Crisis engulfs Emily Segal. Several years after the Great Recession, Segal is freshly unemployed and has moved out of her former boyfriend’s apartment to embrace an amatory flooding for other women. She also lacks the recognition she craves as a burgeoning artist in New York City, the epicenter of hustle and high-voltage ambition. A talented branding consultant, the protagonist won notoriety for writing provocative trend-forecasting reports with her artist collective that breathed fresh intellectual life into the moribund corporate formula of the “trend report.” Trend forecasting reports, which can carry annual subscription costs that reach into the five-figure range, are traditionally PR gimmicks that claim to predict new consumer behaviors. After splitting the profits five ways between the members of her collective, she’s looking to cash out on her own. Who would blame her?

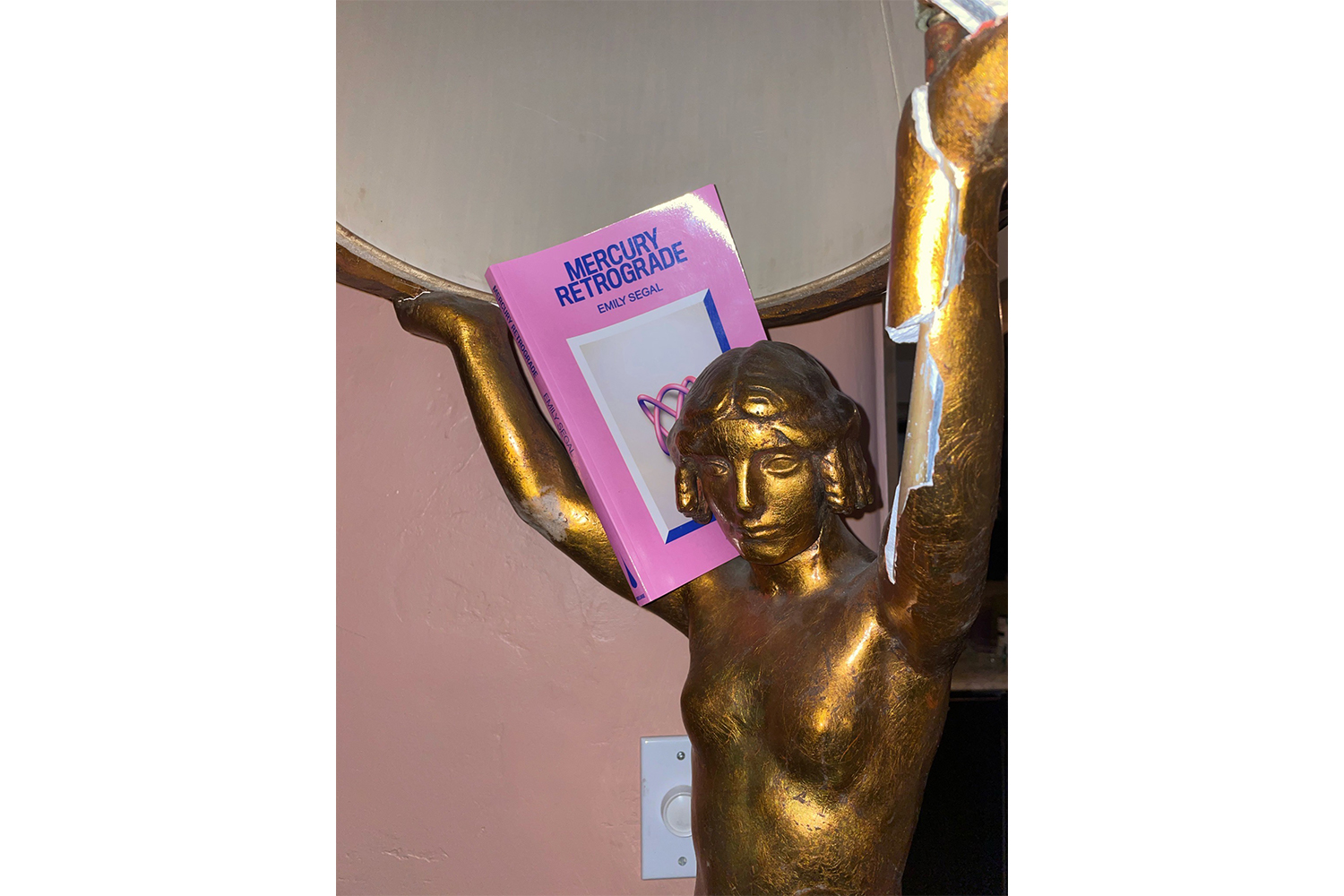

At the beginning of Segal’s first novel, Mercury Retrograde (2020), the unemployed artist is pressed to resolve an irritating combination of loneliness and defeat. Segal’s semi-fictional character is also eager to distance herself from a previous job spent rebranding an evil aerospace tech conglomerate. Low on gas and high on failure, Segal attributes her misfortunes, as well as her disheveled clothing ensemble and frantic eye twitches, to the astrological phenomenon referenced in the book’s title. The phenomenon is also an alibi that allows her to blame her struggles on something celestial rather than on human-made problems. In Segal’s telling, Mercury retrograde is not merely a movement of the stars but a catchall for explaining both society-wide and interpersonal breakdown of communication, “an information economy in constant glitch.”

