Ed Ruscha’s objective inventory of life in Southern California is wholly determined by the road, the highway and freeway, as the first social incursions into a desert landscape that would seem to resist any such thing. Accordingly, everything that follows is automatically categorized under the rubric of the roadside attraction: the gas stations and liquor stores; the bungalows, duplexes and low-rise apartment houses; the parking lots and swimming pools; the street signs and billboards. The notable absence of any sign of humanity as such is, by now, recognized as a stylistic given of the topographic ‘genre,’ one reinforced within the works of Berndt and Hilla Becher as well as their famous students, but in Ruscha it is just as much a response to the on-the-ground conditions of life in Southern California where the bulk of the public either stays indoors or, like the artist, in their cars.

Ruscha picks up on a readymade style, conscious that it is conflicted from the first moment, and only becomes more so with time. Its Weimar precedents were devoted as much to a bleary-eyed resuscitation of disappearing values as to the steely-eyed affirmation of an endlessly perfectible future. Sentimentality and ruthlessness — these comprise the twin poles of every typographic picture, endowing Ruscha’s vaunted ‘flat-footedness’ with its political angles and emotional contours. Likewise, Judy Fiskin’s extended meditation on that much-maligned emblem of a West Coast architectural vernacular, the ‘dingbat’ house: The very flatness of the object lines up with the flatness of its depiction to suggest a new sort of depth, one that becomes historically charged precisely by virtue of its seeming indifference to history. As a pointed over-determination of Neue Sachlichkeit [New Objectivity] tendencies, at once secretive and exhibitionistic, the dingbats present the façade as a face that has melted into its mask, or vice versa. As opposed to the Bechers’ insistence on a consistent middle-gray skyline to set off the lights and darks of their chosen objects in the manner of ‘proper’ photographers, Fiskin opts for extreme over-exposure. The results are very much ‘like Ruscha,’ carrying over all the same intimations of cavalier Conceptual de-skilling as well as its cataclysmic effects, only more so. These homes are reduced to spare configurations of black outlines against a consistently clear white ground, giving them the appearance of being illuminated as much from within as without, and yet they stare back at us blankly — “lights on, nobody home.”

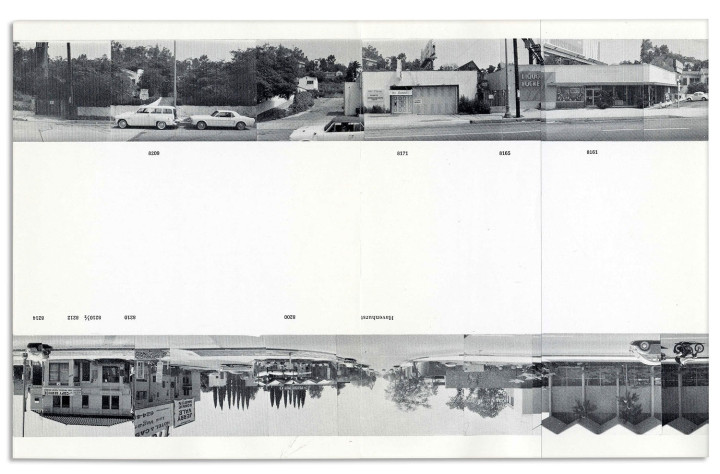

In a classic LA twist on the suburban idyll, Fiskin’s dingbats are emptied, if not cancelled-out, by the very light that renders them visible, every individual exposure detonating one more ‘information bomb,’ house after house, block after block. Here, claims John Divola, “everything really appears to be on the surface. The built landscape is like a crust that you have no expectation of lasting, one that can be simply raked off the surface of the earth.”1 In his recently reprinted “LAX NAZ, House Removals” series from 1976, Divola points to the suburban landscape itself as the source of the vaporizing effects that Fiskin achieves in the darkroom. These pictures require no pre- or post-production manipulation; the artist only needs to stand witness as another house is pulled from its tidy row like a rotten tooth. Divola has spoken of this and the related “Vandalism” (1974-75) and “Zuma” (1977-78) projects as signaling a concerted neo-realist turn in his practice. The Robert Rauschenberg influenced ‘flatbed’ approach to image-making very much in vogue during his student years at UCLA — where found image fragments are spontaneously joined in studio in a photographic approximation of the painterly process — is discontinued with the dawning realization that, in LA, whatever one points one’s lens at is always already montage. The landscape is itself a composite image; every individual part of it — the buildings, the plants, even the people — is sourced from other images and other contexts, excised and imported as fragments, and then rearranged upon a pristine ground of desert sand.

