Rindon Johnson’s work is as much about poetry as it is about presence. Poetry, in how the American artist uses words to turn meaning on its head, and presence, in how he relies on an array of forms that often mean the viewer is the most immediately identifiable, consistent thread in an exhibition’s narrative arc. Johnson writes extensively and sculpts confidently, using metal, cowhide, glass, Vaseline, and virtual reality, among other materials, to examine and manipulate the prismatic reflections of self in various parts of life’s architecture. In all its forms, his work seems to invite speculation and expose minor but crucial malfunctions in the form of contingencies, glitches, and misunderstandings; these in turn make way for new meaning. Viewing Johnson’s work tends to evoke a feeling of gentle dislocation, and rarely does it seem that expression per se is his main goal in making. Rindon and I met amid an endless pandemic, now in its third spring, to speak about formats, feelings, and life as the ultimate artistic process.

Isabel Parkes: I’m struck by both how fluidly you move between different media and how frequently you return to language. Can you talk about how language as a structure does or does not serve you?

Rindon Johnson: I think over the last years, starting in about 2015, I’ve started to better understand how words fail us. I’ve become more aware that as we are each constantly moving through different selves, language largely stays the same. I find myself asking how it is possible that one word can hold a meaning today and then have a completely different one tomorrow. I don’t believe language can hold it at all.