As further proof of this, Segal received a number of muddy emails from a startup cofounder over the course of a year that culminated in her triple breakup. In the emails, the artist is offered the job of a lifetime: to rebrand Web 2.0’s hottest start-up, eXe, which is infamous for its quirky mission to annotate everything on the internet. What does eXe do exactly? It’s a tool that allows users to leave comments on primary documents. As a product of the big tech bubble of the late 2000s, the business was founded during an era when optimistic people believed access to the internet was the path toward a future of social utopia. eXe, which is pronounced as one syllable, “X,” rather than three syllables like Charli XCX, started as a blog. Unlike other blogs, eXe had a collective editing functionality devised by a group of friends eager to spell out the meaning of rap lyrics to an out-of-touch friend.

The platform grew rapidly in size, spawning a community of anonymous contributors analogous to those of Urban Dictionary and Wikipedia. After achieving a certain scale, eXe was subsequently pitched to investors as the “Talmud of the Internet.” Segal recalls that in its beginning eXe was “the ultimate perversion of the male literary impulse.” The website became an online gathering place for a community of annotators, self-proclaimed linguistic and cultural studies “scholars,” who accumulated “points” by adding annotations to lyrics. The collectively decoded cultural references became a competitive sport, gamifying expertise, for a virtual community devoid of human touch and nostalgic for university days.

Housed along the whimsical Williamsburg waterfront, eXe is led by two attractive men: Seth, a charismatic writer-turned-hypnotist, and Piet, a frenetic Floridian patrician. In the founders’ self-mythology, the online platform is a rhizomatic machine injecting a critical layer on top of the web via socially mediated fact-checking and scholarly debate. eXe worked much like an after-dinner digestif, both numbing the overwhelming accumulation of information from online scrolling while simultaneously stimulating its digestion. For Segal, the startup has more in common with a premium talent agency than anything else, though exactly what the talent has been recruited to do is hazy. Large portions of the seed capital raised from VCs are set aside for hefty salaries, and lavish bonuses are given to employees who recruit artist friends and intellectual peers. Investors seemingly craved a sip of the optimism and idealism, the verve and vigor, of a maturing generation reaching novel freedoms found online.1

From the start, though, eXe never had a clear monetization strategy. As Segal recounts in Mercury Retrograde, the company’s employees, lacking a definitive strategy or a product or service with a clear business model, are terrified the investors’ money will run out. “Around the office, my coworkers were becoming increasingly distressed, and this time I found it less basic. Salaries were getting slashed and unslashed in an afternoon, in dark rooms on the lower levels; tear-stained millennial faces emerged back into the lobby from off-site conversations with The Boys.” The dread is palpable.

Motivated by her dwindling checking account, the artist accepts an interview at eXe. It’s a tedious, day-long affair with several panels of aggressive interviewers challenging Segal on everything from pitching a product sponsorship to Slim Jim to consulting on meticulous details, like username placement, on eXe’s website. The meeting ends with interviewers sharing a video capturing the founders at a conference asking a moderator, “Who cares about our monetization strategy, why are you so obsessed with money?”

Segal’s emphasis on Seth’s “you” is of much significance and distinguishes her novel as a tale deviating from the autofiction roman à clef trend of her peers. Segal interprets the founder’s defensive flair as idiosyncratic behavior rooted in typical, male-dominated startup logic: failure. A startup’s initial monetization strategy has little to do with the value of the product or service being sold and instead relies on investor funding and loans. If a startup emphasizes short-term profits, it will, of course, lose the opportunity to establish a long-term strategy for making it past its salad days. Thus, the founder’s “initial failure” to secure profits is thwarted and thrown back at the moderator who favors the glamour of profit over value-driven innovation. Segal sees through the inscrutable fog of failure and reaches out. “The intimacy of already having failed was the reason you could be more honest with certain exes than with any current lover.” In earnest, Segal finds the founder’s coded admission of failure relatable.

