“Carolee Schneemann: Body Politics,” on view at the Barbican Centre, begins with paintings. The opening text reads: “I’m a painter. I’m still a painter and I will die a painter.”1 It is important to begin in the indisputable terrain of visual art, and to hear from Schneemann how we should think of her. In the time between the making of her early paintings and this quote from the 1990s, Schneemann would make Meat Joy (1964), a joyous erotic rite; Fuses (1964–67), a film of the artist and her partner James Tenney making love; and Interior Scroll (1975), a live reading from a scroll extracted from her vagina. That she would continue to define herself a painter seems a category error. However, upholding the sanctity of categories would perpetuate the “Art Stud Club” dogma that Schneemann spent her career dismantling, as exemplified by this exchange between a Structuralist filmmaker and Schneemann: “He told me he had lived with a ‘sculptress.’ I asked, ‘Does that make me a filmmakeress?’ ‘Oh no,’ he said, ‘we think of you as a dancer.’”2

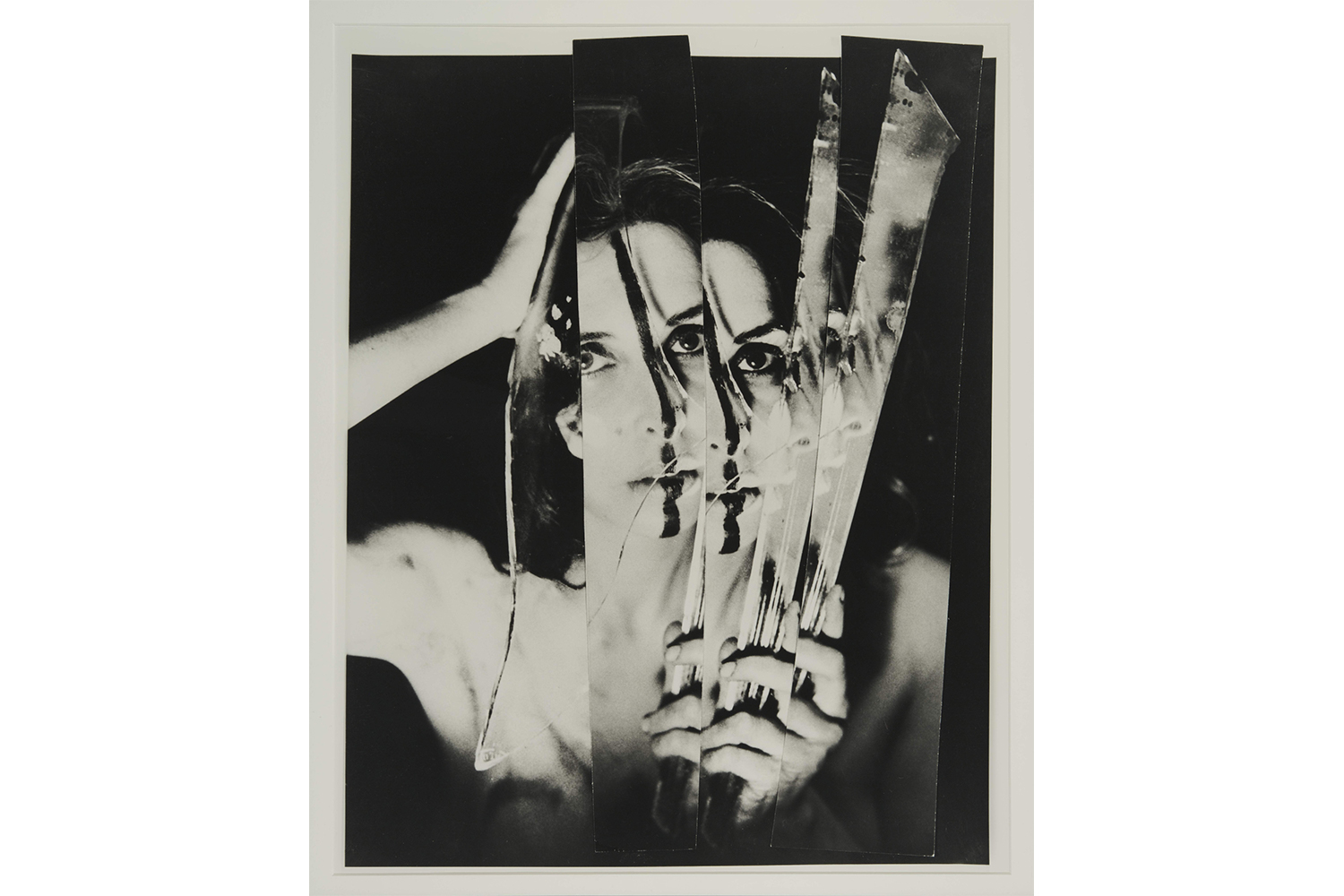

“Body Politics” overturns any assumption that visceral and visual are irreconcilable categories. A resolutely optical focus pervades the entirety of Schneemann’s output, spanning kinetic paintings, collages, box constructions, photography, choreography, film, performance, and installation. These interpenetrating media all share a commitment to “image.” And that “image” is an image that thinks, feels, fucks, destroys, and makes (images).

