It was the last day of March, and I chose the corner with the sage-green marble tables and white sofas at Soho House Berlin to wait for him. I wanted to see him come in, to catch the nuance of his mood, or his walk. I always like to notice how dancers walk (too cliché?). Anyway, I missed his entrance.

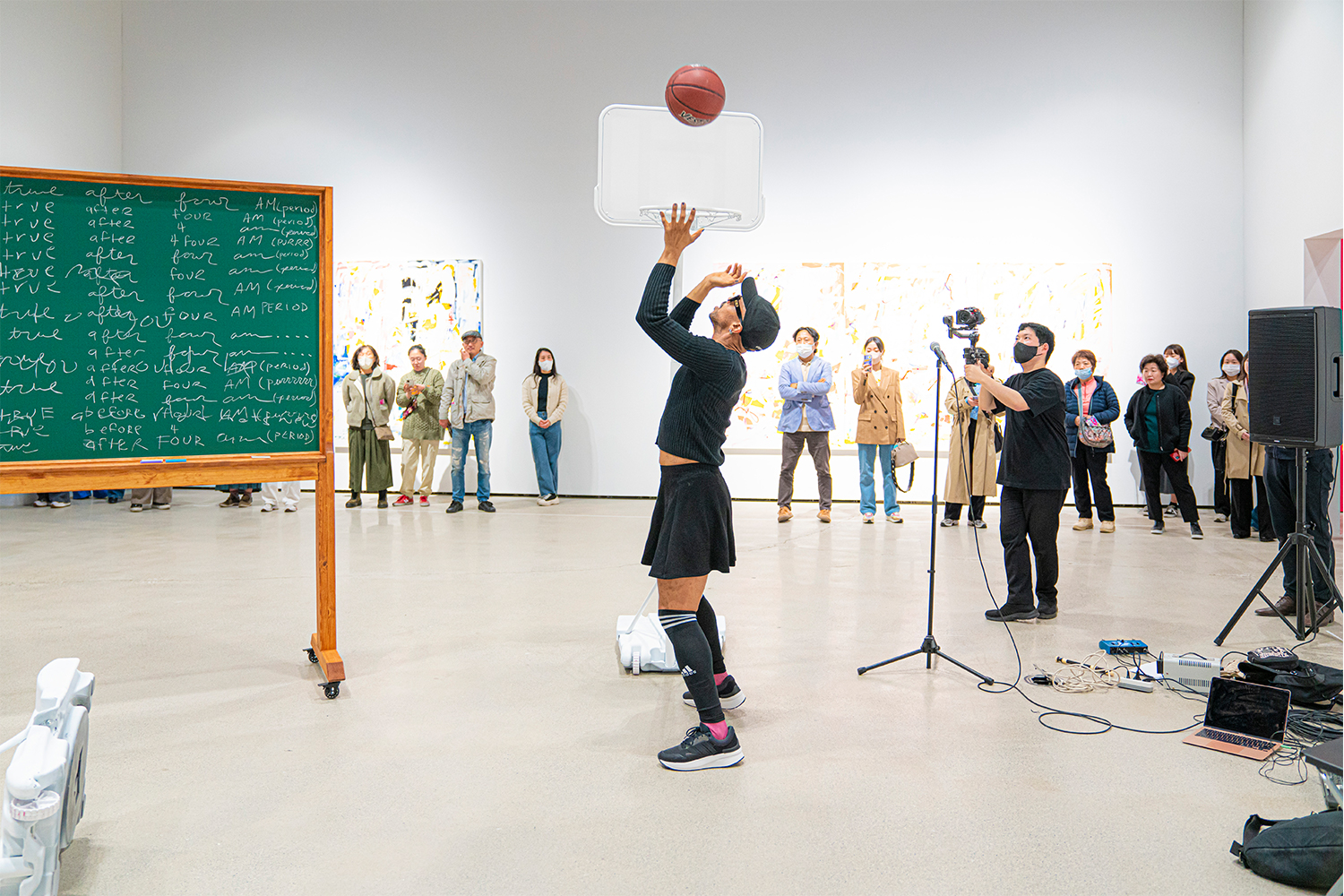

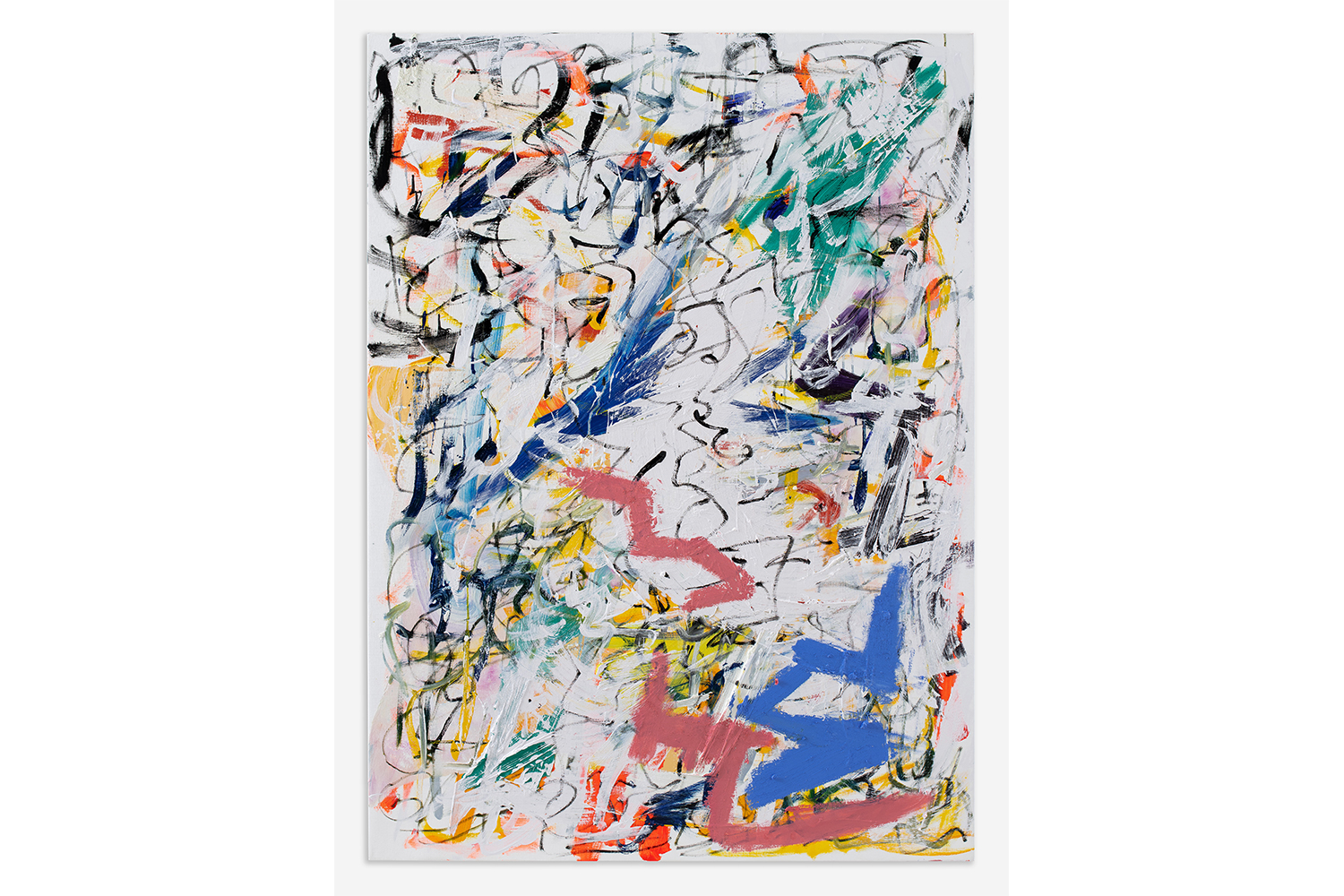

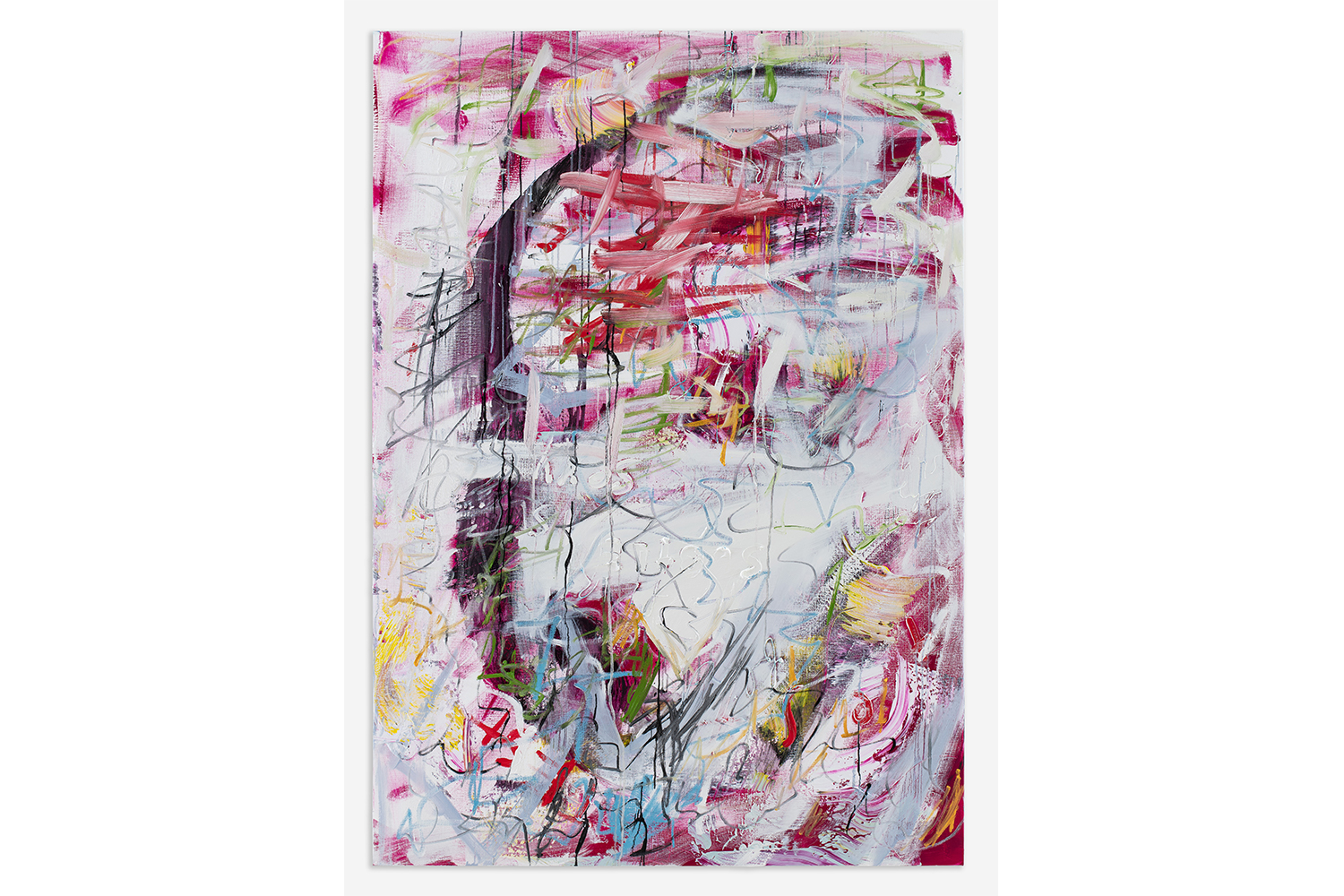

When I first met Richard Kennedy, in Milan last December, it was after seeing him perform the opera Zeferina (2022) at Peres Projects in Palazzo Borromeo. The exhibition also featured the three-channel video opera Read Patience (2022) and a series of paintings including Beneath the Wedding Veil, Micro Braid Baddie, and City Street Wall Beat (all 2022). Kennedy is an experimental composer, librettist, dancer, painter, and performer: in a word, an artist. He moves sinuously between languages, his output extremely natural and highly performative. At that first meeting I immediately noticed, through his semi-transparent pierced black shirt, a tattoo of Nefertiti, for him the “queen of the night” as well as the queen of the Nile –– and thus we discovered a common obsession. He explained to me how this icon, housed in the collections of the Neues Museum in Berlin, was a valid reason for choosing to live in Berlin. It is the power of history, its circularity, that determines Kennedy’s need to travel through it with his practice. He was introduced to opera as a child by attending dress rehearsals at the Sorg Opera House in Middletown, Ohio, and he absorbed its gestures and structural elements, which he then reworked by experimenting with participatory modes of activation based on queer African American experience. Everything about Richard Kennedy’s work suggests to me a kind of nonlinearity, a constant short-circuiting, including how he presents himself to the world: a talented queer African American with a tattoo of an Egyptian queen circa 1300 BCE.