Like the depicted failure that eXe embodies in Mercury Retrograde, autofiction, too, is built on a shaky foundation. The last decade of autofiction has shifted away from coming-of-age stories written by or portraying artists discarding the common life for the glamour of their calling. This type of story, the “artist’s novel” or Künstlerroman, has all but disappeared. Autofiction of the ’80s and ’90s depicted unconventional, disintegrating narratives of artists-as-protagonists rejecting a provincial life in favor of realizing their artistic ambitions in The City. “I was all in one piece coming apart,” describes Eileen Myles, the poet-as-protagonist in Chelsea Girls. Myles crafts poetry while earning a living selling speed, cooking meals for the poet James Schuyler, and relishing sex with other women in a world that expects the opposite to be true.

Much like Myles’s melee, Chris Kraus eludes singular self-narrative coherence in favor of brandishing failure to cement her status as an outsider, an observer, an artist. In her series of artist novels I Love Dick, Aliens & Anorexia, and Torpor, Kraus details a semi-fictionalized career as a failed video artist with flat, pellucid projections cast upon her by more successful art stars like Nan Goldin, Dick Hebdige, and Jean Baudrillard. Against her failure, real or otherwise imagined, Kraus manages real estate property across suburban, Subaru America and writes. The artist’s novel’s magic, or scam, was that a novel a reader was holding was a byproduct of an artist’s failed art practice. Autofiction’s twentieth-century authors — in reality artists — recouped value from failure by turning to the novel as an alternative means of exhibition and reflection. The painful source of tension in these novels is the uncomfortable realization that posterity is mostly a futile project: our shared sense of failures, artists’ included, make us all the more alike. The Künstlerroman is a novel of fragrant leftovers, yesterday’s nutrients for tomorrow’s busier days.

Recent autofiction, however, short-circuits the Künstlerroman’s rejection of the mundane. Autofiction authors have replaced the artist-as-protagonist with the now ubiquitous author-as-protagonist. Under this direction, countless dreary tales abound in which The City offers zero refuge for professional authors and their prosaic copains. These author-as-protagonist characters turn inward, deceptively self-contained, and tell readers that the path to being a successful writer is to do just as they do: write about the failure of writing a novel. As a result, authors comfort themselves with unambitious tales about writing their novel rather than arresting readers with ambitious tales of novel living. Writers of these half-baked stories, from Sally Rooney to Ben Lerner, sell readers the shortsighted myth that monetizing one’s youth is a feast of souring just desserts.

Loosening up to predestination in SoHo the evening after the interview, Seth and Segal gather for feedback drinks that turn unmistakably flirtatious. However, the founder’s gloating attempts at seduction, which include bragging about having read Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer and attempting to lure Segal with dreams of imminent riches — “Think about it, Segal, a year from now we could be on a yacht, celebrating the IPO” — fall flat. Is it ironic that Segal’s eXe and its founders are in desperate need of a makeover? Reluctant to accept the job at first, Segal consults a spiritual aura reader, named Riva, to gain clarity.

“I feel like I’m about to make a huge mistake,” admits Segal. Riva confirms what Segal has always known, that there’s a cone of magenta energy pouring into her soul: she’s an artist, a cosmic creature from some faraway planet. According to Riva, magenta auras indicate that a human is on earth with a purpose to study and transmit high-level technology, like esoteric knowledge or experimental artwork, to the world and its inhabitants. Magentas, Riva warns, have poor relationships with authority figures and regularly move from one stimulating experience to the next.

Segal deliberates on the job offer and decides that the cons — she’ll have to leave her artist collective, K-HOLE — do not outweigh the pros: 1. Hot bosses, 2. Fast money, and, most importantly, 3. A giant opportunity. The opportunity is to create, on the company’s dime, a billboard in downtown Manhattan heralding the expansion of eXe’s library of texts and annotation capabilities. Segal decides that she’ll deliberately make use of the billboard as a publicity stunt that, in actuality, will be her first public art installation. The billboard-as-artwork won’t include eXe’s logo or any text. Rather, it will reproduce an illustration of a crawling baby inspired by a streetwear logo of an ape. Built into the landscape of New York, the billboard is her very own hermetic stamp on a city and history revolutionized by the infancy of the internet.

And, hopefully, the billboard captures the undivided attention of her most recent art crush, Marcus. Segal’s art installation approach is a nod to Marcus’s tech-inspired sculptures, like the collapsing pyramid of stacked white sheet cakes decorated in screen-printed corporate logos and PowerPoint slides she saw the previous year at a European museum. Marcus’s sweet treat delights in the gluttony and excess of imperialist tech startups accumulating vast amounts of wealth and power on the internet at the expense of social stability and durable innovation. She’s familiar with the grandiosity of embryonic tech startups. Her billboard, much like Marcus’s confections, revels in the contradiction that innovation is both sweet and wickedly fleeting.

