Originally published in Flash Art International no. 200, May – June 1998.

When the paintings of John Currin were first exhibited at Andrea Rosen in New York in 1990, the audience of the day was, according to Andrea Rosen, “disgusted and perplexed,” except for what amounted to “a small, secret society of admirers.”

I was not yet in New York, nor aware of the work, but am convinced that had I been, I would have been a confirmed member of that society. I was still a student in London, a baby artist still the virgin of a painting dilemma, though certainly feeling the ignominy of being a figurative painter the year after “Freeze” [London Port Authority building, Surrey Docks, London’s Docklands, July 1988].

If one was painting then it was assumed that it was out of ignorance or from a stubborn refusal to notice that the world had changed.

Particularly perverse was the desire to depict human beings, let alone wanting to do so using oil paint on canvas, and if one could not let go of these highly suspect compulsions, then they must be employed only with tongue thrust deeply in cheek.

I was ashamed of my pleasure in painting, my predilection for emotionally charged subjects, and for my love of dead painters. I eventually gave up painting; unable to come up with a good reason to be doing it, or to justify it, I seized up. All the painters included in this article agree that it was a difficult time to be painting. Currin says, “… the art world was so guilty and embarrassed after neo-expressionism… painting was a laughing stock. It was viewed with great suspicion, for being too intoxicating and religious…” Now, at last, the art audience, perhaps hungry for authentic experience, appears ready to move on, to stop treating painting as a whipping post.

This is an intoxicating time to be painting, and New York an exhilarating and sympathetic climate; the mood is generous and open and eclectic. It is the first time that I have felt an affinity with work being made by artists of my generation: John Currin, Giles Lyon, Damian Loeb, Michael Bevilacqua, Matthew Ritchie, Rita Ackermann, Christian Schumann, to name just a few.

1997 double show “Project Painting” (at Basilico Fine Arts and at Lehmann Maupin), a survey of painting being done now, mostly in New York, was a perfect illustration of how painting is alive and energized, looking fresh and fabulous. That it should be a task to select just a few painters to discuss is amazing. Peter Schjeldahl, in his Village Voice review of Rita Ackermann’s recent show at Andrea Rosen, appeared to have an epiphany, and made the following statement, which could be applied to many young painters here, “Irony is out. Humor is in. Sincerity is a given and no big deal.”

