When I think back on 2018 there is always something that feels misaligned — a disconnect between myself and the present. That year of my life was peculiar in several respects; the sense of stability or solidity upon which I usually depended faltered on several fronts. This may sound like an awkward attempt at autobiographical speculation as I attempt to tackle a monographic text on an artist (it might be a good way to evade the task!), but that misalignment, which returns punctually whenever I revisit certain artistic productions I was interested in at the time, has meaning. The last few years — pandemic rhetoric aside — have been what I would call rather “intense” in the visual arts, which have increasingly turned to time-based productions, in an attempt perhaps to render the unspeakable in a more complex form.

Obsessive depictions of the nonhuman — to name the most pervasive example — or alternative ecosystems or identities, within what has been cleverly called the era of the “Extreme Self,”1 I feel are leading to a general misalignment — to a difficulty in reading many artworks with anything like lucidity. Lately, this is precisely why I look at so many productions with suspicion, which I then impose upon the works that I observe but also on my own ability to understand and see. It is always a game of contingency; after all, what has changed since Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (1913) or Brancusi’s Princess X (1920)? Everything and nothing. Today the game still hinges on identity: not on the art itself — that was a psychopathology of the past century, when art was still an ontological priority — but on the identity of the artist/person in relation to the world, nature, society, politics, digital self-representation, and sexuality. (I) ask again: What has changed?

The misalignment I speak of is experienced temporally, spatially, but mostly intimately. Returning to an obsession with identity, I am reminded of one of the most interesting things I have read in the past few days, a brilliant report on the 59th Venice Biennale as part of Dean Kissick’s monthly column “The Downward Spiral.”2 Kissick cites Sean Tatol’s editorial in The Manhattan Art Review, in which Tatol states that art today aims to represent affective phenomena through the artist’s biography and identity while dissociating from the intrinsic meaning of the work.3 This disconnect is due to a cogency that we have wanted to abandon in favor of a need to tap into more dimensions unrelated to art itself, in order to (perhaps) return to understanding again.

Intimate Misalignment

The feeling of disorientation that has accompanied me these past few years I strongly associate with the first time I saw a solo exhibition by Raphaela Vogel, at Kunsthalle Basel in 2018. “Ultranackt,” as the exhibition was titled, was

in some ways revelatory of the germ that had already been in the air for quite some time, and which exploded before my eyes on that occasion. The thing that struck me most about Vogel was her extraordinary ability to occupy space and combine such personal and intimate registers — in which she obsessively appears as herself, “self-portrayed” in each video — within a distinctly formal matrix. This is the mental state of disconnect I discover every time I watch a Vogel video — including one of the earliest, Prokon (2014).

