Abstract painting has a long history in Sweden. Indeed, modern abstraction may have been first manifested in the painting of the spiritually inclined Hilma af Klint, whose vibrant divergences from traditional forms of representation precede Kandinsky’s shift away from representation by four years. Two inheritors of af Klint’s approach are exhibited together at Malmö Konsthall: the modernist innovator Inger Ekdahl and her younger interlocutor, Ragna Bley. The exhibition offers an engrossing artistic dialogue as Ekdahl and Bley approach abstraction with sharply divergent voices.

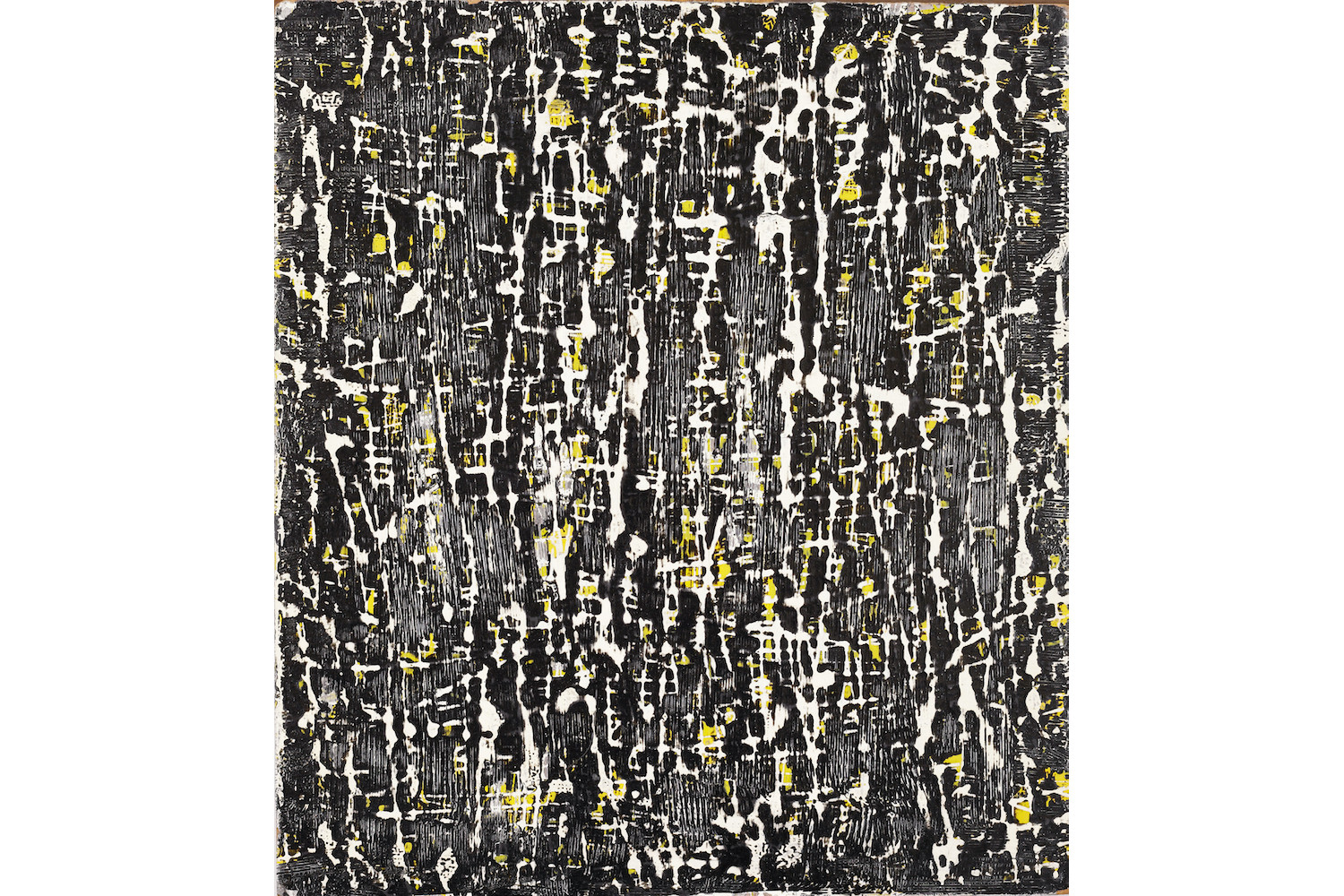

Bley’s large paintings appear in procession in the Konsthall’s main space. Under the series title “Truckers,” large-scale enamel-and-digital-print-on-PVC works are stationed one after another across the spacious main hall, with two prints in each step of the sequence positioned back to back. Bley’s works have an appealing looseness, by turns biomorphic and hallucinatory. With their one-word titles — e.g. Lie, Palm, Fast, Be, Ask — I found myself drawing parallels with the otherworldly emotional states evoked by the music of 1990s shoegaze icons My Bloody Valentine. Bley clearly has a taste for the unsettled; also included in the exhibition are five mixed-media canvases displayed in the Konsthall’s courtyard, which were taking a battering in the gales of wind and rain soaking Malmö on the day of my visit.

