If I say “pumpkins and turbans,” the first thing that comes to mind might be the edible squash called a “turk’s turban,” which can be roasted, baked or steamed, and is a popular choice for ornamental autumnal displays in gardens or stores. In a work by artist Füsun Onur entitled Souvenir de Dolmabahçe (1992), these references come together to relate to a given space. In 1992, in a park, she installed four garden chairs covered in white tulle in a linear arrangement divided into groups of two by three plaster plinths. These were linked to the chairs with white cords and bands, some with gold writing that read “Souvenir de Dolmabahçe.” On top of the three plinths were placed three huge pumpkins. Viewing the piece, one could see that its rhythmic quality corresponded playfully with the flowery architecture of the building on the side and the high walls surrounding the well-kept garden. The work’s source of reference was a mid-19th century Ottoman monument, the former Imperial Dolmabahçe Palace, assigned to the Academy of Fine Arts in 1937 to be inaugurated as the newly founded republic’s first Museum of Painting and Sculpture.

Analyzing the conceptual distinctions between public space and private space in Turkish architecture, academic and writer Uğur Tanyeli scrutinizes the terms “private” and “public” in relation to their synonyms in English. In his essay “Public Space/Private Space: The Invention of a Conceptual Dichotomy in Turkey” (2005) he pins down the equivalents of the words in Ottoman Turkish in a 1860 Redhouse Dictionary: the corresponding meaning of “private” is “halvet,” which, prior to its use in 19th-century Turkish, referred to the individual place of prayer and invocation, the place in which to speak secretly with God without ever being heard, or a personal washroom in traditional Turkish bathhouses. So, Redhouse equates “private” with “being secluded, secret, clandestine, concealed, hidden, intimate, as well as that which is not official and administrative or commercial”; “public” is a space that is “related to the people, to the nation but particularly to the state and the central government.” There is a paradox here that is not only linguistic but cultural. In fact, another translation of “private” into Turkish is “has.” In common classical Ottoman it refers to what belonged in the sultan’s name, in terms of qualifying an imperial monument or group of individuals committed to public duty in a mosque, army, bakery and so on. Tanyeli observes that when the Ottomans became integrated with the Western economic and cultural world in the 19th century, they had to adapt; until then “public life was simultaneously private and public.”

In the garden of the Dolmabahçe Palace an intricate game of transformation of this sort is underway: the Baroque and Rococo ornaments of the façade’s eclectic architecture that repeat on the walls dividing the palace from the surroundings are bent by Onur into an idea of music, which is then delivered into the rhythmic form of an art installation that is made with furniture collected from the site and combined with organic elements. The ephemeral presence of the pumpkins rises above the white plaster plinths and contrasts with the latter’s original function as structures of support for perennial and worthy objects. The pumpkins mimic what is actually missing in the place: the opulent turbans of the palace’s former owners.

Onur’s intervention marks the land’s myth and history before it silently dissociates after the period of its exhibition. It secures the garden as a place of remembrance, and the artwork as a brittle “souvenir” of that place. To the memories associated with the place, Onur adds her own personal history as an artist, declaring the garden as the place for production as well as exhibition. The site of the former imperial residence and the actual art institution, where a complex process of dislocation and relocation takes place, blurs the territorial boundaries between the private and the public.

Specific works by Cevdet Erek, İnci Eviner, Sarkis, Serhat Kiraz, Aslı Çavuşoğlu, Deniz Gül, and İz Öztat share with Souvenir de Dolmabahçe a certain sensibility towards place as context, situation, site and concept to respond to, reproduce and destabilize. In all these works, place, with its institutions, rituals, mythical narratives and practices of daily life, becomes the object of an artistic curiosity and individual expression. Everyday objects collected from that place become artistic material to undo, redo and interpret. Definitions and perceptions of a place that is delimited by institutions of the nation, state and central government are deconstructed, and the place itself becomes a situation of subjective relations and associations.

Both Serhat Kiraz and İz Öztat turned the site of 35-year-old Maçka Sanat Galerisi, a mythical Istanbul gallery, home to generations of conceptual art, into a mental space of remembrance and reconstruction. The artists took critical stances in relation to the rich strata of history and mythevoked by the place. While Kiraz decided to engage rationally with its architecture through mathematical calculation, Öztat delved rather intuitively into the archives of the gallery to tackle a set of questions relating to tradition, history and cultural heritage in the production and display of art.

Kiraz’s Construction / Reconstruction (2007) invoked a question that François Morellet posed to the artist upon visiting his site-specific work presented at the gallery in 2002: “How could you ever bring such work to France?” After two years, Kiraz reconstructed the gallery space inside a museum in Cholet, France, based on a computer rendering. The installation was a two-dimensional Rubik’s cube, composed of a number of two-sided surfaces with fragments of four different views of the gallery space imprinted on them. The piece effectively asked the viewer to compose the completed view on one side of the structure, while a fragmented view on the other would automatically occur, such that the three-dimensional perception of the space would be constructed in the mind of its beholder. Three years later, he “reconstructed” the exhibition in Cholet in the gallery in Istanbul with documents of its realization. Kiraz shipped the memory of the gallery back and forth twice, and on the journey back home he forced a moment of confrontation. What is constructed and reconstructed: the image of the gallery in Cholet or that in Istanbul? Does the image of a space contain the experience of that space?

