Originally published in Flash Art no. 162 January/February 1992.

The farsightedness with which Weil analyzes the then-nascent 1990s is indicative of the brutal changes that the art world would undergo in terms of how it related to time, to the media, and to the creative process. Examining the ways in which the 1980s reacted to the previous decade and the hangovers from that time, the author carries out a lucid and detailed examination of the art system since the end of the Cold War, drawing conclusions about the artistic production to come. This is particularly relevant to the present day, as indicated by the evident return of certain topos of the 1990s. As Aria Dean suggests in a recent conversation with Hal Foster,1 it seems that we are experiencing the aftereffects of the “return of the ’90s” such that, while on the one hand there has been an evolution and a greater understanding of the “real,” on the other we are still debating the same themes, as if we are literally trapped in the decade that shaped, perhaps more than any other, the society of images.

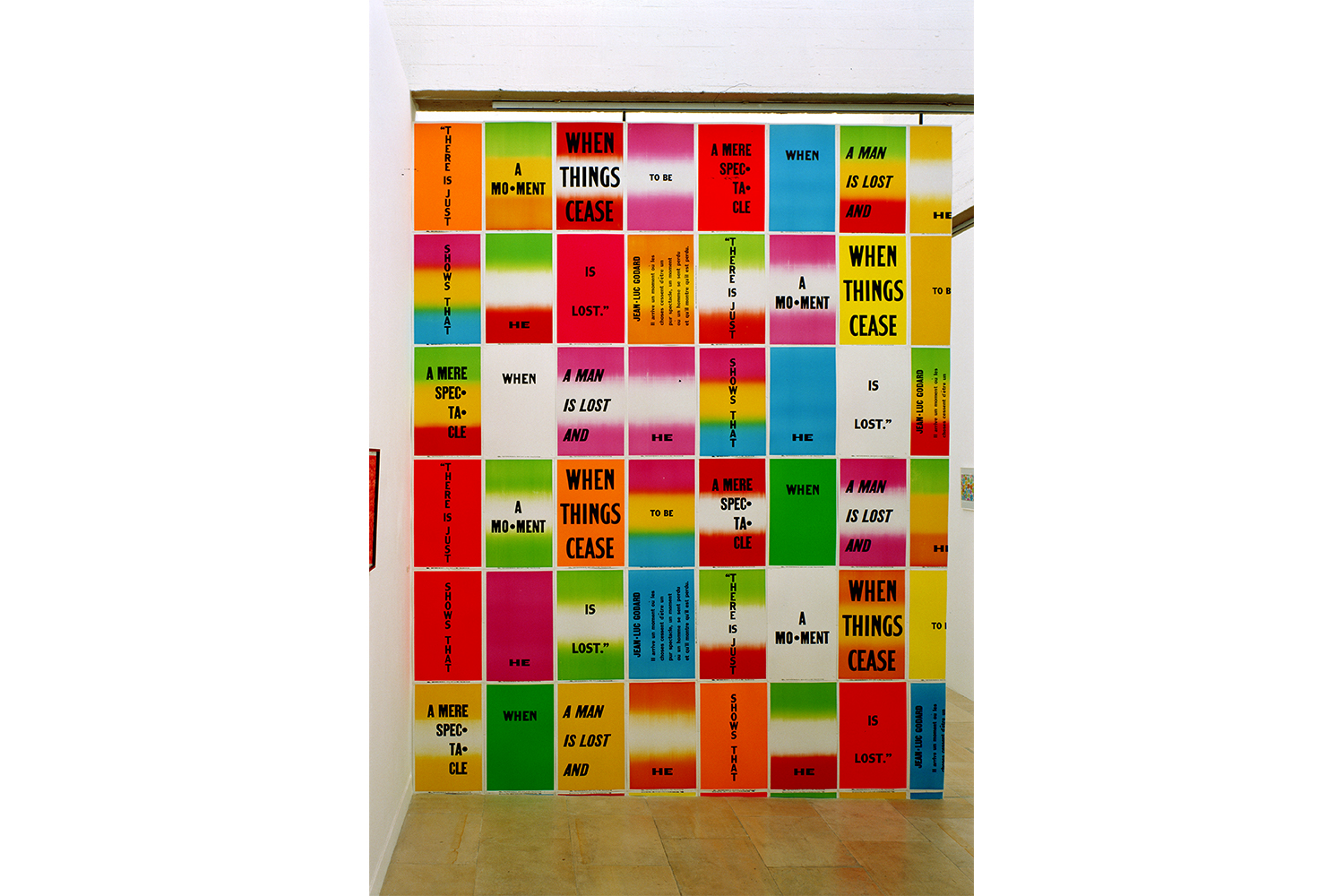

The beginning of the 1990s saw the recurrence of installations as a favored means of communication among a new generation of artists. Although this kind of process recalls the seventies, there are important differences which distinguish these new works from those of a previous decade.

