From Flash Art n°150, 1990

Giancarlo Politi: Someone like yourself, an intellectual, self-possessed and reflective, can you enjoy the act of painting itself?

Peter Halley: I do like to paint and I’ve liked to paint ever since I was a teenager. Everybody thinks I don’t make the paintings, but I do. At first I thought I might be the kind of artist where somebody else could make the paintings, but now I think that someone else would either make them too well or too badly. When I make them they’re not perfect; if someone else were to do it, they might do them so cleanly and precisely that the paintings would be different. I don’t like to paint difficult things where one has to work out shading etc. I like to paint flat surfaces and I like to paint mechanically. But it’s really different from someone like Robert Ryman, because a Ryman painting has so much sensibility. There’s something enjoyable about doing something simple, and in my case it’s pretty mechanical or without reflection. I’ve always been interested in the kind of abstraction in which the artist’s way of making the thing has a lot to do with it — whether it’s Mondrian or Barnett Newman or Frank Stella. In particular Stella has always fascinated me because his early work is so sloppy, the lines aren’t straight and the colors bleed, and yet it gives the work so much personality.

GP: You are also the theorist of your work. What is the relationship between theory, your writings, and the work itself?

PH: I’m not writing very much anymore, which seems kind of interesting to me. I set out to write in order to verbalize what I was trying to work out in the paintings of this kind. I’ve always considered it as background information and a way of talking about specific phenomena in the culture. When I wrote about airports or highways it was a way of expressing my observations or reactions to those things, which I couldn’t directly depict in the paintings, which are a much more condensed, or abstract project. What’s taken over for me, instead of writing, are various kind of projects, such as the things I’m doing in printmaking. The prints are based on diagrams of computer systems in offices. It’s a subject that interests me a lot but I can’t put it directly in my paintings because I want the paintings to be purely about a certain kind of space. In a print I can discuss it.

Giacinto Di Pietrantonio: Is there any influence between your interest in philosophy and other cultural areas and your work?

PH: I try to be very specific about this. I really can’t read pure philosophy. My entire interest is in critical theory and social theory, but somebody like Jacques Derrida or Martin Heidegger is just beyond me. In fact I’m not even that interested in critical theory except as it relates to the visual world. The kinds of authors that I’ve been involved in are those that are trying to examine the space of our society, particularly Michel Foucault, Guy Débord, Jean Baudrillard and Paul Virilio. It’s not so much a question of being influenced by them; these people are interested in the same things that I’m interested in, but they’re exploring it in one discipline and I’m exploring it in another. In recent years it’s became apparent that Baudrillard doesn’t have much interest in the visual arts as we understand them, but that doesn’t bother me at all. He’s interested in what’s going on visually and spatially in our culture, and that’s what I’m interested in as well.

GP: What is the difference between your work and the European Constructivism from the ’60s, or artists like Ellsworth Kelly and Victor Vasarely?

PH: Those movements in the ’60s saw technology as a liberating thing. I think that at this point, 20 or 30 years later, we’re very far away from that. Probably the chief disillusionment of the ’60s is the failure of our belief in technology: by 1970 that kind of technological optimism is almost gone. The same is true with neo-plasticism and constructivism — they also posited both technology and rational geometry as an ideal that would allow society to rationally improve. I always say that the art was abstract because it described a situation which did not yet exist, that of a totalized, rationalized environment. People then imagined that when such an environment came into being it would be utopian. I would say that we’ve reached a point in which that totalized situation almost does exist and it’s not utopian, it’s something you have to examine rather carefully. But it’s also no longer the future, it’s the present, and in that sense it’s no longer idealist and abstract but rather real and dystopian. One of my particular concerns in terms of this process is the computer. The computer in a sense can be seen as the culmination of all Cartesian thought. Yet since so much information now goes into the computer, and the computer now mediates so much thought, I think we’re stuck with something that limits thought or that controls thought in a way that’s rather troubling.

GP: In a way you represent the ideal artist of the end of history…

PH: I’m very strongly attracted to this idea of the end of history; my 1982 article on Ross Bleckner was called Painting at the End of History. This idea of the end of history in the Hegelian sense is one we all have to come to terms with somehow or other. It’s not to say that the end of history is going to be replaced with something better [laughs], but history, as it exists in the modernist sense, from the enlightenment to the present, is something that is being increasingly challenged both in the culture and by intellectuals. I just don’t see how we can go on thinking about history in that traditional way. Those structures and lineages and categories just seem to me to be too discredited at this point.

