Simon Denny is one of the first established artists to engage with blockchain ideology, creating works that render visible the strategies and aesthetics of the technosphere. Through ambitious multimedia installations and now NFTs, Denny channels the insights of crypto’s prehistory into a critical vision for this precarious field.

Sonja Teszler: You once said that “the most fundamentally disruptive” aspect of the blockchain was its potential to “monetize the attention economy” through a “proliferation of tokens.” Has this happened in quite the way you anticipated?

Simon Denny: I’m not sure. I still think that when “likes” or some kind of equivalent attention metric become literally abstractable currency — through some kind of tokenized social network that one can use in ways that decentralized finance has normalized across the Ethereum network — it will be a very intense and different world. If I can leverage my attention to earn currency in a more direct framework than I do already, incentives and behaviors that get rewarded will be even further tethered to the kinds of markets we’re becoming more familiar with.

ST: Your 2015 exhibition “Products for Organising” and your contribution to the 56th Venice Biennale considered how technology affects the global economy through different forms of “hijacking” — from cryptocurrencies to hacks to data leaks. As “disruption” is assimilated within the grammar of technocapitalism, where do you see potential for hijacking right now?

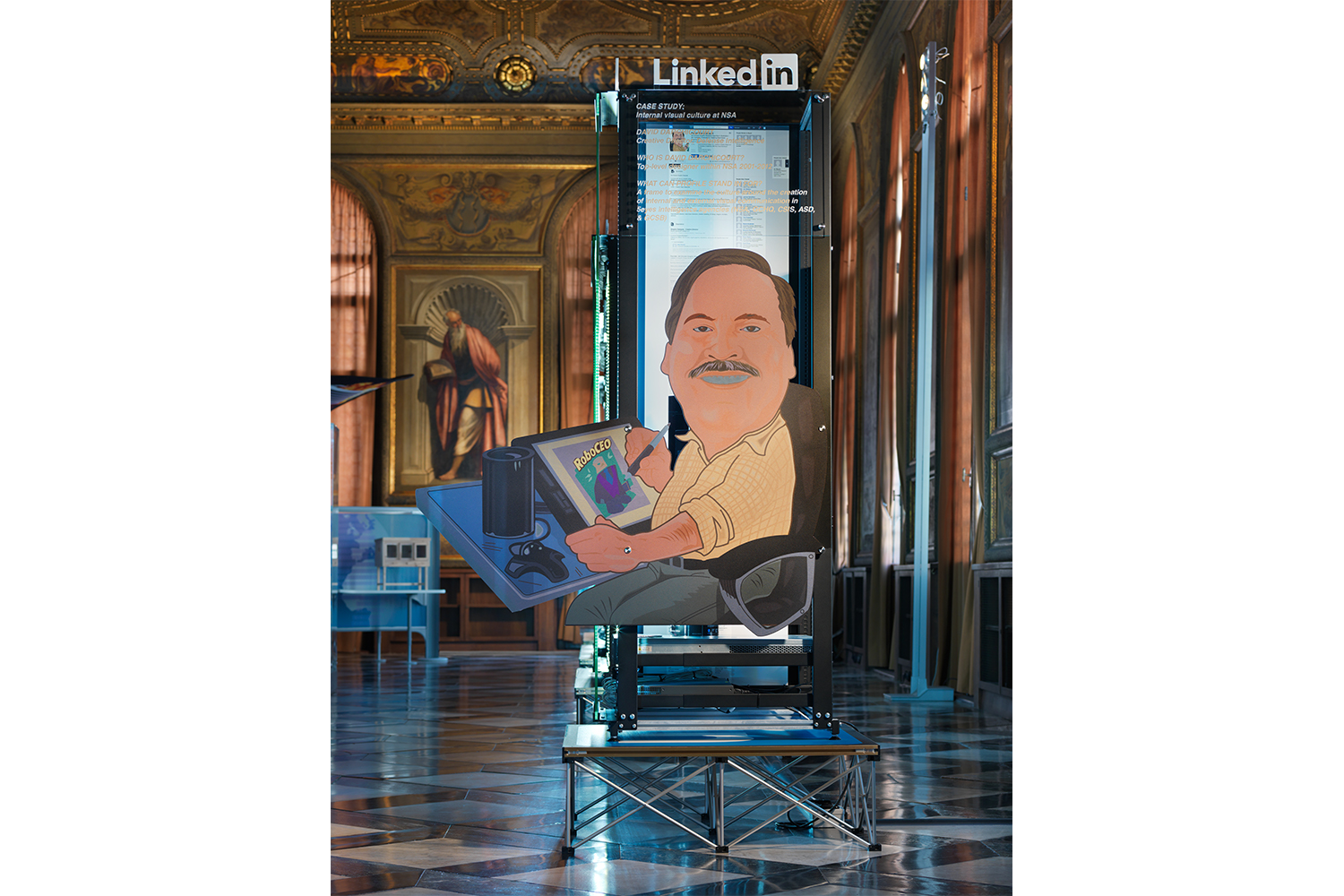

SD: There are always new “vulnerabilities” that can be “exploited” — protocols, politics, and discourses always change, and with change comes new opportunities for the literate. But it also depends on who one considers the hijacker to be and what constitutes a hijacking, which is I guess about power and legitimacy. Recently I made a couple of NFTs that hijack older tokens on the Ethereum blockchain and replace their images and some metadata — minting an NFT in the past, so to speak. This is a kind of artistic hijacking. But politicians and corporations also hijack — and “Products for Organising” at the Serpentine and “Secret Power” at the Venice Biennale were small exhibition gestures highlighting some of these strategies, with the latter using the New Zealand pavilion as a container to celebrate the work of an NSA artist, and in the process claim it as official New Zealand culture. That was also an opportunity to underline the way New Zealand’s culture is tethered to the politics