Each Renée Green work is an exhibition in itself. Multipart in form, often originally site-specific, Green’s works are precise webs of meaning through histories of migration and displacement, structural violence, cultural appropriation, and the aesthetic forms and languages that were and/or still are attached to them. While these terms might be quickly disregarded — widely used and often generalized in the current moment — it is Green’s work that brings us closer to their actual complexities. They are exhibitions in themselves in how they demand time (several visits are advisable), unfolding content gradually; in how spatial arrangement and display are carriers of meaning; and in how the works are self-contained in their specificity yet connect to other works in their general subject

and methodology.

One of the first works we encounter in “Renée Green: Inevitable Distances,” on view through January 8, 2023, at Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, might be seen as introducing this methodology: “Metonymies” (1984) is a series of vibrant gouaches, each juxtaposing two images that in combination trigger a sequence. Like a psychological test, a dream, or a jump-cut in a film, the disparate images affect certain emotions — here often disturbing ones: the pyramids and a figure holding bricks; Stonehenge and a figure with a large stone that might be on their back and might not; a tree hit by lightning and a figure depicted in the same manner. “Metonymies” is not just about what is being shown, but about how — the codified use of color, the simple style of the drawings, and how the depictions correspond to one another in the grid they’ve been presented in.

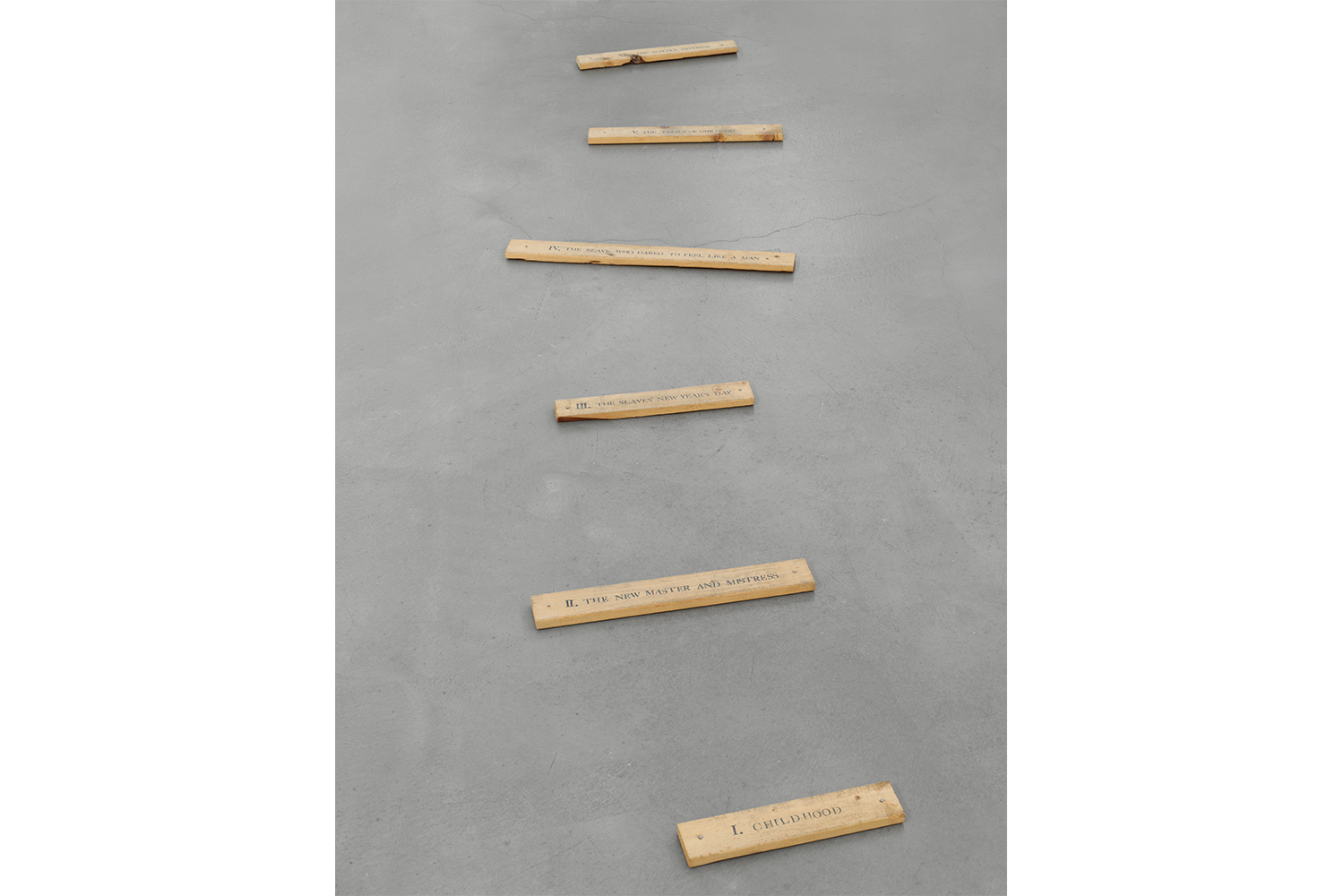

