Andrea Bellini: Dear Federico, let’s start from the very end, that is to say, from the end of the world. The series of podcasts I commissioned you to make for the digital platform of the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève are about preparing oneself to experience the end of the world. The idea of a cultural apocalypse is quite central to your philosophy. Can you tell me briefly: What’s the end of the world?

Federico Campagna: My starting point is that a “world,” a cosmos, is not a “natural” thing, but it is a “likely story” about reality. Humans, like all creatures, are endowed with limited cognitive abilities. To live, we have to simplify the avalanche of raw perceptions that invest us at any moment and to transform it into the simple and meaningful narration of a “world,” which we can recognize and navigate.

When we say “world,” we don’t indicate an autonomous reality. The world is an artificial construct of the imagination, and we can engage with our continuous activity of worldbuilding in many alternative ways.

Different living species make “world” differently, and, throughout history, various human groups have produced different stories about the world, thus living in authentically different worlds. After a while, each cosmological narration exhausts its narrative cycle and it comes to an end: its future runs out and an apocalypse befalls it. Our planet has witnessed many historical apocalypses. But also each of us, as an individual, has gone through several “ends of the world” in the course of their own life. Think of the passage between childhood and adulthood: the metaphysical structure of the world is very different in the case of a child and in that of an adult. The passage between a person’s ages amounts to the apocalypse of one story of the world (where, for example, the darkness inside a wardrobe is endowed with an ontological status and an agency of its own) and the creation of another cosmos, in which reality itself is structured and populated differently.

A.B.: We are living through a very complex time in human history, with the development of new technologies that will soon be beyond our control, and momentous social transformations, including a pandemic that has been challenging the world economy and the mental health of each of us. Do you think we are living the end of the world?

F.C.: It seems to me that the likely story about the world which is currently hegemonic over much of the planet — what we could call the ideology of Westernized modernity — is now reaching its narrative climax.

The increasing rigidity of identities, the automation of most decision-making processes, the acceleration of all forms of extraction, and the limitless expansion of armaments count as the accomplishments of a cosmology where passports are more real than people, financial values are more legitimate than mystical illuminations, and the permanent incarceration of a large part of the planet’s living creatures counts as normality.

The problem is that this intensification is also setting the conditions for its self-containment and, ultimately, for the disintegration of the contemporary world as we know it. Year by year, the risk of a planetary environmental disaster intensifies and, in the absence of organisms of international reconciliation, also grows the risk of a global conflict fought with highly destructive weapons. Any major disruption of this kind will be able to interrupt the networks of production and supply that currently sustain the techno-body of this civilization. Simultaneously with the fall of its infrastructures, Westernized modernity will be deprived of the broadcasting systems which instill its “common sense” in the minds and lives of its subjects.

The world of Westernized modernity will lose both its social body and its cosmological narrators. For a while, the silence of a “dark age” will spread over the territories that used to belong to this civilization. Then, new stories of the world will emerge from the ashes of our dead world, as they have always emerged after the end of a civilization.

A.B.: Indeed, the Italian ethnographer Ernesto de Martino, author of the extraordinary book La fine del mondo, contributo all’analisi delle apocalisse culturali [The End of the World: A Contribution to the Analysis of Cultural Apocalypses], published for the first time in Italy in 1975, argued that there has always been an end of the world. He gave the example of the Aztec and Mayan civilizations, wiped out by European colonizers. For those peoples, the arrival of the white “civilizers” represented exactly the end of the world, the end of their world. I would like to add that de Martino already in the early ’60s was one of the few intellectuals who adopted a decentralized perspective with respect to Western culture, to pose the question of the crisis of colonialist societies. As a matter of fact, what we have said so far, dear Federico, can be found entirely in the frame of the reflections developed by de Martino in this book, which has been fundamental for me and I imagine for you too. I have the feeling that your latest book, Prophetic Culture (2021, Bloomsbury), has the ambition to present a sort of development of de Martino’s thoughts. It seems to me that ultimately your book raises the question of how we can speak to the people who will come after the end of the world. Is it true?

F.C.: You’re absolutely right about de Martino’s importance — it’s a scandal how little published he still is in the Anglophone world! His book Il Mondo Magico profoundly influenced my ideas on the fragility of reality, which I exposed in my previous book Technic and Magic (2018). In my new book, Prophetic Culture, I focus on the problem of our cultural responsibility towards posterity.