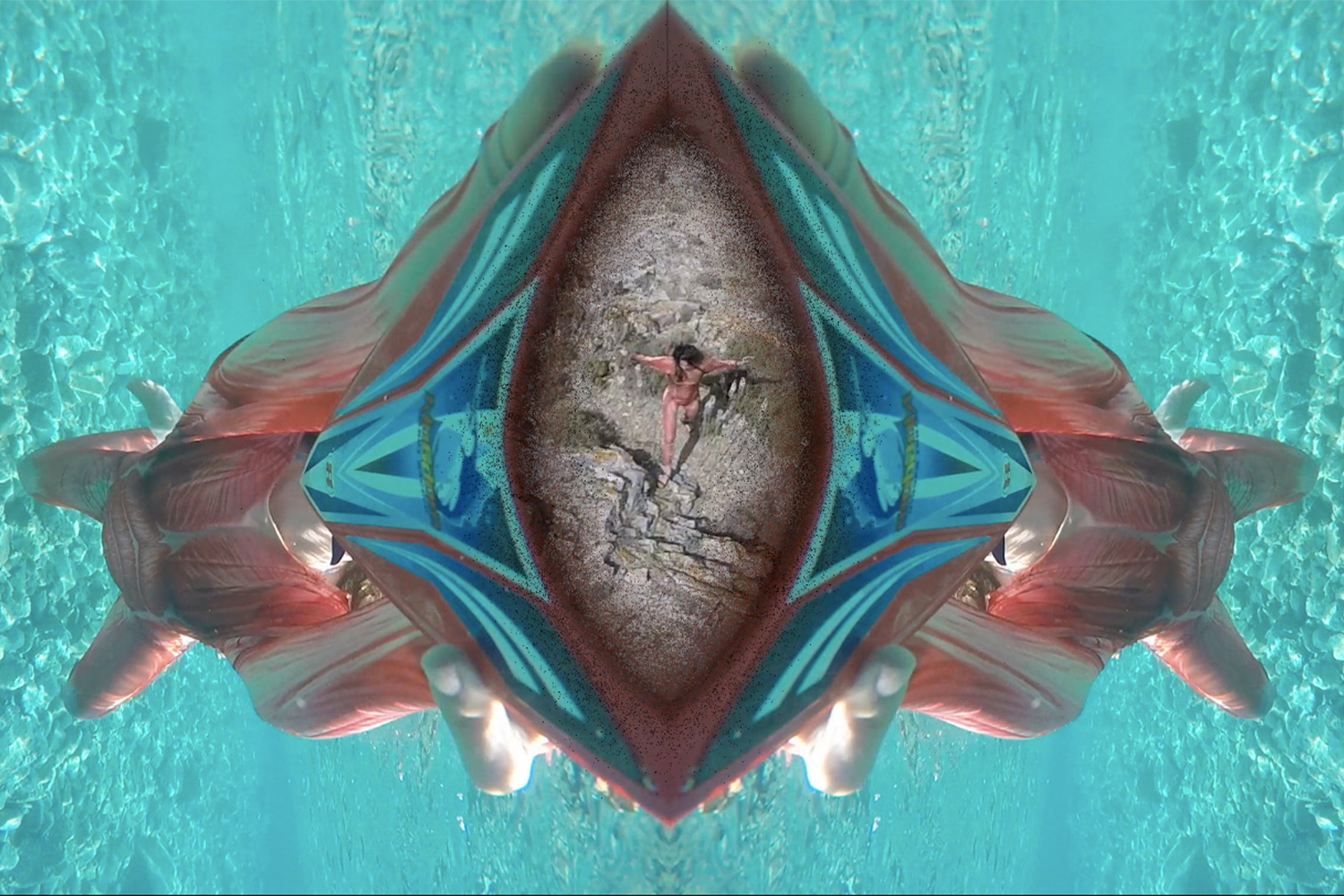

The supposed narrative that Vogel is always about to create in her videos is like a trompe l’oeil in the pictorial tradition — an illusion, one that never really begins or ends. The illusion incorporates within it found footage mixed with banal depictions of domestic life, which blend into apocalyptic or picturesque landscapes that are accompanied by dirges, ballads, or techno-metal mixes peculiar to German culture — all of which are seemingly celebrated on the one hand while also being cleverly demystified with an irony that is anything but subtle. The video in the Basel exhibition, Isolator (2016), stages the myth of Marsyas, which functions as a pretext for problematizing megalomania, the arrogance of the outsized ego — that of a satyr who challenges the God of music in the case of the myth, and more generally an infinitesimal being who would like to defy time and space but is doomed to be confined by his own limitations. But metaphor is a tool Vogel applies to the structural qualities of her video productions: in Isolator, the excessive framing of the landscape, the loud sounds, the eerie drone-eyes that stare at you, fracturing the intimate moments in which Vogel softly sings her ditties: all generate continuous dissonance. Her layered videos, and the way she thinks about physical media, making the videos coexist with the sculptures in hybrid architectural spaces, is self- conscious to the point that neither the viewer nor the artist can separate the art from the questions of identity that are brought to the surface. Her presence — in Son of a witch (2018) as well as in other videos — generates a perpetual state of confusion. She uses a selfie stick to rotate the camera directly above her head, or uses wide- angle shots to create abrupt shifts in perspective, in which elements of the landscape unexpectedly become active characters in the narrative.