To have a better idea of these differences, it seems interesting to study the context in which these artworks are being made, so as to ground these changes and expose the main issues addressed, and in particular, to acknowledge a specific time dimension—leisure time—in the viewing of art. The 1980s brought and/or confirmed major changes in industrialized countries: the acceleration in the processing and transmission of information generated by global systems of communication and transportation; an economic model based on intensive financial speculation and the development of service industries confirming the end of a system based on production; and the quick access to information as a primary decision-making tool.

This in turn resulted in the reorganization of time frames in everyday life and the way one relates to geographical space.

A constant flow of images released by all kinds of media–advertising, general information, or music videos—has generated a feeling of saturation. The general public responds with a disinterested and blasè attitude, which in turn stimulates the media to be more aggressive: all methods are used to retain people’s attention, particularly the idea of shocking the audience to generate a reaction—whether positive or negative.

The nineties reveal the excess resulting from such a model and consequently its limits: the eighties appear today to be more like a reaction against major structural changes which emerged towards the mid-seventies.

Moreover, issues of social unease in capitalistic cultures, a growing awareness of environmental problems, and a strong economic recession seriously challenge the state of semi- consciousness and super-consumerism that characterized the past decade.

Concomitantly, the fall of communism raises the issue of an alternative to capitalistic order and questions a world in which two mega-countries rule the planet. The development of an intermediate model based on enlightened pragmatism—such as the European social democratic model—asserts the end of all belief in a monolithic political structure.

People seem more concerned by issues that affect their daily life in a more direct way, such as ecology, ethics towards minorities, and/or human rights in general.

Our late twentieth century is therefore left with no particular form of belief with which to generate a new social order; it possesses only an acute consciousness of obvious structural problems. Even science, which we believed would improve our living conditions, is now destabilized by a strong questioning of its thinking patterns. The Platonic belief in a pre-established order created by some subnatural power conditioned science to search for the hidden rules governing nature; chaos theory questions that notion of order and challenges the idea of scientific progress. The illusion of having control over nature through a logical understanding of its mechanisms cannot survive.

This scientific approach also suggests the necessity of establishing strong links between the various forms of research and their own linguistic structures, therefore pointing out a limit to specialization and challenging our whole conception of knowledge.

All these destabilizing elements have contributed to the growing attention paid to art as an important spiritual field in our postindustrial social system and the sole space of iconophilia. The general public’s recent and overwhelming interest in art has generated record attendance at museums, thus profoundly modifying museum structure and mode of operation. Museums, as new spaces worship, have become the natural place for the Sunday stroll, generating such popular events as “blockbuster” exhibitions sponsored by corporations in search of the perfect public relations tool. Museums are redesigned to fit the requirements of this new function; efforts in presentation, didactics, and monumentality are among the clues of this evolution.

Is art the manifestation of the sacred—the respect for our past as the only reliable source of reassurance—or the ultimate form of consumption? Art structures grow everywhere with business goals and attitudes, such as franchising—the Whitney, the Guggenheim—and merchandizing (ie. museum stores selling the perfect souvenir).

Artists in the eighties chose to address all those issues somewhat cynically, either producing perfect consumer icons, and/or openly criticizing the structure of art. Their production dealt with such issues as fetishism, collecting mania, and presentation; grounding art in an economic activity led them to investigate linguistic structures of other dominant image producers, such as advertising. This realization: the result is a much closer relationship between artist and audience.

Artists in the nineties emphasize the shift of the viewer’s mode of interaction with the artwork, positing their research as another form of communication which coexists with all other media.

In relation to another kind of reality, defined by the growing importance of technology in our familiar surroundings and the way it redefines that notion, installations tend to reaffirm the idea of concrete understanding and the importance of the bodily experience in the appropriation of knowledge. This reveals a concern for a closer relationship with the public.

Emphasizing the specific time frame of the art viewing experience renders the artist as an information “editor” aimed at generating a new approach to our environment, therefore enabling the visual arts to assume the position traditional forms of thinking can no longer fulfill.