We are rightly aware of our environmental responsibility towards future generations; but do we ever think about what our cultural legacy is going to be?

The totality of our digital records will vanish as soon as the technological infrastructures built by Westernized modern civilization collapse. Most buildings, built cheaply under capitalism, will rapidly disintegrate into shapeless mounds of concrete and unwalkable fields of glass and steel. Paper will not last much longer, either.

Are we satisfied with our cultural legacy being reduced to the devastation which we have inflicted on the natural environment?

But the problem is bigger than that. The question, I believe, should be: What can we offer to posterity that will help them build a new world after the demise of this present one? I doubt that our contemporary culture would be able to offer much in this regard; and, in any case, its language is too self-referential to be understandable by people who will live in an altogether different “world.” But we are still in time to change this state of things: we can consciously lie about our cosmology, thus inventing a better past for ourselves and for our posterity, and we can look for alternative ways to convey our fertile lie across the threshold of the next apocalypse. In this book, I look at the very long tradition of “prophetic culture” to draw the general traits of those cultural legacies from past civilizations that have been able not only to cross world-boundaries, but also to help the creation of new worlds. Am I right to guess that this is also an interest of yours? I’m thinking about your recent exhibition “Writing by Drawing,” and about your work on the late world-destroyer, world-builder, and interworld-traveler Chiara Fumai, both at the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève.

A.B.: This is true. “Writing by Drawing: When Language Seeks Its Other,” was an exhibition about the shadow side of writing: writing that has abandoned its communicative function and moved into the realm of the illegible and unspeakable. It was also an exhibition about what de Martino used to call the “individual apocalypses,” the end of the world in its psychopathological dimension. This type of subjective apocalypse is certainly the fruit of modernity, of a difficulty of individual adaptation to the “new tale” of the modern world. Chiara Fumai has something to do with this: her punk feminism anticipated the current atmosphere; she poetically and politically wished for the end of the patriarchal world, our current world. In the meantime her own world ended up collapsing, but we might think that she came to announce the world to come. In your upcoming book you talk about the figure of the prophet as a stutterer; you affirm that a prophet never belongs entirely to their own world and is certainly never fully contemporary with their own historical world. In some ways a prophet is never entirely themselves either: they perceive themselves as an entity that exceeds the contours of a defined identity, a sense of belonging, an individual self. I’m still thinking about Chiara Fumai here. So who is the prophet? Can they be the artist?

F.C.: Anyone can speak or make art prophetically, as long as they occupy the place of the prophet. The term “prophet” does not indicate a limited group of people, and it doesn’t require (actually, it often precludes) original production. For example, Mohammed was not the author of the Quran, which was revealed to him by the archangel Gabriel; Homer did not invent the Iliad, but prayed the Muse to sing it to him; it was not Moses who wrote the commandments, but Yahweh; it was not Parmenides, but the Goddess, who uttered the logos of the “path of the day”; the Christian congregation did not speak but was “spoken” during the Pentecost; and so on… A prophet is not an author, but it is a cosmological place: it is a point of perspective towards the avalanche of perceptions that invest us, and it is a method of attuning one’s own way of seeing and hearing.