GP: Christophe Amman told me that maybe the strongest country right now in art is Germany, because it is the only country where attention is really paid to their post-war condition, the only Western post-war country. Do you think that important art can only come out of a post-war society, or in a society which has experienced a strong conflict?

PH: I would agree with that, however, for me it’s hard to read Germany right now as a particularly post-war society. To me part of the increase of creative and artistic activity in Europe in the ’80s has to do with the fact that I think at some point in the decade people were able to say “the war is over.” What fascinates me about Europe in general is that we’re now really dealing with a post-post-war Europe, a Europe in which the reconstruction is completed and life can go on.

GP: You are thinking of the wall in Berlin, of the division of Germany,1 and this is certainly a major trauma for them, but I was referring to the fact that they still seem to live in a state of war. They still can’t believe in peacetime as their eternal condition…

PH: That is a very real phenomen but I wouldn’t so much connect it with World War II. Rather, it’s one of those strange situations which developed after the war in which the historical idea of the nation/state begins to break down. Clearly, Germany as a nation-state is somewhat transformed or dismembered; it seems to me that some of the most interesting places in the world right now, be they chaotic, tragic places like Lebanon or strange constructs like Israel, are these kind of postnation-state entities. They are very charged sites right now. Actually, there is a connection with American artists too; some of the people who I think are doing the best work right now, like Haim Steinbach, Meyer Vaisman, or Saint Clair Cemin, are the products of several different sequential cultures. They were born in one place and then they grew up in someplace else and then they came to the United States, and so their view of culture is not that of a person in one place with one culture. Perhaps that’s another thing that’s developing in terms of the cultural outlook of artists today.

GP: Don’t you think that this internationalism corresponds in a way to a strong explosion of nationalism in politics and even in culture? I’m thinking for example of Russia, in which every region has its own culture, its own painting. I’m sure that even Islamic nations are more or less expected to express their culture in visual art.

PH: That is perhaps another side of the same phenomenon, that localism could also be seen as a rebellion against the nation-state. But, getting back to the subject of Germany, I would agree that it’s kind of a charged environment for many reasons, and I guess I would agree that the separation of what used to be a nation-state perhaps is part of it. But there’s such a high degree of affluence in Germany and it’s such a closed and perfect social web, one also wonders what the effect of that on art is.

Giacinto Di Pietrantonio: Your work deals with abstraction, which originated in Europe, but your work also reflects American art, pop art, in the use of fluorescent colors, also found in certain American minimalists, like Donald Judd. You seem to be a point of convergence between European and American trends.

PH: Well that’s very complimentary. I see Judd and Stella in very much the same way. With Donald Judd, there’s such a strong connection to Europe in the strategies he uses in terms of proportion and that sort of thing, and yet at the same time the plexiglas and candy-colored surfaces create a technological connection to the United States.

GP: Are you considering working in sculpture?

PH: Actually I’m experimenting with the idea of low relief, because I’ve always considered the paintings to have a relief element in terms of the Roll-a-tex texture and now also the raised conduits. But what is normally thought of as freestanding ‘sculpture’ has never appealed to me, because I’m more interested in the world of intellectual or diagrammatic projection rather than in real spaces. One of the basic premises of my work is that the flat, two-dimensional, diagrammatic space of our culture is more important than the three-dimensional objects in it.

GP: Could your work be seen as flat sculpture, and how do you view three-dimensional painting?

PH: I like the idea of thinking of these as flat sculptures [laughs]. I find that one of the strongest formal trends in painting today is the idea of three-dimensional painting whether practiced by Elizabeth Murray or Stella or someone like Meyer Vaisman. The fact that they’ve moved into a three-dimensional space and are able to do all kinds of fantastic things with it I find very interesting. But given my specific concerns I have to approach it rather carefully. The way I’ve approached it is, again, more with a concern for low relief — what is in front of something else in a very narrow kind of space. When you say a “flat sculpture” — I think my paintings could be seen as a sculpture of a space about an inch thick, kind of like ants in an ant farm. Do they have ant farms in Italy?

GP: Yes…[laughs].

PH: Maybe there’s sculpture in that.

GP: Is your painting always what you expected at the beginning, or during the execution are there some emotions or some ideas or some weakness or something that would change the painting?

PH: I like to emphasize that both in the making of an individual painting and the movement from painting to painting my work is not at all programmatic. As mechanistic or repetitive as my work may seem, the changes in it nevertheless come from subjective reactions on my part rather than from a programmatic demand like “now I’ll make a green painting, and then I’ll make a blue one.” In this, I really part company with minimalism and programmatic art. It’s all very subjective; in general I extrapolate from that. Even though one is dealing with a rational, totalized world, the best way to understand that world is through one’s subjective reactions to it, rather than through objective, rational analysis. That to me is the great lesson of Foucault who was able to my mind, to teach us so much about what has happened in our culture but who went about it almost like James Joyce, in this kind of stream of consciousness way.

