Ser Serpas assembles situations through poetry and sculpture, painting and performance. In the 1995 Los Angeles-born artist’s ever-mutating practice, everything is about remaining in transit, alert, and afloat. Having studied at Columbia University in New York and encountered her elective scene there — artists, activists, and internet weirdos alike — the artist later moved to Zurich and Geneva, before recently relocating to Tbilisi in Georgia. Whether writing in trains or drawing in public spaces, collecting gifted or found debris of late-capitalist society, or learning how to paint the fragmented bodies of maybe-lovers, Serpas reclaims agency from inside the late- capitalist matrix through a seemingly improvised execution carried out during trance-like, private moments. What we, the viewer, experience is transient moments of fleeting grace that command our rarefied attentional currency to attune itself to the artists’ quasi-musical scores in space. If only for the duration of a show, the curse to continuously self-update and self-represent is lifted. A shared intimacy slowly resurfaces for those willing to follow the wake of the artist’s both eruptive and fragmentary path. Recently, the artist has had solo shows at Luma Westbau in Zurich (2018), “Models” and “Two Take Red Series” at Karma International, Zurich (both 2020), at LC Queisser in Tbilisi, and at Galerie Balice Hertling in Paris (both 2021). She was included in the 2020 Made in LA Biennial at the Hammer Museum as well as the opening show of Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection in Paris (2021). Her first poetry book, Carman: Based on the Opera, was published in 2019, and the second one, Guesthouse, a few months ago.

Ingrid Luquet-Gad: I got to know your work through your poem collection Carman: Based on the Opera (2019) that a friend gave me, so I first wanted to speak with you about your writing and what role it plays inside your practice.

Ser Serpas: Do you remember the performance art duo called DarkMatter? It was formed by Janani Balasubramanian and Alok Vaid-Menon, and all my friends were into them as they were those social-justice geeks doing poetry. I was an organizer in high school myself and I already knew writing, stand-up, and millennial poetry. So, we went to see a reading at New York University, in 2013, and on the train back to campus that night I wrote two drunk poems. I was doing Urban Studies at Columbia University, and by the end of freshman year I had a lot of writing in my iPhone notes that I would sometimes look back at.

ILG: Were you already thinking to make something out of it?

