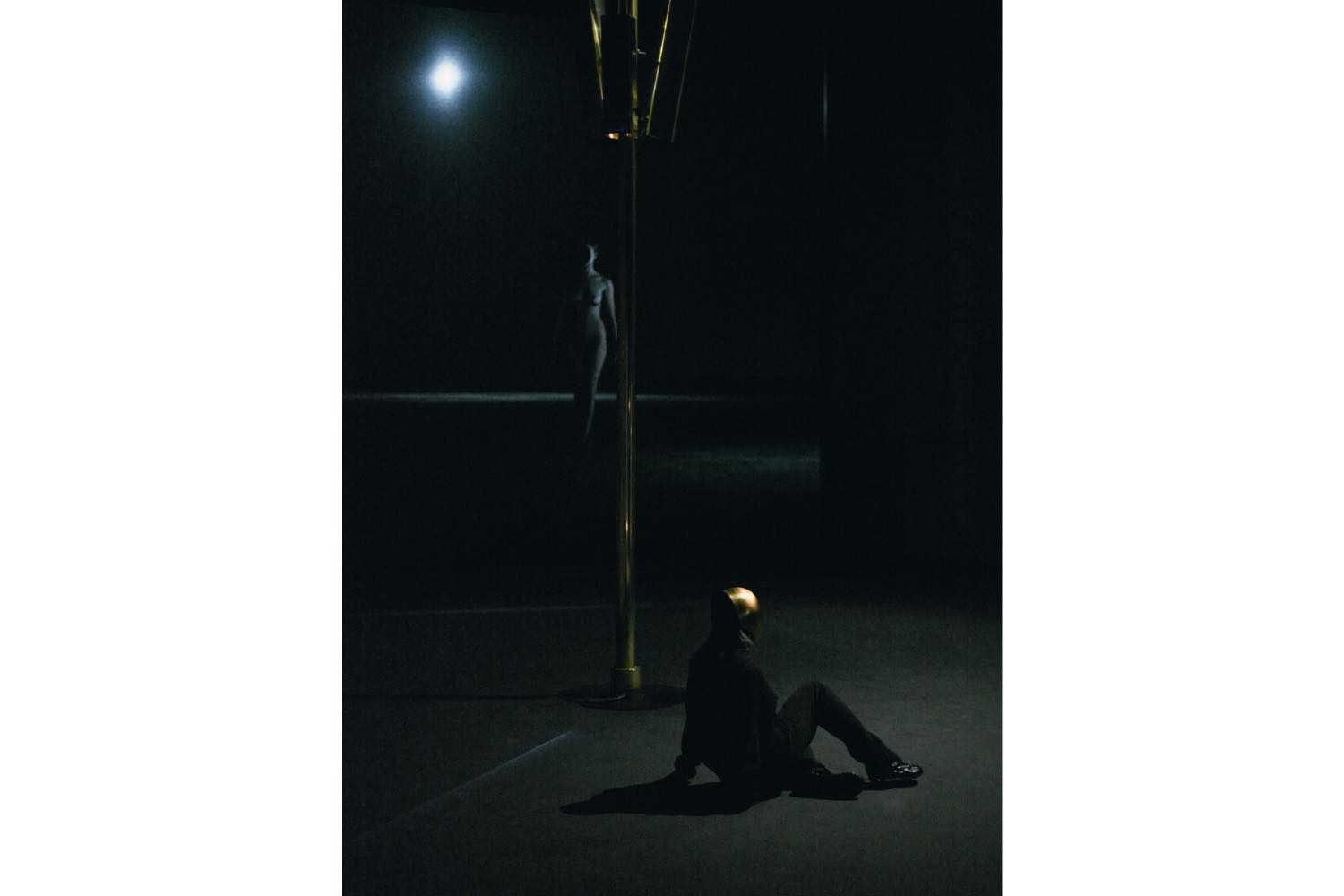

There’s an enigmatic peculiarity to Pierre Huyghe’s work, a riddle one can easily get lost in and miss the more significant expression. When I asked him about his new exhibition at Punta della Dogana in Venice, Huyghe told me, “I would say that if you are facing something impossible to understand, that is where partly I want the work to bring you to this momentum of complexity.” The title of the exhibition, “Liminal” — a term used in ChatGPT press releases as frequently as “Anthropocene” several years prior — is also the title of the first work upon entering Punta della Dogana. The show consists of several new and past works. Liminal (2024) is a film projected onto a large transparent screen and features a nude woman alone outside in the dark, pacing, crawling on the ground, and looking up to the heavens. Eerily, she has no face. Where the face should be is just a black void of nothingness. In a particularly affecting section of the video, she holds her hand up to the void, sensing what isn’t there. But how can this being function with a hollowed head? She isn’t a living person, but a 3-D model Huyghe created, an incredibly realistic avatar. Her appearance is so authentic that Instagram censored my post and deleted the video, stating it “may go against our guidelines on nudity or sexual activity.” Liminal has an AI component that controls the woman’s actions; the camera and she respond to sensors in the room of the installation. With artwork generated by AI I often wonder if it is the labor of a Mechanical Turk rather than technology performing human like tasks. Over inquisiting can be like Toto pulling back the curtain towards the end of The Wizard of Oz. It is often best to focus on the spectacle of the artwork itself and “pay no attention to that man behind the curtain.”

This exhibition appears to be a liminal period for the artist himself. As François Pinault remarked, “The project, conceived and refined almost up to the last moment, constitutes, in my view, a new step forward in his work, which already placed him among the most remarkable artists of our time.” I asked Pierre about the compliment, and he appeared slightly uneasy. He slowly responded, “I think with this exhibition, a bit, it’s the same. You always do the same; somehow, you never stop doing the same. But I feel that this exhibition is a larger step toward a shift in my practice. And I think maybe I’ve come to have the feeling that now there’s more superposition of, as I say, plan of reality, and the feeling that the constitution of different subjectivities is growing and taking shape. They start to gain voices and presence, even if the self is still fragile and shifting. But they are in existence.”