* * *

We wasted a good crisis. In the digital effervescence of the past decade, a crisis has splintered our histories and cities. The inflection point, what stargazers might deem the “great conjunction,” occurred late one night at the end of 2020 when our solar system’s two largest planets, Jupiter and Saturn, converged in the portentous sky. The great conjunction designates a celestial turning point two hundred years in the making. From our vantage point on Earth’s soil, Emily Segal has forecasted that we have moved from a period ruled by Earth signs (“materialism, hierarchies, resource acquisition, territory control, and empire stabilization)” into a period ruled by Air signs (“the intellectual, the immaterial, and the ideological”). In all likelihood, you didn’t notice a shift that night unless you were closely following a beloved astrologer or hugging your telescope tight.

Artists, trend forecasters, and other custodians of the future have sought answers from the stars since the dawn of the millennium. Artists that emerged between the post-Occupy and pre-Trump years — the precipice that ushered in the great conjunction’s monumental shift — were concatenated by two camps: dissensus and reformist. Artist collectives, like Segal’s K-HOLE, were inspired by the techno-optimism, innovation, and disruption that cyberspace had fostered after the dotcom bubble and the Great Recession.

I refer to artist collectives working alongside the internet and toward the digital as “dissensus” artists. Artists provoked sweeping disruption through the internet. The digital drive championed speedy, widespread distribution of mythopoetic videos by Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch’s congregation, and post-ironic articles on fashion, consumerism, and self-parody by the aesthetes at DIS magazine. They left their day jobs and created their own corporations at the intersection of art and commerce; they built blogs and digital viewing rooms dedicated to the virtual avant-garde and undermarketed artists; and they dropped alienating university-speak in favor of witty, demotic lingo they found online. With the zeitgeist of the Tea Party and Occupy Movement, artists also gathered in masses.

Dissensus artists recognized their strength in numbers. Dissensus artists were practitioners deviating from the status quo found at dull corporate jobs, hard-to-navigate institutions, and decadent private universities. They situated their frustrated economic and social ambitions, described in detail throughout Segal’s Mercury Retrograde, in opposition to the artifice of the individual. Artists who worked alongside corporate feminism, gay-friendly nonprofits, and left-of-center magazines found a separate crisis of inclusion at work. Traditional institutions with administrative gatekeepers could not be easily thwarted and remolded through liberal self-determination. A whole generation had grown disillusioned.