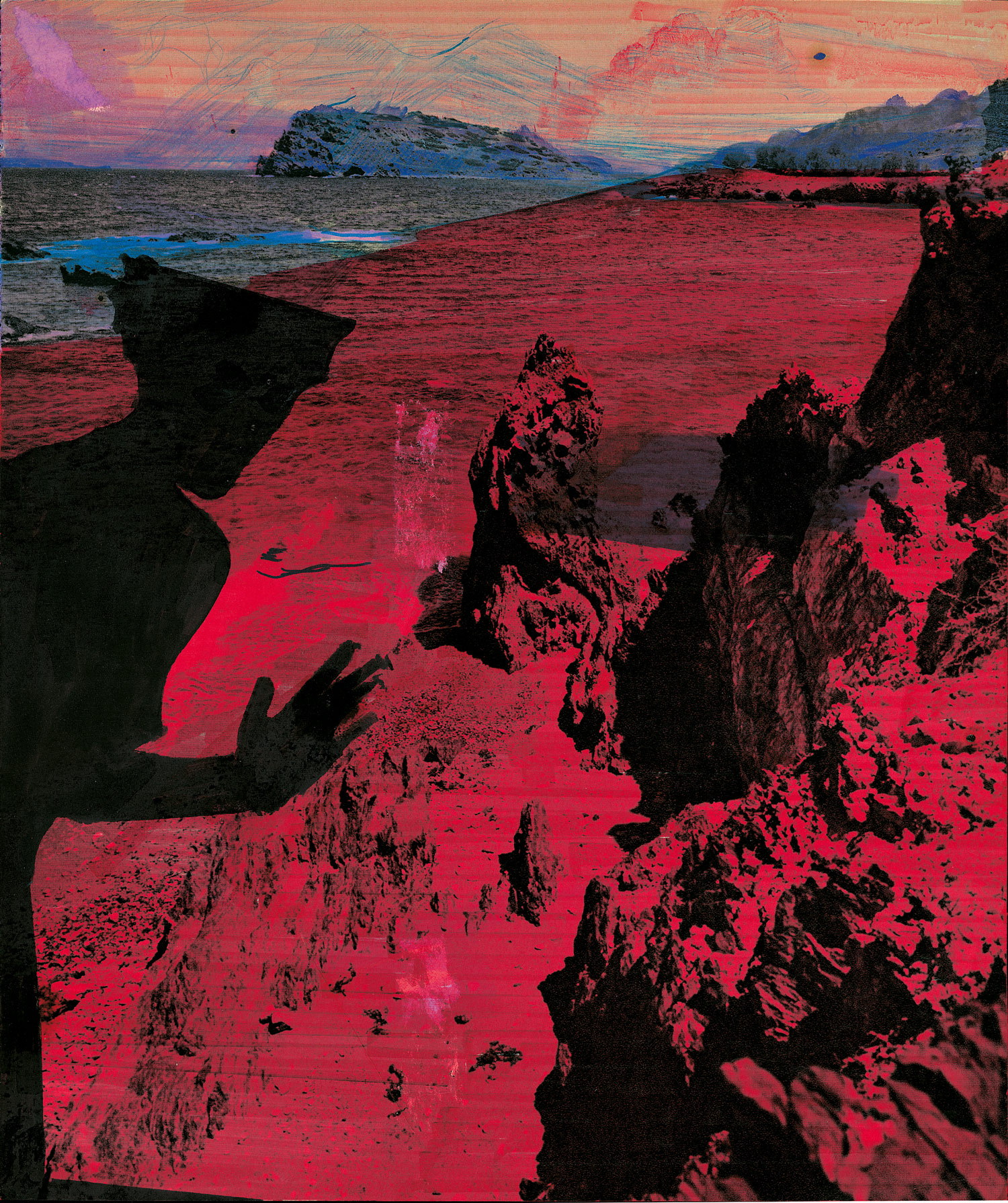

In the increasingly ‘tricked-up’ work of a younger generation of LA artists, whatever resistance the city as image once provided to the image of the city finally gives way. The built landscape becomes indistinguishable from the fantasy landscape conjured up in our collective psyche, hence Reyner Banham’s canny designation of our sprawling suburbia as “plains of the id.”2 Accordingly, in Amir Zaki’s 2005 Despalloc — “collapsed” spelled backward — we see a cliff-side home folding in on itself and then again unfolding before our eyes. Shown on a flat-screen monitor as a scrambled succession of individual shots smoothly dissolving into one another, the experience is profoundly disorienting. The viewer searches in vain for a spatio-temporal anchor around which to sequence these images as narrative, while remaining just as unable to simply give in to what would otherwise appear as a fluid abstraction. Every detail of its wood, masonry, concrete, steel and glass construction is rendered with utmost clarity but, at the same time, this house seems as weightless as origami.

Like Ruscha, Fiskin and Divola, Zaki has trained his sights upon domestic architecture as the very emblem of solidity and rootedness, only to literally undermine these same qualities. In some of his best-known photographs, the cantilevered supports that allow hilltop homes to jut over sheer drops in the interest of an unobstructed view are digitally erased, leaving the structures suspended in air like those cartoon characters that first have to recognize that they have stepped over a precipice before they begin falling. Shot from below to maximize their precariousness, we sense the full weight of what is due for imminent collapse — this, at least, is the ‘realistic’ assessment. But the up-turned angle also confers onto its object an heroic destiny, the house becoming a launching pad to the stars.