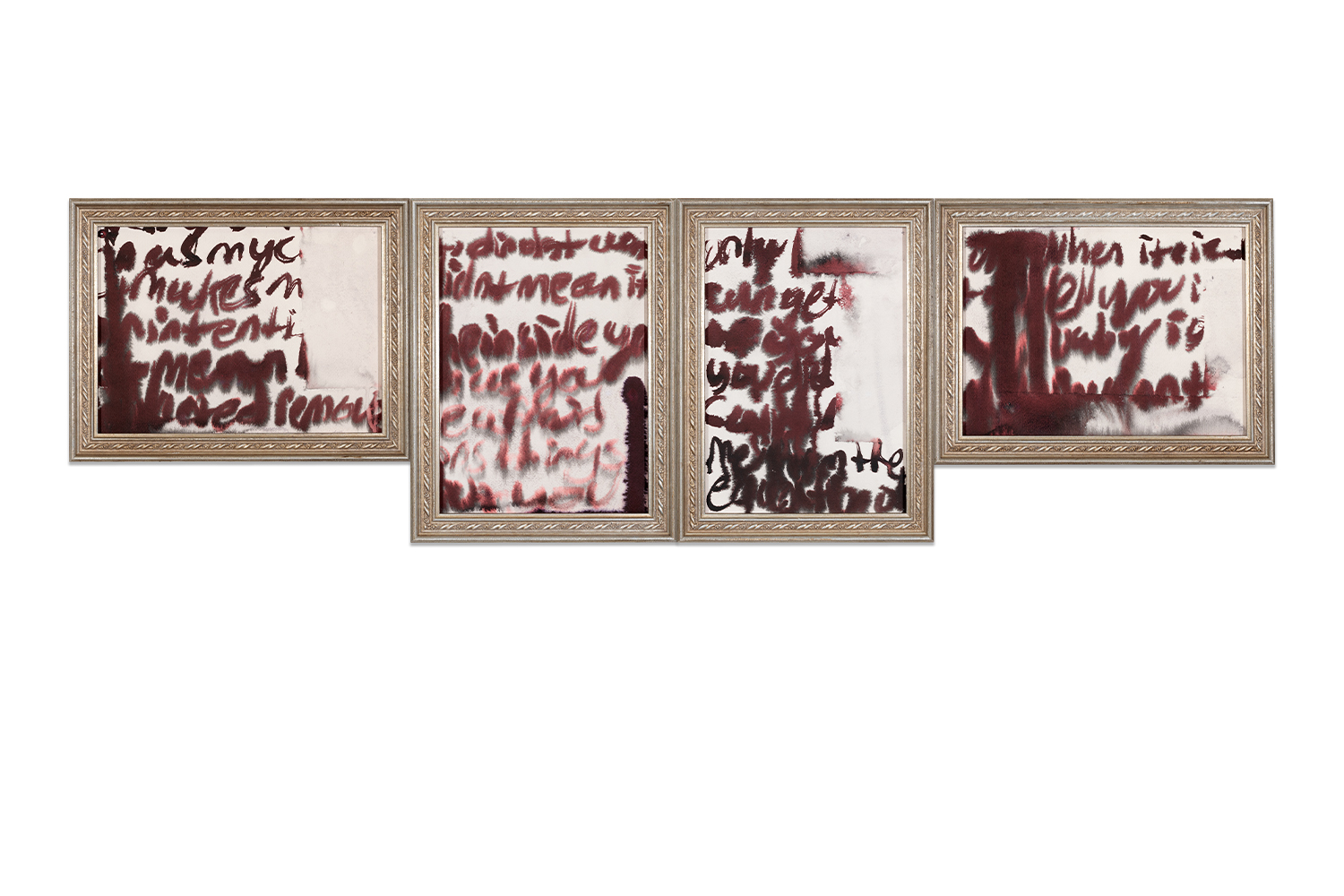

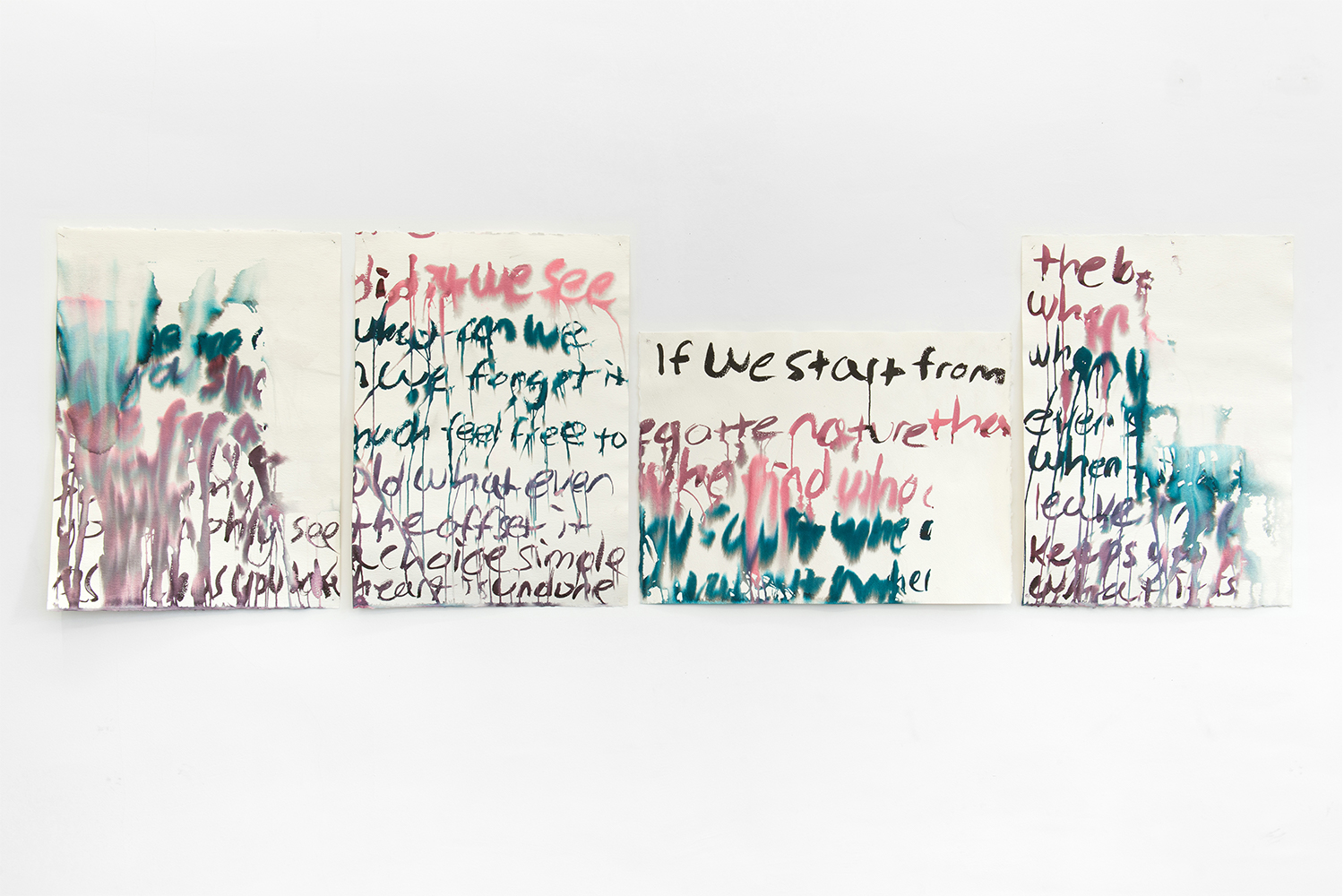

SS: No . It wasn’t until two years later that artist and poet Manuel Arturo Abreu, who had invited me to poetry readings online, thought that I should compile some of my writings. Every year, I was writing around ten poems; I would just take a train or a cab to go somewhere and then write. I always write in transportation, and usually very caffeinated. I see the poems as time-sculptures – like most of my practice – and I collect them in four-year cycles. In Tbilisi for the show “Guesthouse” (2021) I was able to publish a new book, Guesthouse, which was conceptually the exhibition that I filled with works about writings, language, translations, inks melting and dripping.

ILG: Your paintings and sculptures retain a similar quality of remaining in transit and not getting attached to anything for too long. How did you make the move to make works in space?

SS: I was also drawing, usually in between the writings. Both started as something I would do during classes, and when I’d get distracted I would mostly draw. It was about being in public and being watched, in the sense that some people can only write in cafés. At that point I was just filling notebooks that I usually shoplifted, while also having jobs in fashion PR or styling and making friends that were either in performance art or internet weirdoes.

When I decided to take a sculpture class after urban studies, my professor, Sanford Biggers, made us take metal and wood workshops. For one assignment, I didn’t make it to the wood shop on time, but I had all the clothing I had gathered from assisting stylists. I made four sculptures out of that, which was the first time that I worked with fabric. They were garments with hangers, composed from clothes, my odd stuff — dresses, old bras, cleaning supplies.

ILG: We are meeting in Paris as you are installing your show at Galerie Balice Hertling, a sculpture show with materials found around the city. How did the collecting process evolve?

SS: My friend Donna Huanca invited me to her studio because I was in a performance with Women’s History Museum [Mattie Barringer/Amanda McGowan] in New York and she was painting the shoes on us. Initially, she was going to ask me to perform in one of her performances, but then she saw on my Instagram that I was making the fabric sculptures.

