In installations with multi-channel sound sources, Mobarak mixes the words of her polyglot father, whose memory is failing, with the voices of people she meets in public spaces, whose testimonies she collects on public benches. The artist works with mycelium and mushrooms, which she considers to be her assistants, collaborators, or fabricators. She uses bodily substances and industrial residues, intimate and public detritus, to produce sculptural and pictorial ensembles that continue to develop a singular autopoiesis. Her economy of materials (recuperating shipping creates from a gallery, bodily substances) contrasts with the care and precision of the installations. It takes several listenings, immersions, and temporal experiences to hear the echoes of this work, which then linger like love at first sight.

Born in 1985 in Egypt and raised speaking Italian as a toddler, which she has since forgotten, today she is fluent in French and English, spending most of her time in the United States while traveling routinely all her life to the multicultural territory of Lebanon – she is a dual citizen of these two countries. The artist has developed a syncretic practice with a somewhat tragicomic philosophy — which is the strength of many uprooted, transplanted immigrants. The fall of the Berlin Wall, the end of ideology, and post-consumerism are all remnants of history that become raw material for the artist. Mobarak transforms tragic situations (the breakup of a love affair, the loss of memory, exile) through humor, turning them from “gloomy” to “glowy.” The costumes and the colorful sets she invents for her musical performances reflect a global economy. As a musician, she composes polyphonies combining glossolalia and opera, snatches of conversations and old-fashioned ritornellos. Meta-historical and transcultural, intergenerational and interspecies, Mobarak’s work symbolizes a plural form of “operativeness.” It also manifests a will to eradicate (smash) gender hierarchies, conventions, and codes that structure this contemporary “materialology.” In this, it goes against the programmed dematerialization of works and makes them verbi-voco-visual experiences. This subterranean “counterculture” is woven from a deep symbiosis with art history (from Kurt Schwitters’s Ursonate (1932) to Laurie Anderson and John Cage), a dialogue with recent theories in astrophysics and biology, and a noble-looking punk style.

Nour Mobarak’s polymorphic work corresponds to a contemporary poetics situated within current questions of posthumanism. The end of dualisms (nature/culture, man/woman, innate/acquired) and the opening up of a new epistemology regarding the self-organization of living matter form the soil of her practice. This is exemplary of a postapocalyptic (post-Chernobyl, post-9/11, postcolonial) generation that embraces new relationships, no longer waiting for a potential hero but reinventing what remains, letting it grow and germinate. Mobarak understands that metamorphosis is the principle that moves the universe.

Marie de Brugerolle: Let’s start with our meeting in your studio in Chinatown, Los Angeles, near LACA (Los Angeles Contemporary Archive).1 You were working on a series of sculptures for which “mushrooms” were your “assistants.” Can you tell us how this started?

Nour Mobarak: My father has a neurological disease that allows him to remember the present moment for only about thirty seconds at a time, even while he still continues to perfectly speak Arabic, Italian, French, and English. I was recording our conversations, and around the same time I started growing mushrooms just as a hobby. The biological political economy of symbiosis and decay in mycelia and its plasticity led me to very much want to work with them as a sculptural substrate. I was drawing parallels between my father’s decaying mind, the structures of our conversations, the way his atrophying brain looked in MRIs, the white blocks of mycelium, its structure, and my own practice. I decided to turn columns of fungus into speakers that broadcast cyclical polylingual conversations with my father from the left, and my improvised songs from the right. Once I set up the mycelial production aspect of the works, my job was to go to my studio and just observe. That was not so different from the long silences I’d also have with my father sometimes. So that’s what was going on when you came to my studio in 2018.

MDB: It seems that your way of working follows a compositional method using a false randomness that is indeed close to music. I think about John Cage, another mushroom lover, but also in terms of the hybridity of your work.

NM: I found out about Cage’s relationship to mushrooms after my own journey started, and I was pleased to discover it. In terms of “hybridity” in form, my work started with language. I’d write a lot of fantasy and science fiction when I was very young, and poetry later, and I was thinking of so many ideas in language that I wanted to actualize into different materials.

MDB: This creates polymorphic and polysemic forms. In music, multi-channel installations; in sculpture, layers of time and materials; and in poetry, sequences of rhythm.

