It’s a disturbing sight, at first: a person up against the wall of the ICA in Philadelphia, sniffing it. Then again, it’s also a disturbing smell — an olfactory artwork by Sissel Tolaas called Fear 21/21 (2021–22). This part of the building’s exterior, and a stairwell inside, are painted with a cream-colored scratch-and-sniff paint, developed by the artist to give off the smell of fear. Specifically, the paint emits a chemical cocktail derived by sampling and analyzing the sweat excreted by twenty-one frightened men.

This is how Tolaas works. When you think her art is too corny or dramatic, the hard science asserts itself; when the science gets too finicky, a dense, fragrant fog of metaphor descends to rescue the experience. But it’s not fragrance: Tolaas insists on the word “smell” over “odors” or “scents,” another attempt to pare back the poetry to an objective core. I guess this is how smell works. Scientists can synthesize the nose-triggering molecules in vanilla, but the precise mechanisms that unfold this smell into memory remain obscure. On the art side of things, too, there’s the odor of magic — a smelly work can transport us, or educate us, but the technique of turning fear into paint is practically alchemy.

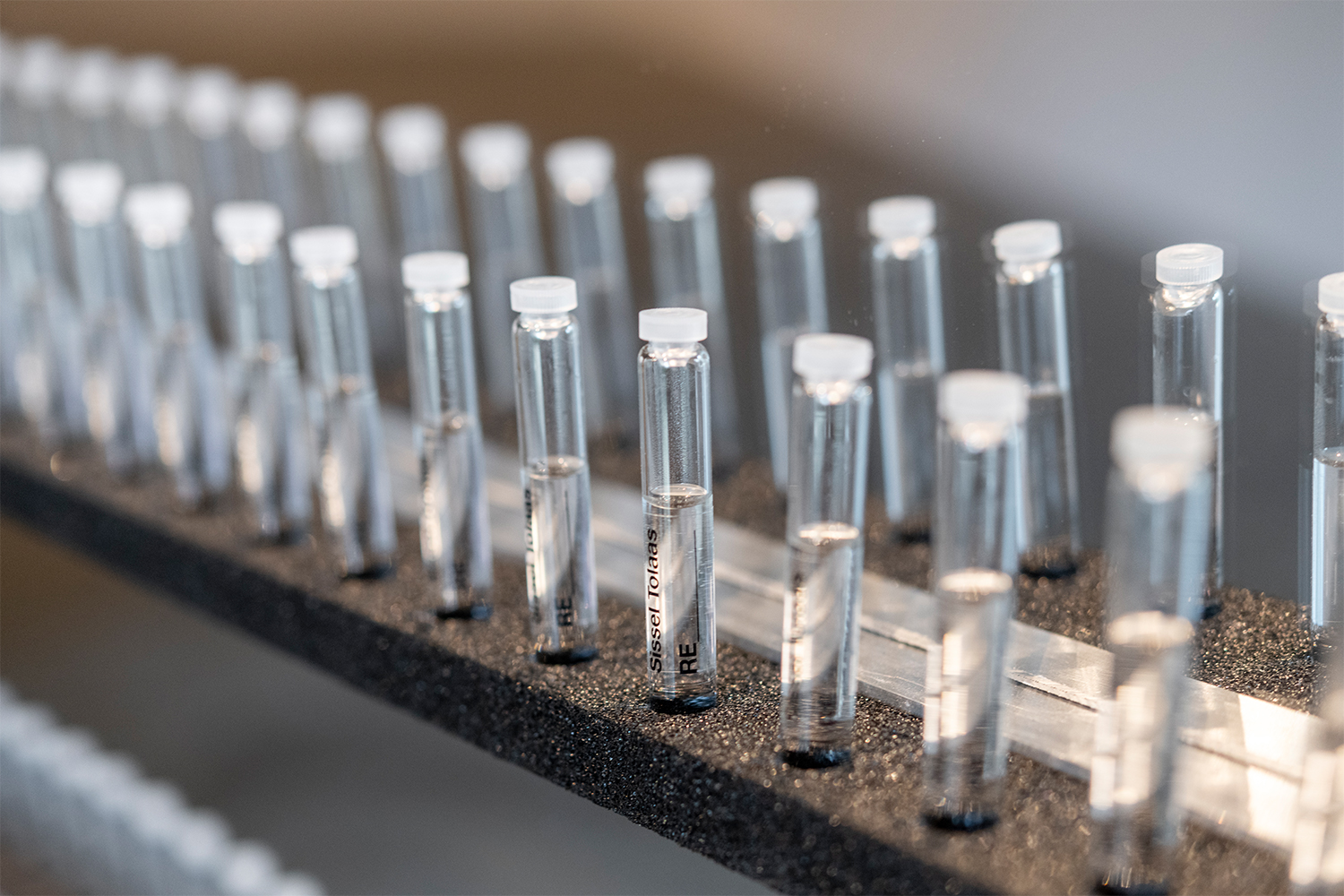

Tolaas’s museum-wide exhibition, titled “RE_________,” is goofy and poignant. Like a herd of bubbles grazing on the concrete floor, Still_A_Life (2020), comprises 365 glass ampules containing a single exhalation each, one allegedly made every day of 2020. Yes, breath is life. It’s death, too. In another room, D-earth (2022), an arboreal delta of black devices and cords, daisy-chained together like power strips under God’s desk, emits little puffs of decay. There’s universalism afoot. Certainly, some precepts of organic chemistry hold true across our species — if anything does — and most animals experience some degree of “smell.” Humans have around four hundred different kinds of smell receptors, roughly half as many as dogs and way fewer than elephants. Still, it’s patronizing to equate all human (or earthling) experience this way — the molecular signature of fear, for example, if Tolaas’s work is any guide, differs noticeably across twenty-one people.

