If writing is the mother of the comatose archive,

I wonder if exhibiting could be the rehearsal hall for a brief spell of somnambulation.

— Huang Jing Yuan, Right to Write

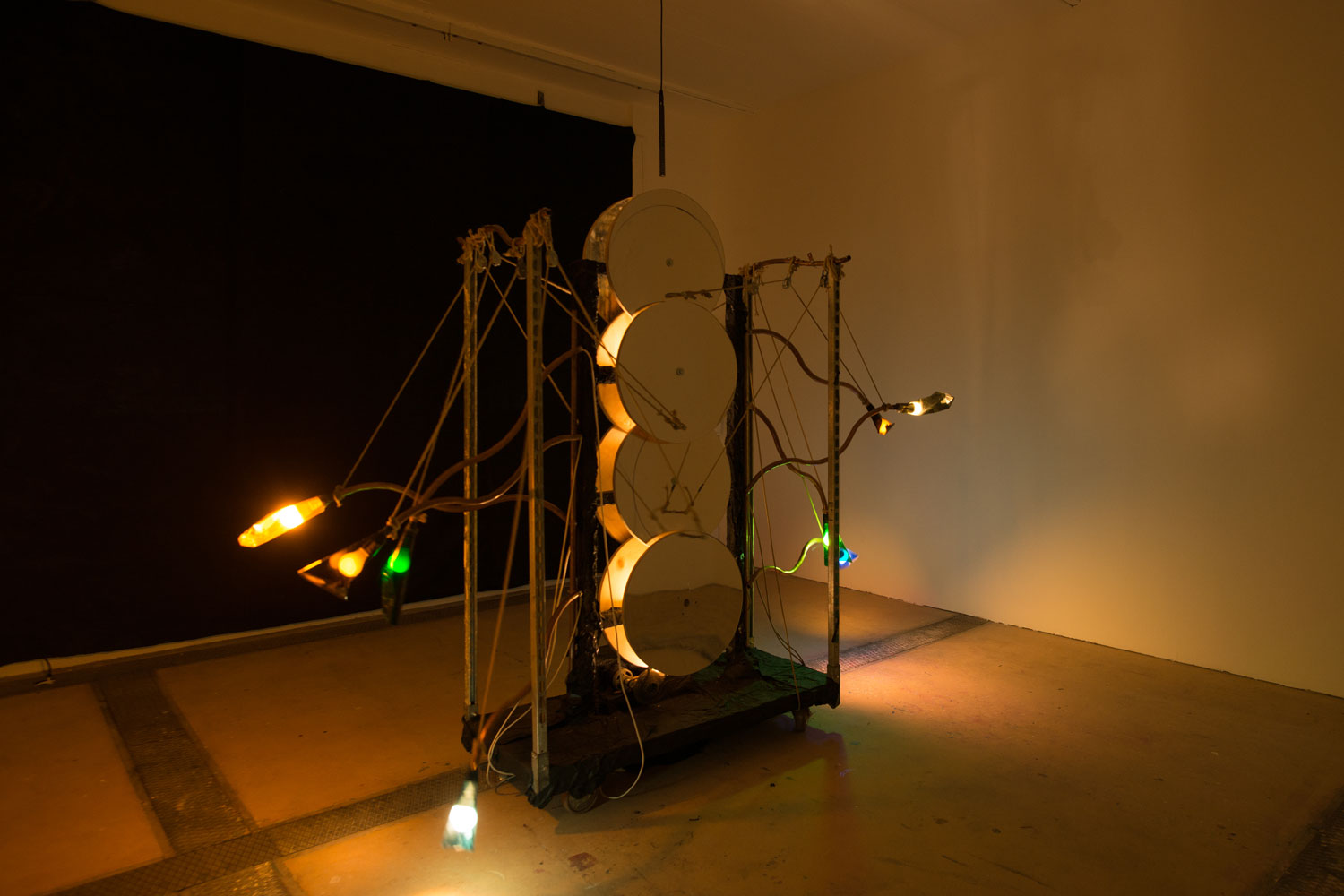

Tucked away in the left corner of the third floor of the Power Station of Art in Shanghai, between Francis Alÿs’s video Rehearsal I (1999–2001), in which a Volkswagen Beetle continues its Sisyphean exercise of ascending and descending a hill, and Wu Chi-Yu’s video Reading List (2017), in which the underbelly of transnational capitalism incisively rescales itself, is another “third world,” Huang Jing Yuan’s own hybrid gallery, Right to Write (2018). Her writing room, a co-writing space with three of her own paintings interspersed with calligraphic pieces by others, some close to calligraffitis, is situated between those two videographic loops of the modern, post or hyper. Set up like a construction site under construction, Huang’s work is — or inserts itself like — a ruggedly analog, analogically layered contrarian zone in between, where expressively inscribed surfaces are grafted, seemingly randomly, onto the inner dividers of the space such as PET sheets, semitransparent PC sheets, tall green curtains, long canvases, etc., turning the whole room into a half-closed exit, a passage out of the textual site into another sort, sortie, of third-worlding.