NM: I suppose I feel comfortable when works are nested, transposed, transferred, repeated, and fractal. It’s like that Suburban Lawns song “Janitor”:

All action is reaction

Expansion, contraction

Man the manipulator

Underwater, does it matter?

Anti-matter. Nuclear reactor.

Boom boom boom boom.

I want all things to be known as something else because all things have an intersensory equivalent.

MDB: We could speak here about the use of spherical forms, recently shown at Hakuna Matata — an outdoor project space in the Mount Washington neighborhood of Los Angeles (the series “Sphere Studies” and “Subterranean Bounce,” both 2020) and in your solo show “Logistique Elastique” at Miguel Abreu Gallery (“Sphere Studies” and Reproductive Logistics, 2020 and 2020-2021 respectively). This reminds me of the celestial music of the spheres, and Peter Sloterdijk’s series of essays Bubbles (MIT Press, 2011). But I know it is a real, deep question for you.

NM: For me there was an element of K.I.S.S. — Keep It Simple, Stupid. I wanted to give form to decay and negation through mycelium spheres, and I wanted to give form to the ephemerality of sound in a visual way with the sound piece Subterranean Bounce. For that I recorded the sounds of spheres of different materials and sizes rolling and bouncing around the room in five channels. At Hakuna Matata, I buried the amplifiers broadcasting the bounce underground, under the site of the spheres. The sphere is mesmerizing, it’s voluptuous, and it has this incredible feature of being a shape. All matter in the large-scale universe tends to fall into gravitated orbits and create variations on spheres. Interesting to bring up Sloterdijk’s Bubbles; Hito Steyerl also refers to bubbles in her “Bubble Vision” lecture, where she connects spheres to portals of virtual reality and bubble financial markets (which relate perhaps to Reproductive Logistics). And what of the bubbles formed in mycelial decay to archival senescence? It’s almost a bubble petrifying its own burst. The sphere is rich, and each of the “Sphere Studies,” one through six, ended up proposing their own 360 lenses, which I described in a short text I published in the Hakuna Matata show’s catalogue only after spending time with them.

MDB: At Hakuna Matata, but also at LAXART, Los Angeles,2 The Hammer Museum, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, you used multi-channel sound systems. Can you explain why six or sixteen channels create a specific “sphere effect?” This made me think about La Monte Young, especially with the use of ambient light.

NM: As the body or listener moves through the space, the body or listener is choosing what they listen to. There’s never one version of the piece; you’re composing it with your own movement. There’s a constant recomposition, and a psychoacoustic element with the harmonics. With Toothtone (2019) — in Nancy Lupo’s exhibition “Scripts for the Pageant” in San Diego — I turned each one of Lupo’s benches into a speaker by suspending clear acrylic panels with transducers from the underside. Out of each bench came the voice of someone who I had interviewed in Pershing Square. Standing in the center, there’s the experience of being in a room full of people. Sitting on any one of the benches, one not only hears a voice but also feels it through the reverberations of the bench through sound. Sixteen channels are used here because that’s how many benches Nancy made. And six allowed for an envelopment of the sound space in another sound piece, Allophone Movement. I conceived Subterranean Bounce with five channels because I wanted to create an X-formation from the ground.