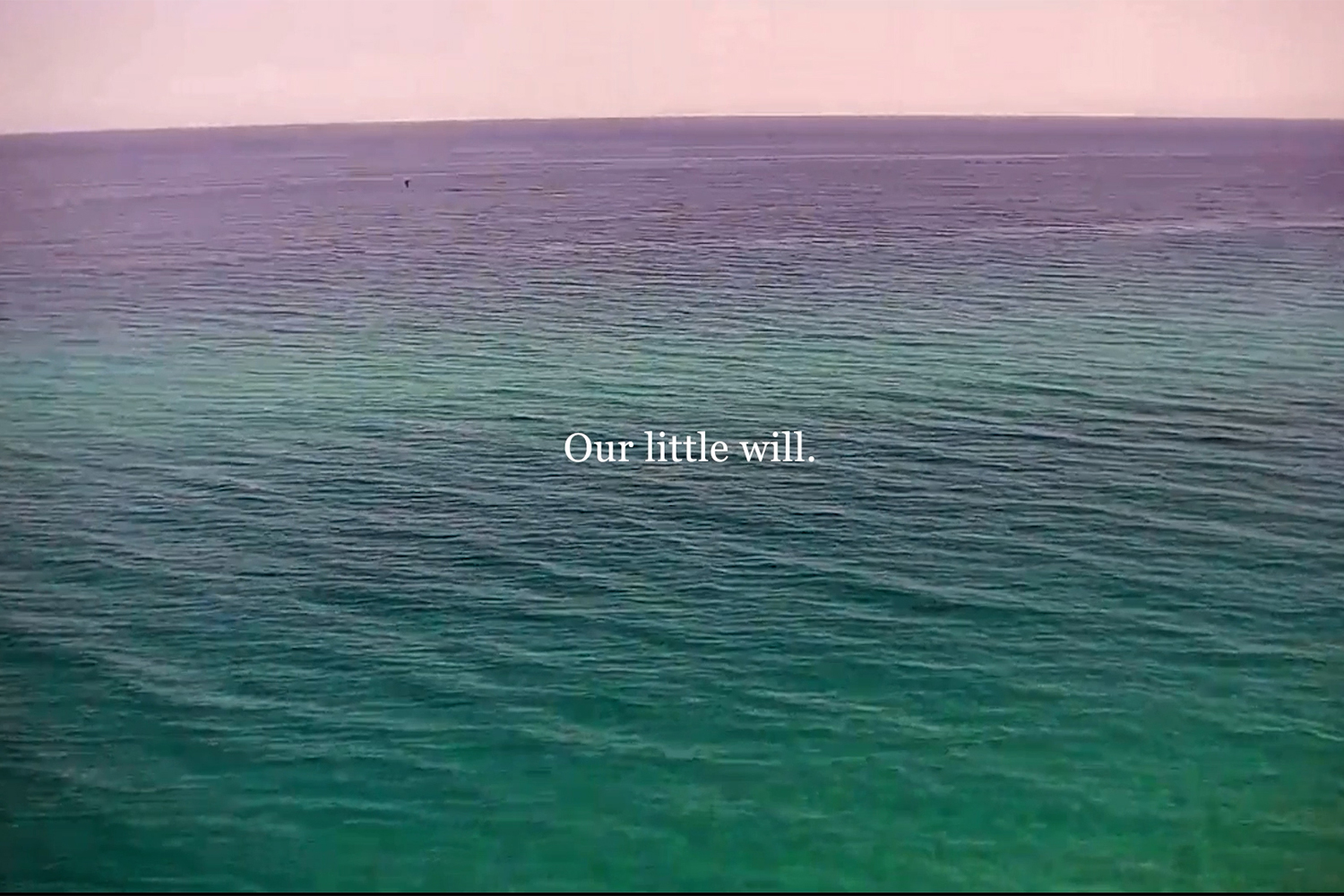

I love it — or at least I find it interesting — that we’re grasping for something in language that refuses to be grasped, something that is slippery and useless. I understand language as a stand-in for the impossible task of translating emotion between beings. Somewhere along the way, I realized that there is nothing the matter with language, but that language is itself the matter. Because language is the matter, although it is impossible to keep in shape, language-as-matter represents a failure. In that failure, in that language, we find ourselves communicating. It’s a constant back and forth of attempt, failure, attempt, failure. I have rooted my work in language over the years because I find that the way you define a word can keep tumbling in on itself. I consistently hope that I might make something endless that functions at the level of words, and that holds meaning both now and later. No word can hold a person, yet we desperately try to get the word, to get the person. It’s the best we can do.

IP: As you describe language’s inadequacy and its contingency, I’m thinking about your video The Dog is the Brother of the Fox (2020). That piece really captures the mutability of language.

RJ: That was a weird one. I secretly — or rather not so secretly — watch a lot of livestreams, especially during the pandemic, and I often record them. Livestreams feel like sites for never-ending poetry, where events are just occurring, free for anyone to view. As I was putting together that particular film, I remember finding the title, which originally comes from an Iranian proverb, in a documentary. In the same documentary, a general used the expression when speaking about ships that were being built in a certain part of Iran. As I understood it, the insinuation was that something seemed good like a dog but was actually just as bad as a fox. That got me thinking about the idea of subjugation, and of how the dog is a subjugated thing. By contrast, the fox is liberated and free to be naughty, to do things we don’t understand. I found it perplexing that the dog is a creature we generally believe we can control, but is just one step away from something that would steal our chickens.

I probed the thought further and things got more confusing as I started to be free with the logic of proximity, and I began to move the words around to explore possibilities. At the same time, I was thinking about the temporal aspect of the experience: it’s 7 a.m. in Florida, 3 p.m. the next day in Japan, yet it’s the same time and same moment that I and others are experiencing this language unfold. The video I made is about the constant overlaps of language, but it’s a work that still confuses me.

IP: Can you say more about your interest in simultaneity and livestreams?

RJ: Funnily enough, while I was completing my MFA, I was kinda obsessed with livestreams, back then of bears at Katmai National Park in Alaska. You can just watch bears doing their thing, which makes for the most non-

consensual act of watching there is! We’re just watching these animals, some of the craziest predators on the planet, try to catch fish, and they’re not very good at it. I mean, I’m a bear, I have pride. I don’t want people to know that I miss the salmon 80% of the time.

IP: It’s interesting to hear you describe live streams as non-consensual, also in relation to what you said about the subjugation of dogs. I find that several of your works reveal a deep sensitivity for interspecies power dynamics — for example, also in how you portray cows.