That’s when I realized that I could also work material that my friends gifted me. I guess it had always been about space: collecting material to fill other spaces and still have an efficient life. Plus, my mum always threw out my shit, because we shared the same room and she hated clutter, as it reminded her that it was all we could afford. The show that I made here at Balice Hertling, “Ser Serpas” (2021), is probably the one I worked the longest on all in all. It is mostly the collecting part that takes time; when I’m in there, in the room, it takes a couple of hours to put together.

ILG: Is it important to you that when looking at your works, the viewer knows that it’s yours or your friends’?

SS: If I were to really mark them with who is in the works, it would feel like too much exposure.

ILG: What was the initial reaction to your sculptures? Most art institutions would probably want to insert them into a certain tradition or lineage — from Duchampian readymade to Steven Parrino-ish punk minimalism.

SS: In a sense, anybody could do them, but even if it just feels chaotic, I have a process for everything I do. The same is true for the paintings, as I am not really a painter. At school, I was good at mixed media, collage, performance, but in painting classes I couldn’t even do the color chart properly.

But then I came back to Zürich after the show I did at Luma Westbau, “You were created to be so young (self-harm and exercise)” in 2018, and I wanted to finally have a studio. In the small space I could afford, I could make paintings. I also wanted to learn and teach myself, as my painter friends seemed to have a great time doing that.