On that spring day in Berlin, after abandoning the corner I had chosen to wait for him, we moved upstairs. Then, not sufficiently happy with the vibe, we decide to go together to the Neues Museum to visit our icon.

The conversation that follows took place over breakfast at Soho House, hours spent in the Museum’s Egyptian collection among hieroglyphics and sarcophagi, a vegan lunch, and a visit to the artist’s studio.

Eleonora Milani: Why is this work we are currently viewing at the Neues Museum, Relief: King Ashurnasirpal II and Genius (ninth century BC), so significant to you?

Richard Kennedy: I love this piece because it’s one of the first things that you see before you enter the Egyptian wing of the museum. It hits different when you enter a space only to be greeted by a queer representation from antiquity. Two male figures with earrings and long hair, one wearing a beautiful bracelet with a flower. One of them is holding a Telfar-shaped bag! That’s what initially drew me in on my first visit. I’m interested in how iconography travels through time. The energy of queerness and pleasure has survived the ages, and when I see these two I want to go where they are going. One of them is carrying a plate — an OG party queen perhaps? This relief of two mischievous figures, draped in celebratory, embellished, eccentric looks that blur the line between the masculine and feminine — it’s so Berlin to me, to go downstairs into the gay club, aka the museum space. It’s that connection that transports me immediately and tells us what we need to know.

EM: What do we know exactly about these reliefs? What are these hieroglyphics telling us about the power of these hands?

