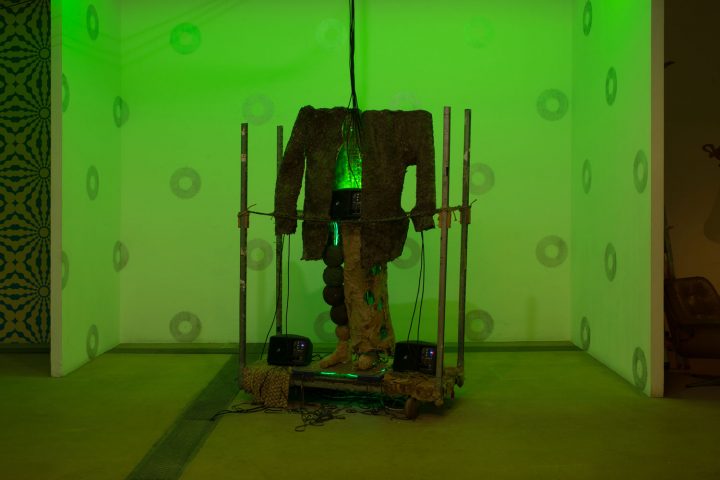

At the Centre d’Art Contemporain in Geneva, Tamara Henderson’s kinetic sculptures Sun Spider, Nomad, Sound Shepherd, Language of Mud, and Eye (all works 2018 unless otherwise noted) are strung around four rooms on the top floor like limbs of a single mechanical body titled “Womb Life.”

A web of copper cable flowing electricity to a hand pump meets a web of copper pipes flowing with water. These are the main arteries in Language of Mud, a sculpture, film, and fountain made using a kiln and clay body parts. Later, when the show is over and the veins run dry, Henderson’s soft sculpture Nomad will wrap around these clay fragments like an exoskeleton so the work can travel to Torino.

“Life is but a motion of limbs… for what is the heart, but a spring; and the nerves, but so many strings…”

—Thomas Hobbes (1651)

“Womb Life” is Henderson’s version of Prometheus, where life wakes up only to find it’s been attached to a wall. Chained to rebar, tied to some legs, cables, high heels, and a loose web of other attachments, her work extends outward, infinitely closer to the conclusion that life is simple until you take it apart. Henderson’s work vibrates on a fragile filament between art and life that often results in a chaotic sect of wrinkled poetry. Her life folds easily into her work. Isolated points connect briefly before being mulched into any material more pliable than prose, for example the clay she is seen kneading in her film Language of Mud. This film will be merged with five less recent films in a working process she describes as never-ending.

Meanwhile, in a curious operation, Henderson’s sculpture Sound Shepherd is in Geneva with a microphone still dangling in its open rib cage, quietly sending sweet, gentle sounds to a fountain next door. This calming ballad is as soft as the wind, and caused by a very light friction, a warm touch of electrical current down thin copper wire.

The following is an edited version of a conversation between Aaron Weldon and Tamara Henderson, held on January 11th, 2019.

AW: In your film Language of Mud, a man’s voice speaks about sinking into the mud, feeling the earth’s weight on your body and passing through layers of time.

TH: The voice in Language of Mud is a hypnotherapist named Marcos Lutyens, who is also an artist. The show is called “Womb Life.” In Los Angeles I took the ashes from [the sculpture] Scarecrow (2016) and used it to glaze the brain. The process of firing the body parts isn’t visible, and there is this period of waiting that is so much like pregnancy. Not looking but listening. I saw Jake, who helped with the exhibition, as the midwife and doula, supporting the life of the work. It was so beautiful. “Womb Life” is under the influence of having two bodies: two brains, two noses, two hearts, four legs. I had the sense my body was kind of extreme or something — two heartbeats.

In “Womb Life” there is [the sculpture] Nomad, and that system allows the body parts to travel without being damaged. I was thinking of an invisible umbilical cord; they can’t really be separated. The boxes are slightly larger than the body parts, and the soft sculptures wrap around to protect them so they are able to travel. I want to make an instructional work with those for unpacking them.

AW: Your work has been considered “automatic,” and I see that a bit less now. Auto means “self” in Greek, Atman in Sanskrit. Atmen [in German] also means “breathe,” and the mechanical sculptures remind me of a story from the Upanishads where all the body parts are sort of tired of their jobs and they feel they are being undervalued. One by one they go on vacation, and when they get back the others say, “Eyes, we really missed you,” and they all agree to appreciate vision. Then the breath decides it’s time to go, and just as Breath is about to breeze out the window all the body parts get together and ask it not to go. In Geneva it seems like Breath is considering a vacation.

TH: When I heard some of the sculptures aren’t always moving, it surprised me that I didn’t mind so much. That type of motion doesn’t seem the most important. Next time I show the movies, I want to merge them together on film.

AW: In the sculpture Sound Shepherd, I was wondering about the feet. I was trying to remember; it looks like your feet are not extremely big.

TH: That’s a portrait of Oliver Bancroft. I think you would love Oliver. Before I met him I was looking for someone to help with sound. I asked if he would be in my performance and he told me, “I’m giant and a bit disabled,” and I thought, “What? A disabled giant? Well I’m sure it will be fine.” He has a box that sends electricity down his leg to activate his muscles. I think about that a lot.

An essay by AARON WELDON will be published in the catalogue of the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement 2018, edited by Andrea Bellini and Andrea Lissoni, in June of 2019. His film with the National Film Board of Canada, Immortal Invisible, is set to be released in 2020.

Tamara Henderson’s “Womb Life” is on view at the Biennial de l’Image en Mouvement at the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève through February 2, 2019. It will travel to OGR, Torino, in June 2019.