First and foremost, Paul Pfeiffer’s retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, “Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom,” is a rush. It is loud and big and colorful, and while those things can become crutches for work that is otherwise rather thin either conceptually or technically, in this case it feels appropriate. The majority of the work takes as its subject matter the spectacle of modern sports. I am skeptical of exhibitions which seek to transform the gallery into a set or experiential replica of another space. Often, these feel like cheap tricks, and they usually fail. By attempting to recreate in great detail a certain space, the here and now which gives a place its aura is lost in translation. Pfeiffer’s exhibition avoids this trap via a subtle distinction. He does not attempt to recreate the sporting event itself; instead he goes straight for the aura. The exhibition then asks us to consider the mechanics and intricacies of aura itself. Can it be separated, isolated, distilled from that phenomenon to which it is attached?

Pfeiffer’s two-channel video installation Three Figures in a Room (2015), the subject of which is a 2015 boxing match between Manny Pacquiao and Floyd Mayweather, provides insight. On one large screen, the televised footage of the fight is projected without the original audio. On the adjacent one, Pfeiffer has made a film depicting Foley artists recreating the audio from the fight. We watch as they shuffle like boxers on a small board and experiment with how to best recreate the sounds of boxing gloves hitting bare skin. Long portions of the film also show the small screen the Foley artists use to watch the fight they are recreating. While we see each drop of the boxers’ sweat in brilliant high definition, the Foley artists watch grainy, “poor images” to borrow from Hito Steyerl. She notes that “the poor image embodies the afterlife of many former masterpieces of cinema and video art.” Watching two versions of this event side by side, which originally cost $90 on pay-per-view (or $100 in HD), the viewer confronts pure alienation, “the conditions of existence,” as Steyerl describes it. Walter Benjamin might suggest that this confrontation with the artifice of spectacle destroys any remaining aura of the live event, but I am not so sure. The family watching next to me still recoiled in shock at the sight of a Mayweather jab landing squarely on Pacquiao’s jaw despite seeing the sound itself being manufactured. With that said, certain sounds — the fighters’ heavy breathing and the words exchanged as they circled the ring — were not reproduced. In other words, those sounds which, in their vitality, do not make for such neat mechanical reproduction.

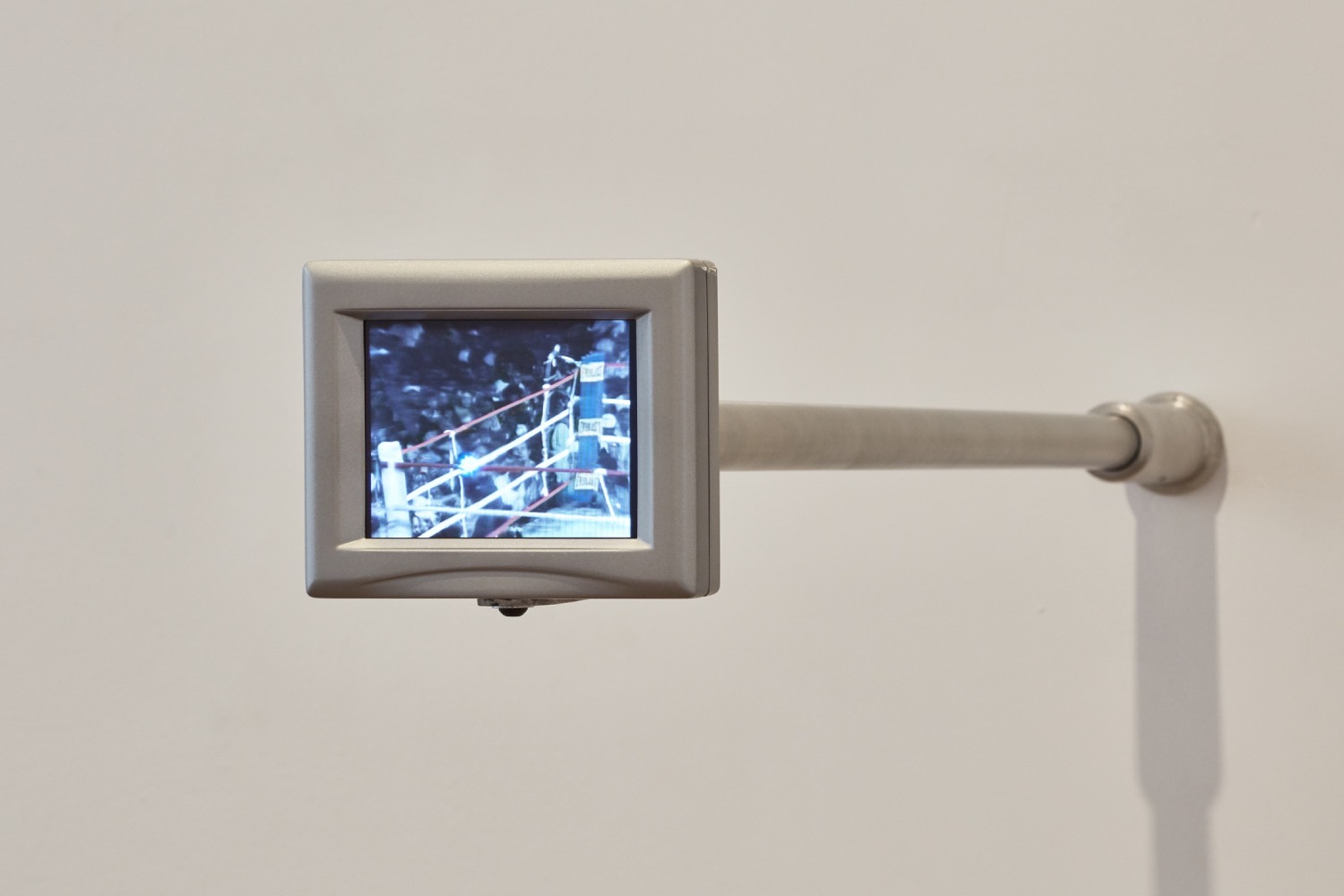

As opposed to the intensity of the visual spectacle in the Pacquiao-Mayweather bout, Pfeiffer asks us, in perhaps the exhibition’s most unsettling work, to consider the power of a purely sonic aura. Situated in a cavernous, bare gallery, the work is comprised primarily of sound, specifically that of a roaring crowd approaching a fever pitch. The rumble of the crowd is so overwhelming it is processed more somatically than aurally. One doesn’t just hear the roar, one feels it, is absorbed into it. Without a clear source or visual accompaniment, the roar is untethered, a disorienting experience. Pfeiffer does provide some visual context, though, in the form of a screen no larger than a few square inches on the center of the back wall showing black-and-white footage of the soccer match the crowd was presumably watching as well. The relative weight given to the sonic and visual elements of the piece makes clear that aura is aural.

It would be hard not to mention Pfeiffer’s 2008 sculptural achievement Vitruvian Figure, a hypothetical model stadium capable of seating one million spectators. Working with a team of skilled laborers based in the Philippines, the replica is intricately built, each seat individually crafted. The work’s creation asks us once again to confront quite literally the alienated labor used to construct monumental stadiums, whether at MOCA or the World Cup. Notably though, we are asked to take this perspective from the position of a spectator. Our view of the stadium is not from the field looking up but from the top deck, the nosebleeds. By foregrounding the labor necessary to sustain spectacle, Pfeiffer pierces the illusion of it while simultaneously pushing us to become part of it. This is both thrilling and sinister.