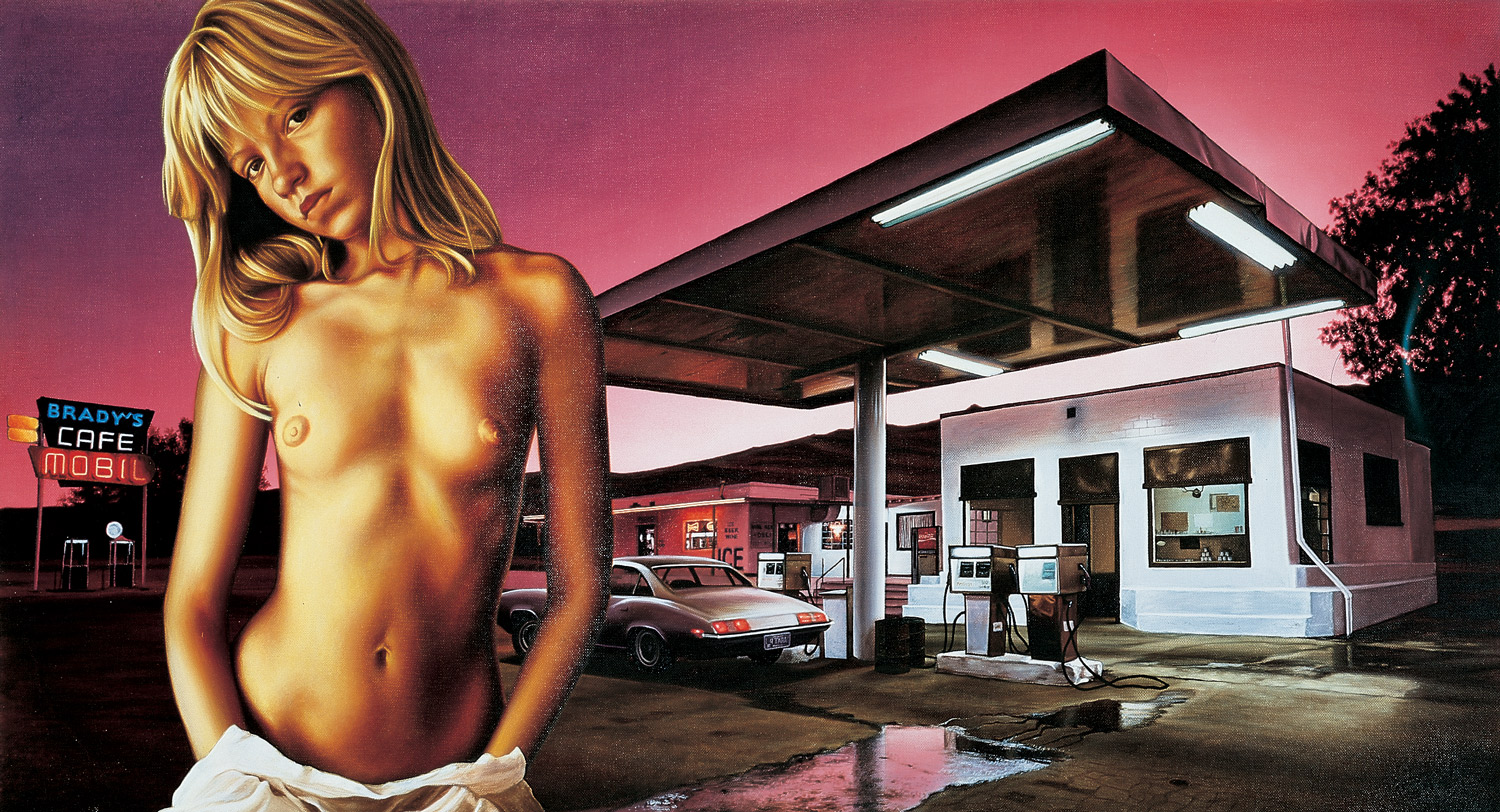

It’s also unapologetic. Personal. Hedonistic and sexy. Embracing artifice; creating fantasy documentaries where anything can happen. Absolutely in the discipline but not nostalgic. To quote Matthew Ritchie on the subject of another young figurative painter who is enjoying a lot of attention, and apply his words to all of us, “… the work of Elizabeth Peyton implies that it is possible to fall in love again. It might be risky, but it’s possible.” Ritchie sees a generosity, a questioning, and a sense of no closure as characteristic of new painting. The references in all of our work are wide ranging, but it’s not about making references; it’s not appropriation. “Appropriation is a dead term,” says Damian Loeb. “We’re not plundering. We’ve been force-fed. We’re not sampling — we’re digesting.” Giles Lyon agrees, calling appropriation “dead end and nihilistic.” Ritchie says, “… in the ’80s artists were playing an end game. Now there seem to be any number of viable endings, or no ending.”

One advantage that I think we have in terms of timing is the distance from any major movement in painting. Ritchie asks, “Who casts the longest shadow?” and suggests that we are the first generation to have no titanic figures casting their shadow; what we have to reckon with in terms of the recent past is the remains of bridges burned in the ’80s.

The death of De Kooning may have something to do with the fact that his influence is more visible in current painting than at any other time. The death of Bacon has made it easier (for me) to make paintings which use the only subjects worth painting — birth, copulation and death, of course. And perhaps the fact that Bacon died just a few years ago, and that Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff are still at it in London, is the reason why it is harder to be a painter there. As a painterly painter of figures, one does feel in the shadow of a recent muddy realism; the worm of Bacon’s legacy.

This is not to say that there has been no good painting in the States in recent years (there was always the hard core, such as Jasper Johns, Chuck Close, Alex Katz, and Terry Winters, who kept the game alive), but Abstract Expressionism, Pop and Minimalism seem far away, and most of the painting of the ’80s is so foreign in terms of sensibility that it is easy to almost forget all about it.

I don’t think that any of the young painters here see themselves as part of a movement, but there is a shared sense of surprise, because in our lifetime painting has been so very sick, and even the practitioners were not expecting such a healthy end to this century. Although there are vast differences between the artists pictured here, you could roughly divide us in terms of the way in which we approach pictorial space.

