The preternaturally gifted artist, musician, model and actress Kaya Wilkins — known in the creative industry as Okay Kaya — grew up in Nesoddtangen on the Oslo Fjord, and her visceral connection to water has never abandoned her, returning in multiple forms in her lyrics.

“She’s mixed in with / The Aegean sea / Sprung out and struck a pose / Why couldn’t I be Aphrodite / Venus / Sexy lovely God?” she says in “Origin Story (feat. Aerial East)” a track from her latest album, SAP (2022) — entirely written, performed, engineered, and produced by Wilkins with guest appearances by many collaborators — released last November via her record label Jagjaguwar.

Even if her identity as a creative is hard to pin down, her creations are always assuredly centered and totally in focus. Even her stage name is in its own way polysemic; “okay” can mean many things, with as many nuances as her image as it constantly evolves across different media platforms. Although Wilkins has lent her body to fashion, modeling for brands such as Balenciaga, Off-White, Calvin Klein, Marc Jacobs, among others — or played a teenage girl in love with her classmate in the queer psychosexual thriller Thelma (2017) — her main practice is now focused as artist and musician. She has performed with King Krule or Taja Cheek of L’Rain as well as others and collaborated with artists including Anne Imhof, Austin Lee, Ryan McGinley, Nan Goldin, and Dan Jackson. In the following conversation with Isabelia Herrera, the artist addresses her practice in all its truth, melancholy, and irreverence.

Isabelia Herrera: Your visual art has been in a number of solo and group exhibitions over the last two years. Why focus on that medium instead of music?

Okay Kaya: No matter what I do, an idea starts in my head and then I find whatever medium that is suitable. It’s just like, “This is a picture or this is a sound.” I don’t think about it too much. I do think everything is play in a really simple way for me a lot of the time. So like, “Oh, it could be an installation that has this theme.” Then I will write a song that has a similar theme the year after, but it will make sense in hindsight for me.

IH: Do you feel like one medium influences the other?

OK: Possibly more spaces. In sound, you put something out of nothing and then it creates space around that. But with being able to show other work, that’s more visual, putting something into a frame or a space that already has a feeling to it.