How so?

So I am walking in, wandering through this dimly lit, shack-like choral site, a sort of khôrā (χώρᾱ), the territory outside the polis also rooted in it as an invisible receptacle, a housing house. The site is sliced and staged in five “steps on the ladder of writing,” as Hélène Cixous might say: (1) an alley-like corridor at the entrance to (2) a center-stage-like living room semi-open to (3) a backstage-like backroom that, with a set of three display cabinets and chairs, whispers “this is an archive” to (4) a cave-like bedroom long and narrow, where five books on a small plastic table party with nineteen balloons crowded around the corners, all invited by two pillows at the end of the room, a silhouette of which is visible from (5) the reception, also an exit from/to Wu’s darkroom, the only access point.

So this port of dreaming is portable and porous, an ex libris, where the dreamwork, part of the book, also departs from itself, with the x of ex, its own outwork. In an exhibition leaflet, Huang writes:

The project tries to synchronize different kinds of isolation, to create a narrative for segregated worlds to mirror each other (no, they don’t explain each other, nor can they save each other). It invites viewers to ask: What is the ordinary Chinese person’s experience and expression as they negotiate the vortex of changes and ubiquitous inequality? What do these instances of picturing the world say about the time we are in? How may we empower ourselves when faced with the past and the reality in front of us, and the world yet to come?

The layout that literalizes this democratic, cramming, clamoring, and choral spacing stays circular, which renders this documentary project multilayered as well as multilingual, and its discursive realism materially imperative: it is what it is. What you are entering and exiting into at once is a transient cocoon for the dispossessed in transit that can be — and was — constructed in just a couple of days. An interstitial crossbreeding of the words and the worlds across the board, a concurrent sighting-citing of the contingent “coming-together” (Huang’s words) on-site of what matters materially: that is what is happening in this counter-show of the sociopolitical hierarchy and intricacy of existence in China.

Held here is an unmanicured display of the messy, messily precise assemblage of wor(l)ds. This democalligraphic utopia is littered with not only letters — a kinetographic mix of Chinese, English, German, slogans, clichés, quips, among others — but an eclectic array of homey materials such as florescent lamps, blankets, foam padding, and vinyl sacks.

There are scraps on the bedroom wall, including a sheet from a college-ruled notebook bearing the logo of Beijing’s Tsinghua University over which an un(der)recognized migrant worker-calligrapher, one of the fifteen invited, has written his lines quite elegantly — a sign of education. The letterhead signifies something for the letter-writer otherwise insignificant; see how such a socially significant space, Tsinghua, one of the highest seats of learning in China, was used as an interface, as a practice paper. What makes this otherwise ordinary note noteworthy is the psychopolitical incongruity between the two different use values held by that inscriptive surface, one utterly functional and the other overly symbolic. Those blank lines inviting aspirational inscriptive practices routinize the small, private pleasure of playing on a (reproduced) public property, which would also be inconsequential — or is it? Such a transposition does seem to effect transvaluation, however micro. In this shabby dreamscape, like a roomy coffin, the glass ceiling could also shelter the nanotransgression of a writer enjoying his own calligraphic (with)drawing, a room of his own.

So what?

Looking back, what initially attracted me was this concept behind the current edition of the Shanghai Biennale: “proregress,” a curious head-scratcher from poet-painter-playwright E. E. Cummings, whose works countered the ideology of progress, the discourse against which one is supposed to feel under- or over-developed or still developing. At the Biennale, the curatorial team has brilliantly recontextualized proregress as the correlate to a mystical dance step, 禹步 (yubu), in the ancient Daoist ritual: a twisted bi-directional movement composed of stepping forward once and backward twice. In its contraction, proregress holds together the scrambled eggy steps of choreographic time across this chiastic zone of modern/postmodern/spatiotemporal contemporaneity and simplexity, “actually absorbing,” as the biennial’s chief curator Cuauhtémoc Medina aptly puts it, “the weight of this moment in time,” all the complications and entanglements that time itself seems to endure now and nowadays as if forever.[1]

Huang’s Right to Write is, again, an illuminating case in point, a vibrant work in proregress. An imaginatively populated and democratically polyvocalized why-not, this choral space for an archival future honors without trying to harmonize the life experiences of the xiaorenmin (xiao small, renmin people as in People’s Republic of China). She choreographs their microsignatory gestures by unleashing and rechanneling their expressive, and at times lyrical, potentials — through and toward the collaborative platforming of their auto-ethnographic or auto-documentary work. This mode of socially participatory art is literally process-oriented since the work in network, at every step, materializes through co-creative dialogues; the artist is there not to validate or authorize but as a sort of midwife. As a series of counter-proscriptive and co-scriptive experimentations in open-ended collaborations, Right to Write (or to read) becomes a site-specific, descriptively proregressive exploration and analog data-visualization of a polycentric democalligraphic utopia — pregressive, even (walking along as if ahead/around/back and forth).