of the US. “Disruption,” when used as a term to describe the emergence of businesses in web 2.0 — though now emptied out of meaning by repetition — is also kind of true. Facebook really was disruptive; it hijacked attention and leveraged sociality for profit in incredible new ways. The whole crypto project, and what that is doing to money and the legacy tools of governance available to nation states, the way it has opened the door to private, supranational currencies, allowing some people to essentially hijack finance, is absolutely astounding. There are many opportunities there.

ST: You often appropriate the aesthetics, mechanisms, and cosmology of the neoliberal economy and technosphere — business and speculative models, corporate expos, diagrams, and advertisements — as a way of making them legible, often via alternative contexts like video and board games, as well as galleries. What are the implications of the metaverse for your practice, which often elides the ludic with the artistic?

SD: The most tangible project I have done that uses illusionistic online environments is a layer of an exhibition I made at the K21 in Düsseldorf in 2020, which included a version of my exhibition “Mine” in Minecraft. I worked with Jan Berger, an artist who runs a space on Minecraft to produce a doppelganger of my exhibition as if it were installed beneath a very famous historical coal mine in the region: the Zollverein. That was quite an amazing experience, because my exhibition in the museum was made of sculptures depicting machines that automate mining. Jan produced blocky Minecraft versions of these, and some panels that stood in for videos or wall works. Right away, even before we “opened” the exhibition or publicized it, there were trolls and vandals present in the Minecraft environment we built, destroying things. They took down every image they could, and even when we built what we thought were secure vitrines around objects, they were also attacked and dismantled. It was amazing — so much activity to undo our gesture. We also had a “let’s play” YouTuber review the experience, and in that gesture he built his own automated drilling machine in Minecraft, something that was beyond our experiment in porting the exhibition into the game. That was really impressive because it was taking the exhibition and expanding it, based on the interests I had started with in the gallery and really working with the Minecraft medium in ways I couldn’t have imagined with people I’d had no interaction with previously.