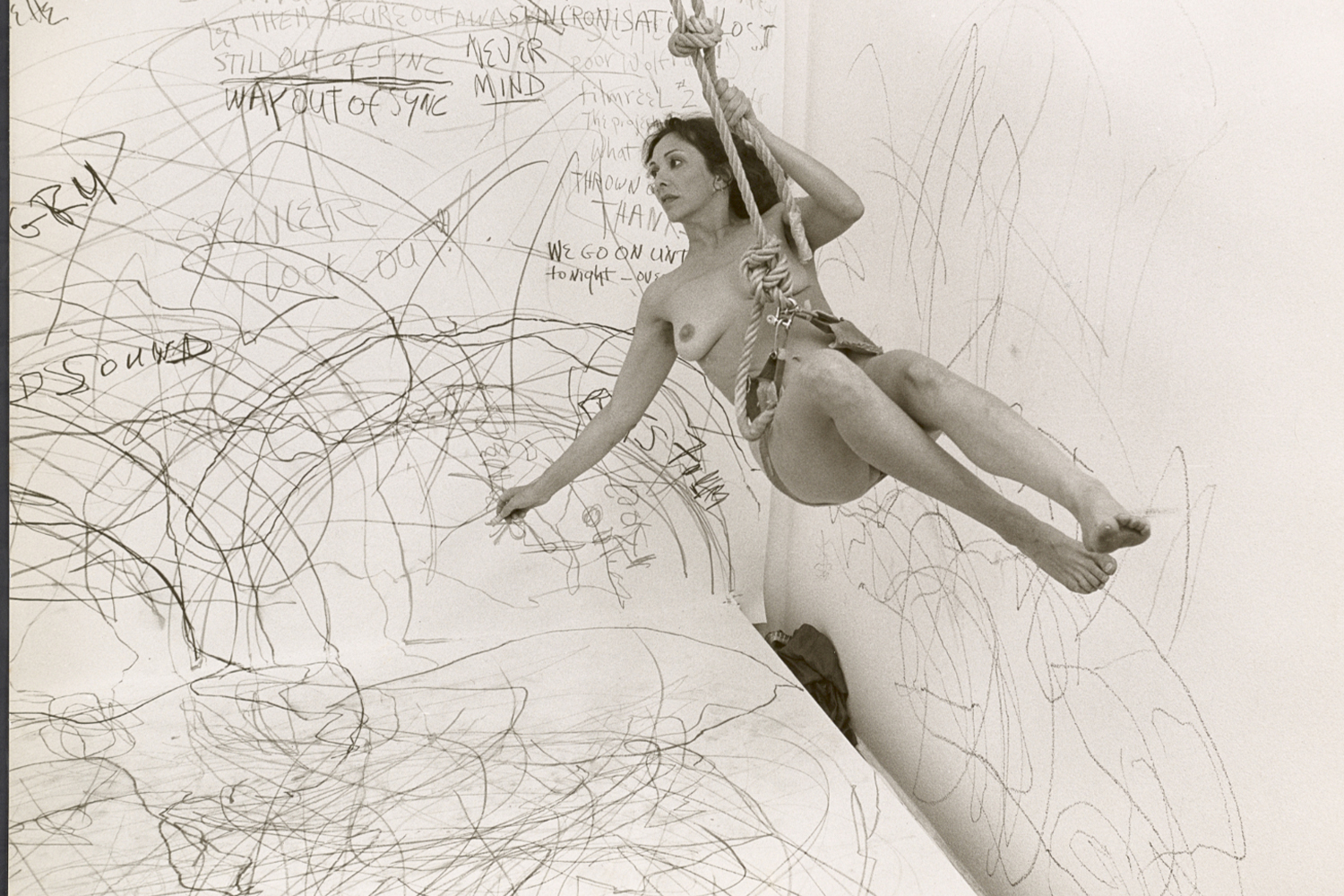

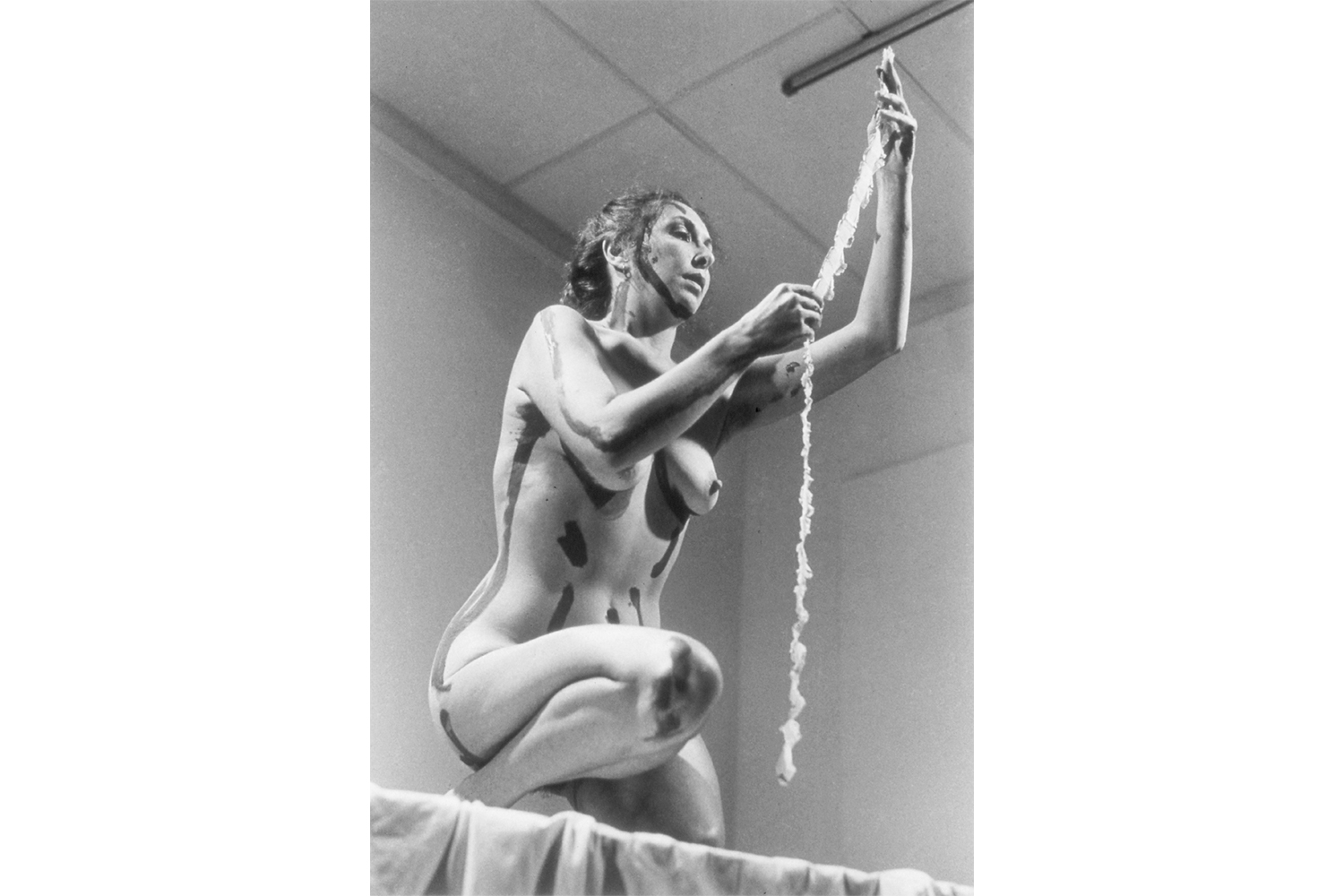

In the 1950s, painting was a visual art, god damn it! Vision was still venerated as the most trustworthy sense, elevated to the realm of disembodied reason. The eye orders. The body undoes. But Schneemann advanced: “The body is in the eye; sensations received visually take hold in the total organism. Perception moves the total personality to excitement.”3 Her Eye Body: 36 Transformations for Camera (1963) confirms body as both image and image maker.

Understanding vision as an “aggregate of sensations,” Schneemann saw the body-in-space-time as an extension of painting.4 The film Fuses sought to “see what the ‘fuck’ is,” yet we do not “see” the fuck in the literal glare of pornographic availability.5 The celluloid is baked, burned, eroded. Through these marks we glimpse penetrations and digressions (including Kitch the cat). Schneemann utilizes the technique of nonlinear montage, presenting the fuck from her view, James’s view, Kitch’s view, the camera’s view, all of which collapse into an indissoluble relational ecology; a view from everywhere.

Schneemann was an avid reader of Wilhelm Reich, for whom the orgasm functioned to release energetic blockages (and societal repressions). And it seems the orgasm was not the subject of Fuses but its formal principle. She “wanted to put into that materiality of film the energies of the body, so that the film itself dissolves and recombines […] as one feels during lovemaking.”6 The later Vulva Morphia (1995) mocked attempts to confine women’s sexual pleasure within discourse — as sign, pathology, or chemical programming.