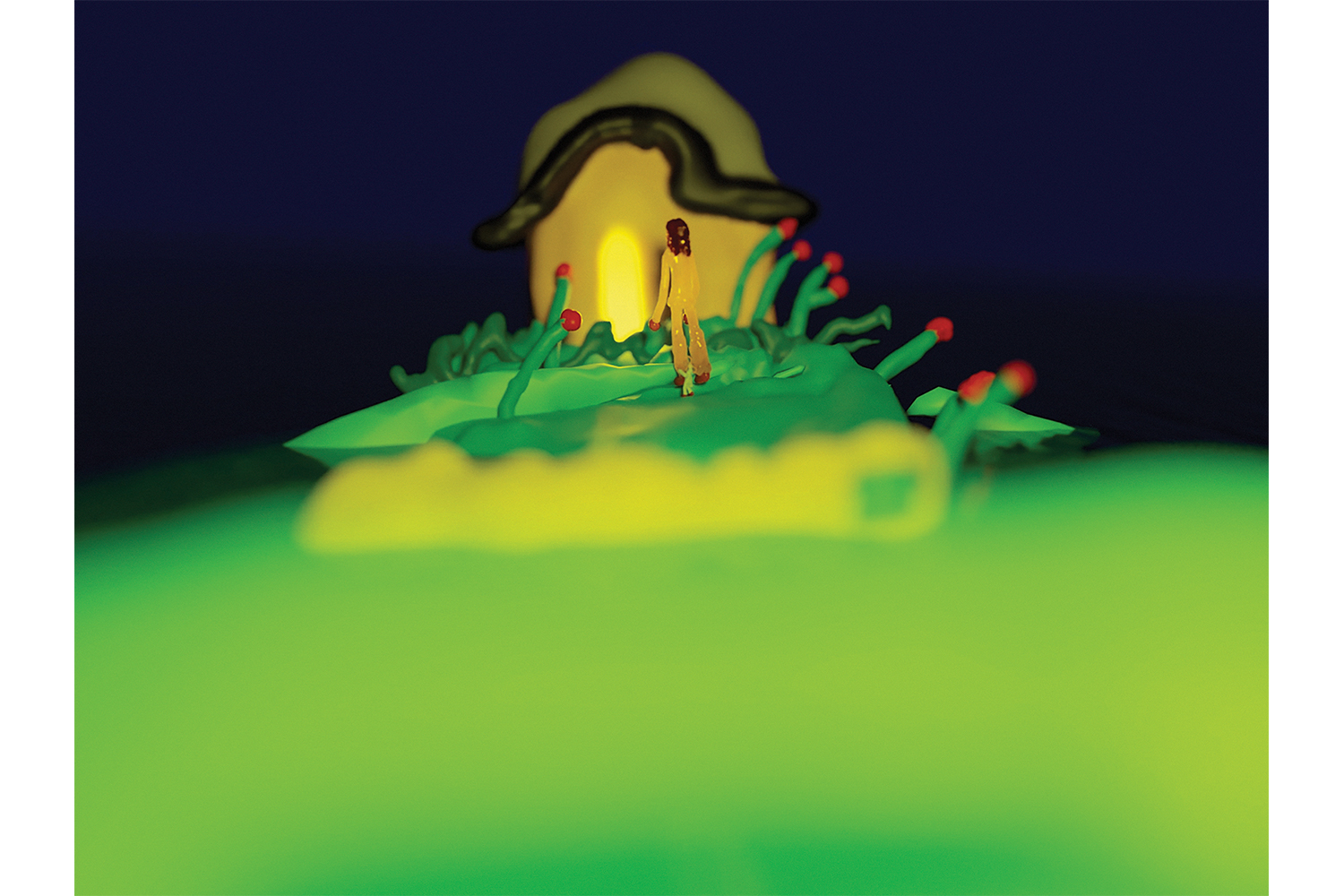

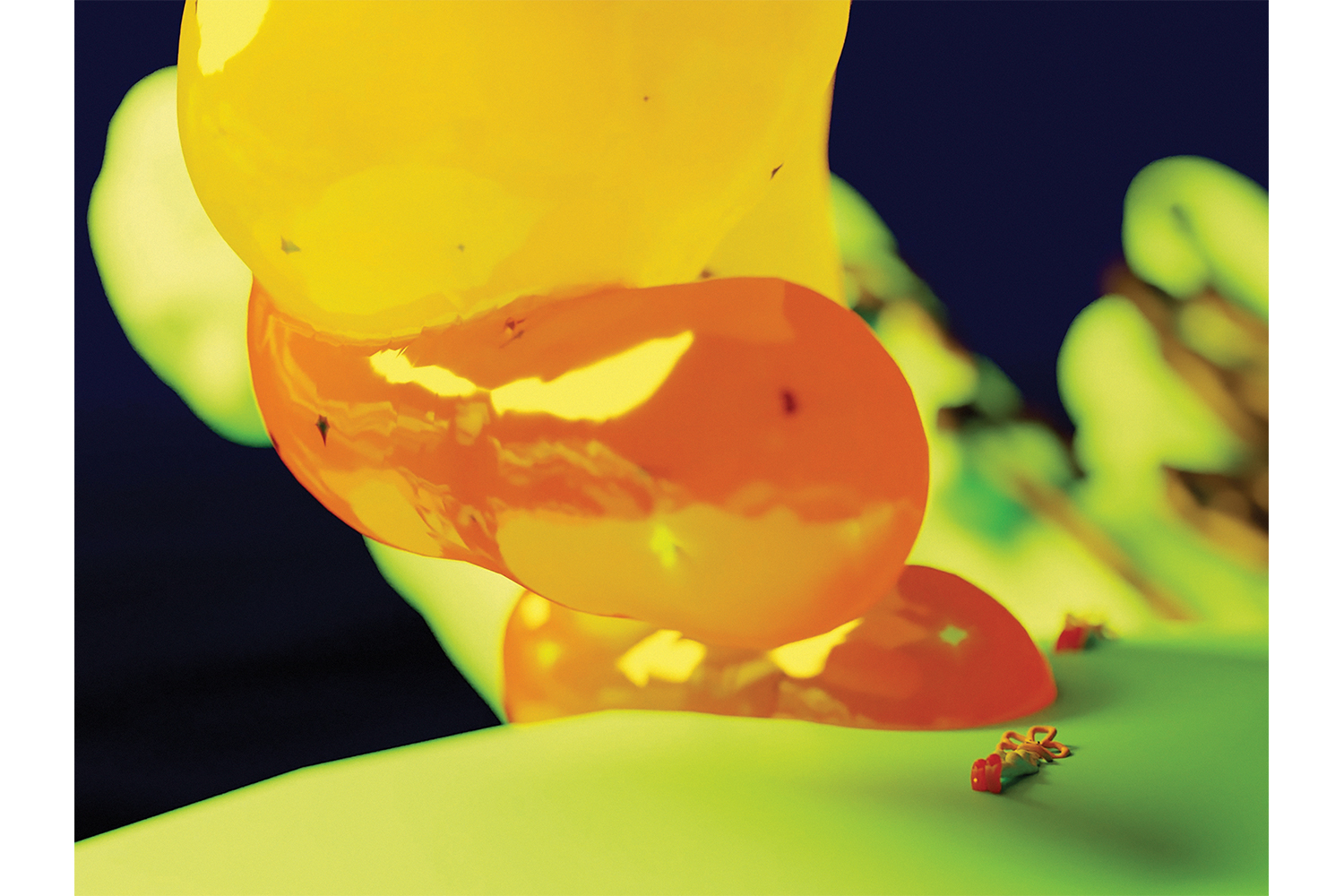

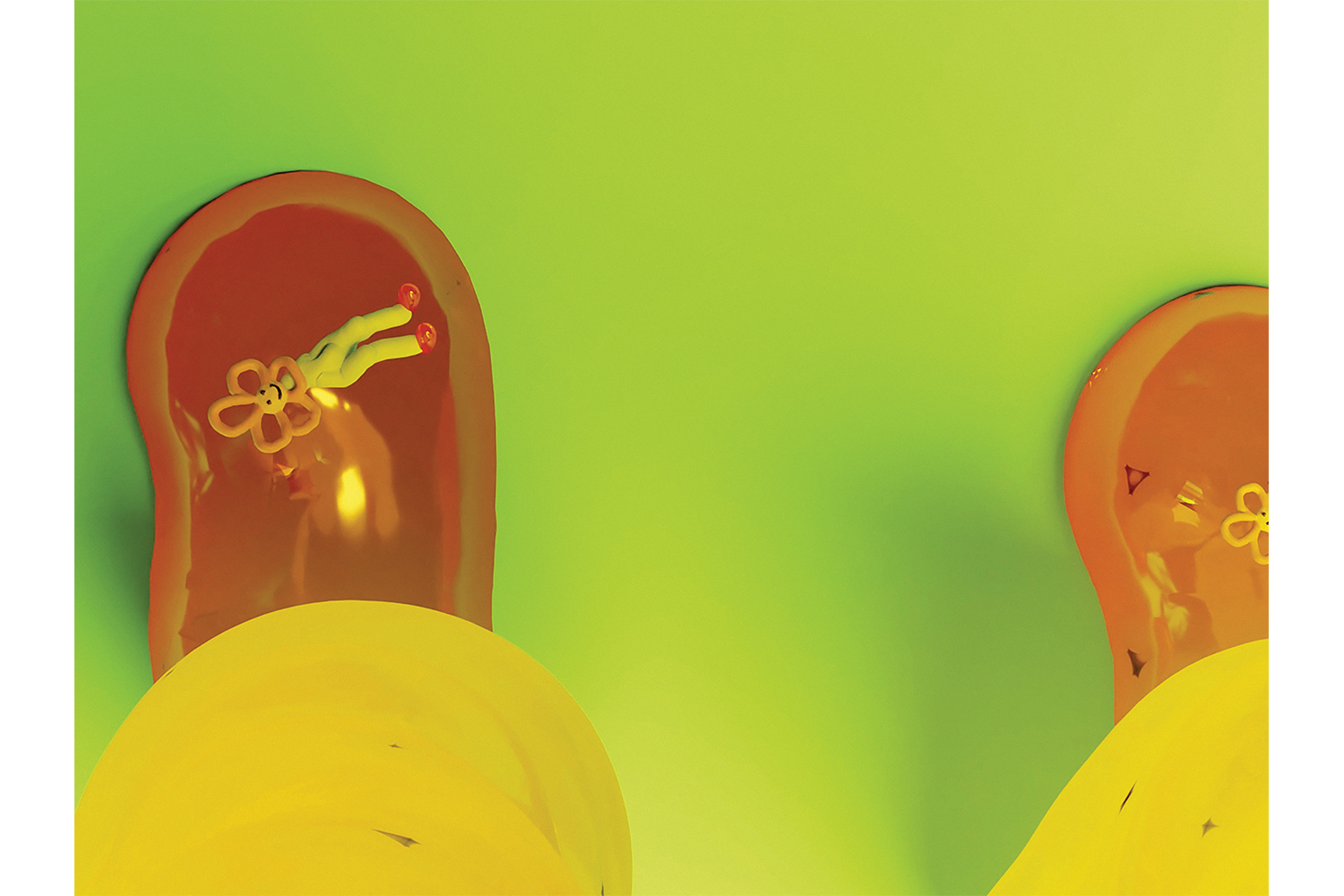

IH: I want to hear about the videos you did with Austin Lee. They’re really fun. The characters are all jelly guys. [laughs]

OK: They’re fucking jelly! Austin reached out to collaborate, and I love his work so much. His world is already so fun and colorful and magical. I showed him some of my drawings or doodles and he really liked working off that and creating a world with those fellas. It’s hard to explain how it was to work with him because it was so gooey.

IH: When you drew the doodles or the drawings, did you think of them as characters for the songs?

OK: It started out with random drawings that informed the house that SAP lives in. I would make that world, put that into a mood board, and then I would draw a play-by- play. Then we would put that into the 3-D program and obviously “Austinify” it. And then after we had our avatars, we would do another storyboard to figure out what’s gonna happen second by second.