ST: Your cycle of exhibitions titled “Mine,” shown most recently at Petzel Gallery in New York, addresses the mining of both minerals and data. How do you view the role of nonhuman labor in the minting of NFTs?

SD: There is so much nonhuman labor involved in all kinds of extraction. Machine labor is nonhuman, but also kind of human, in that some humans conceptualize and build machines to achieve things they want — acting in a space that is sensible to humans. A central symbol in many of the “Mine” shows also highlighted the early role of sentinel birds in sensing toxicity to humans. But the truly awesome nonhuman labor involved is hard to sense and hard to qualify for many humans — it is seen by mining companies and I guess by extension the end user, as a kind of externality. The millennia-long process that produces the energy and minerals mining extracts is all nonhuman, intertwining the activities of many elements and life forms over scales and time frames that are not accounted for by those who mine.

ST: In “The Founder’s Paradox” (2018) as well as the aforementioned exhibitions, you align the gaming mentalities of Risk or Minecraft with geopolitics. How do you view the current political geography of the blockchain?

SD: I find the work of Jaya Klara Brekke the most generative read of blockchain’s political geography that I have encountered. Her PhD explores the sites of emergence of blockchain politics in ways I can’t do justice to. There are still distinctions to be made across communities that claim blockchains and form and live the cultures around them. For sure, there are libertarian Hayekians and market fundamentalists alongside those who are technically minded and believe blockchains contain ways of ensuring equal access across political borders. There are socialists who like blockchains too — and a wide range of broadly speculative opportunists who are interested in building or profiting regardless of where the politics sits. Much of the activity is still in the US, with pockets across Europe and other affiliated regimes. China, which has contained a lot of activity, is now a harder place to work in cryptocurrencies, as they’ve been made explicitly illegal. That’s interesting because I’ve heard conservative speculation in the past that China was keen on Bitcoin because it (in theory) undermined the US dollar as the default global currency. But now it appears they see it as a tool of the US, as a form of US-led global liberalism. It will be interesting to see how these political geographies evolve. The El Salvador example is an interesting one also — resonating with lenient countries like Estonia and Portugal in Europe. It’s much easier to pay taxes on crypto earnings in some countries. Germany, where I live, is not one of those countries, even though a number of major Blockchain developers have been based in Berlin for some time — Gavin Wood, Parity, Polkadot, parts of the Cosmos ecosystem, OS coin, Gnosis, and many more projects. It’s unclear if that will be the case going forward.

ST: You’ve used the term “fan art” in relation to your 2016 exhibition “Blockchain Future States.” How do you view crypto’s prehistory before NFTs colonized the discourse? Has crypto art lost its innocence in the process? Do NFTs inhibit critical artistic strategies?

SD: Fandom was a mode I used, and still use in my work. Sometimes leveraging the fan position has opened up ways to learn and understand more about cultures. One thing I would say is that I’ve never viewed crypto as a space containing much innocence — there are too many scams per capita for innocence to really be a thing. One can be naive in crypto, but I’m not sure one can be innocent. The artists I got to know who were making art using blockchains prior to NFTs certainly tended to be highly literate, probably politically invested, probably interested in intellectual games and histories. Since the growth of NFTs and their intersection with the graphic arts, auction houses have cooperated with those with a lot of crypto wealth essentially to add a legitimizing string to the wealth claims of crypto. But, of course, like every other form of cultural opportunity, there are possibilities for all kinds of usages of NFTs — and there are artists able to use the format for critical artistic strategies. They’re maybe some of the same players who were using blockchain before NFTs, but they’re wonderful artists and artworks. I’m thinking of Sarah Friend, Terra0, Rhea Myers — the kind of people making NFT artworks that one can place easily in a conceptual art tradition.