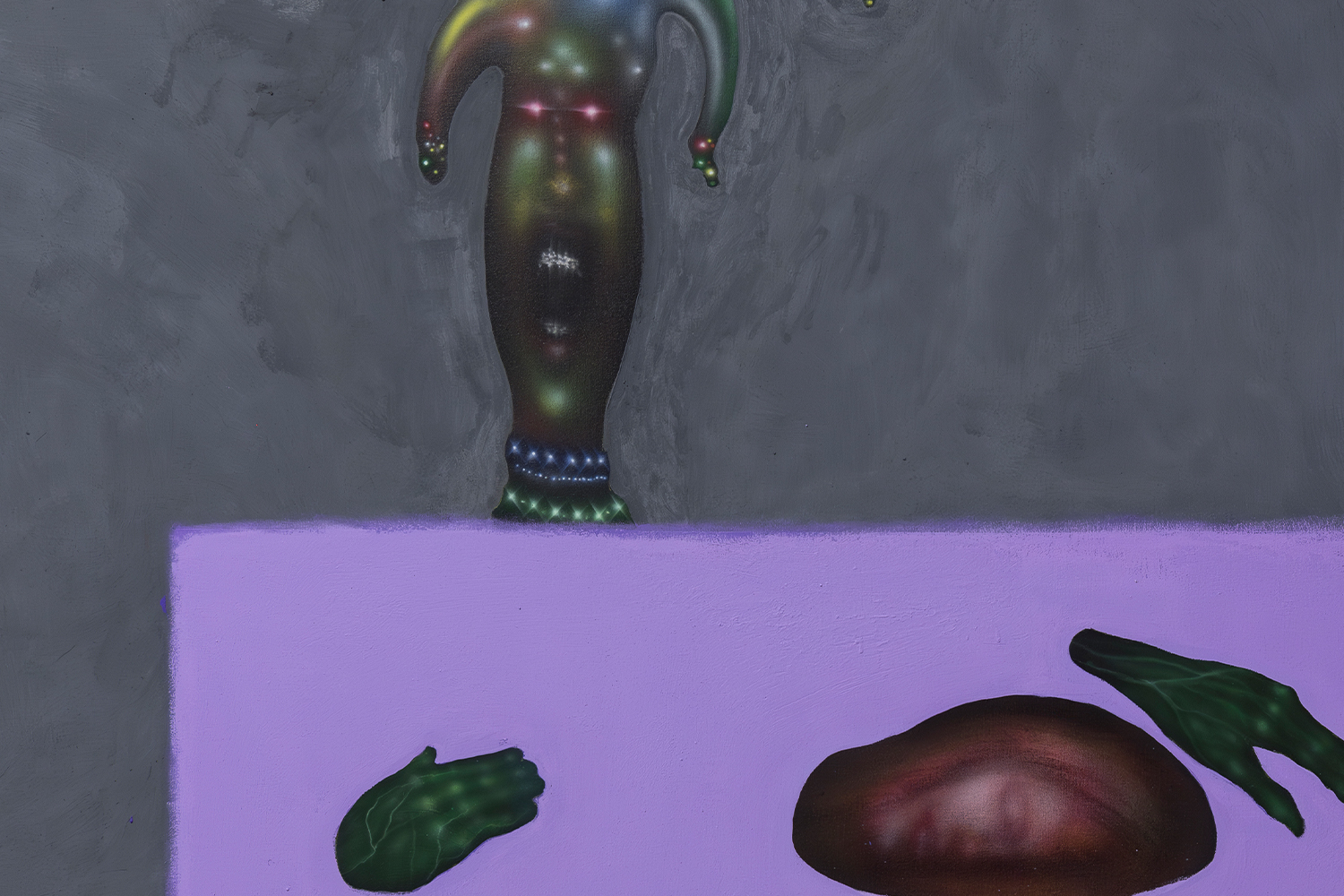

RK: All we know is what we can observe. We are left with pieces that we put back together over time, looking for more clues and access points to the past. The care shown in portraying the hands in these hieroglyphics stands out to me; they hold crucial information. The hands are shown reaching out, sharing energy or holding tension in the body. This 3D representation of energy makes me think a lot about Reiki. How have these phenomena impacted art throughout the ages? I am fascinated by how energy, ideas, and information are passed between hand and body, whether through a massage or something more profound. These hands built the pyramids! We still don’t know how they did it, but we assume they did it by hand. I’m always looking from relief to relief, from hieroglyph to hieroglyph, and trying to find that intelligence within myself — to look and almost will my hands to keep building.

EM:I think quite often of this idea of destroying eternity — I mean, destroying what is supposed to be eternal. The art of the present time is at risk of being forgotten. I think of John Boardman’s The Archeology of Nostalgia. It seems to me that time is always faced with nostalgia.

RK: I’m a nostalgia queen because I love old-world aesthetics. There was a different level of commitment to craft and an exact level of specialization. The body-mind connection is made concrete through the incredible abilities of virtuosic hands. It’s nostalgia that makes me asks questions. What’s the use of remembering when time is bound to forget? The digital age has sped up the process of becoming nostalgic. Trends come and go instantly. Eternity is an illusion.

EM: What is our real access to this heritage?

RK: For most, early access is through history books, the internet, and cinema. Since living in New York and now Berlin, I have been able to spend time with these artifacts. When I look at King Ashurnasirpal II I immediately think of Prince. The serpent on the head, the missing eyes, and the large feet tell us something, but what? Within the representation, there is also the vanishing of gender and the binary. Could this vanishing be what renders all eternal? Do we really have access to all that is there? I find excitement in these cycles of forever attempting to know what we simply cannot.

EM: So the projection of reality onto this artifact — it’s like everybody is experiencing it very differently.

RK: What if we experience it the same but comprehend the energy and symbology of the artifacts differently? I love archeology and its commitment to excavation. As I speak, I’m digging through my mind trying to connect what is with what could have been. We can see but not feel the magic; it is both familiar and mysterious. Energy doesn’t die: it leaves traces of something that once was — that still exists in the world. The Bastet statue speaks to this deep connection, transcending the human form and embodying the impossibility of an otherworldly experience. With multiple realities happening at infinite points in time, a variety of experiences around a single object of fantasy makes it more than just an artifact.

EM: When I think about your practice I think about nonlinear time.

RK: I’m obsessed with circles, and I conceptually engage with them in my work. I studied dance in undergraduate school, and we did a lot of “X” material — warm-ups that transcribe the body through the X. Placing that X (my body) in a circle (my work), I position myself to move like the hands of time around the circle, tracing the Earth with my body: a moving image of a Black Vitruvian Man. Creativity comes through me in spirals and defies time. The narrative loses its battery at the beginning of its journey and stops time. Applying layers of oil paint to build a painting requires a look beyond time. I often move forward to reverse and reverse to evolve, colliding into a future that is anything but straight and easy to follow.

EM: Let’s take another leap into the past, to your childhood in Ohio. How did you embrace this sort of archaeological dimension that has flowed into your work?

