“A screen is fundamentally an architecture of psychic transfer and tracing. It is also a space haunted by the maternal.” — Giuliana Bruno

“So there’s a new kind of space travel,” explains Rosalind Nashashibi in her most recent film, “which uses nonlinear time.” What’s it for? A friend asks. “So you can travel in space without losing all your loved ones.” The dark melody of that answer, constructed equally of beats of ardor, anxiety, longing, and the violence and virtuosity of temporality, keeps a strange time. Listening to it, and thinking of the way myriad forms of displacement structure and condition our time, I asked myself: Are all of our large and small exiles and (the hoped-for) assimilations a kind of space travel, one not given to strictly linear interpretations of space and time? Is contemporary life itself, with its valences of desire and displacement and community and shelter? Yet as the artist notes, the problem is that if you tried to switch back to linearity, you could “no longer understand each other at all.” What resolves this nearly fatal alienation is that one crew member begins telling a story — the linearity inherent to the form saves them all.

Relation, understanding, the longing to be understood, to be cared for; mechanisms of kinship, narrative, and the maternal; the performance and projections of representation, identification, and rehearsal; the constant loop of political violence (economic, military, or other) and migration and the carceral constellations of borders such loops trace; the cost and necessity of perceptual memory and the aesthetic record: such are the many threads that constitute the warp and weft of Nashashibi’s ever-elliptical and yet unambiguous practice, one mostly preoccupied with film but also, variously, with painting. Her work is at once measured and tender, discursive and associative — that is: relational, always. Her subject is the affective relationships between people — familial, societal, systemic — but also among people and objects (art or other) and institutions, as well as time and place itself.

The story that Nashashibi relates in Part One: Where there is a joyous mood, there a comrade will appear to share a glass of wine (Winter, Spring and Summer) (2018) as she vacations with her children and friends on the Baltic coast of Lithuania is Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Shobies’ Story (1990) (though the film’s title gleans a line from the I Ching). Le Guin’s novella follows a group of space travelers from different planets and of different ages stationed on the same ship, chasing nonlinear time in the weightlessness of dark space. In some sense, it is about the strange virtuosity of chosen, non-nuclear families and the exemplary difficulty of community, and the shifts and gaps in time and space, and understanding and affinity, that they reveal. It is also about storytelling; that is, making art. Consequently, the novella might stand as a thesis for Nashashibi’s film, which with its poetic pacing, pointed conversations, and easy, disquieting beauty, meditates on the social roles we inhabit in group formation, both in private and in public, as a matter of course or necessity (though maybe these are the same thing).

“We are born in linearity,” Nashashibi notes in Part One. Are we, though? Considering the true travels of our lives, our many disorienting loops, it can seem as though ideas of progress (that is: linearity) are just that — ideas. Forms as fictional as any other. To that end, Part One has the dreamy, ambient feeling of the fictive and the diaristic being woven together — it is as if the strange politics of the parable and the documentary are meeting on some soft, cinematic shore — as well as the soft-focus seventies-era palette of most of Nashashibi’s 16mm moving-image works. As is her wont, the narrative is not progressive but multiple and social and systemic — it seems to extend and refract in all directions, a kind of kaleidoscope of subjective details and moments, their affiliations and resonances. Her stay on the blue-and-gold Baltic coast is punctuated by trips to an Edinburgh museum, where Emil Nolde paintings — of whose familiar yellow fluorescence and patient blues he wrote “every color holds within it a soul” — are studied, and visits to the London studio where Nashashibi’s own paintings are shown.