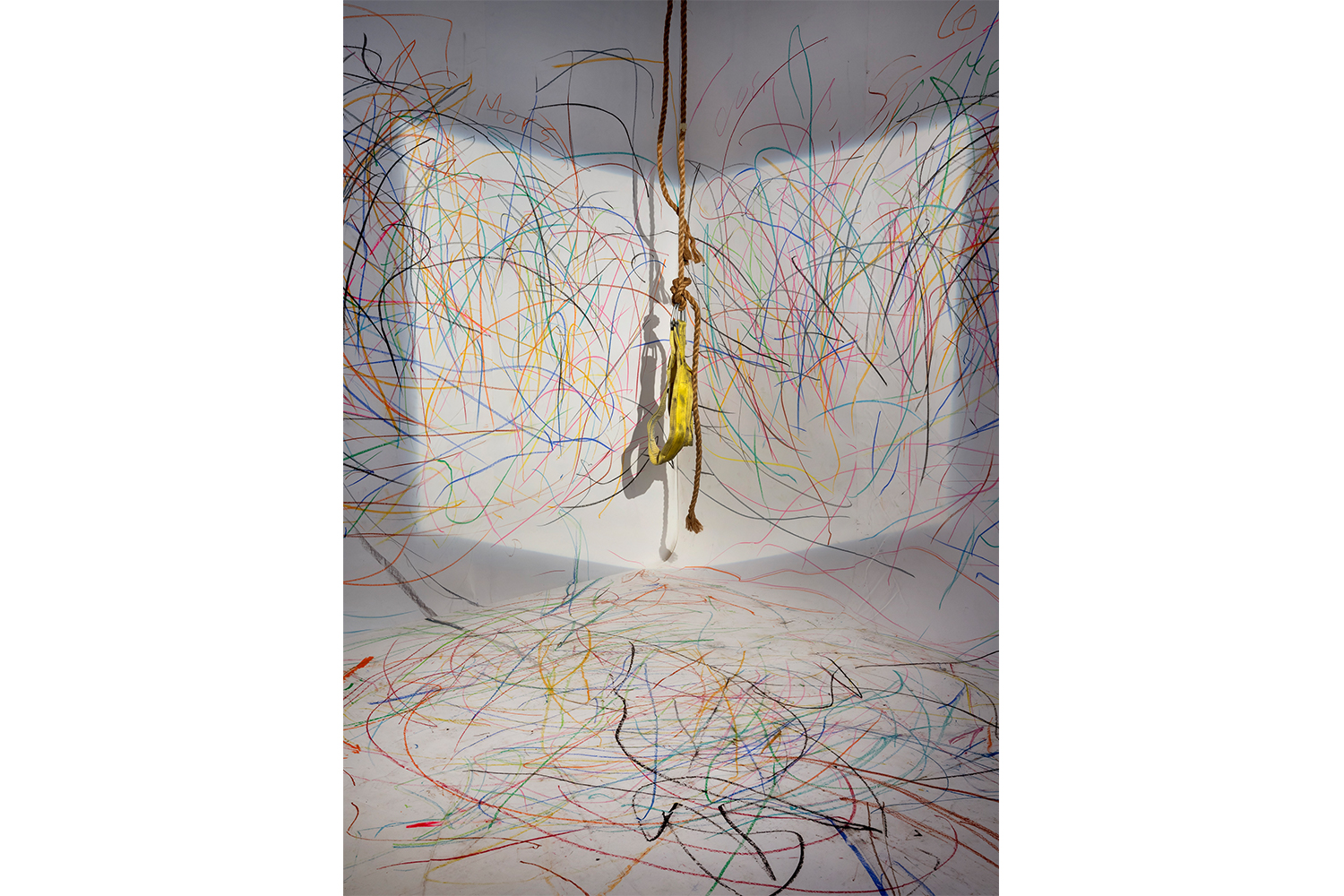

Her refusal of dominant frameworks led art critics to discredit the work as “brainless,” “clutter,” “mess.”7 This is laughable, as the instructions, notations, scores, and diagrams within “Body Politics” demonstrate; Schneemann’s work was meticulously planned. “There are a lot of rules to Meat Joy […] it took about fifteen rehearsals.”8 In the show’s final rooms we encounter that which is truly brainless, which creates the most horrifying clutter, the most devastating mess: not the female body, but war.

Schneemann’s later work addressed the suffering inflicted by destructive militarism. Tasked to bear witness to atrocity, here detached image consumption is impossible. Schneemann made images spill out and seep in. The translucent curtains that frame the route through “Body Politics” reference that permeability as sounds leak through: whirrs, crashes, the croon of “Sexual Healing.” The most affecting (and insistent) sound comes from War Mop (1983), a household mop repeatedly falling on a television set that loops footage of the war in Lebanon. Viewing the harrowing images, one sees-hears-feels the intrusion of war into the domestic body, the female body, who will clean up the mess.

“Body Politics” surveys the pervasiveness of power structures — in laws, wars, illness, animal and carceral captivity — that anesthetize bodily agency, pleasure, and knowledge. These are painfully live concerns. The exhibition is at once an epic of optic-erotics, a jubilant transformative force that explodes the established order of things, and a becoming body without organization.