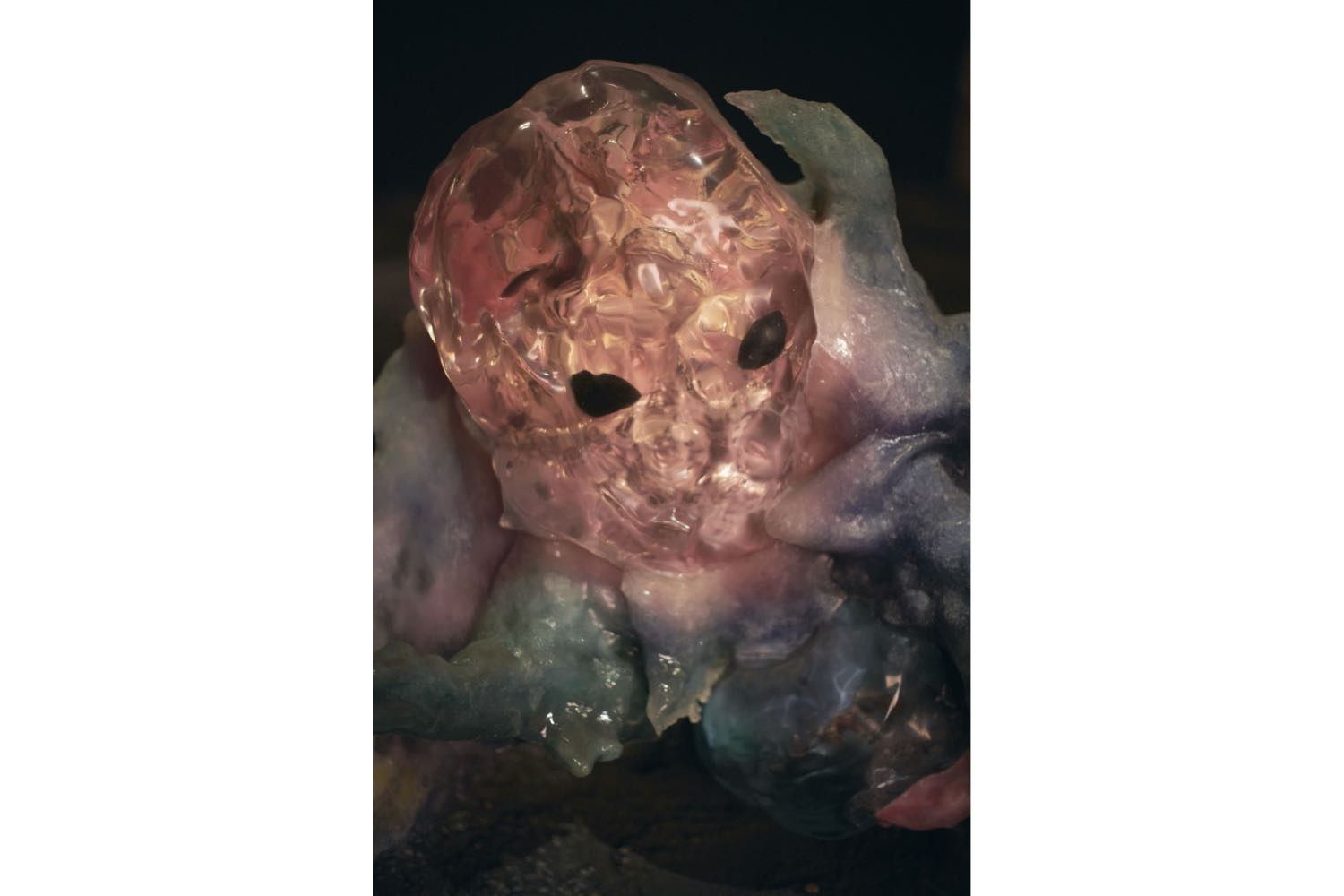

The nonlinear space and circular design of “Liminal” is meant to get lost in, I’m told by curator Anne Stenne, who has worked with Huyghe for a decade. Turning a corner, I find myself in a gallery filled with the artist’s aquariums. It’s one of the brightest rooms in the museum but still obscuringly dim. These aquariums are some of my favorite artworks from the twenty-first century. Zoodram 6 (2013) — a fish tank with a crab living in a resin mask based on La Muse Endormie (1910) by Constantin Brancusi — is the star. Like many of Huyghe’s works, these tanks must cause migraines for conservators: When this artwork isn’t exhibited, where does it exist? In one of Pinault’s several homes? And what about the crab? Is this the same one I saw last time? Fortunately, the museum had not yet opened during my visit to Punta della Dogana. I catch two employees with a ladder and long mechanical claw picking out a tiny pellet of food the sea creatures didn’t eat. Gleaning acts of maintenance required to sustain the conditions of the pristine environment feels nearly illicit.

In today’s “vegan-activism-Instagram-world,” it’s incredibly bold to work with living organisms. For Huyghe, this might be necessary in order to contrast the more ambiguous AI entities: the real real and the artificial real. I’m curious if Huyghe ever ponders digitally resurrecting past living beings from his immense oeuvre — Human, for example, an enchanting Ibiza hound who died in 2022. One of my fondest memories of an exhibition is following Human around the galleries of LACMA during Huyghe’s retrospective in 2014.

Pierre Huyghe is the artist’s artist of relational aesthetics. Studying in Paris at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs and later at the Institute des hautes études en arts plastiques, he encountered Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and Philippe Parreno and several other artists who formed this movement. Nicolas Bourriaud, in his pivotal 1998 book Relational Aesthetics, defined the sensibility as “a set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space.” I asked Huyghe about his connection to his former classmates. “In life, you encounter other people who have lived, creating interference in your way of thinking. And to me, it’s always been important to be disrupted or affected by other minds and to be entered by other minds. And so, it has always formed a polyphony somehow.”