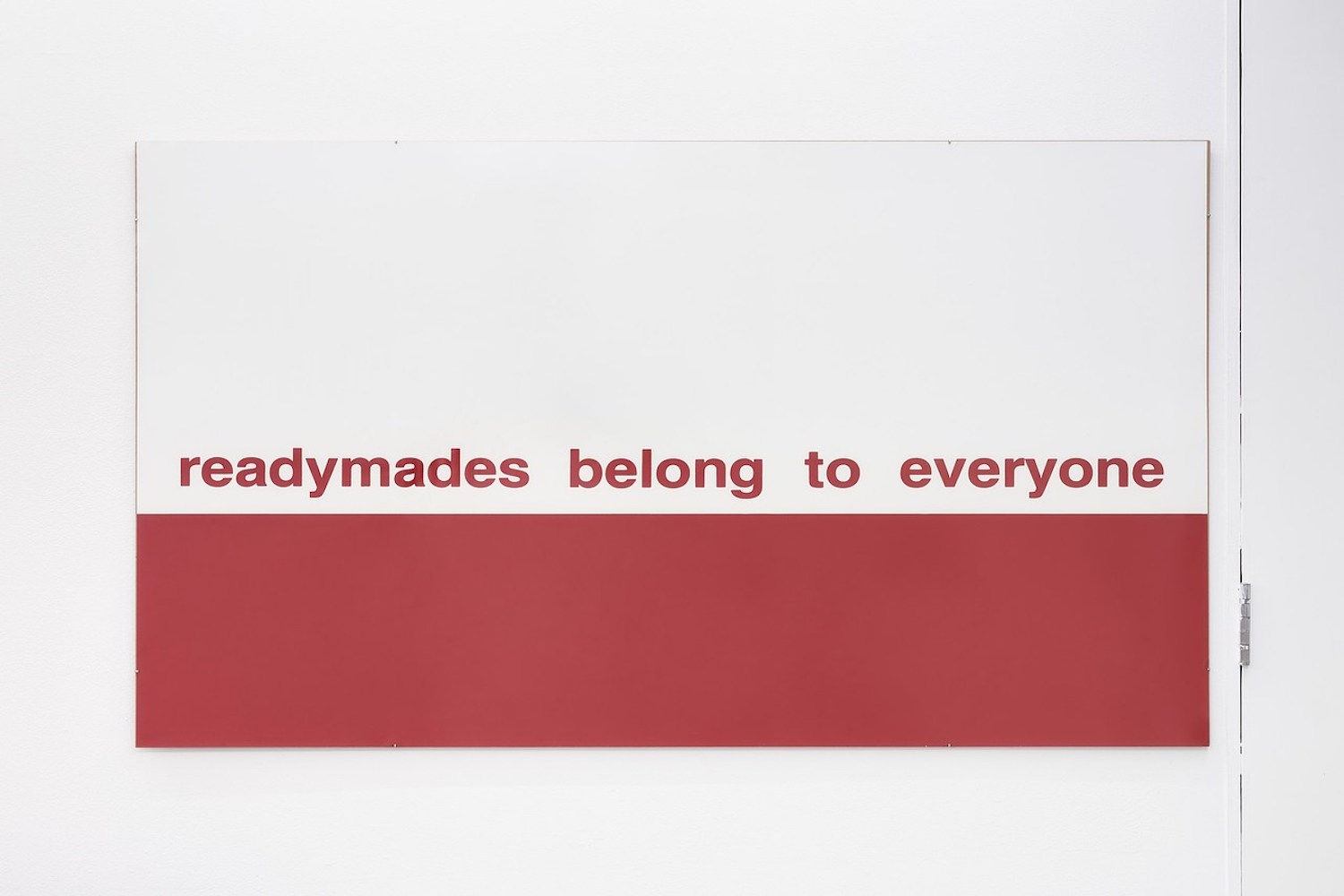

Distraught, cerebral artists adapted and embraced the internet’s embodiment of the postmodern aesthetic of fragmentation. Artists compressed and converted artworks into JPGs (images), PDFs (documents), and MP3s (videos). Once downloaded, digital versions of artworks could be launched onto a curator’s phone or a friend’s laptop all free of cost. While digital disorder became the dominating, invisible currency that fueled online social interaction and produced an abundance of real-world artist collectives, another camp of artists came to prominence alongside the dissensus, a group that might be called “reformist artists.” The reformists’ art was animated by a different set of concerns. They were drawn to the ethos of dissensus artists but reacted against the digital, the artificial, and the techno-optimism that guided their peers.

By choosing to break with dissent, reformist artists sculpted heroic narratives and used the internet as a tool rather than a medium. Reformists petitioned and successfully ousted suspect museum board members and donors who were in the pathetic business of selling chemical weapons and addictive opiates. Painter and sculptor Nicole Eisenman has split a prized solo exhibition and accompanying catalogue with scatological painter Keith Boadwee in an effort to expand resources and exhibition space. Beyond the museum and its twenty-first-century ruins, playwright Jeremy O. Harris has allocated a significant portion of ticket sales from their Broadway-backed play on the thrills of sex and love into funding for emerging writer’s grants; and fashion designer Telfar Clemens has broke the internet several times over with the guaranteed-upon-digital-purchase vegan-leather-strapped handbags worn by progressive politicians, housewives, and ingénues around the globe.

These new custodians were uninterested in the reactionary, sometimes trolling, gestures of their peers. The dissensus’s death-drive-into-the-future sensibility would eventually be absorbed by the digital far right and lead to an unforeseen period of political grift and depraved self-interest. Neo-reactionary nerd subcultures found on websites like 4chan promoted the aggressive antics and cronyism rampant in both Donald Trump’s strain of secular conservatism and Peter Thiel’s style of corporate libertarianism. Reformist artists diverted excess creative entrepreneurial energy into craft, the archive, and techno-pessimism in an effort to fix what was broken. The reformist wave of artists were less interested in spiraling negation and, instead, motivated by a post-digital pleasure principle.

Unlike the dissensus artist, the reformist artist preferred to minimize and divert psychic tension from changing social and economic trends. Still cautious of the overdetermined emphasis on the individual, reformist artists looked to their peers, friends, and lovers as sources of libidinal and Romantic inspiration. In earnest, they painted social worlds that have not been documented for centuries; they weaved interior narratives in resistance to surface-level appeals; and they took to journalism to point out nauseous abuses of power. The Apollonian to the dissensus’s Dionysian, reformists were curators of charisma and shared a predilection for material inclusion over digital chaos. The value-driven ethos of reformist artists espoused the evolution of an avant-garde once again interested in rehabilitation.

Rather than turning to the internet as a platform for artwork exhibition, reformists used the internet as a tool to reach audiences directly. In doing so, they offered their followers practical advice, humbling hot takes, and routes for navigating an increasingly complex world that favors credentialism over inherited power. Reformist artists also satisfied the demands of a public with greater access to private spaces and a growing trend to document lived experiences online. In exchange for creating large-scale social environments that fueled the rise and reign of the experience economy in the 2010s, reformist artists demanded progressive, often humbling, changes in leadership and accessibility at private and public institutions. As Telfar’s slogan councils, reforming our present offers a glimmer of hope: “Not For You — For Everyone.”