ILG: You always have your painter friends and your other artist friends…

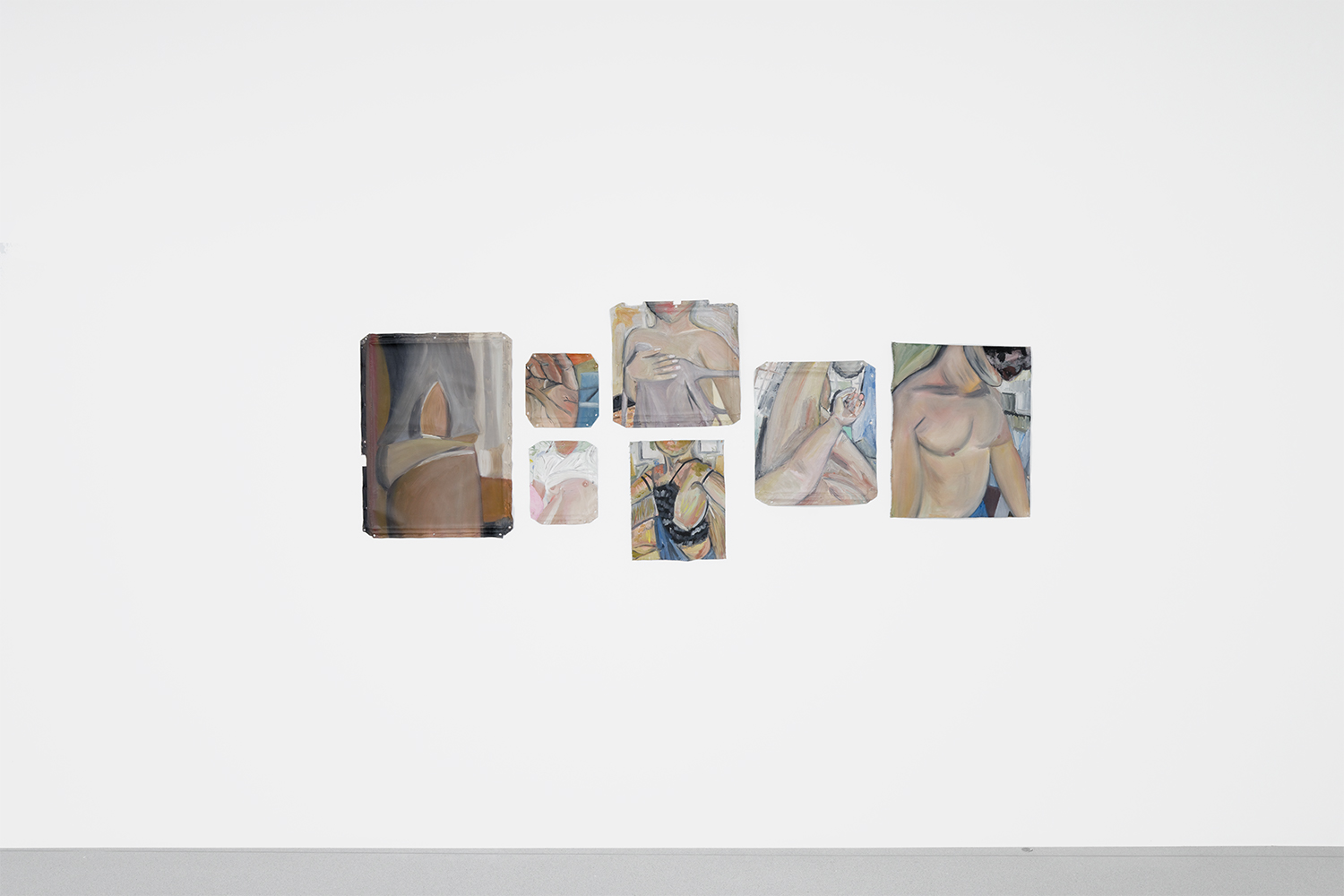

SS: Yeah, the way they talked about it was interesting to me. The first paintings I made were similar to my drawings, but I was not satisfied with them – I found them too flat, they looked kind of crazy. I was living and sharing a studio with Hannah Black at the time, and she suggested that I could maybe paint from some photos I had taken. I had all kinds of photos I could paint: landscapes, weird objects on the street, but I also had pictures from people I had been on a date with that didn’t work out and other people. I thought that I needed to learn to paint bodies, so I started to experiment.

ILG: You work closely with a tight network of artists, and other artists look at your work a lot as well. Did the reception of the works change when you started to get invited to bigger shows and working with institutional curators?

SS: At first, of course, because of who I was then. It became a power play. For me, it felt very personal: I was a broke college student and I was transitioning in front of a million people that I didn’t know.

When I did the show in Zurich, it was about how artifacts are handled: the show is set in the future with Swiss design and furniture, composed together in slapdash ways, because this is how actual objects are usually treated in museums. It started as a “fuck Europeans” show, and then I met nice people and eventually ended up moving there.

This was the moment when I started questioning the pill that I took that made me see red at the slightest infraction or when someone said the wrong thing. Initially, I was a brat, but I cooled off when I left the US to move to Switzerland, and then to Georgia, where I intend to be based for some time. I needed to gain some confidence in my life.

ILG: How do you feel about the mediatic pressure to appear as a persona?