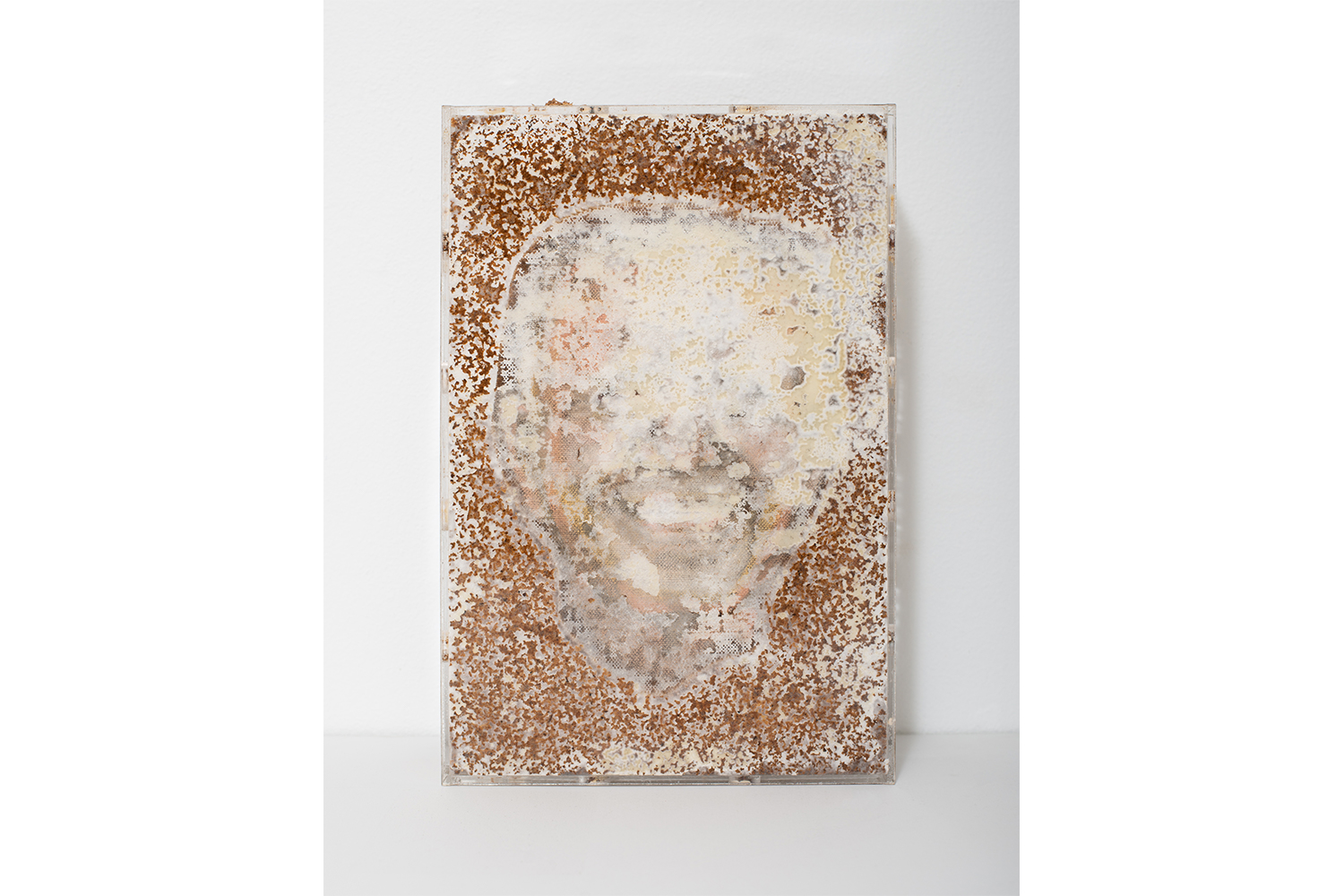

MDB: The mycelium that you use in the Miguel Abreu exhibition has a specific mode of reproduction. Could you describe this in relation to the piece Reproductive Logistics? In this work your portrait made from a canvas with “impregnator” traces (sperm, hair, body fluids…) plus paint is “eaten” and transformed by the Trametes versicolor? In a way the crate-canvas is a Petri dish…

NM: Mycelium can move between self-reproduction to sexual-reproduction, triggered from one to the next when adverse conditions appear in their environment.

MDB: Organic material and chemicals are hybridized in the “Spheres” series and Reproductive Logistics. Is it a metaphor for the ongoing “metamorphosis” at stake in our world? Eating, being eaten?

NM: Some of the hair that was embedded into my piece Reproductive Logistics was given to me by my first potential impregnator after we broke up. He showed up at my job, handed me a Rite-Aid bag and said, “Here’s my bag of hair.” I use hair and sperm and mycelium in Reproductive Logistics. I use plastic and mycelium in Horse Head (2020). I use mycelium and hidden whiffle balls in the “Sphere Studies.” With Reproductive Logistics, the work pretends to plot the external circumstances that have dictated my ability to reproduce — both as an artist and biologically. I use mycelium as the substrate within which I embed things like lovers’ hair, sperm, a color code of past potential impregnators in sequential order, and a self-portrait made from the colors of the color code. There’s a metamorphosis, a decomposition, and recomposition of all of these materials. The work is eating itself.

