Anyone who has experienced a high school– or undergrad–level art program may look back at their painting or sculpture course and remember, under the guise of naïveté, that the signature, when applied, communicated a sense of ownership, accomplishment and authenticity. Today, the artist’s signature in the context of the contemporary art world, however much it does or does not involve this naïve reading, concerns other applications worthy of note: its usage as a valuating device by collectors and dealers in the art market and its history of deconstruction by conceptual artists. Further, the artist’s signature’s long history of deconstruction can be divided into multiple parts that become more complicated with the progression of time: through Marcel Duchamp, the politics and denial of craftsmanship and authorship; through mid 20th-century artists Robert Ryman and Marcel Broodthaers, the formation of a signature ‘style’ and the complexities and ambiguities of its valuation; through contemporary artist Josh Smith, the dissolution of the artist’s subjectivity; and toward young artists Tyler Coburn and Oliver Laric, who further examine forgery and authenticity. To be sure, the deconstruction of the artist’s signature is somewhat historical and, that is to say, old fodder. However, ascribing a historical lineage to work being made today amid the advent of a technological and intellectual metamorphosis should help deconstruct the constellation of art production as we know it. What is the contemporary signature? Is this work relevant to artistic practice today? How have issues represented by the signature developed in tandem with the advent of recent paradigm shifts brought forth by technological innovations?

To be sure, it is redundant to begin such a lineage with the work of Duchamp. However, his notorious Fountain, falsely signed R. Mutt, seems its most logical undergirding. Famously, Fountain features a porcelain urinal inverted ninety degrees on a pedestal signed by the fictitious Richard Mutt in black enamel. Fountain provided one of the earliest disavowals of the demand that an artist must physically craft their objects, and by extension it challenged the principle that an artwork’s value is intrinsically tied to the amount of labor imbued within it. Duchamp’s treatment of the signature further complicates this reading. Oddly, at the time of Fountain’s presentation at the Society of Independent Artists’ 1917 opening, Duchamp acted as that committee’s chairperson. This is to say, Fountain probably would have been treated differently had it not been entered into the exhibition by a theretofore unheard-of artist. Here the signature acts first as a form of nomination: the urinal is art because an artist has signed it and henceforth designated it as art; and secondly as a form of evasion or forgery. Since Duchamp entered the sculpture under a false name, the true identity of Fountain’s creator wasn’t revealed until the story “The Richard Mutt Case” was published in The Blind Man, a periodical created by Duchamp and fellow artists Beatrice Wood and Henri-Pierre Roché to create an editorial-free sounding board for artists.

If Marcel Duchamp employed the artist’s signature to challenge notions of authorship and responsibility, minimalist painter Robert Ryman employed the device to call ‘signature style’ into question. In 1953, Ryman took a job as a security guard at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. There the artist was surrounded by the museum’s collection of abstract painting masters such as Henri Matisse and Arshile Gorky, as well as Abstract Expressionists Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, among others. Although it will remain a leitmotif throughout the artist’s career, Ryman’s early work evidences the digestion of these masters’ signature style, often redistributing elements of his predecessor’s compositions into his own.¹ Further, Ryman began layering his first initial, last name and date (i.e. RRYMAN58) in decomposed, large block letters within these compositions. (Curiously, Arthur C. Danto notes in The Madonna of the Future that the double “R” of “RRYMAN” bears a serendipitous quality to Duchamp’s nom de femme, “Rrose Selavy”).² To Gertrud Mellon (1958) was among Ryman’s first exhibited paintings, shown at a MoMA staff show that same year. An illustrative nascent piece, To Gertrud Mellon bears resemblance to a heavier Rothko while Ryman’s initials begin to approximate the artist’s geometric style.

Marcel Broodthaers, who originally studied chemistry in his native Brussels, turned from writing poetry to creating conceptual art, to finally making films until he died in 1976 on his 52nd birthday. The heart of the artist’s practice comes to terms with his deep dissatisfaction of the complex, paradoxical nature of the so-called culture industry. How can an artist create sincere objects of cultural critique in an industry whose capital is controlled by the collectors it seeks to challenge? Further, what is sincerity in artistic praxis? As Anne Rorimer notes in her 1987 essay “The Exhibition at the MTL Gallery in Brussels,” one of Broodthaers’ more powerful and direct statements about the “pitfalls of artistic production” exists in the poem “Copyright,” shown amongst many typewritten and hand-drawn manuscripts at the aforementioned 1970 Brussels exhibition. “The eel, already a commodity / before it escapes the slippery hands of the fisherman. / Beware of fakes — of the snake and the blindworm.”³ Here Broodthaers posits that the commodity status of a work of art is at times predetermined before its creation. He sarcastically warns us of “counterfeits” — the snake and the blindworm. Though they appear similar in form to the eel, they lack the eel’s qualitative essence. (Similarly, a piece of Ikea furniture may appear akin to a Donald Judd sculpture, but lacks its historical specificity and other qualifying factors.) Rorimer goes on to highlight an essay written by Broodthaers two years after the MTL presentation for his Dusseldorf exhibition “Der Adler vom Oligozän bis heute,”⁴ which she argues make distinct on one side “the principle of authorship, and on the other … the authority of the exhibition space.”⁵ Broodthaers critiques Duchamp’s dissolution into complacency within the institutional system of art:

Whether a urinal signed “R. Mutt” (1917) or an objet trouvé, any object can be elevated to the status of art. The artist defines the object in such a way that its future can lie only in the museum. Since Duchamp, the artist is author of a definition.

Two facts will be brought into focus here: that in the beginning Duchamp’s initiative was aimed at destabilizing the power of juries and schools, and that today — having become a mere shadow of itself — it dominates an entire area of contemporary art, supported by collectors and dealers.⁶

Broodthaers expresses dissatisfaction with the nominalization of a found object into ‘art’ insofar it may only exist within sanctified institutionalism. Although, throughout his career, Broodthaers did consider Duchamp a historical character worthy of doting upon (playfully and critically), and likely saw Fountain as an important step in art history that freed the artist from the burdens of necessary craftsmanship. But, in Broodthaers’ mind, how radical is it to ascribe authorship to an object — an objet trouvé or otherwise — solely for it to function identically as a commodity form in the art market system? Not very. MB MB MB (1968), finds the artist’s initials “M.B.” scrawled on a black picture plane, positing that, to collectors and dealers, the most primary aspect of a work of art exists in its nominalization. Although Broodthaers’ work illustrates these polemics with fervor, perhaps unavoidably it also becomes an object of the art market and institutional system.

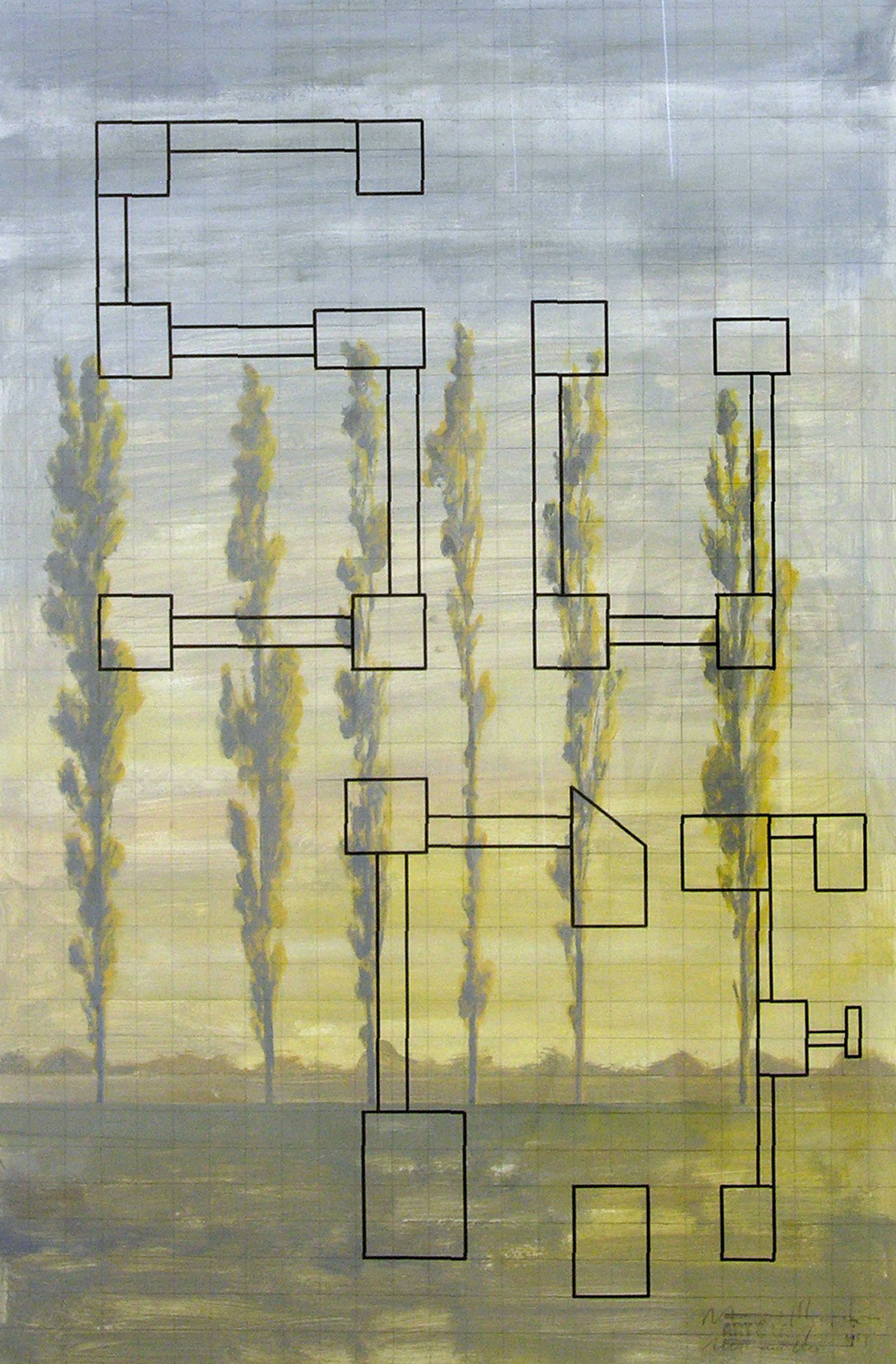

If Broodthaers placed primary importance on his initials in his work’s composition, American artist Josh Smith seeks to confront issues of subjectivity in painting by treating his name — an increasingly common American one — as a debased, meaningless form through its dissolution and ubiquitous usage. Similar to Ryman, Smith is known for his longstanding engagement with extending, warping and decomposing his name as a framework for his paintings. Smith is known for prolifically churning out energetic if not slapdash work. For his November 2009 exhibition “On the Water” at Deitch Studios in Long Island City, New York, the artist completed 47 canvas-less paintings applied directly to the wall over the course of three and a half days. Whereas primary importance is generally placed on the ego of the traditionally machismo painter — take for example Jackson Pollock or Yves Klein — Smith subverts this by rendering his signature as a meaningless construct.