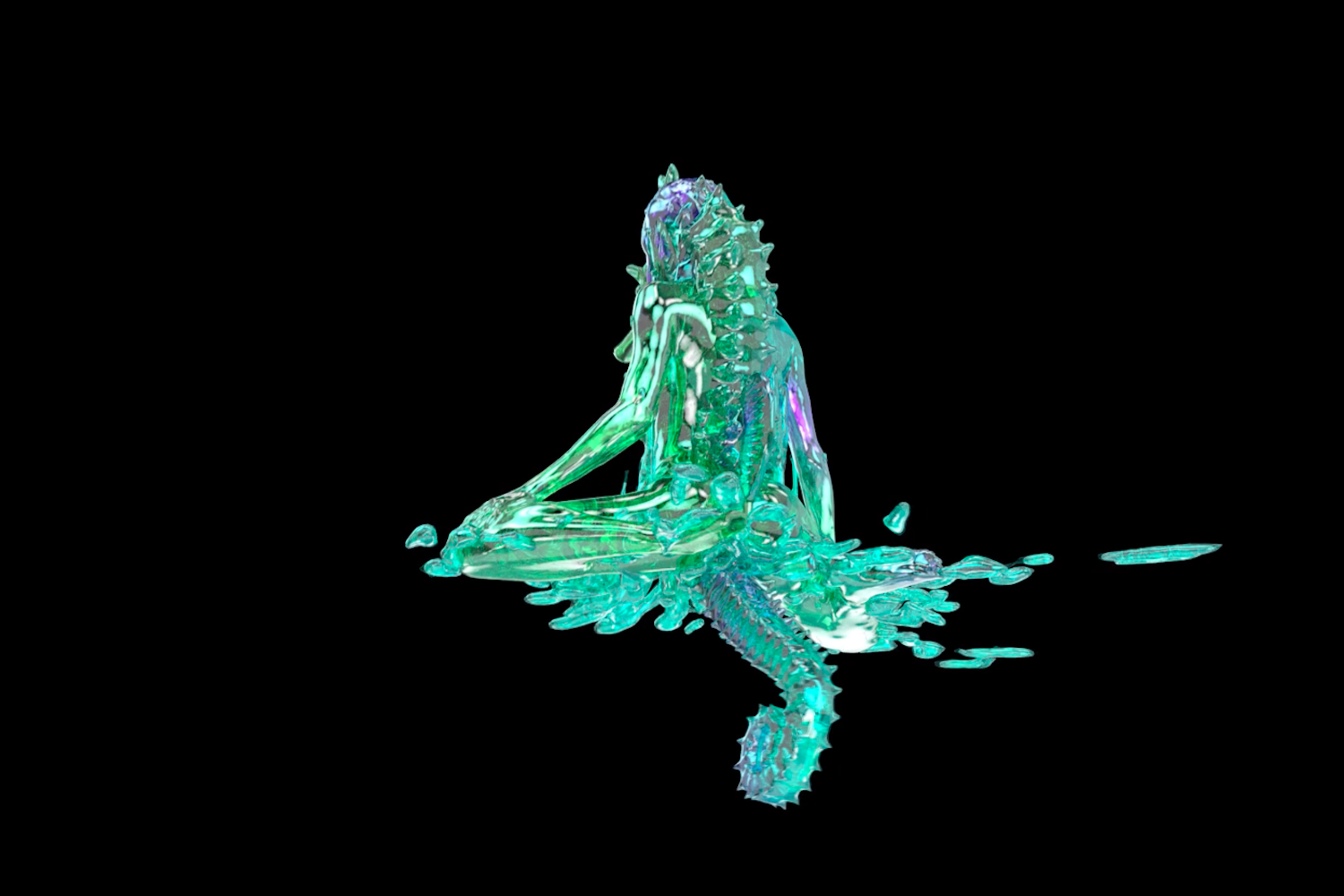

From the prophetic viewpoint, reality appears very differently from the mono-dimensional metaphysics to which we are now habituated. Prophetic reality is a multidimensional realm, where only a portion of what composes us and surrounds us falls within the field of the nameable and the visible, while the greater part remains beyond the grasp of any form of linguistic capture, in eternal ineffability.

From the point of observation of the prophet, the “world” looks like an island of language, traversed and surrounded by the waters of many other dimensions, further and further removed from it. Within each speck of existence, there is a lot more going on that we will be ever able to address not only through the means of language and reason, but also through our emotions and our imagination.

Like any existent, also every awareness in the world — whether in the form of a human consciousness or in any other form — is always in excess of itself, and a great part of it lies beyond its own comprehension.

This is a vision of eternity within time, of what is symbolized in Judaism by the day of rest of the Sabbath, the great “cathedral in time” where the presence of the ineffable is recognized in its mystery. Having witnessed this cosmology, however briefly, some people might wish to maintain it as the “likely story” upon which they run their daily life, and thus to “speak out” about it, through their work, “in front” of other people (pro + phēnai, the etymology of prophecy). If they will wish to do so, however, they will have to reinvent their relationship with language. To speak prophetically, and to express the paradoxical “coincidence of opposites” at the heart of existence, they will have to tear language apart and to reassemble it in grotesque compositions. Their cultural production might not be cool or pretty, but its story will remain imperishable to the apocalypses of history, and it will be able to speak to all worlds, because to all of them belongs the mystery. Such a form of prophetic culture might also be able to advise those who will come after us on how to include this mystery within their own cosmologies, and how to recognize its presence within every existent.

A.B.: A prophet is not an author but a cosmological place. I’m sure Chiara Fumai would have been happy with that definition of her own identity, or lack of identity, as a performer.