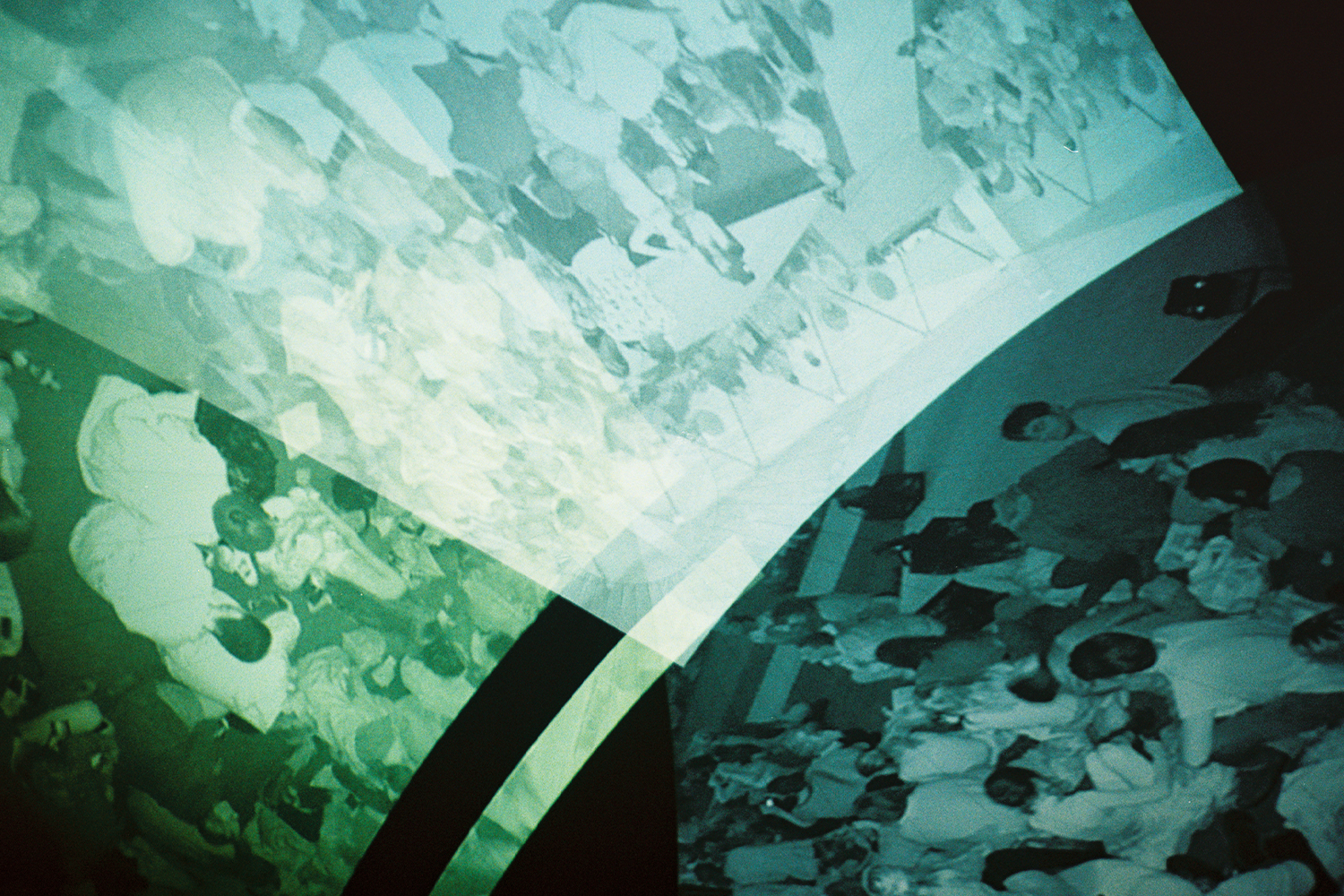

SS: At the end of college, the art teachers, who were professional artists in New York, liked what I was doing – the fabric works, the works on paper – but they wanted to see me doing it. They suggested that I record a video of myself in my studio, and I got so offended as I thought that they just wanted to see my body. I made a whole reactionary performance at MoMA PS1, Crumbling World Runway (2017), part of Sunday Sessions organized by India Salvor Menuez, where I made the audience sit on a tarp that I had left rotting out in my backyard in Brooklyn, and look at the ceiling where there was security camera footage. I was doing a DJ session on my screen and a poetry reading, really angry, and people were making sculptures in the background. Back then, I felt that I always had to protect myself from weird curators and weird people on the street.

ILG: Would you be able to have a studio with assistants working with you?

SS: I don’t know if that is ever going to be possible for me, if I didn’t have my hands on it. I know how to push things till they are about to collapse or fall apart, and that is the only way that it is interesting to me. If you go about it the right way, you can lock the energy in, if only for the duration of a show. Maybe it can never be put back together in the same way, which means it’s just going to sit in a box with me somewhere.

If I’m the only person that can activate it, this seems cool to me! In a sense, the work is the aftermath of a private performance or choreography that I did — and I’ve never broken a nail while doing it!

ILG: Looking back, do you feel that people are starting to want specific works from you or are you able to keep exploring new formats?

SS: Galleries want paintings and museums want sculptures, that’s for sure! But I want to keep on learning. Recently, I wrote a screenplay for a horror movie and it felt really nice to write in another format. Nobody has read it yet but I’m really happy about it.