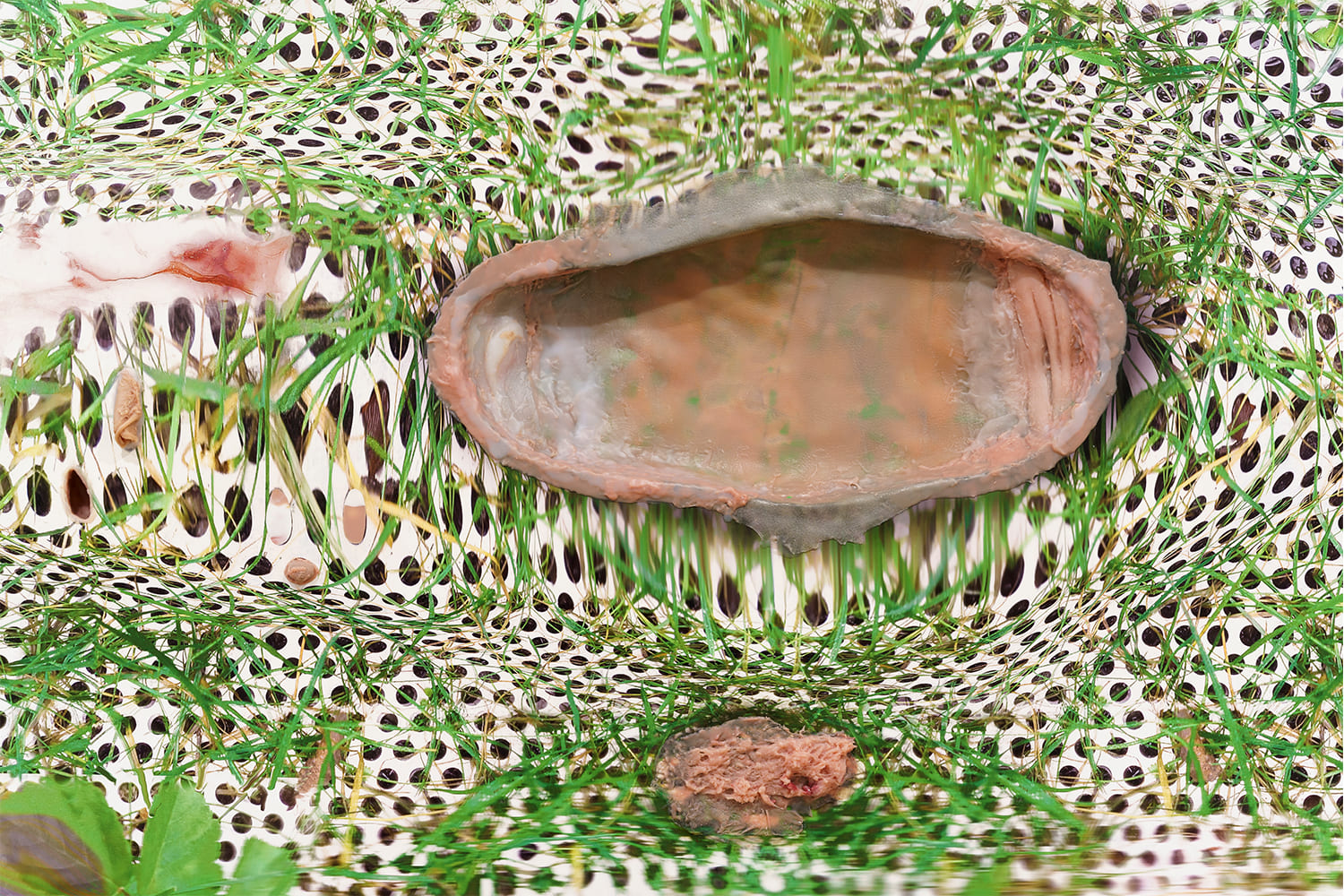

RJ: Totally. I say this quite a bit, but my practice is basically the culmination of my interest in byproducts. I’m a byproduct and I want to know about other byproducts. What I find interesting about the cow is that — to zoom out briefly — when you commit yourself to a particular thing, that thing could be anything, actually. So, in my specific act of committing to the cow, I am both not committing to the sheep or pig, and, at the same time, committing to all of them: all animals that share a sense of confinement.