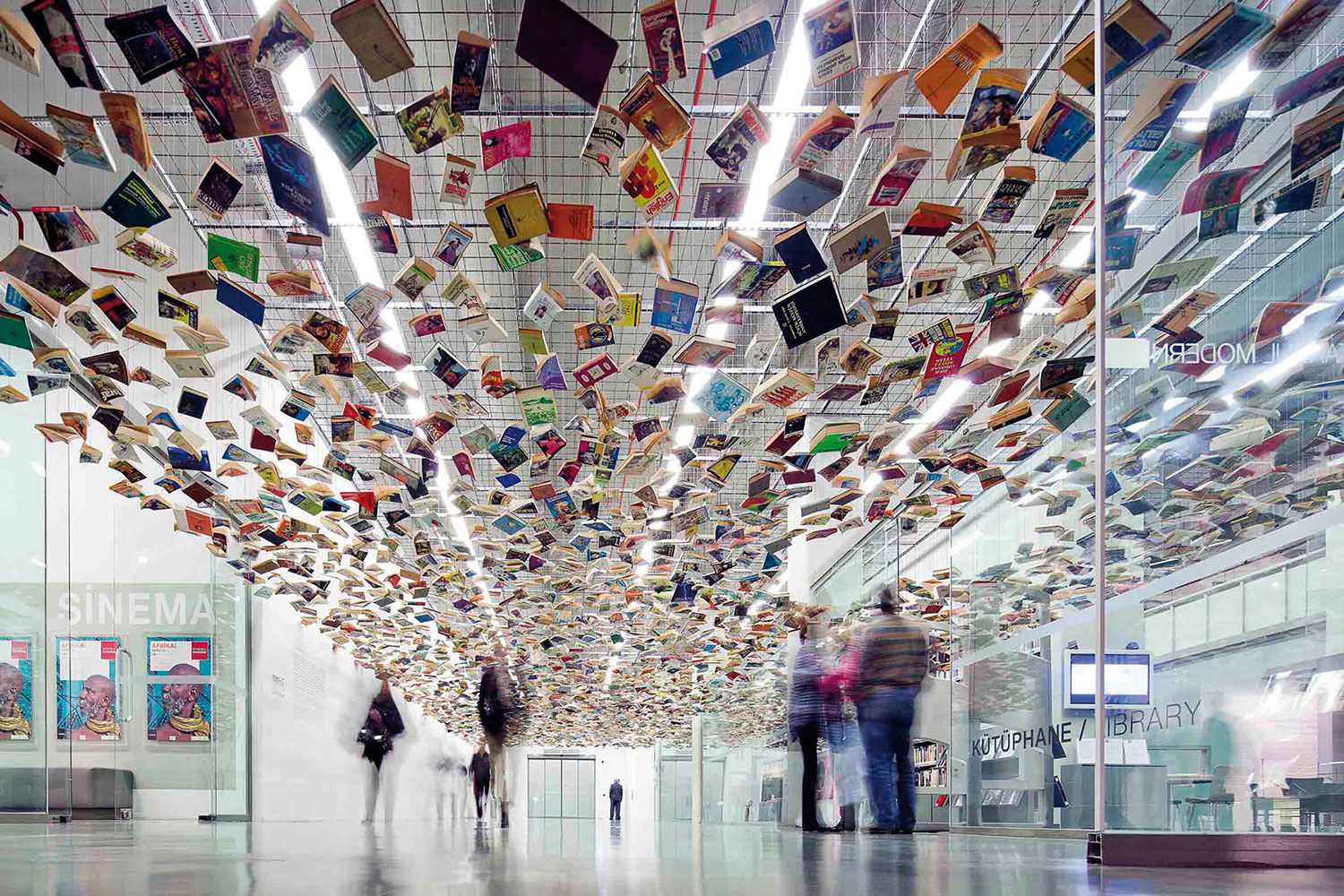

For his 2009 retrospective at Istanbul Modern, Sarkis included a large number of life-size images of works and installations alongside a few actual works. It confirmed the understanding of the work of art as material to be used again and again — done, undone and redone. The title was “Site,” which in English means the place where something is fixed, a location or a situation, whereas in Turkish, the word “site” is used to define a housing complex. The show presented art as a process of constant creation, and the exhibition space as a place where memories of the work’s previous lives collide.

Öztat’s solo show titled “IZ,” which took place at Maçka Sanat Galerisi earlier this year, also looked toward history. A series of performative actions, both live and recorded, were dispersed into the labyrinthine spaces of the gallery. A wooden sieve, a copper dome, a red lacquered wooden triangle object and a lifting net, all found and sometimes modified, were used by Öztat to performatively measure the ceramic-tiled interiors of the gallery space. The performances’ intellectual background was provided by inspirations and influences found in the 35-year-old archive of the gallery. Sound recordings of artist talks held in the past three decades were used by Öztat as raw material. The way human sound was distributed in whispers and shouts in the space made the viewer and listener aware of her/his body and orientation in the space: walking slowly or quickly, standing here or there, closer to one speaker or another, closer to the wall or the door, tracking the voices while trying to understand.

An untitled collage by an unknown historical figure named Zişan, born in Istanbul in 1894 and declared by Öztat as her guiding spirit and alter ego, was included in the show. The collage showed the black and white photograph of a woman in a miniskirt holding a barbell with a pumpkin and a turban fixed to either end. Inspired by this, Öztat produced the object in three dimensions and included it in the show. In this way she addressed the accumulative history of the place with a set of questions relating to the weight of the past and its influence on artistic production.