An extremely loud, happy-hardcore remix of a cult classic by Russian suicidal-psychedelic-punk-band Grazhdanskaya Oborona (Civil Defense) animates the dance floor. Through the dimly lit setting I witness a blur of Air Max sneakers, black sport trousers and blazers in acidic colors. Everyone is jumping in place like an impromptu CrossFit session. Bang bang bang, w-e-e-e! This is Skotoboinya (Slaughterhouse), described to me as a “kinda underground” party. As a constant seeker of something new on the Russian independent scene, I was interested to see what happens when a bunch of sixteen-year-old boys and girls try to reproduce early ’90s Dutch rave stereotypes in the midst of Putin’s Russia in 2016.

An extremely loud, happy-hardcore remix of a cult classic by Russian suicidal-psychedelic-punk-band Grazhdanskaya Oborona (Civil Defense) animates the dance floor. Through the dimly lit setting I witness a blur of Air Max sneakers, black sport trousers and blazers in acidic colors. Everyone is jumping in place like an impromptu CrossFit session. Bang bang bang, w-e-e-e! This is Skotoboinya (Slaughterhouse), described to me as a “kinda underground” party. As a constant seeker of something new on the Russian independent scene, I was interested to see what happens when a bunch of sixteen-year-old boys and girls try to reproduce early ’90s Dutch rave stereotypes in the midst of Putin’s Russia in 2016.

One can book the best musicians, invite crowds of people, turn venues into wonderlands, but real energy is impossible to guarantee. It is either there or it is not. At Skotoboinya, it’s here and it’s raw, like a school disco on speed. Everyone is wound up, wired for sound, jumping, sweating and shouting; the kids radiate a vitality that justifies turning off the lights. It is midnight, too early to party in downtown Moscow, but this industrial warehouse is already overcrowded. I notice Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, former member of Pussy Riot, making her way to the bar, surveying the surrounding teenagers like a vampire. Next to me there is a kid with a 1993 picture of the burned façade of Moscow’s White House on his T-shirt. I ask him when he was born and he says, “2000.” That is telling. I start to realize that the hip ones at this party look exactly the same as the gopniks — the Russian chavs — of the small cities of my childhood in the mid-1990s, dressed derivatively yet more expensively. Blinded by the stroboscopic lights that suddenly irradiate the dance floor, I make my way out, crashing into a rude, pumped-up security man just as he is counting a huge bundle of money. He proceeds to deposit it into his barsetka — a type of belt bag also popular in the ’90s, but which, in his case, is an authentic reminder of a kind of gloomy criminal kitsch from that earlier period.

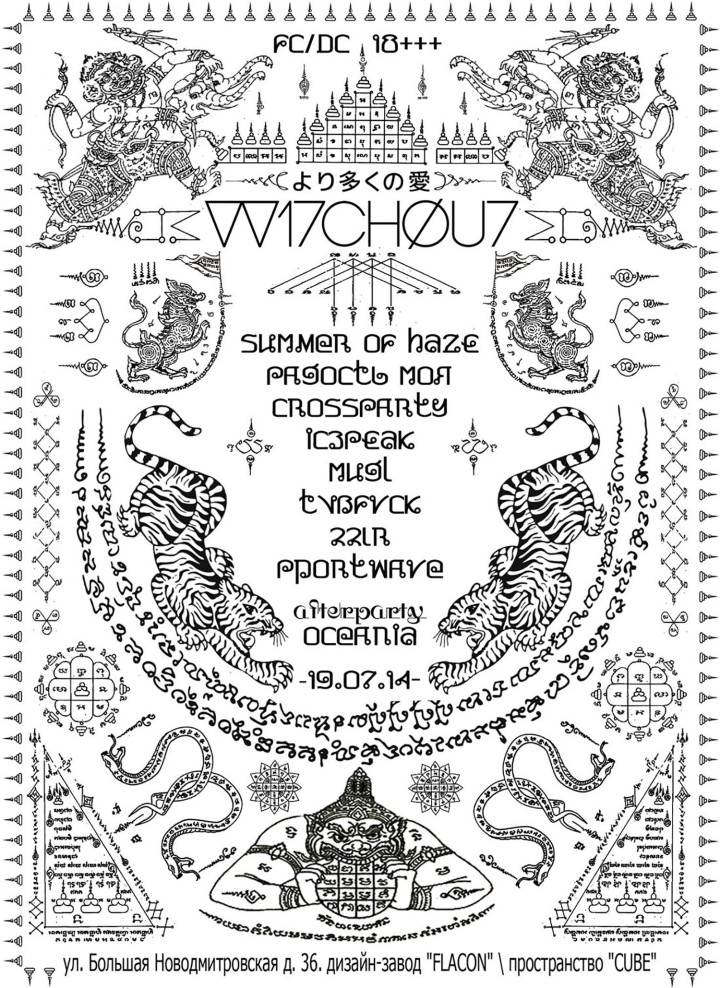

Skotoboinya is a spin-off of another series of parties, extremely popular among youngsters, called VV17CHØU7 (pronounced “Witchout”), where witch house electronic music is in favor. Witch house had a brief popularity in the United States, but it experienced a second life in Russia, where it is now bigger than ever.