RK: Growing up in Ohio left so many beautiful traces and bruises on my soul. I was an inquisitive kid, and that has fueled me since day one. Growing up in Middletown, Ohio, I relied on my imagination to survive — I was constantly digging inside myself to create a new reality and doing all I could to find a way out. I abandoned the curiosity of my inner child when I first moved to New York and tried to “make it.” I failed a lot at being everyone else, and now I am constantly trying to connect to that raw creative spirit I was born with. I am in a constant state of digging, that feels archeological — and building, that feels pioneering. In the middle of the past and future, aka NOW, I am learning to embrace the good and the bad of my very conservative hometown and use all that information to dig even deeper into my work.

EM: In the interior of the sarcophagus we are looking at we can see code, repetition. Human existence has always been about coding everything.

RK: Coding and symbols. Privilege is a code, and understanding symbols is a key. Who is this taught to? Who is this hidden from? Imagine how meditative it must have been to make this — the creator slips into a flow/trance state and returns to “reality” to see this detailed sarcophagus. What were people tapping into to get into that head space? The code is a set of rules — the script, the credits, and everything else. Repetition is the flow that connects us all. Everything is code, but most is lost in translation.

EM: Again, it goes into that nonlinearity of time and multiple perspectives. At some point you found a fertile zone where you could exist as a human being, as well as an artist, in connection with history.

RK: My interest in myth-making and archeology is that you excavate these ideas to show a connection between all that was, is, and will ever be. Art has been a way for me to stay in motion. Traveling the world, working in different mediums, and exploring different types of creative practice have opened so many doors to understanding. I engage with history to shine a light on what isn’t there. Using traditional forms as conceptual Cliff Notes, I shift through multiple perspectives of existing. I invite the audience to navigate through a creative process that sets up direct confrontations with known knowledge and attempts to make the esoteric and intellectually dense easier to comprehend.

EM: Music has always been a key part of your process of discovery.

RK: Music is universal and has the possibility of bringing people together, unlike any other medium. Even if you don’t understand the language, you can catch the vibe. My exposure to the world was through music. I first experienced “elsewhere” at the opera or on MTV. Music is frequency and sound is creation. I grew up composing, playing instruments, and singing. Channeling new songs and releasing divine vibrations into the universe is the fuel of my creative practice. Having the gift of music is a superpower that allows you to access and share an ancient form of healing and understanding that only exists through song. Music is the answer.

EM: You literally built yourself, your vision of the world, through the emptiness of the place where you grew up.

RK: I resented small-town life a lot growing up, but that is what really allowed me to become a hyper-creative person. I didn’t have a picturesque, inspired, or metropolitan world around me, so I had to imagine it. It was very dangerous for me as a child to go outside and be myself, so I stayed inside and watched movie musicals or great performances and spent a lot of time on the internet at the library. I did not feel like I was a poor Black kid in the inner city of Ohio. I felt I was a soul and a human having this global experience from my house. My parents and my teachers supported the construction of my reality as much as they could, but most of them didn’t understand the magnitude of the calling. I used to view Middletown as half empty, but now I actually see it as half full. The older I get the more I find the fullness within simplicity, and although politically it is backward, and culturally it is not sophisticated… it filled me with all that I have and continues to produce brilliant people.

EM: It has been a way of finding your genius, creating a new representation of the world. Isn’t that what art does?

RK: Art is the best for creating the new. There’s this Elizabeth Gilbert TED Talk where she talks about how people didn’t use to think of themselves as being geniuses but as having a genius. I see myself as a channel for ideas. I’m constantly downloading things and synthesizing different experiences of my life into my art practice, whether it’s the alleyways where I grew up, opening night at the Châtelet, or a barbecue with my family. I hated museums growing up because I didn’t see myself in them. Maybe I didn’t hate them after all, but saw them as my destination. Art connects all of us and keeps us in silent conversations throughout existence; it is the genius spirit in physical form.

EM: Yours is a body technology. How did you move from music to the visual arts? You’ve worked in the fashion industry for at least ten years, meanwhile developing your music and evolving into a visual artist. I don’t like categorizing, but what was this process like?