IH: I also wanted to talk about some of your other video work, like 2000, the short film. I assume you came upon that footage and decided to make something out of it, but I’m curious, where did you discover it?

OK: I was a child that was very — I was a bit weird and a bit adult-acting. My mom was like, “Oh, here’s this footage of you walking around being like, ‘Oh, this is a skateboard, and this is a stairway.’” She’s kind of just dragging me, being like, “Yeah, there she is! Ten-year-old Kaya, still kind of annoying everybody.” And everyone wanting to be left alone in this house, but me just going for it. It was funny to me, but it’s also strange to be like, “Fuck, I’ve been the same dude.” I couldn’t really be in their reality; I had to document it. I am now, like, “I have to record and document stuff to live.” [laughs] I was fascinated by how early that started. I still feel the same. I approach my life the same way.

IH: What makes you say that you’re the same person in terms of creativity? Curiosity?

OK: Creativity, curiosity, needing to document to understand things. Weirdly spongy.

IH: This album is so much about consciousness and being inside your mind. How difficult is that to translate into words and melody? Like the song “Inside of a Plum,” which is you talking about the experience of ketamine therapy.

OK: I think that’s what we all do. We’re just like, “How do I amplify this?” Or at least, “Why does this feeling matter? And why do I have to say it? And how do I do it?” That’s basically my little checklist before I just take off. But I don’t really know what happens after that. I guess I try a lot of stuff. It’s kind of magical when it works. This thing that we don’t really know — we know where it comes from, but we don’t know how it comes out, or why it comes out in this way, or why we have to do this, or talk about it, or look a certain way, or read a certain way.