GP: You’ve discussed the intellectual content of your work, but I find it is also very emotional, because of your use of color.

PH: I wouldn’t separate the two, and I’ve always claimed that mine is a subjective, affective program. The word ‘emotional’ is a little strong for me because it implies too many traditional things, but my work is about subjective reactions. Even though the elements that I use don’t change too much from year to year, at different times the work can still have a very different emotional feeling. A year or two ago my work was very quiet and still and static and many of the colors were dark or almost monochromatic. But over the last year and a half somehow my emotional response in the work changed. I see the newer work as much more humoristic, or pop or — I like to use the word absurdist. Where the conduits are going or ending up or coming from is less clear and their purpose seems to be more obscure, more ambiguous.

Helena Kontova: You said that the prints are a kind of departure for the bigger work, or a kind of program for them…

PH: The research for this was all done a year and a half ago. We went to the Business Library of the New York Public Library and got out all the diagrams of computer stuff. I always get a little upset when people think that I’m making up the extreme things that I say are going on in our culture. I began to look at these diagrams and I found phrases like ‘collision circuit,’ ‘character generator,’ ‘final attribute circuit,’ ‘priority circuit,’ that were unselfconsciously describing the kind of universe I had claimed existed out there. So in a way these prints exist as footnotes, rather than as a program for the painting. Some of them are really hilarious. This actually is a diagram for a robotic factory, and here’s a robot station, with the attributes of the robot broken up into speech, vision, transport and arm manipulation. This other one is a flow chart divided into station, cell, factory, process controller, security, all the way up to corporate headquarters. These diagrams seem to so precisely describe the kind of organizational space that I am interested in that I think of them almost as a kind of evidence.

HK: So this is related to your recent work, these kind of diagrams…

PH: It didn’t formally inspire the recent work, it just is something that I’m interested in at the same time. The paintings involve trying to make a space that I find to be the dominant or representative space of our society. Some of the other projects that I get involved with seem to be about researching what the different aspects of that system are. The fact that these computer system diagrams correspond so closely to that space gives a specific example of how it operates out in the real world.

HK: Could you tell us a little bit of your story from the beginning? How did the first painting come to be, I mean the first, abstract, DayGlo painting, how did you develop this kind of idea?

