Catherine Wood: I’m interested in your use of architectural forms as sculptural obstructions within the gallery space — thinking of your MA show at Goldsmiths, your piece for the ICA’s show “London in Six Easy Steps,” which I co-curated with Jens Hoffmann in 2005, or Magnificent Triumphal Arch in Pompeian Colours (2010) in the Hayward Gallery’s show “Move: Choreographing You.” I like the way you graft these obstructive forms as ‘scenography’ (connoting a bigger picture) with real space and the physical experience of the visitor, so that they create ‘eddies’ in the pedestrian passage through a space. Can you say something about that impulse, and about how it relates to your engagement with contemporary ideas of ‘space’, choreography and ‘participation’?

Pablo Bronstein: Architecture is able to choreograph in an obvious and direct way — you can walk through here, but you can’t walk through there. You can climb up here, you can leave through here. Then it choreographs in a slightly more subtle way: you first walk here, then you will walk here, then you will walk through here more quickly, then you will linger here, and then you will leave. Architecture choreographs our thoughts through ornament: you will buy from me, you will fear me you will remember me you won’t see me. Then it can also say: I remind you of Ancient Rome, I make you think of the ’60s, I make you feel wealthy — and this can even make us wealthy or poor. We are complicit with and see ourselves through architecture, and so some of these impulses are dramatized by my role as an artist creating these lumps. In the recent work for the Hayward Gallery the dancer addresses the temporary architectural sculpture in the shape of a triumphal arch. Firstly the dancer changes the way she moves when near the arch — so from pedestrian movement, to another sort of language around the arch, and back to pedestrian movement. Then by talking to us — to the other viewers of the arch in the space — about the arch but always through the arch and therefore also to the arch. It’s as if the dancer / viewer is caught in the glare of the ornamental architecture.

CW: How do you connect these inserts into the ‘real’ (albeit artificially bounded white cube) space of the gallery with the pieces you’ve made to be viewed as theatrical tableaux, for example the full-blown theater piece in Turin, or the Shakespearean Pot Pourri (2010) in the garden at Tate Britain? There’s an intriguing push and pull between full immersion or identification with historical material, and exposure of its artifice in your work.

PB: Even with full-blown immersion there are protests within it. During the recent theater pieces, such as at Tate or in Turin, the predominant sprezzatura body language of the dancers collapses into pedestrian movement on stage, thereby throwing off the coherence of the language. This also signifies to the audience that the dancers are not working at that point, which is an illusion. One other way in which these more immersed pieces twist is that the frame for the work is somehow larger and includes the audience within it. In Turin in 2009 the work was conceived as a ‘theater work’ for a traditional city theater on Saturday night, hence the choice of Jean Racine’s Phèdre (1677) as a play, and the classical music and the traditional format. The truly fuller immersions are the ones that lie outside the safely constructed and recognized areas demarcated for theatricality.

CW: Your piece at the Chisenhale Gallery was, uncharacteristically, made entirely from municipal stacking chairs, but it created an extraordinary effect as a maze within the space, animated by the crowd of visitors in a part choreographic, part aggressive way: people sat neatly in rows facing each other in some sections, appearing as though sitting at the side of an 18th-century ball; in other parts they walked, frustrated, back and forth in order to be able to get towards someone they wanted to talk to, or to get out. Similarly, your piece Plaza Minuet (2006) performed in London and New York has created interventions in busy public spaces that have created diversions within the pedestrian activity going on there. How do you see the function / aesthetic / politics of choreography as it relates to the world at large, full of moving bodies?