I wonder about their confinement in relation to my own confinement, particularly in relation to the kind of capitalism we live under. I consider myself as confined by capitalism as the cow is confined by capitalism, yet my day-to-day experience of liberty — of who’s subjugated — is consistently altered; the cow exchanges its body for living. What do I exchange my body for? It all really sends me for a trip.

IP: Can you track the origins of this notion?

RJ: My interest in the interspecies conversation started many years ago, when I stopped eating octopus out of a discomfort for their intellect, and a friend of mine was just like, “Dude, that’s stupid. Either you stop eating octopus and you stop eating everything else, or you recognize that your decisions are futile.” I realized that what I was doing was out of a sense of comfort or rather discomfort, and that led me to observe that I’m never actually comfortable, that the things of capitalism are never comfortable. I felt aware of an endless futility.

It could be the cow, it could be a dog, any of these animals that we’ve chosen as the ones to survive alongside of us and that are as intelligent as we are, likely more. Time and again, we choose to ignore intelligence and continue to use other beings. I ask myself, what parts of our own intelligence do we ignore to use ourselves or position ourselves in service of the market?

IP: Can you tell me about the work you made for this year’s Whitney Biennial?

RJ: I knew I wanted to make a series of large, multipaneled works, and I think these paintings are the most refined my chance-based process has ever become. I conceived of them as cows on the horizon, but they’re also significantly informed by various artists that have impacted me for years now, among them Amy Sillman, Helen Frankenthaler, Matisse, and especially Mary Lovelace O’Neal, whose interest in whales has set me up for the work that this series is bringing me to now.

It’s important to me that four, not all eight panels, are there; that you encounter part of a whole. The color blue and its mysticism spins through the presentation as a way to explore the specific history of color and a broader one of painting. In my obsession with the history of American abstraction, these works also undo themselves through an obsession with material — the material being cow as well as indigo. All four works went in and out of the indigo bath, in the sun, out of the sun, for months; they are heavily processed. They also incorporate new forms and my new interest in varnish and reflection. Over the course of the exhibition, the works’ reflectivity will grow more intense as the leather builds up. The idea of a work reflecting you, back at you, without being heavy-handed, is something I’ve been approaching for a while.

IP: I find that your work fuses hyper-specific fragments with broadly classical forms, like nudes or landscapes. In that regard, I’m curious to hear how you reflect on the formal qualities of your work and the wide art history that you’re part of.

RJ: I’m obsessed with art history and always have been. I would do acid at the Met to feel connected to art history in a way that is, in hindsight, pretty silly. Really, why do I love this canonical space that excludes people that look like me? A nicer part of me thinks, well, you can’t help what you love. But yeah, your observation on landscapes, the nude, all this stuff, absolutely, it’s in there. My mother owns a gallery and I’ve spent my life in museums. I find that if I use forms that are legible as artworks, then at least some of my ideas, wanderings, or misunderstandings can make sense. I view form as a container, almost like a Trojan horse.

IP: I see self-portraiture as another recurring form in your work.

RJ: Definitely. I think some of that stems from an awareness that I have only one vantage point and that I can speak from it comfortably, then hope that it has enough inside of it that my specificity can become universal. I don’t fully get self-portraiture, which is part of why I am interested in it. How do you recount the things that have occurred to you? It’s amazing what people say about how they recount their own existence, because for some, it’s completely sonic: sound is enough to jar them into a memory. I’m curious about how to play with that, how to mess around the senses. I also struggle with portraiture because for a while now I haven’t thought I’m the type of person who can show the black body in my work figuratively. I think I disagree with it. I think that a black body in a figurative work might be the reselling of that black body, in which case, I don’t want to participate. I’m not interested in selling any bodies. That’s a thing, that’s a question too: I won’t show a black body, but I will sell a cow. I challenge myself and I’m confused by myself, but I’m okay with that. Portraiture remains an enigma to me, and I guess that’s why I keep going with it. It’s the same thing as from my one vantage point, not far from how I engage with virtual reality. I’m like, “What the fuck is this?” And I guess I just have to keep going until I get an answer.