They are also, we read in the wall text, to be read specifically in the social context for which Green made them — Mexico in the 1980s, when US foreign intervention was taking effect. This layering of signs continues throughout the exhibition and guides us through the decolonial process at work in Green’s practice. Her tools are collections of archival material or reproductions thereof, indexes, interviews (most often video), lexica, and much more. The result is a sophisticated semiotics that is simultaneously scientific and fictional. It exposes glorified histories — in museological display, say, as in Acknowledge Your Sources (1989) — and makes space for unwritten histories — listing the names of African languages spoken by enslaved people abducted to French colonies in the Americas as one of the three keys or “clés” in the work Mise-en-scène (1991), a work Green made during a stay near Nantes, where she traced the location’s involvement in triangular slave trade. In elegant boxes and on smart plinths marked plainly with “outils” (tools), “ambiance,” and “point A / B / C,” we compile clues to a horrific history then subverted in the work Commemorative Toil (1992–93) next to it. Pastoral motifs on wallpaper are mixed with images of hangings of colonial oppressors.

Produced, in collaboration with Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, by KW Institute for Contemporary Art Berlin and previously held there, “Inevitable Distances” brings together work from the early 1980s to today, and includes public artworks such as Code: Survey (2005/06), video works such as Slow Walking in Lisbon (1992) and Walking in NYL (2016), the early painting Edmond Laforest (1988), and parts of or entire installations such as Import/Export Funk Office (1992). “Inevitable Distances,” as an exhibition, does not aim to be anything other than a careful presentation of these works. In this it is refreshing; each work’s demand for its complexities to have the space to unfold is met, without an additional layering of institutional bravado via ambitious exhibition texts or curatorial configurations.