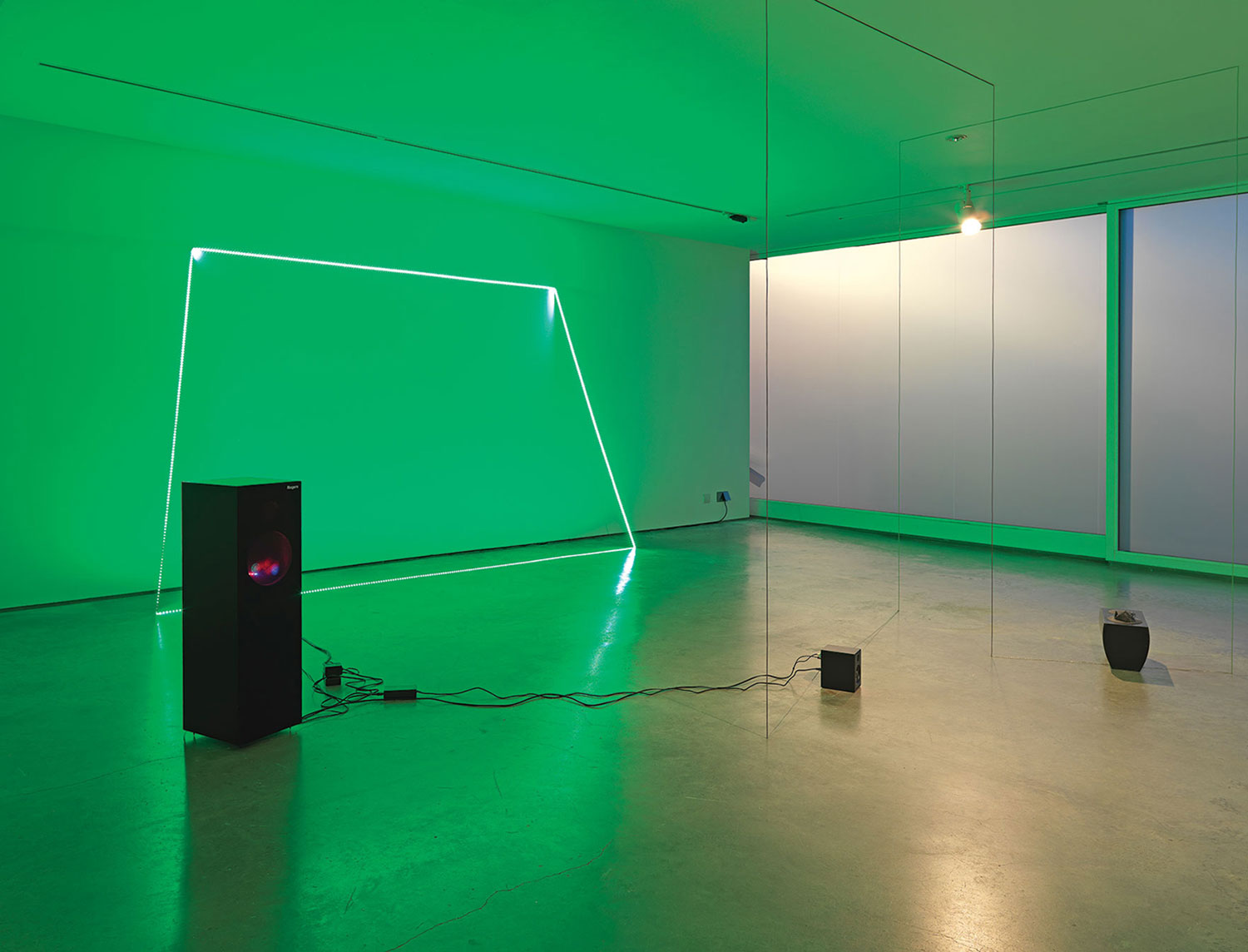

PB: My choreography is a sort of scramble for land around an initial abstract idea. If I am given a space to fill, there is an imaginary dot in the middle, and from that the choreography or installation germinates in an attempt to negotiate between this center point and the surrounding world. In my first pieces this space generated what was called a void, or was demarcated as an empty space in which an abstracted ideal citizen or figure would exist and move in a system of movement parallel to our own. This world created was probably a queer world, in which genderless action occurred, removed from the idea of work. This is so at the Tate Triennial Plaza Minuet and the more aggressively situated Plaza Minuet for Performa07. Later on this changes, and becomes both placed within a dramatic or dance tradition, or it is commented upon, in the space of a lecture theater — such as Intermezzo (2010) at Tate Modern. The politics of this initial desire to ornament the void is one of resistance to the institution. To re-make the surrounding space into one powerless in the face of the artwork, one in which the space of the institution has been pushed to the sides — such as the large area taken over by us in corporate lobbies for Performa07, forcing people into the corners — or such as the installation at the ICA, whose use of gallery-going politeness forced people against the walls.

CW: I’m intrigued by the frequent “performance of authority” within your work, whether you are playing the choreographer directing your dancers, performing as lecturer in Intermezzo, publishing books, making your incredibly competent drawings in historical style, or giving an architectural tour of London. Could you say something about that desire?