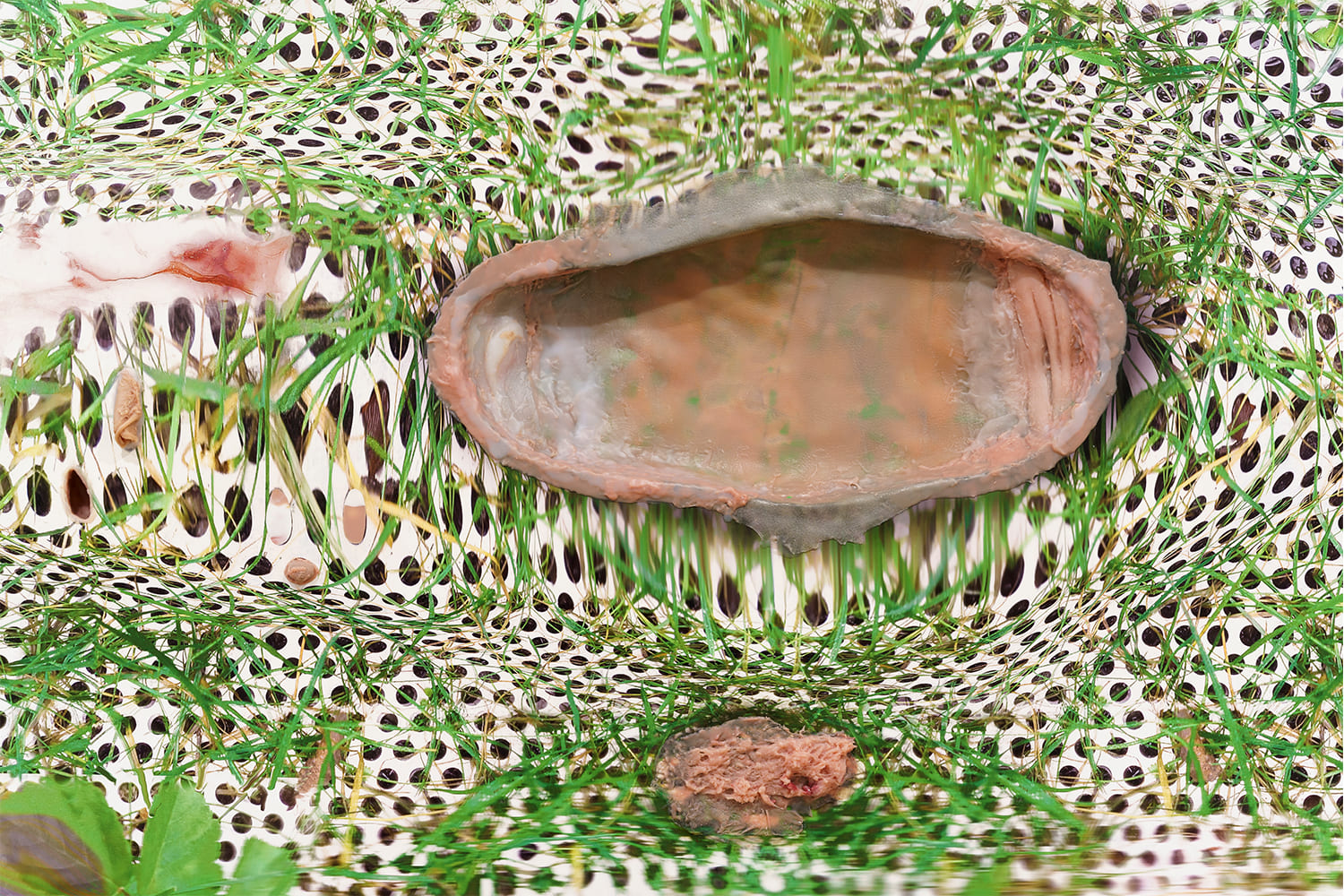

In some ways, Vogel’s work explores the male gaze of technology through the use of her own body, in concert with and in an antithetical relationship with that of the drone, which is ubiquitous in her practice — as an image, or as architecture in space. The moments when Vogel seems to force her body into a sexualized representation make clear the failure of certain stereotypes that still reside in language and iconography. The materials involved in Vogel’s multimedia installations seem to be in a constant state of metamorphosis; each element finds its place, its precarious balance in a system in which it manages to coexist in one way or another.

Sculpture as Simulacra

In this complex universe, sculpture has an important weight; it is simulacra of cultural and systemic legacies, an “inflated sign” in Vogel’s words. When I saw her leather sculptures I thought of the eight latex, fiberglass, and cheesecloth elements in Eva Hesse’s Contingent (1969). In Hal Foster’s reading of it, Contingent refers not so much to the body as to a series of drives, desires, and fantasies peculiar to Hesse’s autobiography — her mother’s suicide, her illness, and her existence as a woman carrying a legacy of pain. In some ways this same approach can be discerned in Vogel’s sculptures, in her use of the skins of elk, cattle, goats, lions — leather fragments as “an atavistic form of an image,”4 as the artist defines them, as well as evoking the male anatomy in a completely dysfunctional way. Symbols of masculine power are reiterated in Vogel’s sculptural installations in the form of drones, lions, and horses in works such as Kopfschuss (Shot to the Head) (2018). These elements are ironically interrogated in a tense relationship with the artist’s self that lives within the screens.

On display within the main exhibition of the 59th Venice Biennale is the installation Können und Müssen (Ability and Necessity, 2022), an oversize anatomical model of flaccid and cancer-ridden male genitalia led by a procession of white giraffes. The sight of these white polyurethane giraffes hints at the whiteness of milk (perhaps a reference to the exhibition’s title, “The Milk of Dreams”), but a more macabre interpretation would suggest that these are sperm that a diseased penis cannot control. The volume of these carcasses, so light and ethereal on the one hand but so terrifying in visage, defines a void, a body that is always abject, that exists precariously, questioning the concept of power by internalizing it.

Many of the Vogel’s sculptures are casts of carcasses, including the first ones I saw in Basel, titled Uris (2018), spread out in a thread along one of the narrowest connecting walls between the rooms of the Kunsthalle. They were in fact casts from a urinal, but their formal presence was so compelling and stable on the floor that they looked like undefined entities — asexual bipeds advancing toward the viewer. These forms expand from video and sculpture into veritable architectures that function as circuits within which Vogel’s various iterations of power coexist in complementary ways. They are truly dysfunctional ecosystems.