If the noir Helter-Skelter school of LA art conjured up its paranoid fantasies within the space of an extreme isolation, the Gothic enclosure, then this might be seen as a counter-tendency, one that is not so much social as hostile to privacy and to the cultivation of inwardness that it enables. Having leveled every obstruction, the gaze of the artist pulls back to survey the totality. Ships and planes and the views they afford of the city as a distant skyline or shimmering grid are ubiquitous fixtures of contemporary art. In the photographs of Florian Maier-Aichen, we transition between these as between shot and reverse-shot in film. Like the house, these vehicles are interior spaces that frame exterior vistas; like the car, they are narrative devices; and if we think of the camera itself as an extension of the mind, then these are all further extensions — extensions of extensions. At the extreme, however, our sight-lines are stretched so thin that they snap. One thinks of the vertical architectonics within which Gaston Bachelard secured the “life of the mind,” progressing from the sinister foundations to the sublime pitch of the roof.3 Here, instead, we contemplate the consequences of a lateral, scattered, homeless imaginary.

The tiny insect shapes that Soo Kim cuts out of her photographs of LAX and other transitional locales are like holes punched out of the fabric of the real. At the same time they echo the swarming motions of an anonymous nomadic public, having only just touched down or preparing again for lift-off. The sci-fi perspective on the city is fractured, continually crosscutting between a multiplicity of observers, and cohering only in moments of perceived threat. As with all those Irwin Allen productions from the ’70s — The Poseidon Adventure, The Towering Inferno, Earthquake, etc. — and their remakes, disaster is here recognized as an organizing, narrative principle.