ST: Throughout your work, you adopt an aesthetics of flatness through diagrams and infographics that compress complex phenomena into units of global algorithmic abstraction. Does the flattening of cultural tropes into NFT form resonate with you? Has it felt like a natural medium to work with? Or does it jar (perhaps usefully) with your wider practice?

SD: For me, the format of the NFT was an invitation to use it as a package for conceptual art ideas. The format is so restrictive anyway (with initial platforms like OpenSea, which many others rely on, having quite strict file size and type restrictions) that the possibilities were quite reduced anyway. A small JPG or MP4 was all that seemed possible at first. So I responded to this by using them as containers for ideas, rather than restricting the artwork to the visual component of what the file could carry. I’ve produced NFTs that pose as carbon offsets, linked to the act of minting portraits of miners, that are then taken out of the Ethereum network and used instead for climate modeling; I’ve also done an NFT collaboration with an economist that mints his most famous chart as a charity fundraiser where profits are donated to the Swiss state (in a gesture that “returns” some value to nation states that have been hijacked by crypto); I’ve “backdated” NFTs by hijacking old tokens, replacing their assets with older works of mine; and other things that use the NFT format in a way that is not primarily about the visual qualities of the file that’s listed or linked to on the blockchain.

ST: In the past, you’ve questioned the growing “financialization of experience” and the “cultural reach of market logic.” How do you feel about crypto art’s speculative trajectory having minted your first NFTs?

SD: Well that trajectory is continuing, and NFTs are definitely a part of it. If one has a document that everyone can read that says who owns what asset, then that’s maybe the first step toward being able to “enclose” all parts of what up until now has been a default common on the internet. It’s hard to control and police the use of material on the internet, but perhaps NFTs are a first glimpse at alternative ownership models. Decentralized Finance (DeFi), or doing with crypto what banks do with money — putting value into increasingly abstracted packages and then trading, lending, and selling them — is a direction where one sees possible futures along these lines. We could see more and more types of assets abstracted into packages derived from our activity: assets that reflect social value or other kinds of properties that are more or less tangible. Those assets, penetrating further into our systems of value as humans, could be traded and worked with in complex markets, like in DeFi. One gets a sense of this in a very tangible way with NFTs. The first NFT I minted this year was bought by a project called K21, which is a collection of many artists’ works that are then packaged as a group and tethered to a token they release — which is somehow reflective of the value in the artworks — that people can own and trade. One can imagine this kind of gesture being repeated with other assets that are not artworks.

