Olivia Erlanger’s exhibition “If Today Were Tomorrow” starts in space. Space as in vantage point. Space as in site, both fixed and rangy. Influenced by Lydia Kallipoliti’s The Architecture of Closed Worlds, Or, What Is the Power of Shit? (2018), Erlanger traffics in spaces that contain themselves — garages, intergalactic capsules, highways — yet hold the potential for something more.

Each of the four exhibition’s sections, or “zones,” takes advantage of CAMH’s subterranean Nina and Michael Zilkha Gallery to zero in on enclosed units spanning from suburban homes to dioramas to plaster planets that are at once comforting and disconcerting. A closed system offers a reliable repetition. Its everyday use provides an assumed relationality that guarantees return, neither optimistic nor austere. Erlanger’s commissioned installation and sculpture pieces directly respond to Houston, the self-proclaimed energy capital of the country. Erlanger circles, as CAMH curator Patricia Restrepo said, “the myths and the symbols that undergird American celebration of home ownership and suburbia.”

Walking into Erlanger’s first zone, film and installation project Appliance (2022), feels like entering a parents’ basement, a liminal space both void of and filled with identity. A couch, table, and chairs point toward a screen where Appliance plays on loop. Described as an enchanted object story, the film’s protagonist, Sophie, wrestles with the uncanny intrusion of her household appliances.

Erlanger extends the architecture metaphor of “the home is a body”: “If the home is a body, then the body is an appliance,” Erlanger insists. In this world, it isn’t climate change or political upheaval that threatens humans, it’s fizzing electrical sockets and open walls, the intrusion of media soliloquies on the radio, blenders and coffee makers unboxing themselves of their own accord. Sophie’s figure fades into the background of a transitioning domestic space. She watches TV while scrolling on her phone amid drop clothes and plastic covers.

There’s a Narnia quality to the idea of enchanted domestic spaces, a child-like power to assign wonder to the mundane. Yet this is too easy a summary. Appliance plays with the genres of body horror and speculative fiction to belay a sense of dread. The wound-like hole in the floor, made by a handyman as Sophie sleeps, becomes a mystical portal, a threshold, and a threat; as viewers, we’re waiting for the ways in which Sophie will fall into it. This dread is punctuated by surges of ominous music, comprised from twenty household appliances.

A closed unit is a structuring device for living that soon will extend past the home to influence how we survive globally and galactically. “Sprawl just keeps shaping the planet,” Erlanger says during an exhibition preview, standing between her two planets. The plaster surface of the planets, Antimeridian (2024) and Prime meridian (2024), serves as a skin for the suburban grid underneath, which is based on Northeastern US Highway 95. This hidden infrastructure accentuates how the body moves through a city, toward and away from its epicenter. It speaks to a world in which these circuits from city and suburb function in slower and slower rotations, where we no longer have corner stores and high streets, where our needs can be bought in bulk.