IH: One line that really speaks to this that I wanted to ask you about was, “Even my subconscious is self-conscious.”

OK: That was a very specific feeling of leaving the ego and becoming this stretched thing that is maybe time and maybe nothing, and maybe just a little bubble in the soul heaven there. But then all of a sudden being like, [lowers voice] “My name’s Kaya, and I’m a human with a body.” It’s like my consciousness is trying to reel me in because I’m dead. I would highly recommend it to anybody. It’s a bit scary, I guess.

IH: I really love the humor in all of your work, the sarcasm or wittiness or tongue-in- cheek elements of it. Do you think you’re a naturally funny person and it just comes out in the music?

OK: Isn’t there that meme where someone’s like, “Oh yeah, I’ve been told I’m a naturally funny person.” [laughs]

IH: You’re like, “I’m actually hilarious and I should be a standup comedian.” [laughs]

OK: [laughs] I do think comedy and humor has saved me. I want to laugh a lot, which means I probably want other people to laugh a lot. So, it’s maybe a love language thing, or it stimulates my brain. Fuck around with words, they don’t really matter anyway. At least if you can get a little belly laugh in there.

IH: Especially when it’s dark humor — [in the song “Jazzercise”] you say “jazzercising your nerves away,” as if that could solve the problem of anxiety. It’s almost a way of, not neutralizing, but processing that emotion.

OK: Possibly both. Yes, it is a way to laugh about it. [sings The Cure’s “Boys Don’t Cry,” laughs]

IH: In the last two years you’ve been prolific, making a lot of things in different mediums.

OK: I don’t feel very prolific at all. I just feel that I have to do stuff in such a desperate manner, and I will go insane if I don’t do all this stuff. I don’t know if that’s what people talk about when they talk about being prolific, but whatever that is, I have that.

IH: When I usually hear that word tossed around, it’s about productivity, which is a very weirdly capitalistic way of thinking about art. I was just interested because for a lot of people in the pandemic, it was very hard to create.

OK: It’s my little life raft, but I think it has been forever. And then obviously it was highlighted when there was literally nothing else to do.

IH: You talked about documenting things as a way to process. I feel like the idea of documentation is different from the intention of making an artwork.

OK: Regardless of if there’s a camera here between us, we’re still looking at each other through these ancient fucking machines called eyes, documenting everything that we’re doing. And that kind of freaks me out all the time, but it’s something nice to think about. Documenting something and putting it on a piece of plastic, for example, and putting it into the world is a great practice. But I’m more aware of looking at everything through my eyes and being slow and thinking about how the wood on this table feels, or whatever. I don’t smoke weed, but it just sounds like I do. [laughs]

IH: [laughs] The last thing I really wanted to ask you about was the piece that you’re doing at the Musée d’Orsay in December.

OK: I made a piece in September for the Munch Museum, where I read a lot of Edvard Munch’s diaries. I made a piece out of that and his poem that’s about a wild bird of prey, and it’s a wild bird of prey that’s stuck inside of his chest. And its wingspan is darkening his mind — it’s about depression. So, this will kind of be a sister sibling piece to that. I go to this church in Oslo, and I listen to this person play the organ. So now I’m gonna make an organ-ish piece where I might try to flip perspectives from Munch and his bird to a lover of Munch. I thought I could try to make a hot girl song where she is owning up to the darkness. Because a lot of people who read his diaries are like, “I can’t believe it! He’s so misogynistic.” Wait, what if that woman was actually like such a horrible…[trails off, laughs]. So, I’m gonna try to make like a horrible vampire character. She puts the doom in mood.

IH: What elements do you think it’s going to have?

OK: There will be singing. There will be organ. There will be harp, but it will all be backtrack. I’m not really sure how I will be around everything, but I hope to make something that I can interact with as a hot girl vampire lover of Munch [laughs].