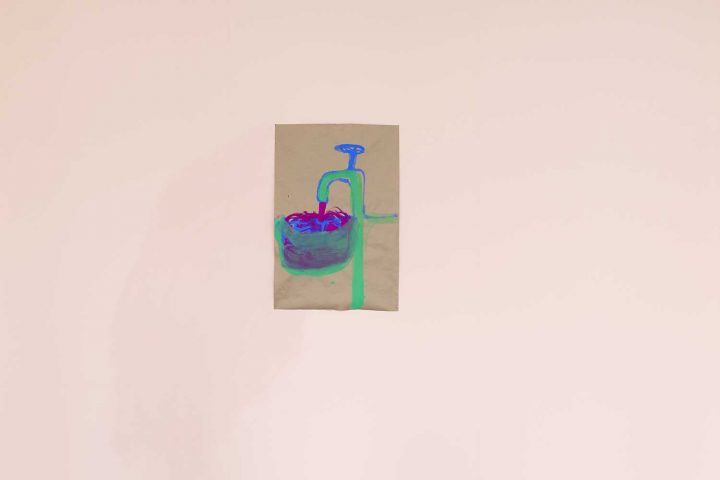

Those latter paintings, Nashashibi’s — on view in her exhibition at the Witte de With, in Rotterdam, in late 2018, alongside Part One, all curated by her friend Raimundas Malašauskas — move easily between biomorphic abstraction and figuration, something organic and aching, the pastoral and the social. They conjure, for me, Arthur Dove or Nolde himself. The incandescent oeuvres by these two modernists from different continents were framed by world war, and Nashashibi’s paintings have some of the same strange electricity and melancholy. Painted and sometimes hung with women’s stockings, her paintings have a loose frisson, a dark affection. Their palette rhymes with that of Part One, emphasizing the formal choices and the specific sensibility of the artist behind both. Indeed, despite the fluent beauty of her films and paintings, Nashashibi seems intent on undercutting their immersive aspects — she wants the viewer to be aware that she is watching a film, that she is looking at paintings, and alert to the fact that these works, artificial forms crafted from the material of the universe, have aesthetic precedents.

Thus, Part One (2018) reminded me, in its full title, and the further films it anticipates, of Éric Rohmer’s late-career seasonal quartet, Contes des quatre saisons [Tales of the Four Seasons, 1990–98] which are similarly concerned with affective relations and the currents of kinship, place, and season, the social mores that infuse and propel them. But as a dreamy document of social life and art chatter, and its partly Lithuanian setting, Part One also evoked Jonas Mekas, whose long New York exile, in the wake of a youth defined by fascist violence and forced displacement, has yielded an oeuvre of diaristic films with an affection for experience and place. Though Nashashibi’s films are more formal, more ascetic, in their way, their deliberate distanciation does not preclude the deeply empathic and sensual tonalities that mark them.

Born in 1973 in Croydon, London, to a Palestinian father and a Northern Irish mother (such parentage raises the question, in radically different contexts, of the arbitrary inelasticity of colonial borders), Nashashibi studied at Sheffield Hallam University and the Glasgow School of Art. She has worked mostly in film since, though her paintings increasingly accompany her moving-image works in her exhibitions. Nashashibi was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2017, the same year she presented two new films in documenta 14 in Athens and Kassel. Why Are You Angry? (2017), made with longtime collaborator Lucy Skaer, takes its title from a painting by Paul Gauguin. It also appropriates, in a fashion, Gauguin’s depictions of and projections on Indigenous Tahitian women. Questions of representing women and the gendered, racialized “other” are raised, as is the colonial white male gaze, its fantasia and fetish, but the film’s field of inquiry is more concerned with how women of various generations create community, and how they share space, “natural” or other.

Such an interest — replete with another neocolonial tropical backdrop — also centers the film Vivian’s Garden (2017), which follows mother and daughter artists Elisabeth Wild and Vivian Suter (fellow participants in documenta 14) in the jungle compound they share in Guatemala. After making the film, Nashashibi noted of the two: “I think it’s remarkable how they live, these two older women, mother and daughter; the mother is in her nineties, the daughter is in her sixties, and both artists making work every day, no matter what.” Speaking of the Mayan workers who care for Suter and Wild, Nashashibi says: “They have a sort of mini-economy there, which in a way is a sort of colonial situation at the same time, also a postcolonial situation. Also a very carefully managed and nurturing way of living together and working together.”

Martin Herbert has written that “Nashashibi has long been concerned with how we accommodate ourselves, or don’t, to inherited institutions.” Perhaps one of the great institutions (great meaning vast, insidious, and incalculably intrinsic to our present) we have inherited is colonialism, and the dialectically related institutions of displacement and dispossession. Suter and Wild’s lives have been defined by all of these, as have the lives of the Mayans who work for them. Wild was born in Vienna in 1922; in 1938 her Jewish parents fled to Buenos Aires. In Brazil in 1949, Wild married a Swiss exile and had a daughter, Vivian. A decade later they in turn fled the political violence of Brazil, which would experience a coup in 1964 and the installation of military dictatorship. They settled in Basel for three decades before once again leaving — this time, in 1996, for Panajachel, where mother and daughter have lived since. Though the Guatemalan Civil War ended that year, the country continues to experience political violence, particularly against the Indigenous population (the Mayan genocide, carried out by the US-backed Guatemalan army until the 1980s, is also called the Silent Holocaust).