Heretofore, all included in this lineage represent artists working through traditional, plastic forms of artistic practice, often in attempts to challenge their historicity and very nature. Tyler Coburn and Oliver Laric, two young contemporary artists, complicate the historical readings of this lineage in theory and form. For “Today I Made Nothing,” a labor-themed exhibition at Elizabeth Dee curated by Tim Salterelli in 2010, Coburn created Thumbprints & Other Takeaways (1960-2010), a set of three pedestals topped with reflective copper etching plates, creating a surface upon which viewers would leave their thumbprints. Upon these etching plates are three sets of Felix Gonzalez-Torres-style takeaways: a selection of smooth, round “sucking stones” (à la Samuel Beckett’s infamous Molloy, 1955); a sliced, oozing round of Camembert cheese; and a stack of white drawing paper with various signatures of Salvador Dalí etched in graphite. The three pedestals represent three unique methods of artistic production. The sucking stones — bringing to mind Rosalind Krauss’ 1978 essay “LeWitt in Progress” — represent working through a fabricated system of logic.⁷ Coburn’s liquidated cheese refers to the a-ha! moment in which Dalí sat down to a lunch of Camembert and first envisioned his signature melting clocks — or more specifically, the synthesis of work and leisure. Lastly, and perhaps most pertinent here, is the artist’s stack of heavyweight drawing papers etched with various signatures of Salvador Dalí in the bottom right corner. At first glance, the signatures appear to be authentically written in by Dalí himself — Coburn even goes so far as to credit him as a collaborator, which, needless to say, is illegal. The artist actually etches the graphite signatures onto the paper (the etching copper is a good clue to determining authenticity), toying with notions of forgery. Notably, toward the ’60s Dalí ceased to create art but frequently signed sheets of paper onto which reproductions of his previous work were printed out of financial motivations. Perhaps Dalí’s is exactly the modus operandi that Broodthaers abhorred. And, perhaps Coburn’s forgeries jam the system in a way that would impress both Duchamp and Broodthaers. Though the work exists complacently in a market economy and art historical vernacular, these are implicitly challenged by their obvious illegality.