RK: I went to undergraduate school for dance, so my technology is a body technology, and my deepest knowledge is the knowledge of the body. It was a lifelong process and a lifelong dream. As a gifted music student, I was constantly telling people that I was a visual artist, but nobody would listen to me because it served them more to have me be in the choir and to be a body instead of a mind. I always expressed myself in all mediums, but performing was my priority in the first part of my career. I have always engaged with the world through the visual, starting with my wardrobe. I planned on dropping out of dance school to go to fashion school, and then I booked Fosse. I got injured while doing Wicked and moved back to New York. I started taking nightlife photographs because I only had use of one arm, and I shifted my reality to Downtown NYC. I was already working in fashion/casting, and that led me to work in nightlife and performance curation. I used to feel like paint, but I wanted to be a painter. I started making operas and combined my visual art with music. The overlap of these worlds produced a new vibe and was a great site for colliding concepts. I don’t believe in borders between art disciplines. Music is visual and sound is sculptural. Therefore there is no step but a lean into the unknown of creative technologies. The process began with that curious little kid in Ohio, and it is constantly unfolding.

EM: When did opera come into your art-life process?

RK: I started going to opera at about nine years old. I took a long break and I premiered Black Rage (2016), my first opera, the spring before I went to grad school. I wrote a full-length opera, HIR (2019), during my time at Bard, and I met JP [Javier Peres] and Nick [Koenigsknecht] in LA a few months before I graduated. They invited me to Berlin to make an opera without an audience, which became my first video work (G)Hosting (2019). Opera is life and life is operatic. The more I think about opera and the more I work with and stretch the form, the more I realize that it has always been there. I am just becoming more conscious of it.

EM: It’s hard to reverse the canonical narratives that want to see you as a dancer, or an artist, or a musician, but never as a whole. Yet anyone who saw what you created for the 2023 Performance Space New York Gala (March 2023) would change their mind.

RK: I knew that I was a visual artist my whole life. I haven’t been a professional dancer for fifteen years, and when someone speaks to that period of my creative life, it’s meant to be reductive. I’m no longer reduced by it. My energy is better used to move forward, so any canonical narratives don’t apply to me or any creative person. I know myself, and I see myself fully. I am whole, and I no longer seek any outside source to validate that. I was the creative director of the Performance Space New York Gala on a Saturday and flew to South Korea the next morning, landing Monday for an opening on Thursday. I did a performance there as well. Maybe the order of my life or my ability to move between worlds and mediums confuses some, but they will understand in time. And if they don’t, I’m ok with that too. The gala was a moment when the Nano Ensemble — my ensemble of collaborators — saw the uptown conservatory meet downtown conceptual cool. Anyone who doesn’t see me is intentionally looking away.

EM : I attended one of your live staged operas, Zeferina (2022), within the solo show “Libretto Accidentale” at Peres Project in Milan last December. With voluminous white costumes designed by Claire Sullivan, together with RaShonda Reeves and Kyle Kidd, you explored Black resistance and the roots of Black social liberation movements. And there, as I looked back at your paintings, I understood the connection. You move among media languages as if everything has the same access key.

RK: Boundaries in the art world reinforce a hierarchal system, which ultimately mirrors the problems of the world. I’m an individual who’s occupying different spaces each time I unlock different parts of myself. Liberation is limited by fear of failure. Moving between media languages is a means of resistance. It eludes the box and escapes capture — the fugitive intellectual. Shifting to visual art has made art new for me by opening so many new pathways. The key is creativity, and the secret is that we all possess it. There is not just one key, but an infinite amount, and I hope my exploration of mediums inspires other artists from unlikely places to defy definition and deny being diluted. Creating a space to express myself fully is something very new and at times still scary for me, but this fear is slowly fading as the beauty builds and the backdrops pop.

EM: And is your creativity for sale?

RK:The things I use my creativity to make are, yes, sometimes for sale, but creativity as it is cannot be bought or sold. Art is to be shared, and the artist deserves a good life… but to me some things are far beyond transaction.

EM: It’s like you’re an analog girl in a digital world.

RK: Definitely. I’m down to be in the studio figuring it out, using my hands. Playing acoustic guitar. Sometimes I hit a home run and sometimes I strike out. I didn’t grow up with a computer in my house. My generation was on Tumblr while I was tumbling in Wicked. I’m going to keep stepping up to the intimate space of craft. Analog is the energy and the way that I see the world. Whether it be through painting, dancing, singing, making operas, sculptures, throwing parties, casting, all of it. I create worlds, build experiences, and capture vibes.

Should we keep walking?