Then, there is AirREborn BelowAbove (1994–2022) — a set of electric fans linked to real-time weather data and pointed at big blue-gray drapes. When the wind blows in Norway, the fans blow at the ICA. It’s a neat trick. It also exposes the wild faith in technology that undergirds Tolaas’s faith in biology — the utter equipment and money needed to generate these universal vibes.

Of course, money is no secret: the show’s mirrored title wall is lined with shelves of small glass vials of Liquid Money_1 (Ampoules) (2000–ongoing), the artist’s olfactory survey of the local currency wherever she exhibits. (Her first samples were Swiss francs.) As if to remind you what it’s all about — circulation, privilege, the universality of commerce or lack thereof? — visitors are invited to take a vial home. In the meantime, a clear pneumatic conduit of the sort that used to carry messages around banks and offices plunges in and out of the gallery walls. There’s another set of pipes, too — silvery ducts breaking through the wall and back under like a sandworm, carrying the smell of vanilla throughout the museum from puddles in little concrete berms on the ground floor. Vanilla is apparently the most popular smell on earth, for a simple, universal reason: vanillin occurs in breastmilk.

Tolaas offers wonder, without a cynical taint. Part of this comes from the sheer magnitude of the questions her work raises through our noses while our eyes may be desensitized to grandiose themes in art. There’s the problem of where (if?) art ends and the world begins. There’s the problem of a substrate, where even an abstract, molecular work of art nonetheless requires something like a canvas (an atomizer, a vial, or indeed paint) to deliver it.

There’s the problem of writing — of putting words to something for which, famously, there aren’t any. Instead, the scribe of smells resorts to comparisons: the Proustian jolt of bergamot and vanilla. Fear is sweet-smelling, almost floral; money, sharp and peppery, metallic. My notes for one of Tolaas’s concoctions read: “mud, bark, moss, wet forest, skunk, mud, soil, rot, bacteria.” Another prompted more idiosyncratic impressions, revealing my ’90s childhood in the United States: “ninja turtles, gak.” Under these conditions, it’s hard to keep universality in hand. It’s like saying we all know the experience of experiencing.

In the spirit of experiment, I regret foregoing SelfPortrait (2005– 2021): soap, placed in the museum restrooms, that smells like Tolaas. As for the vial of liquid money on my desk, I might dab a little on my wrists.