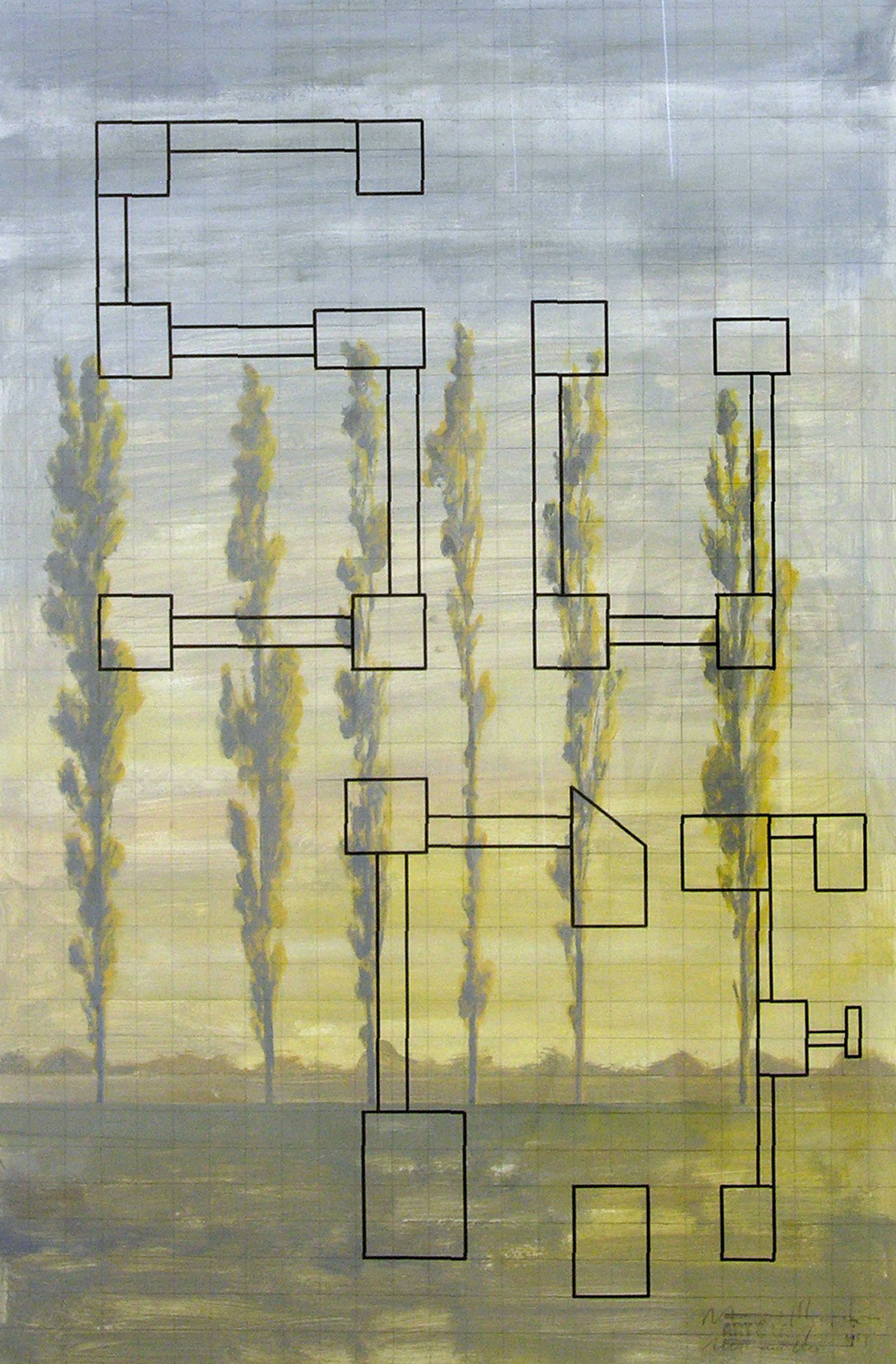

PB: The drawings are by a despotic architect, or they are in the service of an imaginary despot, be it an individual or a group. But drawing elsewhere is important, because the command or authority seems to me to draw a choreographic line in space. Or rather two points are given and I draw the line: someone points a finger and something else happens which is not directly in physical contact with the end of the finger. The political speech is one such rehearsed performance of power. Initially I have to ignore the world in its complexities and demographics when I choreograph the space — rather the work is a role-playing that I get carried away with — “I want a walkway here… I want people to sit there… I want people to raise their legs now…” I want people to watch me do this, and I want people to watch other people and/or themselves comply, and simultaneously I want to catch a glimpse of something beyond this. I love that moment in the theater when an extremely conventional scene is repeated to an audience that knows it already, and it is still found to be beautiful. Although, being partly Latin, I am relatively familiar with bullshitting for pleasure, in the style of Borges or Umberto Eco.