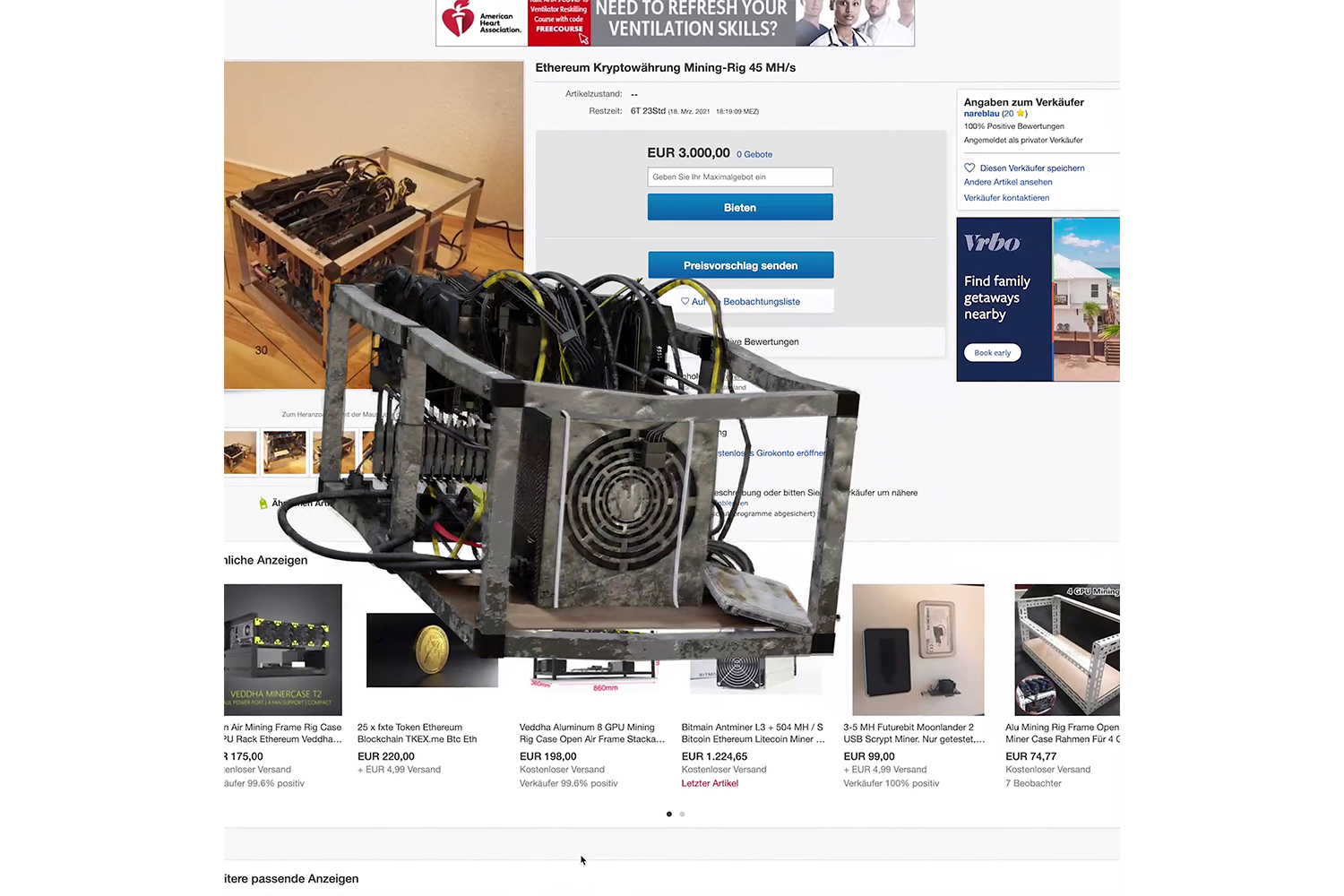

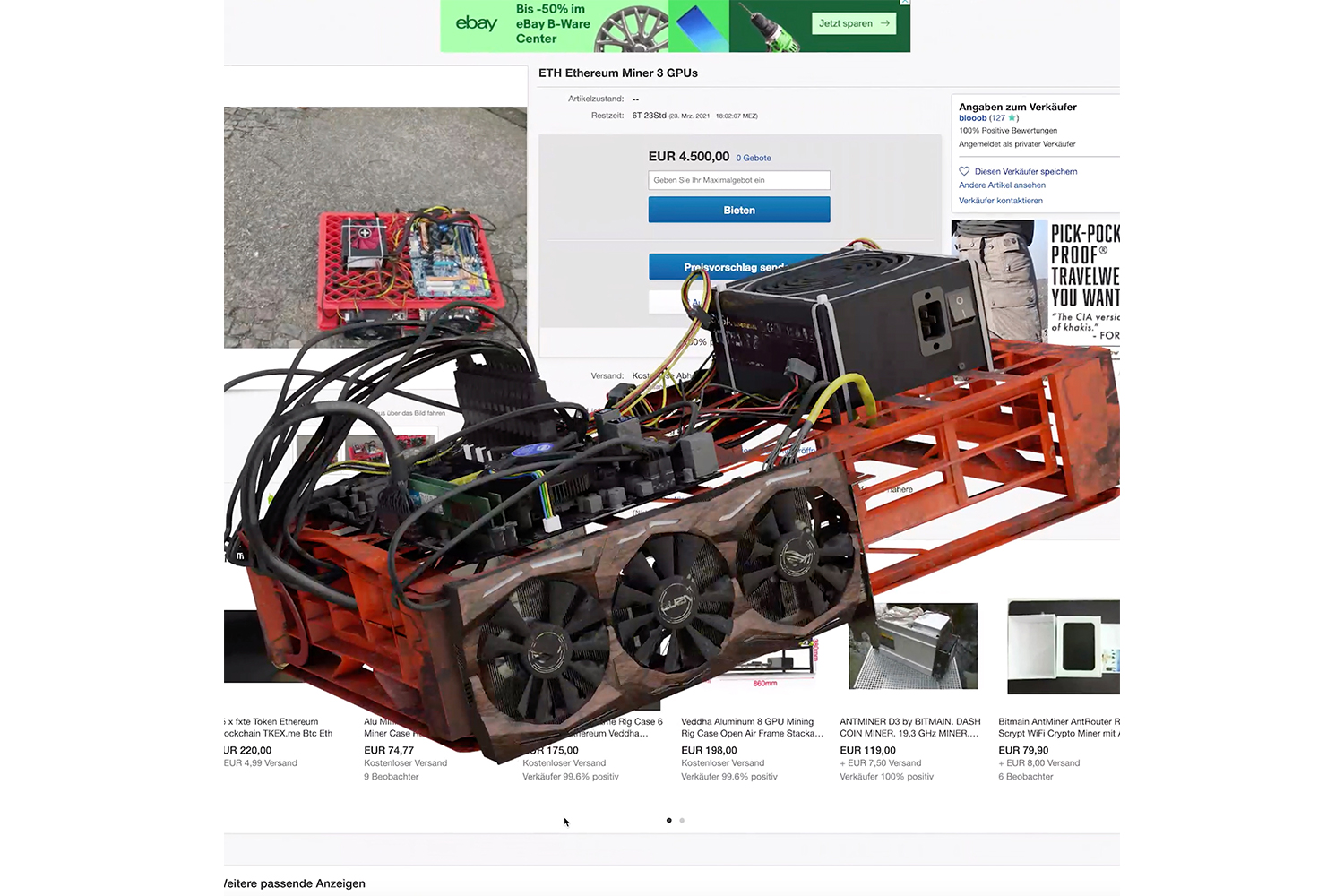

ST: Your “NFT Mine Offsets” (2021) are 3-D models of cryptocurrency mining rigs. As a part of the package you channeled a physical mining rig’s computational energy to support climateprediction.net — an environmental research project. While these NFTs operate to critique the market’s carbon footprint, can one realistically maintain a subversive politics while fuelling speculation?

SD: That’s a great question. I think there are many artists I admire that have worked to produce artwork that is a participant in systems that their work clearly asks meaningful questions about. I think one can do this in ways that keep a poignant urgency to the work, and I think one can also do this in ways that make the gestures seem compromising and undermine some of the effectiveness of the work. I’m not sure if those gestures or those artists necessarily “maintain a subversive politics.” I’m also not sure that this is always the purpose of the work, or the measure of its value for me.

ST: Can you talk about how your project “Proof of Work” (2018) as well as your forthcoming “Proof of Stake” (2021) apply blockchain principles to curatorial practice, specifically through “distributed curation”?