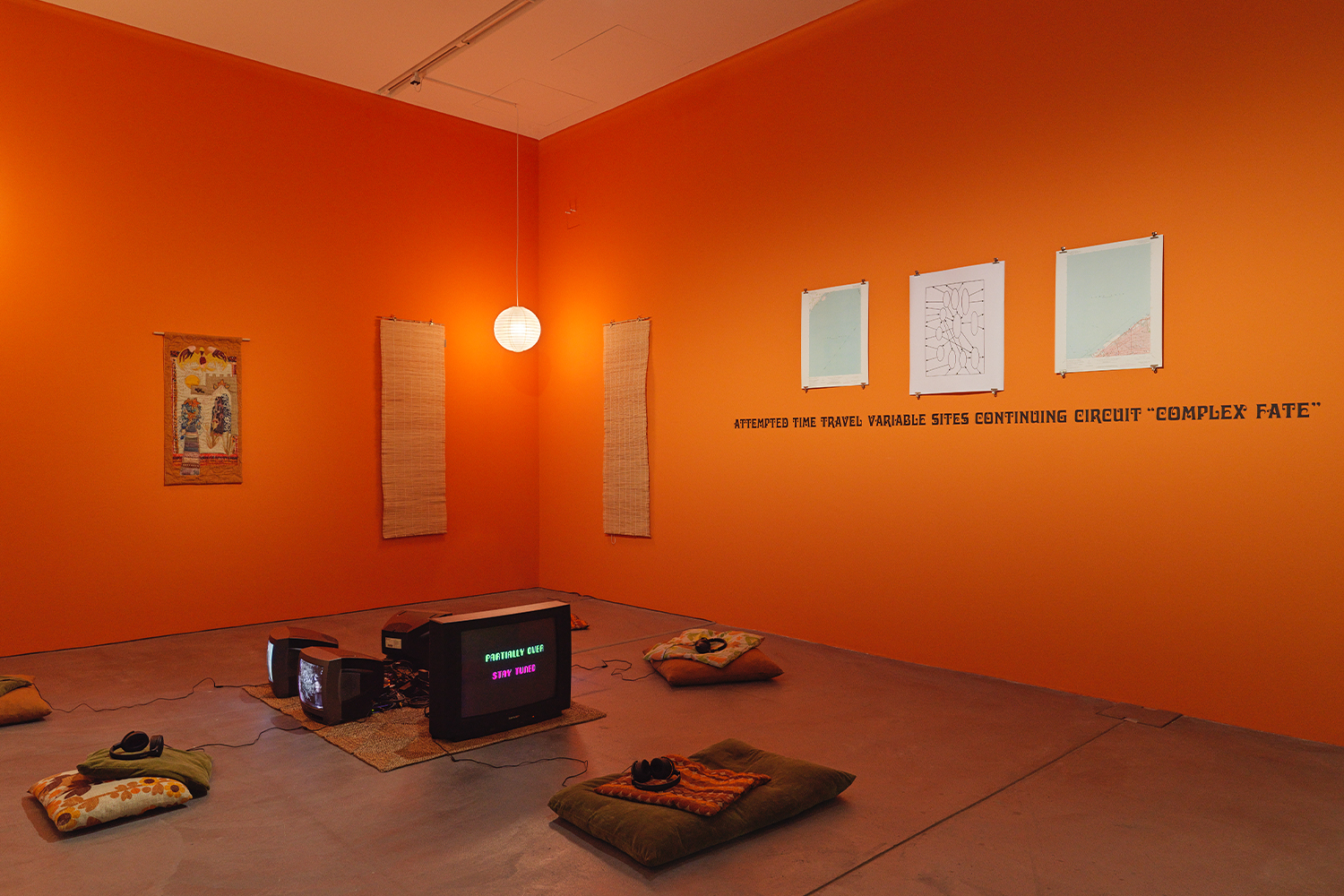

While the term survey comes closest to describing the exhibition (and is used by Migros Museum itself), there is nothing extractive about it. Green’s work, for one thing, makes this impossible, as it occupies the space quite matter-of-factly. Sitting on the cushions in Übertragen / Transfer (1997), I listen to one of the interviewees talk about the 70s: “The political was being buried. You have The Brady Bunch movie out now and everything is hip, cool.” I read in the wall text that the work is the second part of Partially Buried in Three Parts (1996–97), which had as its starting point Robert Smithson’s Partially Buried Woodshed (1970). I learn that shortly after Smithson began the work at Kent State University in Ohio (Green’s home state), four students were killed attending a protest against the US invasion of Cambodia, the date graffitied onto the woodshed. I am astounded by the seeming coincidence of the word repetition and its loaded meaning in the context of the work. These moments, as subtle as they are, happen often, and have a striking effect: the process of unpicking (art)historical canons is almost a side effect — other stories and histories are the focus.