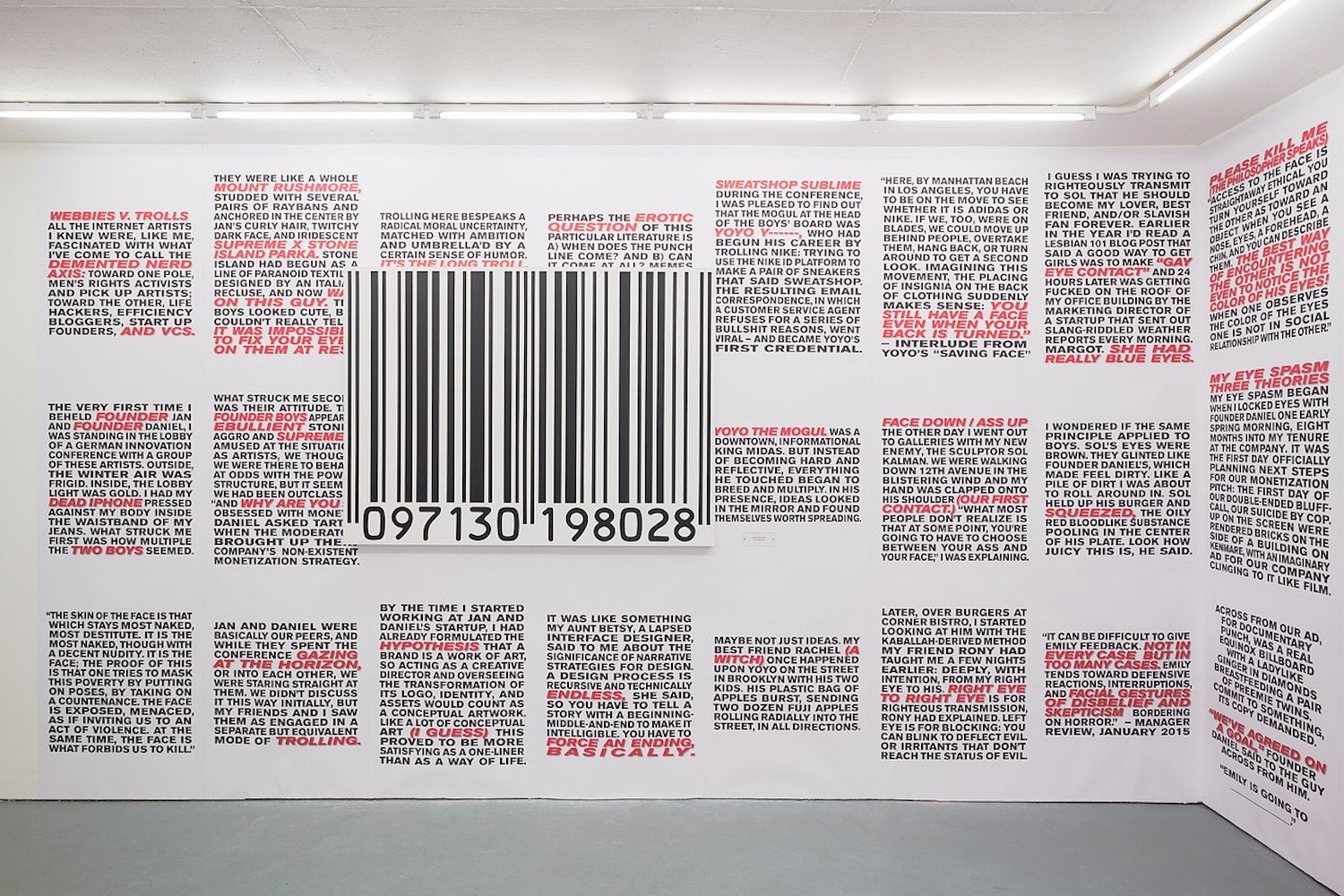

Earlier projects by dissensus-era artists evoked similar, overlapping populist conspiracies. “Once upon a time people were born into communities and had to find their individuality,” muses K-HOLE’s trend forecasting report Youth Mode: A Report on Freedom (2013), which is described in various anecdotes throughout Segal’s Mercury Retrograde. Youth Mode, a legendary hallmark of dissensus-inspired art, continues: “Today people are born individuals and have to find their communities.” K-HOLE’s cohort of artists were eager to break free from the doldrums of Obama-era culture that was frequently reinforced in commercial forecasting reports. They were looking for a departure from a climate that celebrated retro concepts centered around individualism such as authenticity and difference.

Commercial forecasting trend reports, however, predicted with uncertainty what trends may come next for young urbanite consumers. K-HOLE’s reports captured a commercial report’s speculative uncertainty and transformed the anticipation into something more expansive and urgent. The collective’s PDFs took simple ideas — for example, “Shoulder pads from the 1980s will see a revival after our historical inauguration this winter” — complicated them with corporate-speak, and rebranded the ideas as trends-to-be. The digital reports remixed caustic sociopolitical concepts with photoshopped internet stock images and lyrical corporate platitudes. If anything, the documents read like twenty-first-century self-help guides by an imaginative online intelligentsia.