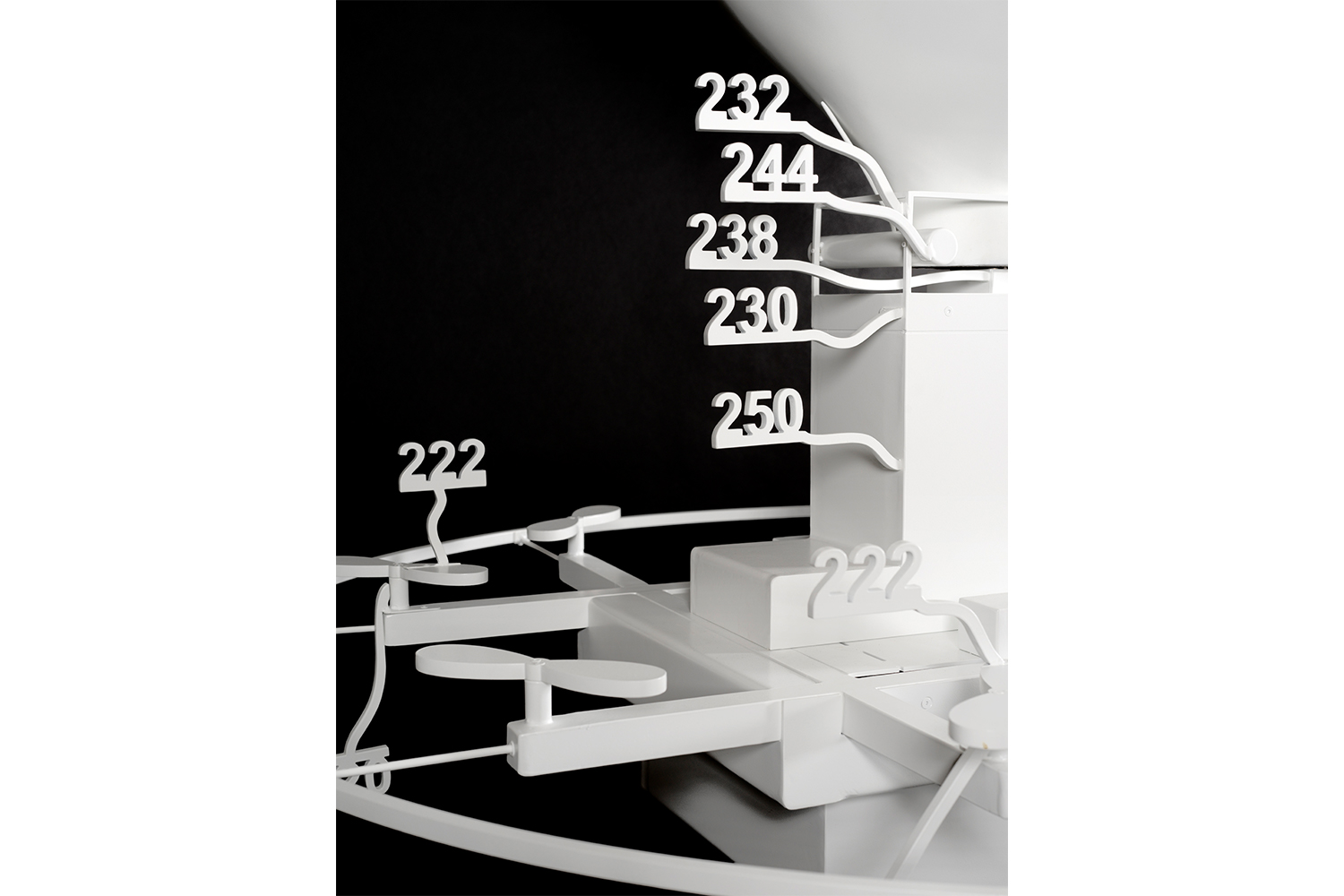

SD: Yeah, the “Proof of Work” exhibition project at the Schinkel Pavillon definitely tried to distribute authorship and curatorial ownership of at least parts of the process. I asked several artists and curators to choose artists and works to be in the exhibition, and then I facilitated the work and produced a layout and exhibition design that blurred the boundaries between artworks and authors. This process was documented in a diagram that viewers encountered at the start of the exhibition, and also served as the opening to the guide booklet. It sought to be very transparent with how decisions were made, and to allocate power across a slightly broader set of actors (which is very often how curating happens anyway — this is maybe just making it rather more explicit). One of the other things “Proof of Work” did was to try and bring artworks that were explicitly made with blockchains and about blockchains into dialogue with works that were absolutely not made with that context in mind, to try and broaden the conversation a little. “Proof of Stake” tries to do this again, with a subsection curated out to a set of scholars who select objects for exhibition, and there have been a couple of interrelated seminars held between the University of Lüneburg, the art school HFBK, and the Kunstverein in Hamburg, which have preceded the show opening on September 3. Again, I’ve tried to mix discourses a bit, and the central theme of “Proof of Stake” is to open up the question of ownership — both of “things” but also of concepts or even whole categories like the “technological.” Who gets to claim a “stake” in something? How is that recorded and measured? Who also gets to claim the technological, and what does it mean when certain groups do? There are a lot of ways in which “Proof of Stake” is mixing up these questions. There are sculptures and paintings from indigenous positions that question models for cultural and technological ownership, both historical and contemporary, next to NFT art that has been involved in the recent speculative boom, next to blockchain mining works that ask structural questions about the way NFTs are produced and circulate, next to disused vitrines from a display of the Museum of Ethnology Hamburg (MARKK).

ST: Your NFT Backdated NFT/Ethereum Stamp (2021), recently sold at Sotheby’s, reimagines an earlier work, Blockchain company postage stamp designs: Digital Asset, Ethereum [with Linda Kantchev] (2016). This seems to respond to a tendency of artists to reheat prior works as NFTs in order to build hype and make a quick sale. Is it possible to identify artistic strategies that could only work as an NFT?