MDB: You integrate the notion of cycle and different states of presence in Father Fugue (2019), your first full-length album, which is both rooted in neurodiversity and also could be a metaphor for the transformation of language via migration. Speaking benches re-create an “agora” or give voices to people who are “invisible” in the streets. Especially in LA. Was it a response to a specific context?

NM: When Nancy asked me to make a performance for her benches at Pershing Square, I had just finished performing my works Allophone Movement (I–IV) and Phoneme Movement (I–VII). There I composed tracks out of the sound components of language (“allophones” and “phonemes”) using either my own voice (in Phoneme Movement) or the recorded voices from the UCLA phonetics archive (in Allophone Movement), and I perform over them by moving around the space and vocalizing throughout. The compositions come out of six channels surrounding the room, and I vocalize a cappella, sometimes directly into a single audience member’s ear, or while collapsing repeatedly, or while running, or from outside the venue. As I wanted to continue exploring the voice as material, I decided to use the voices of Pershing Square. I spent a month approaching people and asking them if they’d like to let me record their voice for up to an hour for twenty bucks. I had no real criteria when approaching people. I asked few questions and people talked and talked. The benches vibrate with their voices, and as you sit and listen to these people talking to you, you feel them inside you through the physical reverberation.

MDB: It is a kind of literal feedback effect of a political fact. Here I think about Felix Gonzalez-Torres and his works in the public sphere. I think also that it is meaningful to go to Greece and “reenact” Daphne today. What are your thoughts on the question of “reenactment” in opera and music and what we call “performance” in the visual arts?

NM: The piece I’m developing for Rodeo Gallery in 2022 is an interspecies tableau vivant, restaging the first opera, Jacopo Peri and Ottavio Rinuccini’s Daphne, which was based on Ovid’s story of Daphne. I’m growing sound sculptures out of mycelium and translating the libretto from 1598 into different languages based on their morphophonology, in an attempt to make an opera with the widest palette of sounds from the human voice. Now, is this a performance? I don’t really know. But one thing I can say was that I never intended to be a performance artist. I’d go to a lot of shows, and see someone like Hart [Gledhill] from The Hunches in 2006 get completely trashed and fully absorbed in the sound and throw himself around the stage and into the audience, and I liked that. I love seeing Sufi whirling dervishes, or seeing Prince perform “The Beautiful Ones” in Purple Rain, or even Charlemagne Palestine’s Body Music. The feeling of being transported to oblivion — I think it’s important that humans have a space for that. And art is a good space for that. How does that work with “reenactment”? I feel like you can get there no matter the content, medium, or genre. It’s more about using presence with full commitment and integrity.

MDB: To get back to “painting” and the recent new works in process: for Reproductive Logistics you use a specific kind of material but also a specific way of shipping. Can you tell us about it?

NM: Reproductive Logistics was about material circumstances that dictate the supposedly chosen manifestations of self. I’d conceived of this ambitious work, but wasn’t sure if I had the budget to crate and ship it from LA to New York. This fact was so present in the conception of the work that I wanted it to become a facet of the thing itself. Vielmetter gallery advertised a free shipping container. It made sense to make the work to fit the shipping crate, rather than the shipping crate to fit the work, considering all else that I was doing with that piece. So I grew the mycelium canvas into the crate.

MDB: We have spoken about the sculptural aspect of painting for the work Reproductive Logistics at Miguel Abreu. Paternal and male figures losing life and memory, mixed with stars and explosions, like snapshots from TV commercials, as if the mycelium is going to help the decomposition of time by attacking the representation. Can you develop this vision of canvas as a vessel for memory?

NM: Yes, I’m now making these paintings of memories and embedding them in mycelium to be warped and reinterpreted. The subjects of the paintings themselves are incidental. I want them to act as a vehicle for the mycelium itself to become a picture of the recomposition of reality that happens through subjectivity and time.