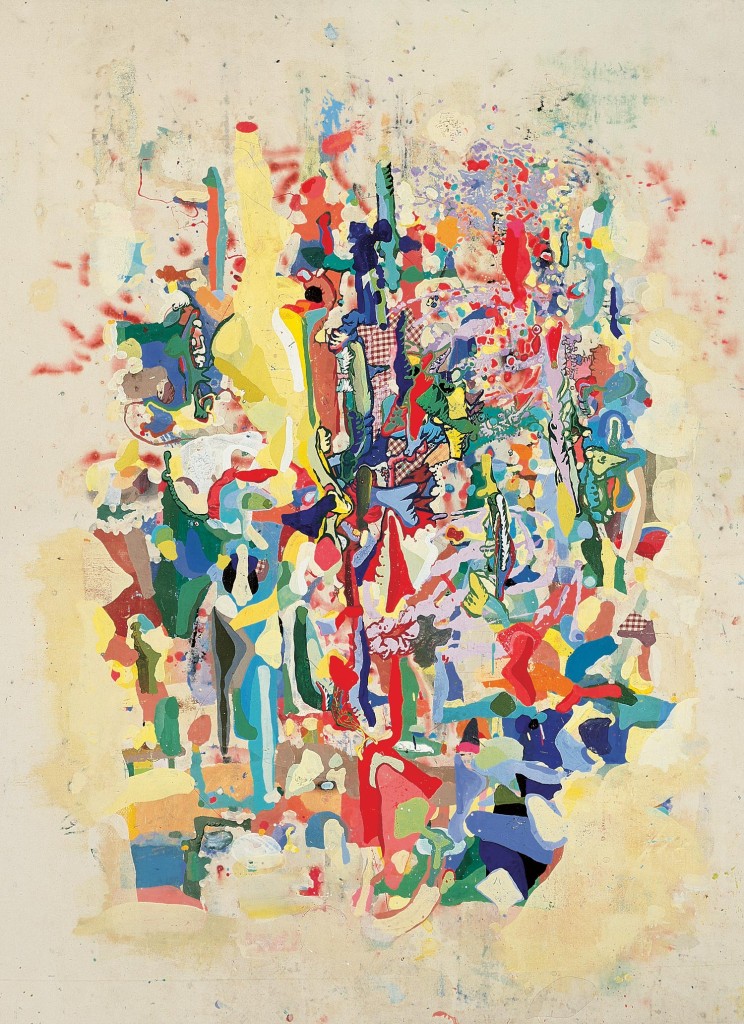

Lyon, Ritchie and I draw on the spaces opened by Abstract Expressionism as well as that of Baroque painting; Currin and Loeb do not. Bevilacqua is on his own, and I am drawn to him for his beautiful colors, clean and bright, and for the obvious pleasure he takes in making the pictures. In the press release for his show at Jessica Fredericks in 1997, was a quote that could be describing all of us, “… I am taking what I learned in high school art class and bringing it to another level.” The lack of shame in painting extends to the exploitation of natural skill. It is simply about believing that if you use a language well, you will be more easily understood. Loeb says that he is not a painter, “I just use painting to say what I have to say, because I can paint. It’s the best way for me to get things across.” I asked Currin, Loeb, Lyon, and Ritchie about the art that has meant the most to them. Both Lyon and Ritchie name Philip Guston as probably the strongest 20th century influence. Lyon says, “I don’t look at many contemporary artists with the same kind of wide eyed astonishment as I do at Guston,” though he describes Terry Winters as “compelling… he’s really going to town, and there always seems to be a purpose.” Ritchie credits Guston as “… head and shoulders above the rest as an influence; he’s truthful, angry, funny… they’re so beautifully painted, so sad. He set the tone. People like Winters and Dunham kept the whole thing going… Winters seems to be at the dark heart of the whole enterprise — so pure it almost says ‘convert or leave.’ It’s genuinely open to change and keeps evolving. It’s a bit like listening to somebody talking about God — at length.”

Currin says that he never felt much for Guston, though when at school made wannabe De Koonings; Loeb has little time for many artists of this century, but mentions Degas and Ingres, and Bacon. (Everybody mentioned Bacon). He says, “I love Bacon. You saw Bacon as a kid and he scared the shit out of you. He was like a monster that you couldn’t discern and you couldn’t dismiss. I saw De Kooning and it meant nothing to me. I don’t know how anyone who doesn’t know about art can relate to that. Critics always write as if it’s understood that art is a dialogue with other art. It’s like an overbred dog.”

Currin’s art is in dialogue with other art, but it extends far beyond that. I envy his precision, his ability to make a singular, specific image. He mentions the films of Fassbinder; the use of slowness and the risk of boredom, one ground and one figure, with “make-up too loud for the dullness of the situation.” He describes photography as being “climax and consummation all at once,” making it the one night stand to painting’s long engagement, or even marriage, and extends the metaphor when he calls my paintings “promiscuous.” I see both lust and love in his pictures, tender vignettes that conjure ghosts of Fragonard, Van Gogh, and the Baby Doll Lounge. (When was the last time that a contemporary painting made you think of Van Gogh?) Currin’s comments on the work of other artists are particularly revealing about his own. Velazquez’s “Rokeby Venus” has a “slow warmth” and is like “touching the flesh of the beloved.” Renoir is “Unbelievable. Shallow and deep. Clichéd and amazing.” The Leonardo’s Portrait of Ginevra de Benci in Washington is “so beautiful you could look at it forever. You can see it all at once but never possess it. But the beauty of it is consolation for the fact that you can’t possess it.”

Currin is shallow and deep. Authentic and fake. He’s about looking so hard at something that it becomes inflated by the gaze. He refutes the word “gaze,” but talks of a “consuming, greedy suckling of appearance.”

It’s about desire and possession, and the inability to possess, and the force of the desire, and the expression of that greedy suckling of appearance, and love, and romance, and how to make it more real and more fake, and ever more intimate, while knowing that it will never be close enough.