What is the condition that makes progressive and regressive moment, itself so ambivalently (with)held, possible? Such a Kantian quest could be recast in the spirit of daoist proregressivity too: pushing for “pregressing,” I’m transporting this idea that dao (way/route 道) is “in the making” (道行之而成), not simply made, as in the second chapter of the Zhuangzi (莊子), which showcases the egalitarianism of Daoist philopoetics. Pregress (道行), a Daoist practice of “following” Dao, is an instantaneous auto-spacing and pacing, an improvisational performance per form (of its own), which is not to say that the pregressor is an “avant-garde” walker or mover, for she “advances” not. Rather, yubu-ing more or less, she lingers with her neighbors and moves with or without them, as necessary, while passing through various walls, connecting the dots here and there. In short, pregress points to choral timing and spacing itself — or herself — embodied in its vehicular dao, namely, passages and processes including protocols in motion.

So why bother?

I am interested in further resemiologizing the eco-echo-spacing mode of socially engaged art and articulating such in a more site-specific, sinographic set of idioms. I focus on the dynamic ambience of Huang’s translingual and social dreamwork, inseparable from her teamwork as well as her own artwork, because there I see how the pregressive level of its praxis also mirrors and reinforces its formative bioenergetics (qi 气/気), not just its morphology; this way, the framing and the framed become reciprocally generative.

Perhaps this is how a Daoist sensorship works as a mode of (counter-)demonstration too. See how a critical intervention happens through and concurs with a counterbalancing perceptual move: observe the convoluted yet stabilized shaking, the shake-up in the middle of it, swift and quiet, potential or actual, literal or metaphoric, the phenomenological and material presence of the other move, its necessary messiness, however mini or contained. What prompts all that jazz, this network of collaboration, if not the work of netting and knitting per se? Huang’s structurally contingent, makeshift production of proletariat calligrammatology through socially synergetic artistic practices presents a matrixially autographic “X” without presetting or representing “it” (X) while proregressively renewing each one in the form of auto-archival backtracking and recasting.

Involved here is a constant passive-active glancing back and forth, the active gaze of the artist, also visually metonymized in the two (pair-able) paintings of a tight-lipped, stubborn-looking little girl at the back leading to the reading room of the house (Next to the water 01, 2016) and a middle-aged woman in front framing the living room, who looks like a world-weary Chinese Athena today (Next to the water 03, 2018). “If writing is the mother of the comatose archive,” as the artist writes, “exhibiting could be the rehearsal hall for a brief spell of somnambulation,” where that girl turning around to look at you, that haunting one, could be you, any one of, in the past or future, just as that lady resting there for a while in the middle of some group tour could be anywhere, anyone.

Further telling is the position of those two paintings triangulated by one in between, an image of a (pregnant?) girl and a boy holding each other (Next to the water 02, 2017). The pregressive circularity of and bordered connections among three female figures, only visually signified here, functions like an ur-text (of contemporary China in the making?) that seems already fragmented as if pre-indexed. By proactively staging counterfragmentations as a series of shout-outs, however small or seemingly secondary, Huang’s anarchive, along with the pregressive vacating of its own vocal subjectivity, effects the autocuration of an eclectically free “we,” the sort of intersubject not as strongly present in more elitist and individualistic “other Western” figures such as Emily Dickinson or Walter Benjamin, those also focused on the fragment(ed)o(nto)logy of documented lives.

What would those writers from other shores have seen in this “other” writing?

The rustic, quietly irreducible residency of the graphic bodies dynamically distributed and detailed in small pieces of papers and big pictures held together in their chrono-diverse proregressivity, pregressively intensifies the very blurry overlap between the visual and the “verbal” which, in the case of Chinese characters, is close to visuo-musical. Right to Write as a right to play de-monolingualizes and re-quotidianizes the very norms, practices, and scenes of writing, and the artwork itself, the platform that looks but is not flat, unfolds through a serially inclusive, transformatively collective aesthetic democratization, especially an asynchronic reminification with other “Chinese characteristics,” of a Right to Write.

This could perhaps be one way to split open and empower alternative social (including socialist or is it now post-socialist?) tracks within China today, in and outside her hyper-controlled politico-economic landscapes and turbo dreams. This idea of a democalligraphic u-topia remains highly speculative and yet it is at least an idea. On my way out of the Shanghai Biennale, right past Museums, Money and Politics (2018), Andrea Fraser’s map of the US shown in China today, another visualization of the “verbal,” I thought, yes, “right: to write _____” alone together would be an idea — especially to write along with others in a corner room of ones’ own belonging to a stately house that used to be a power station, yes, power.