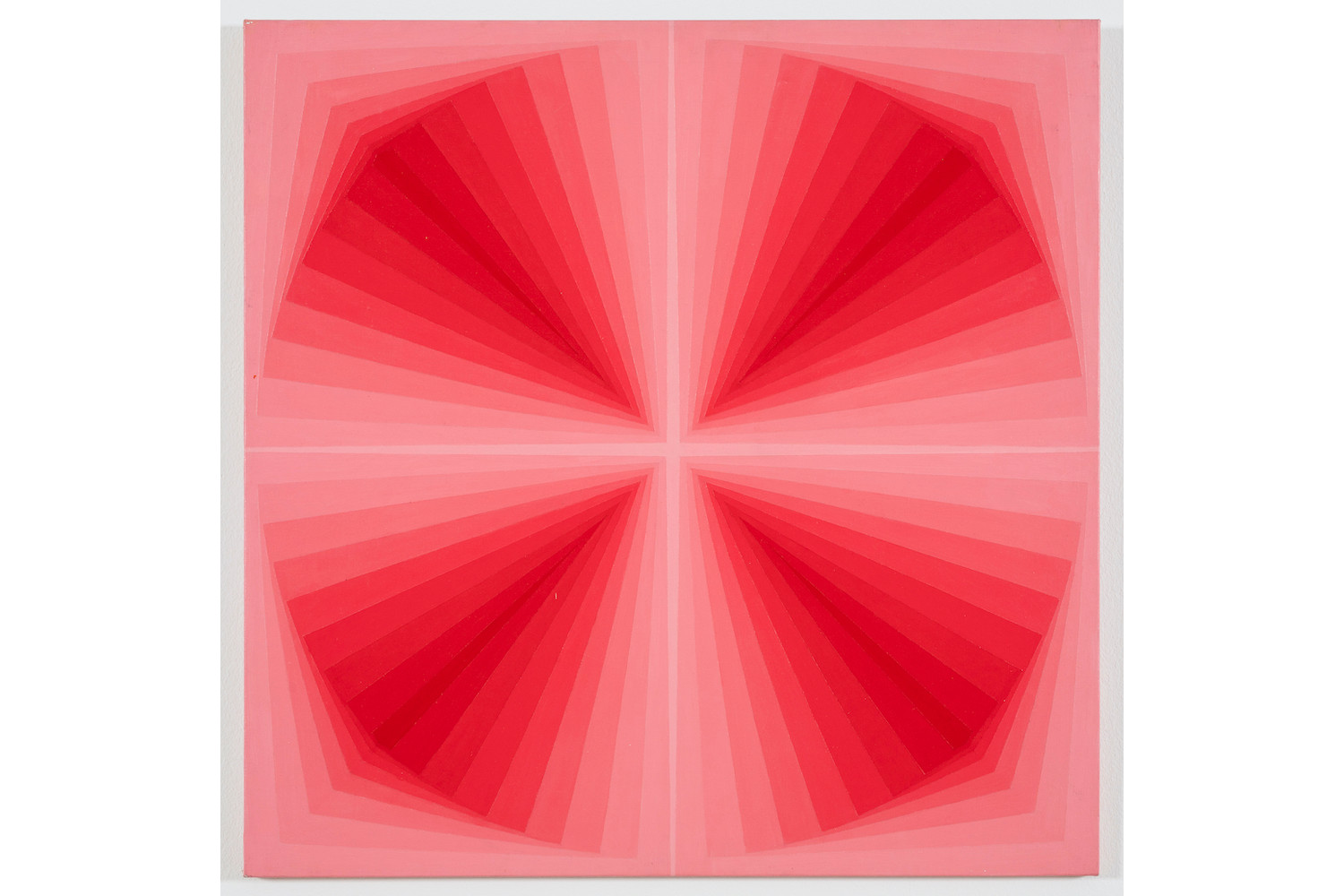

Bley’s abstraction is perhaps earthier than Ekdahl’s. Displayed in an enclosed corridor of their own, Ekdahl’s works, spanning nearly three decades of activity, evince an endless fascination with the dynamics of color and spatiality. Ekdahl’s variation of abstraction could be said to have a spiritual dimension, but it is an almost platonic spirituality, a discourse of forms that often — but not always — harmonize. The canvases and works on paper in Ekdahl’s section of the exhibition are considerably smaller in scale than Bley’s works, but they gesture toward the infinite. To move between the sections of the exhibition is to consider the lineage to which these images belong, moving from the hermetic spaces in which, one may recall, af Klint kept her work hidden, to Ekdahl’s brilliant non-spaces, to Bley’s rain-drenched canvases; abstraction, too, can be seen to have undertaken a journey, from the mind to the world and back — and back again.