the audience, failing to keep up with her shifting, battered, half-ethical demands — she’s tangential, there’s no doubt about it. Let-them-eat-cake vibes reverberate off museum walls in dehumanizing clang associations, breaking the fourth wall to castigate the butler in Brechtian asides: “He’s cute but incompetent.”

The Bigger Sleep turns incessant, demeaning babble into blissful re-representation, whereby it attempts to overflow and break through the constraints of reductive, hysterical women narratives by embodying the cliché itself, and the risks of ideological imposture are thereby resolved. Deadpan and triumphant, draped in a slinky robe by Victoria’s Secret, she creates a second-degree reader who moves past the stories told repetitively in a well-spoken, straightforward way and reserves them until the text is her desired fetish object, her petite mort — she likes eating out too. “Feed them waffle, James, not the means of making waffle.” Jung’s character doesn’t mince words. She wants results! A plate of devouring commands reimagining Cixous’s pathological obsession with the sleepwalking politics of consumption: “There is no greater love than the love the wolf feels for the lamb-it-doesn’t-eat.”2 (There’s that private school tmesis again.) So, what do the flappable James and wolf represent? What restraint are Cixous and Jung asking of them, of us? Which lambs are sacrificed when feeding on ruinous altars of stigmatic beliefs? Questions she trusts to her audience but probably shouldn’t. The text itself is atopic, if not in its consumption, at least in its production. Rabid, paranoid, waffling on rousing overslept representations and gendered servitude, and this humorous purge, this reversed defection, is a signifier of rage, rage, rage. My god, what are all these silly women so angry about?!!

Back at it, Jung pokes and prods around in Wonderland-inducing aesthetic erethism (aka mad hatter disease… had to google this also): an unusual or excessive response or irritability by the whole, frantic nervous system. Erethism is characterized by behavioral changes, including irritability, depression, tremors, anger, disorganized speech, and even top-of-the-line delirium. The symptomology reads like a textbook pathology of women’s “hysteria”; it’s probably still listed in the DSM-5. Idiotic blushes, ravenous Victoria’s Angels, and stammering women in Jung’s hol(e)y hands experience sudden obliteration: the upper-middle-class masculine values of bronco warriors find an enduring desquamation through the artist’s heckles, suspension of heart, and all the sickly waffles of subjugation we’ve long been told to eat. Jung and Cixous: total power couple. Reclining on an analyst’s couch, velvet chaise in girly pink, she angers our nervous system with the electric shock therapy of artistic deviancy, refusing to wolf down the myth of women without a voice or shadow. An echolalian oeuvre with horsepower on its side, ruling the life of rage with humor, devouring archaic representation and all the warrior narratives therein.

Bite me.