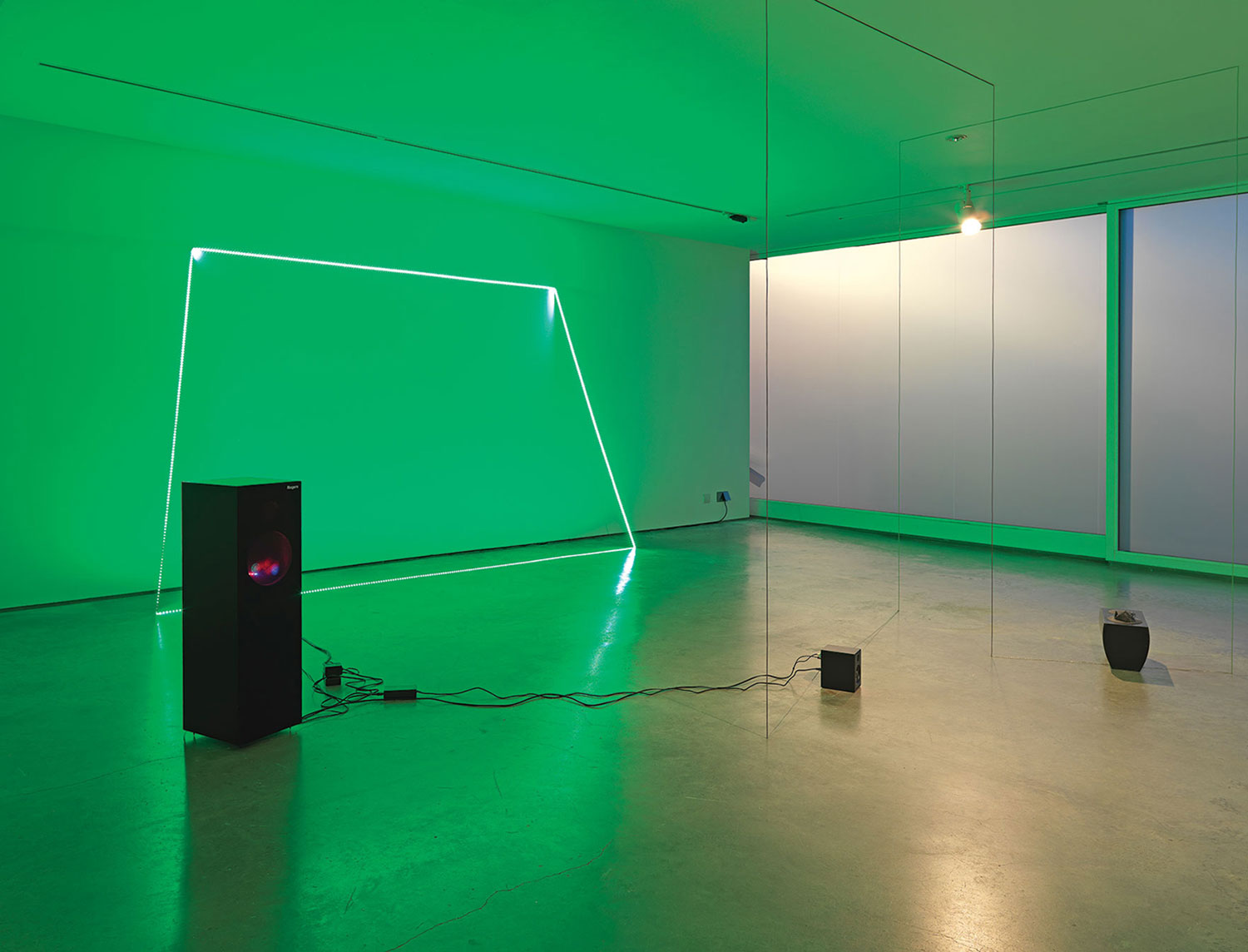

Whereas Tyler Coburn updates the lineage of the artist’s signature in theory, German artist Oliver Laric does so in form. Laric, primarily an Internet-based artist who has recently expanded his practice to include the plastic arts, fits in here only by extension. His 2009 work Versions, originally a video hosted on the artist’s website, now exists in permutations of sculptures, takeaways and commissioned ‘versions’ of the initial video by other artists. The video, narrated by a synthetic female voice, pairs an academic text on the Internet’s role in deflating the hierarchy of images in cultural production. Beginning with an image of a missile launch doctored by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, Versions illustrates this principle by offering the onslaught of outlandishly photoshopped images posted online in response to the unveiling of the doctored image. In the realm of the Internet, Laric asserts, all images are created equally, and “authenticity is decided upon by the viewer.”

Versions perhaps points to the crux of the work presented here. The co-mingling authenticities and subjugation of authorial power further explicates the authorial displacement of Duchamp, Ryman’s conflation of styles, the formal disavowal of Broodthaers, and Smith’s dissolution of historically privileged subjectivity. Further, the authority of these works, on one level, often resides in the act of designation or nominalization — Laric’s authenticity is a construct dictated by the viewer, while to Duchamp, the status of art remains in the nominalization of the artist, whereas in the case of Broodthaers, an external “qualitative essence” precludes form to create genuineness, and so on. If the artist’s signature represents a long-standing battleground unto which institutional resistance may be wrought, the future of such discourse seems cast as a nomadic, multidimensional platform for subversion.