Widely circulated overnight, K-HOLE’s Youth Mode sprang up in email threads and text exchanges between sleepy journalists, zombified luxury brands, and fashion opportunists around the globe. In reaction to the mainstream culture that dissensus artists so despised, K-HOLE proposed normcore. Normcore celebrated situational adaptability, which, according to Segal’s collective, was the freedom to be with anyone instead of the freedom to be anyone. Journalists misinterpreted the long-sleeve sweaters and button downs, clean Nike sneakers, and additional bland fashion imagery within the document as the material codification of what students of normcore should study. Ironically, K-HOLE had no responsibility for normcore’s cosmetic second life, which further established the trend’s linguistic importance as the 2014 runner-up in Oxford Dictionary’s word of the year.

Reflecting on the course of events while writing this chapter of her life, Segal shares, “I had been embarrassed by all the ways normcore had been eaten up by brands and the media, the [unauthorized] Michael Kors ‘NormKors’ collection for example — I thought it was just humiliating, but if we were trolls then maybe we could see it another way… Could you be trolling and believe in it at the same time?” As with any kind of self-mythologizing, I wonder, too. But artists, especially those who embrace the path of social rejection realized in the novel, the new, are routinely punished for their hubris. “The feelings of failure, the paranoia, the taking everything personally — I marveled at the granularity of it, the endless multitude of points onto which one could pin a suspicion or a proof of failure. A big theme was that I was a plagiarist, a person who takes credit for other people’s work, and that I couldn’t even do that well. Non-artist, bad marketer — a smoothie of contemporary nothing.”

Artists sabotage themselves by stepping into histories and cities that never belonged to them, punished by the gods for their hubris. As evidence of this drama, US courts in 1990 awarded David Wojnarowicz an embarrassing $1 in damages after minister Donald E. Wildmon of the American Family Association (AFA) distributed a brochure that included, without the artist’s consent, fourteen cropped and recontextualized homoerotic images from different Wojnarowicz artworks.2 While Wojnarowicz provided primal narratives of self-love to a city that had recently decriminalized sodomy and other non-procreative sexual acts, both in his paintings and his Künstlerroman, Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration, many American courtrooms remained bitter over shifting cultural attitudes. The artist’s $1 settlement was justified by the judge, as well as the defense attorney, who pointed out that a scandal would increase interest in the artist’s work, as did analogous scandals endured by Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe. Wojnarowicz’s paintings, however, did not rescue him from the poverty he was told he would escape. The artist succumbed to an early death from HIV/AIDS two years after the ruling.

Seeking to avoid similar judgment by the gods, some artists, such as Ryder Ripps, may opt out of creating their own histories or cities and instead create narratives in worlds that exist entirely online. Ripps is an artist-turned-author. He has abandoned exhibiting paintings at galleries in favor of designing logos and other computer-generated graphics for brands like Marc Jacobs, Soylent, and PornHub. As an author, he tells a brand’s story through bold, boxy typefaces and dripping serif fonts. Much like Ripps’s journey from artist to author, Segal’s Künstlerroman is a novel about opting out by selling out. It’s also a novel that brandishes and parodies self-aggrandizing behavior, one of the animating passions of literature and art in a decade haunted by the recursive nature of the internet.

While our digital identities hinge on anxious self-expression and promotional difference — “disruptions” — in reality, our shared sense of uniqueness makes us all suspiciously similar. On the topic of our decorative identities, both in print and online, writer Natasha Stagg shrugs, “Straight men are obsessed with sex, gay men are obsessed with form, women are obsessed with themselves, the internet is an obsessive habit.” For adherents to the dissensus, our obsessive and obnoxious online habits prove our tragic likeness. In response to dissensus-era disenchantment, a genre mislabeled as autofiction has calcified against the unambitious spectacles of the twenty-teens: the artist’s novel.