That it is these people who also care for Suter and Wild, two white European women living and working in a kind of third (now self-imposed) exile — and that all of their lives, Mayan and European alike, have been shaped by genocidal violence — makes this story strange but also emblematic of the crosscurrents of fascism, racial capitalism, and coloniality in the twentieth and twenty-first century. But the flux of time and inheritance that Nashashibi examines is not only political but maternal, matrilineal, emotional, and art-historical. She has written of Suter and Wild: “They are as close as maiden sisters; each is at times mother and daughter to the other, and sometimes they are my mother and my daughter too.” In a space of nonlinear time, they could be — and perhaps are. Nashashibi’s reflection reminds me of something a friend, the artist Rallou Panagiotou, who recently gave birth to a daughter, said to me in the months after, likewise suggesting this kind of psychic and maternal transfer: “It felt like she was giving birth to me in some sense, that I was in fact her daughter, and that she is now my mother, the steady, wise one around which our family turns.”

In an essay on Chantal Akerman, Giuliana Bruno once wrote that “a screen is fundamentally an architecture of psychic transfer and tracing. It is also a space haunted by the maternal.” This maternal haunting seems to shadow Nashashibi’s recent cinematic explorations and projections (likewise her paintings), but the ever-mutable and nuanced relations of care — maternal or otherwise — between bodies of different ages, classes, races, genders, stages, roles, communities, and displacements, is not a new subject for the artist. See the film Lovely Young People, (Beautiful Supple Bodies) (2012), which shows groups of older women, young families, and policemen from Glasgow’s Southside, watching a rehearsal of the Scottish Ballet. The images of older women watching the dancers is profoundly moving — these are images of desire, alienation, memory, longing, and projection. That is, they are images in which time, its lucid materiality, its relentless back-and-forth across some mythic river, becomes palpable — temporality as figured in the distance between the taut, sweaty muscles of the dancers, and the ever-more-clothed and sedentary audience, their faces crossed with awe, attraction, sadness, and wry bewilderment, that watch them.

To say (to write) that film is about looking, is about the desire to look, is about the erotic gaze, is almost ridiculous — of course it is — but some artists, like Nashashibi, regularly reaffirm this fact. This looking, and the deeply complicated erotics of these optical encounters, has a point, though: it seems the artist is radically committed to seeing (that is, understanding) how one lives and works in our ever-imperfect and unjust world order, and thus how one transforms this inherited world, with its lines of distance and systemic violence, into something livable and workable and at times virtuosic, something equal to one’s dignity and desires (for love, care, work, a home, and art).

Thinking about Le Guin’s speculative and nonlinear time-travels (into fiction and without), and the exiles of so many of Nashashibi’s filmic subjects (both individuals and communities), I began considering those lines from Part One again, in which the artist notes: “There is a new kind of space travel that uses nonlinear time.” Though travel is often articulated as a progressive, forward motion—traveling to a place—much travel is actually forced, it is from. It is predicated on what is left behind—both people and place and the lives they might have borne. This kind of travel articulates what was left; it suggests the lives we might have led and, possibly, the choices (and lack thereof) to come.

As Malašauskas notes of Nashashibi’s recent work: “By exercising our freedom to belong in, or even peel away from, the multiple dimensions that make up the world, we can come to witness how predetermined our movements are, but also to imagine their possible irreversibility.” In the opening scene of Part One, Nashashibi’s children tumble around in bed, attempting to hide from the camera filming them (at once loosely improvised and classical in form, the film begins at daybreak, naturally). “Why are they filming us?” one child asks, in sweet complaint. Her son’s electric blue pajamas conjure an Emil Nolde figure against the dark red and orange bedsheets. “Because we’re starting the film this morning,” Nashashibi whispers. The child: “Why do you have to do it now?” “We have to start,” the filmmaker-mother answers, patiently, honestly, and, with that, I imagine, some ship takes off into space.