CW: You and I are both fans of Jack Smith. Could you say something about how his work influenced your own work? I am thinking not only of your work but also of your flat which you’ve transformed into something of a Georgian idyll through your collection of antiques and treatment of the architectural details, the moldings and cornices and so on?

PB: Jack Smith is interested in normality. In particular gender roles, and how camp can subvert these. His apartment, which he turned into a plaster grotto, became an example of how not to live according to the prescribed laws. There is an element of wanting to demonstrate the constructedness of the surrounding system — be it the formal white of the gallery, or the pedestrian ‘normality’ of behavior. I try to use sprezzatura to directly comment on ‘normal’ and gendered body language, as the system was in general and very widespread use as a behavioral and etiquette alphabet in the past, and still lurks as a subversive force in pockets. Another thing is that inside Jack Smith’s universe, the artwork and films are some sort of excess product or condensed excretion of his way of life. Or even of his interior decoration scheme. So I sense in him that the making of an artwork, like me, is slightly by chance, or arbitrary. Also, what Jack Smith does with film, making it into ‘film,’ the playing at ‘creating’ or directing, I do with drawing or dance, making it perform as object on the wall, or the dance into ‘dance.’ Jack Smith plays a deliberately secondary or minor role in the New York art world — but one that left him freer to explore ideas without having to compromise in favor of larger commercial production. In that sense he is my hero. But what draws me to him most is his antiquarianism — his fustiness, which can be mistaken for grime. The objects (films) are obsessed with history, but they are also about his role as an antiquarian. He rescues actress Maria Montez from obscurity, but keeps her in the shadows and mystifies her, or fetishizes her obscurity. I have a similar response to historical subject matter.

CW: There’s an apparent contradiction between elements of flagrant triviality — decoration, extravagance — and a gesturing towards politics in your work. Or is it a contradiction?

PB: With decoration, interior design, and so on, it is the arbitrary tyranny of the creator that I am interested in — the whim becoming visible, of authorship per se. Decorating, something without an easily approved raison d’être, renders this more visible. For example the sofa that has to be yellow. The walls that would be too bare without the cornice, and so on.

CW: Your shows at Herald St have taken significant steps towards video installation, which is the one time that your work becomes situated firmly in the present (from a technological point of view at least). How do you reconcile the mediation of live presence through film and video with the immersion in the past that you talk about? How do you think about the relationship between the dancers on film (often projected at approximately life size) and the viewers in the space?

PB: Both films at Herald St use un-advanced video technology. There are slight manipulations of grain, for example the film Origin of Sprezzatura (2010) uses a slightly older video quality and light contrast, so that it reminds us of television shows from the ’80s such as Blackadder II, which was partly the inspiration. The film Walker (2010) was lit as if it were a Robert Palmer video. The films are all one long take that has been looped. So, real-time as far as the performance is concerned — we are still tying the videos nominally to the idea of dance documentation. The dancer in Origin of Sprezzatura is projected on the base of the wall, and is slightly smaller than the average person. We look down on him. The Walker dancer is huge, and is in a neutral black space (it is projected in a pitch black room), so the same space as the viewer. She is bigger, potentially threatening, but more than anything a huge piece of meat.

CW: What are you working on now? How is your world evolving? Will you continue to work across so many formats (theater, publishing, sculpture, choreography)?

PB: I’m directing a play for Dramaten [the Royal Dramatic Theatre] in Stockholm called Celebrated Deaths from European Literature. We are in rehearsals right now and it is the most immersed thing I’ve done so far. I don’t like contemporary theater very much, but I am interested in being in an alien context, so it has to appeal at least partly to the theater audience. It will be a role-call of dramatic convention of tragic endings. I’m working on a book for Xn éditions in France that will initially be about the development of early ballet and sprezzatura, though it will encompass a history of the late renaissance, the origins of the proscenium, drawing and painting, as well as choreography. Through looking at a painter called Antoine Caron we will hypothesize a series of proto ballets staged for the French court at the end of the 16th century. It will be partly researched and partly intuitive, and the majority of it will comprise a series of new choreographies laid down as diagrams and in photographs. I am due to make a series of survey drawings of the British Embassy in Paris, which will use misread measurements and be in a provincial style. I also want to make a small ballet film about the birth of the modern sewage system, so I need to convince people that it is a good idea.