The brains behind Skotoboinya and VV17CHØU7 are Kira Borisova, formerly an architect, and Victor Eroshenko, previously a writer for Russian television, neither of whom had much prior experience with club life or party planning before VV17CHØU7. For them it was more a one-off experiment — to see the kinds of people who would attend an event comprising independent musicians without connections to labels, artists whose CVs comprised SoundCloud and VK.com, the latter being the largest Russian social network, which won its local struggle with Facebook owing to petabytes of unlicensed content. Borisova once described how VV17CHØU7 grew out of VK, with its Tumblr-like aesthetic and rhizome of autogamous memes and music. In VK, as in certain postmodern cultural dimensions, there is no time — everything from the stylish retrofuturism of the ’80s to early ’90s nostalgia is combined in one continuous flow of images and sounds. The neocybergothic revival — with its love of pumping rhythms and EBM-like aggressive music combined with angst and despair — was so attractive to legions of melancholic, music-loving teenagers. Of course they joke about it, and numerous web pages now serve as forums for witch-house devotees to share memes. One such image shows a handshake with “suicide” written on the left hand and “me” on the right, with both pinned together by a witch-house-branded stapler. This particular brand of black humor — the dating web page is titled “HIV-infected dates” (“HIV” sounds like “witch” in Russian) — somehow reflects the post-ironic culture these club nights have tapped into.

As a youngster, melancholy and hedonism often go hand in hand; the lust for death is just another form of lust for life. VV17CHØU7 and Skotoboinya offer what both adults and teenagers crave, namely joy, and they do so in a very democratic manner. For example, VV17CHØU7 has an all-black dress code, but it doesn’t matter whether you are wearing prestigious brands like Kokon To Zai, or whether you’re sporting H&M or apparel borrowed from your parents (suggesting that nostalgia is often a longing for one’s parents’ past selves). The same is true of the music. There are almost no skills required to make witch house. Once I witnessed a Skotoboinya headliner called Gazovaya Eblya (Gaseous Fuck) play a track by Otto von Schirach with little recognizable remixing at all (probably he just hit “play” while surfing VK), yet none of the moshers on the dance floor seemed to notice. A Russian proverb comes to mind: “Take it easy and people will be drawn to you”

I’ve often wondered about the seeming Russian predisposition toward darker genres of music, a phenomenon that also extends to the old Soviet territories. No doubt its roots can be traced to the Russian folkloric tradition of ritual laments, but the late twentieth century also offers clues. From the mid-1990s such esoteric British groups as Coil and Current 93 were, for instance, much more popular in Russia than in the UK. I once met Mat Schulz, director of the Polish music festival Unsound, which hosts experimental artists from all over the world. He told me Eastern Europeans are interested in neofolk, dark ambient, industrial, dark techno and so on, like no one else. Likewise, Russia’s former Gauleiter of Kazan, a notorious member of National Bolshevism, now runs a company that organizes all kinds of “dark” events, from neofolk classics to modern cold wave and edgy industrial techno. From the ’80s hysteria for Depeche Mode, with people celebrating Dave Gahan’s birthday in Triumfalnaya Square (later the epicenter of Russian opposition) to the modern craze for all things neogothic, darkness is indeed our old friend.

Borisova and Eroshenko have called their company より多くの愛 , which roughly translates as “More than Love.” Likewise, the past few years have been a summer of love with respect to the growth in Russia of psychedelic drug use. “Grave raves” — a term often associated with VV17CHØU7 — are no exception. Thanks to TOR, i2p, PGP and other services with access to dark net markets, the spirit of Russian raves changed from its prior associations with amphetamine and vodka to many more kinds of psychonautic exploration. Despite police drug raids, which became commonplace this summer (the National Drug Agency has been deemed helpless in the face of modern technologies and has switched to old-school methods of search and seizure), attendees of より多くの愛 events are radically apolitical — they’re more interested in parties than in Party.

This autumn より多くの愛 has joined forces with Young Russia, gangs of cloud rappers (heavily inspired by Swedish Sad Boys demigod Yung Lean and his American spiritual brother Bones) and hip electronic label Hyperboloid to tour Russia with help from Adidas and Boiler Room. In nearly every city the shows have sold out. Ic3peak, another band whose profile has been raised by VV17CHØU7, is now touring the US. Borisova and Eroshenko have also revived the musical career of early-1990s pumping house duo XS Project, while being valorized in an exhibition about Russian rave culture at the Winzavod Center for Contemporary Art, titled “Svezhaya Krov” (Young Blood).

In under three years, より多くの愛 has ascended from an underground warehouse rave to a money-making machine adored by thousands of teenage cosplaying ravers, just as the older generation cosplays the Cold War. There is some strange logic to it: raves have often delighted in apocalypse, and they have found a home in modern Russia.