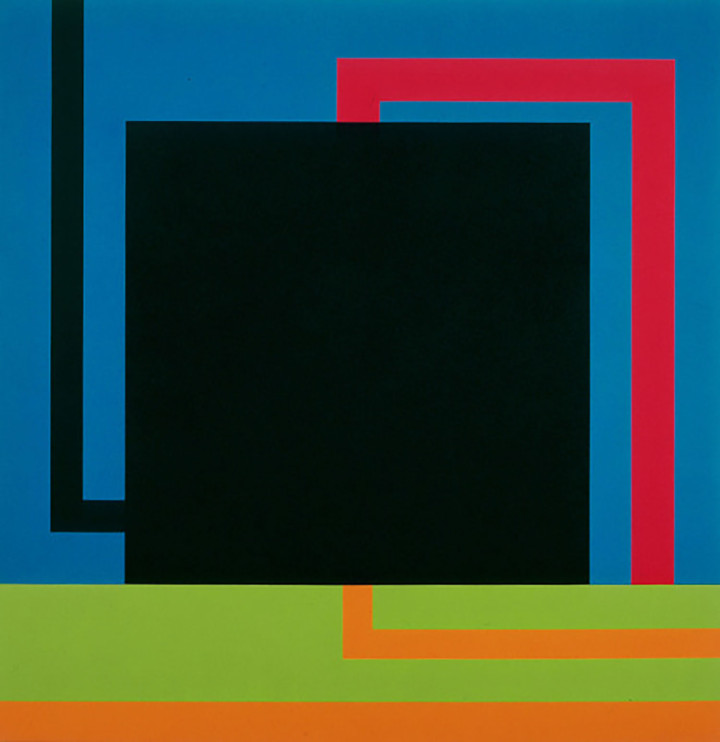

PH: Let me try to trace that carefully… I guess during the ’70s I was interested in the relationship between geometry and nature. Like many other artists I imagined that one could posit a connection between ideal geometric forms and an order that one might find in nature. Around 1980 I began to feel disillusioned with that kind of structuralist connection between idealist platonic form and the natural world. At that time I moved to New York and began to feel myself psychologically affected by the kind of totalized urban environment that one has in Manhattan where the phenomenon we call nature, for the most part, is excluded. I began to try to come to terms with that situation in my work. I wanted to start to work with what I thought was the quintessential idealist form, the square, which had both a general, intellectual history and a specific history within modernism. I wanted to say two things; first of all that geometry existed in real space, and that’s why I put Roll-a-tex on the square so it could become something architectural or something physical. Secondly, I wanted to make the square something no longer ideal, because I imagined it as a space of confinement, and so I put bars on it and it became a prison. Having started to look at geometry as confinement or segmentation, the next thing I began to think about was how movement was controlled in this kind of space and the kinds of connections that existed between these kinds of isolated spaces. I imagined that such connections would take place underground, the way telephone wires or electric wires in an urban environment travel below the ground. I began to think about hooking up the squares, which I began to call cells, with each other or with the outside through this image of an underground conduit. As I worked with that over a period of a couple of years I began to feel that it was quite a succinct way of expressing the space of our culture. I felt it was worth sticking with and worth continuing to explore over a period of time, to see what I would find out about the space and how I would react psychologically to it. But I also felt it was very important not to elaborate on that relationship unnecessarily, in other words not to make the cell into a house or into a micro-chip, or into anything too specific, because the whole basis of the system is that the model preceeds reality. Whether it’s a house or a car or an office or a hospital bed they all conform to the same model, so that the paintings could not really depict any specific application of the model but only the model itself.

GP: As a student, in your first experiences as an artist, were you always working just with geometric images?

PH: Not always, but to a large extent. For whatever reason, we think of geometry as rational form. But for certain people, myself among them, it has an unconscious strength or a strong unconscious meaning. Clearly I began to work with geometric form before I decided on this meaning for it. I think that I’m psychologically drawn to geometric form and that my development as an artist was to discover, to make conscious, what geometric form meant for me.

GP: I would like to know your opinion, as a convinced rationalist, about how successful artists like you or your friends deal with the enormous pressure from the market, the media, the explosion of prices, the requests by museums and private galleries and private collectors. How do you feel; how can you defend yourself, if you want to defend yourself; for instance your private space, your private life? Do you still have time to read, to spend with friends, or is your life programmed around work?

PH: Well, on a personal level it’s always difficult because of the demands both in terms of the outside world and the internal demands of one’s work. I think this has all developed more gradually than one thinks. I remember reading in the early ’70s that Richard Serra said he thought about his work 16 hours a day; you can’t think about work much more than that. Even then artists were busy going back and forth between the United States and Europe a lot. There’s no doubt that contemporary art is becoming more popular but I think it’s also been a gradual process since the ’60s. Its popularity is generally nice but it worries me in one sense, in that when something becomes very popular it tends to become diluted. As contemporary art finds such a wide audience around the world it troubles me that extreme kinds of work may be excluded. I always use the example of Vito Acconci’s Seed Bed, which is a very provocative piece. It’s very hard to imagine an artist being able to make a piece like Seed Bed today, and have it be at the center of a dialogue the way Acconci’s piece was in 1972, or whenever he made it.

GP: Who buys your paintings — collectors, dealers? Do you know who is buying your work, or are you just the producer? Do you control the life of your works?

PH: At first I did, for the first couple of years. But since I began to work with major international galleries they pretty much tell me what to do [laughs]. If one did it otherwise then that would have to become the subject of one’s work. To some extent my work is based on the idea there’s a possibility of a progressive bourgeoisie, that those with the funds to support culture will support something that will result in a higher level of consciousness about the social. Perhaps that’s a big ‘if’ but I think almost everyone in the art world is betting on that. Didn’t Marx say that the bourgeoisie was the only revolutionary class? There are different kinds of factions within the bourgeoisie and I think for the last century or so those involved in the support of contemporary art have tended to be the progressive bourgeoisie, so that’s what I’m hoping for.

HK: By ‘progressive bourgeoisie’ do you mean a necessarily leftist-oriented bourgeoisie?

PH: In the sense that the left might be identified with this effort to reveal the nature of conditions in the social, to make it conscious.

GP: Do you like to keep your works? Do you feel a kind of attachment to them, physically, or not?

PH: I keep a few of them but they’re so hard to take care of, so in a way I’d rather let someone else worry about them. But I like to collect other people’s work. You have to be very wealthy to take care of my paintings, I can’t manage it [laughs].