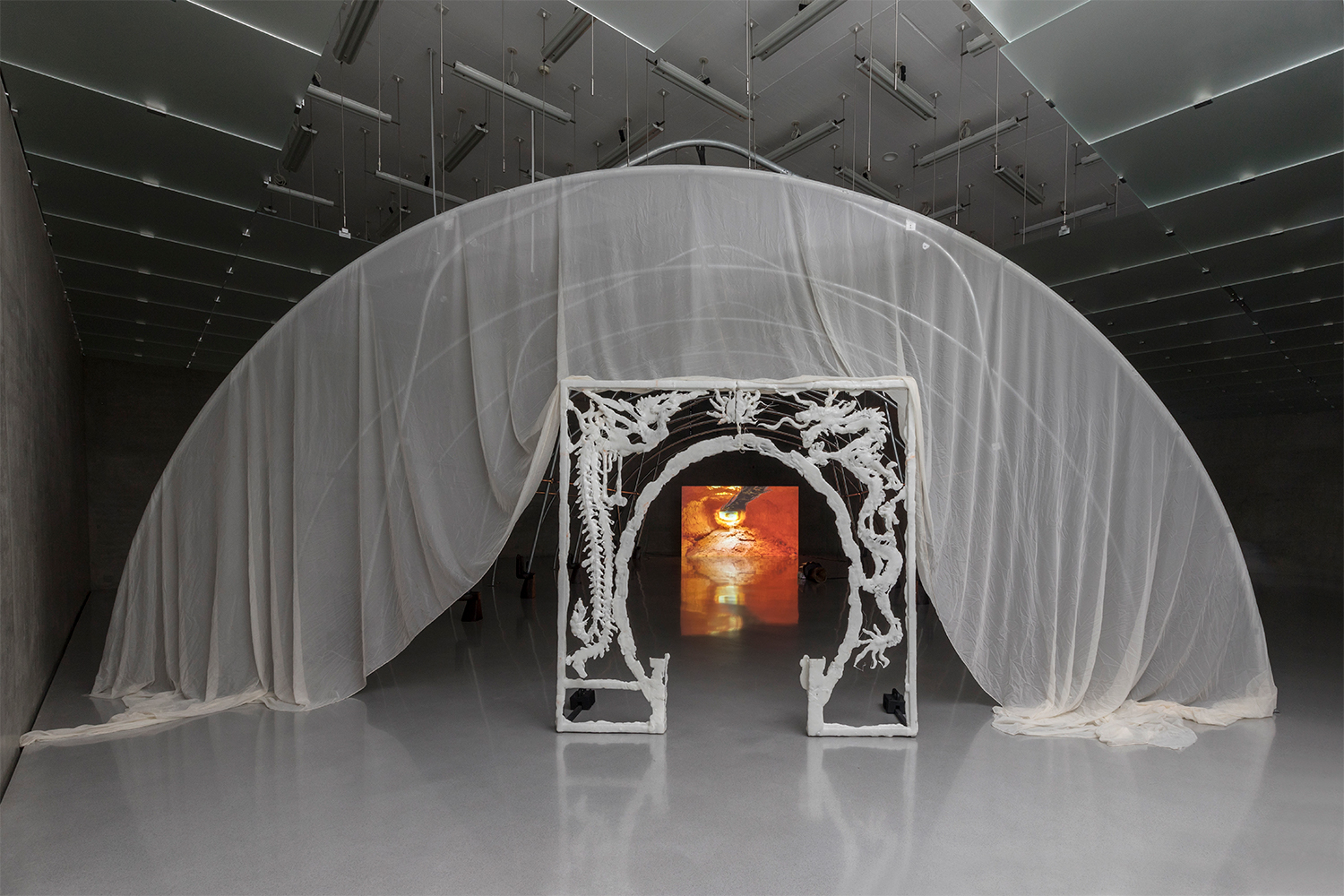

In her latest exhibition at Galerie Gregor Staiger in Zurich, “Vor den Toren der Sprache,” Vogel presents two installations, a new series of sculptures, and a video. Once again an array of heterogeneous elements articulate a layered vision that questions the artist’s existence as a mother within the work while attempting to deconstruct the function of language, and thus the work itself. The space of Zollikerstrasse is divided by a structure reminiscent of roller coaster tracks in an amusement park. These tubular steel units seem to demarcate the passage from one state to another; in fact, they emit recorded sounds of infants in the stage prior to language. The title of the exhibition, which means “at the gates of language,” marks an important moment in Vogel’s research: here language as a tool for accessing knowledge — at such a unique stage in a human being’s life, when the ability to differentiate phonemes is high — is translated into a physical dimension that expands from the screen.

A series of white polyurethane sculptures, this time casts of radiators, look like hybrid animals that cannot be classified. Arranged around the steel structure they seem to protect it in a static monumentality — another abject object crystallized and in its own way aestheticized.