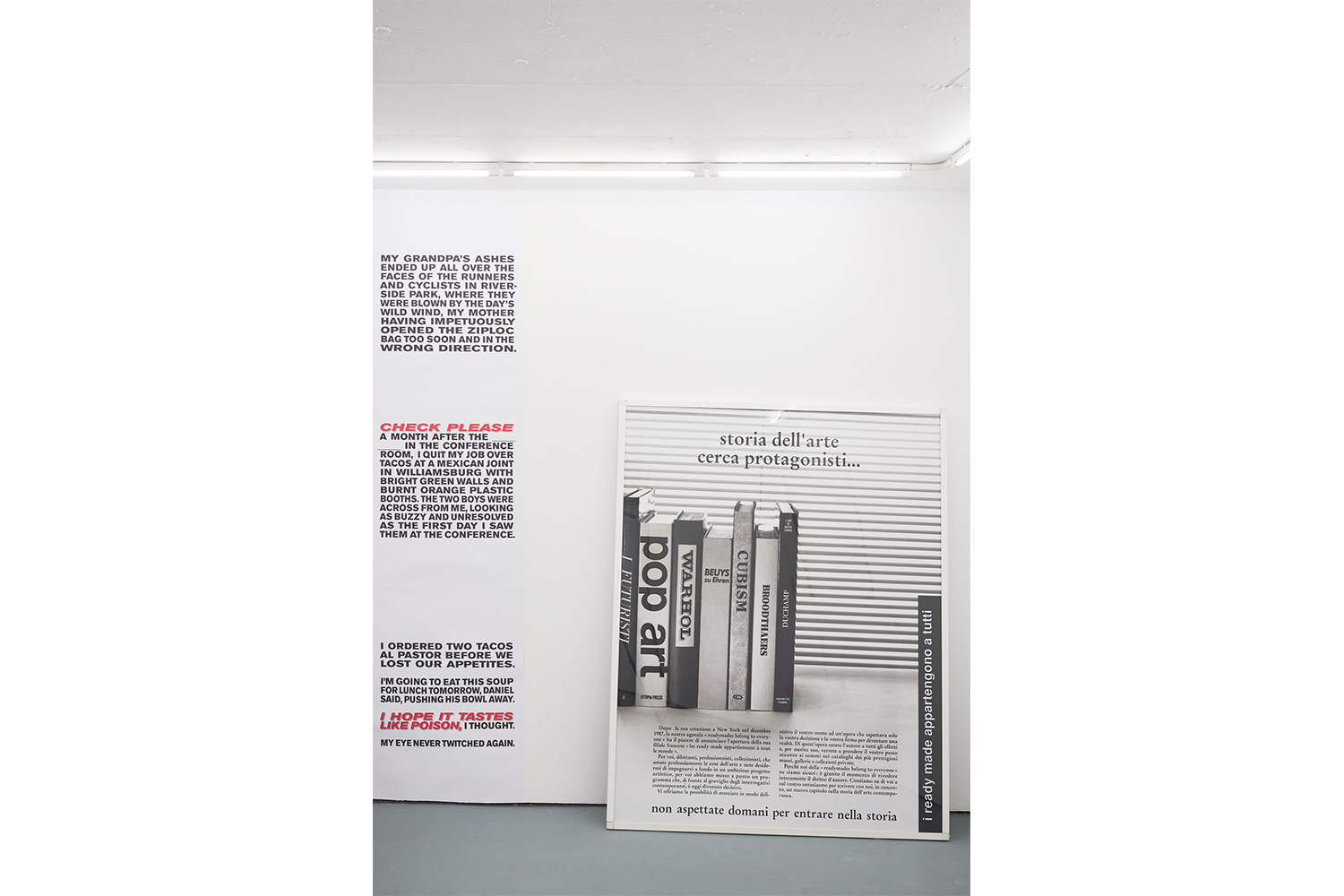

At the closing of Segal’s Künstlerroman, the artist rejects the cozy embellishments found at eXe in favor of settling into her magenta aura. Through corporate restructuring motivated by the founders’ accelerating insecurity and maturing debts, The Boys rework Segal’s duties at eXe and incorporate unfamiliar responsibilities in sales and marketing. Segal has one month to raise $1,000,000. She quits. And with this decision, realized through several epiphanies (on an updated definition of Mercury retrograde: “It could stand for the opposite of ‘failure’ so celebrated in the startup landscape in which I dwelt; it was the disruptive twin of Disruption”) and deft digressions (one chapter, titled “Fuck, Marry, Kill,” satirizes the essential trauma as punishment inflected by parsimonious ex-boyfriends, not imaginary gods), Segal breaks from her dissensus-style decision-making. “I aggravated people with my harshness, so I needed to cut the line and get ahead early, before people’s irritation could really sink in; to work with that magenta energy instead of against it.” Exhausted, her eye spasms come to an end; the fog of failure starts to lift.

Late one evening after boozy drinks with Marcus, however, Segal learns of an unexpected betrayal from her impish friend: “You know they’re hiring me, right?” Peter Thiel, gay entrepreneur and venture capitalist, has swooped in to supply eXe with an additional round of funding. The funding comes with the condition of hiring emerging creative talent Marcus. Defeated and once again punished with Mercury retrograde, either by the gods or an impoverished eXe, Segal turns away from the digital and begins to write her novel. And, unlike the selfie-styled novels of her peers, stuffed with self-aggrandizement and drunk on idle success, Segal’s novel debases form, replacing the dead author with a living artist.