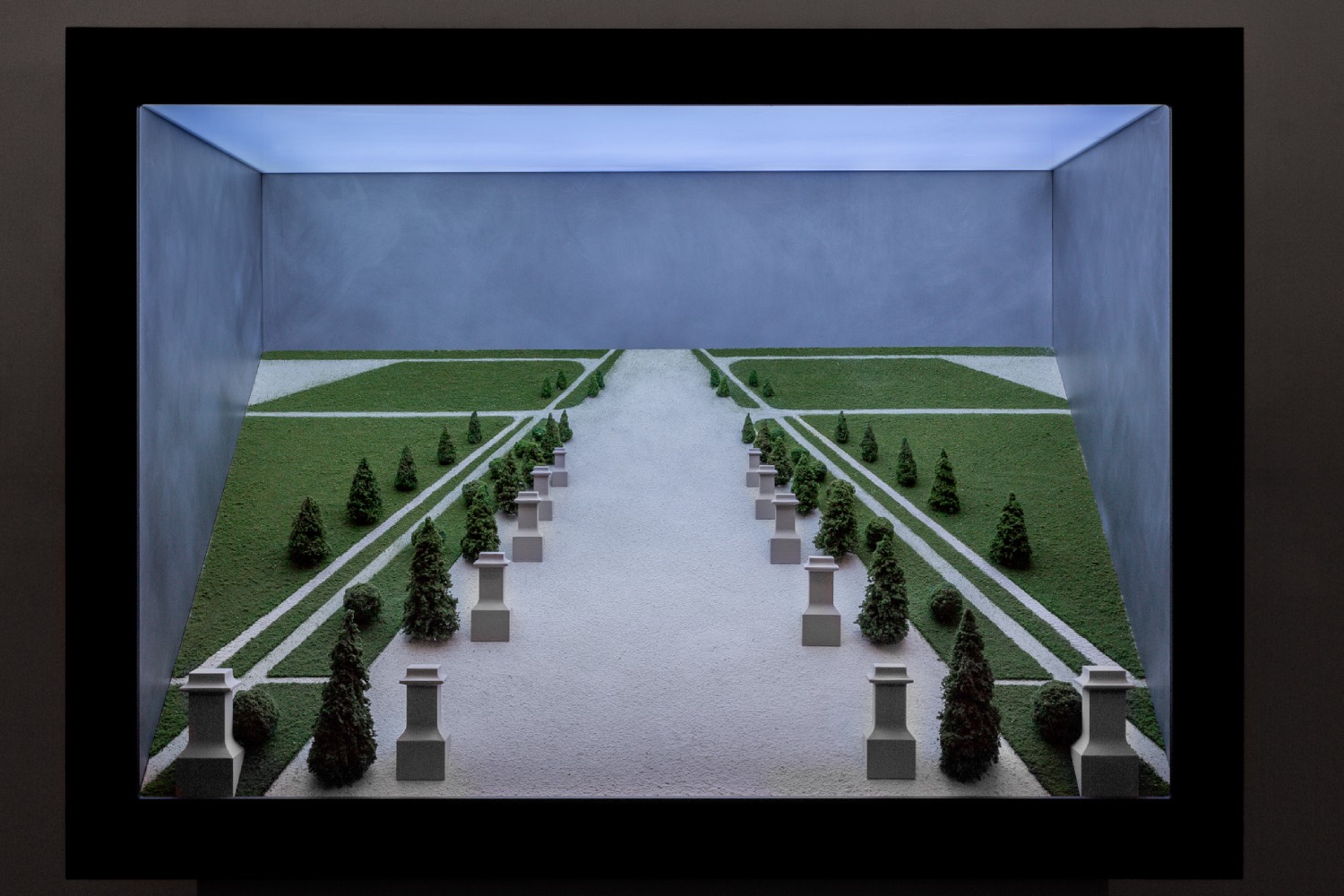

Erlanger’s diorama zone — cubic scenes of other worlds that feature the fragile treetops of a manicured winter park (Blue Sky, 2024), an emerald green speculative city-scape (Green Sky, 2024), and Dune-esque mounds doused in orange and yellow light — present the suburbs as, to quote theorist Lauren Berlant, a “convoluted apostrophe,” a failed attempt at plurality that leads to a barren yet wondrous singularity. These delicate boxes riff on the museum vernacular of display and carry with them the shadow of collective loss, the quiet after atrocity. What Erlanger captures here is not quite apocalypse. More, it’s the empty spaces we acclimate to after loss. Erlanger’s minatures drop the fantasy of repair, presenting life within rupture, the slowing of a human relational circuit. It’s worth noting that although playing with the institutional formalities of a museum, the diorama displays have no glass, indicating a porosity between this preserved, hushed, thingified world and us the viewers. It asks us to bring objects into our orbit of relationality and care.

The last zone is Eros (when night was last dark) (2024), a smattering of aluminum arrows placed across the austere stairs of the Nina and Michael Zilkha Gallery, aligned with the constellations of Houston’s sky on January 29, 1880, the day before Thomas Edison received the patent for the lightbulb.

Erlanger’s impending tomorrows are hopeful, but far from Utopian. Rather than represent the suburbs as vapid, tasteless arenas, the exhibition presents them as a lattice work of loneliness and wonder, something to complicate rather than bore.