SD: Reheat is a nice term. Yeah that’s partially what interested me in making that work. There seemed to be one tendency in NFT production, particularly in 2021, where images of older artworks or even things that were not artworks, like memes, were being minted as new NFTs. To me this kind of work raised a number of questions about what an NFT was. It also made me think about time — both artworks’ relationship to time and the claims of the immutability of timestamping on blockchains. There’s a crucial relationship between when artworks are made — when and how they become visible, seen, discussed, and processed socially — and their value and meaning. What happens when you have a way of remaking a work that is outside of the time and context of when it was produced and digested? I wanted to open that up a bit, but I also wanted to challenge the immutability claims of blockchains as well — and it turned out that there was a kind of “party trick” I could use that was already in the NFT structure itself — a vulnerability that I could exploit. NFTs on the Ethereum blockchain, managed by marketplaces like OpenSea, are not technically immutable stores for images, they only “point” to the images they claim to relate to, and the places they “point” to are not hosted on a blockchain, they’re on the open web. This means the digital assets that a blockchain entry points to can be changeable. For instance, you can stick a different image in the URL that hosts the original image. So, I did exactly that. With the help of a friend who had some NFTs minted in 2018 and 2019, I bought those older tokens and asked him to swap the asset attached to their minting date with a new image of my older work. I claimed that this was a “backdated” NFT and, as it were, that I was minting the artwork in the past. I took an edition of a stamp I made in 2016 and rubber- stamped the 2018 NFT’s details on top of it — kind of an analogue “time stamp” — and sold the objects and the digital image as a record of that act as an artwork. That’s a gesture that could only work as an NFT — creating artworks in the past. There are many things that can only really operate as NFTs — and in a way, the tethering of artworks directly to currency is bound to produce a kind of artwork that one wouldn’t expect. I’m sure there are many strategies that are in different ways native to the constraints of the format. Even reissuing older artworks in a different form is hard to imagine without NFTs.

ST: What are the limits of the blockchain as a technological tool for reconfiguring our contemporary aesthetic, financial, and ideological systems?

SD: I don’t know. I don’t think we’ve seen the effects of blockchains yet to their full potential, and maybe it’s not a static thing that one can measure in isolation, but rather blockchain is a tool of the moment, that captures a lot of hopes and fears and deploys them in a speculative container that people seem to really respond to, for better or for worse.