Witness the “Garden of Eden on Wheels,” an exhibition of mostly local mobile-home wunderkammer at the LA Museum of Jurassic Technology, their obsessive-compulsive displays of depression glass items, ‘homey’ linens and jewelry, etc., all haunted by a hyper-awareness of the great eschatological count-down clock. Or else, Andrea Zittel’s ‘escape vehicles,’ which do for abstraction and modernist design what those more prosaic trailers do for Midwestern kitsch. In LA, our Mecca of rampant consumerism and commodity fetishism, it is both surprising and perfectly appropriate that we should always be thinking of the bottom line: what is worth holding on to through the end of the world.

Zittel’s home in the High Desert is the acme of spare, survivalist chic. Merging the streamlined ergonomics of Peter and Alison Smithson’s circa-1956 House of the Future and their exercise in post-nuclear bricolage, the so-called Patio and Pavilion for the “This Is Tomorrow” exhibition, also from 1956, it is a mini-museum to the science fiction imaginary as such. In its gallery display form as the A-Z Homestead Unit (2001-2005) it remains almost empty; save for a J.G. Ballard paperback ‘left’ on the night-table, it is a ‘blank canvas’ awaiting the buyers’ objective input. At the same time, this asceticism serves to remind us that the world of the future is typically one without objects. Of course, the house is itself a beautiful thing; much like 4166 Sea View Lane, Jorge Pardo’s Highland Park residence, Zittel’s is also a ‘house-that-is-also-a-sculpture,’ but it is a very different kind of sculpture. Consisting of a compact, lightweight and collapsible skeleton that can accommodate any number of different ‘skins,’ it is changeable, transportable, and even, in theory, disposable. A ‘collapsed/despalloc’ architecture of situations, it begins to implement in actuality the fantastical propositions of Amir Zaki’s imagery.

The desert is the ideal context for these lifestyle experiments, at once apocalyptic and utopian. The trek from LA’s sprawling suburbia, via congested freeways, into this empty expanse of sand and sun cements the original connection between the sci-fi genre and travel literature. This really is a voyage to the end of the world, or else to its beginning, the windshield framing views that are simultaneously redolent of medieval painting and the pulp paperback covers of Isaac Asimov novels. Between commodified pop cultural novelty and biblical arcana is exactly where Anthony Burdin’s Voodoo Vocals (begun in the early ’90s and ongoing) take shape, these cut-rate conflations of the road movie and rock video that have him filming himself while driving while singing to tapes of himself singing while driving, and so on. This too is ‘very Ruscha,’ but with a Robert Smithson twist, as if the straightforward orientation described by Every Building on The Sunset Strip were pulled into a recursive, looping knot. In the end, the music and words will be worn down to a mid-tone buzz, somewhat like the uniformly gray sand that is Smithson’s figure for entropy. It makes perfect sense, then, that Burdin should also wind up in the desert; in his Desert Mix, this once exuberant performer films himself trudging through those same gray sands, increasingly exhausted, amnesiac, unable to utter the names of the things he passes.

Building junk totems as s/he goes, marking the landscape with body fluids, the artist as feral drifter is the first casualty of communication breakdown in times of crisis. Sterling Ruby’s Transient (2004) amounts to an object/abject lesson in homeless art, and much the same can be said for the jarringly mismatched assemblages of Rodney MacMillian, Mario Ybarra Jr. and Aaron Curry, among many others. The disparity of their materials bespeaks the dissolution of the self forcibly separated from its chosen objects, the things that identity is built from, and making do with whatever is left over. Lacking privacy, a space within which to literally ‘collect oneself,’ subjectivity spills out while also indiscriminately absorbing everything in sight. The redundancy that Smithson notes while surveying the abandoned industrial landscape of Passaic, New Jersey, through his Instamatic camera only to find the picture already made — “like photographing a photograph” — is exacerbated in LA.4 All the more so in the desert, where flatness, surface and grain come with the territory, and we can imagine ourselves as coming with it too, or else on our way out. But this is no longer the great lacuna that Michelangelo Antonioni envisioned; in our digital age, every grain of sand has a will and a purpose.