Some whistles are like a kettle. In Nikita Gale’s Chisenhale installation of light, sound, and sculpture, something is under sustained pressure, about to boil over. Other whistles are short, sharp, urgent. They want to command: come back, heel, obey. The whistles activate a light performance in which stage lights attached to steel trusses wheel around, as if in pursuit, strobing and flickering at the beck of the sound.

Gale turns the gallery into a theater of surveillance; the viewer becomes both hunter and hunted. Like her ongoing “RUINER” series (2020–present), in which crowd-control fencing is entangled with concrete-dipped cord in elegant and uncomfortable sculpture, Gale here turns toward absurdity to question the performativity of incarceration. Next to the real stage lights on the trusses are two lights cast in concrete, their cone-shaped beams also cast as floor-to-ceiling pillars. The shape becomes cartoonish, evoking classic animations where a character is trying to hide, and a spotlight keeps appearing in the sky to illumine and thwart them. Light, in its shapelessness, becomes fixed and lumpen. This kind of spotlight is used to divert attention on stage to a particular moment or actor: it creates hierarchy, but is itself invisible. If the theater is an institution, the spotlight is part of the architecture that sustains the spectacle.

As much as the gallery is a theater, it is also a kennel. Metal dog bowls pepper the floor. Leashes have been knotted and dipped in concrete, hung in a constellation from thin wire. The concrete suggests a permanency to this state of capture or control, yet dried stems of lavender sprouting from the knots suggest some warmth or protection may be on its way.

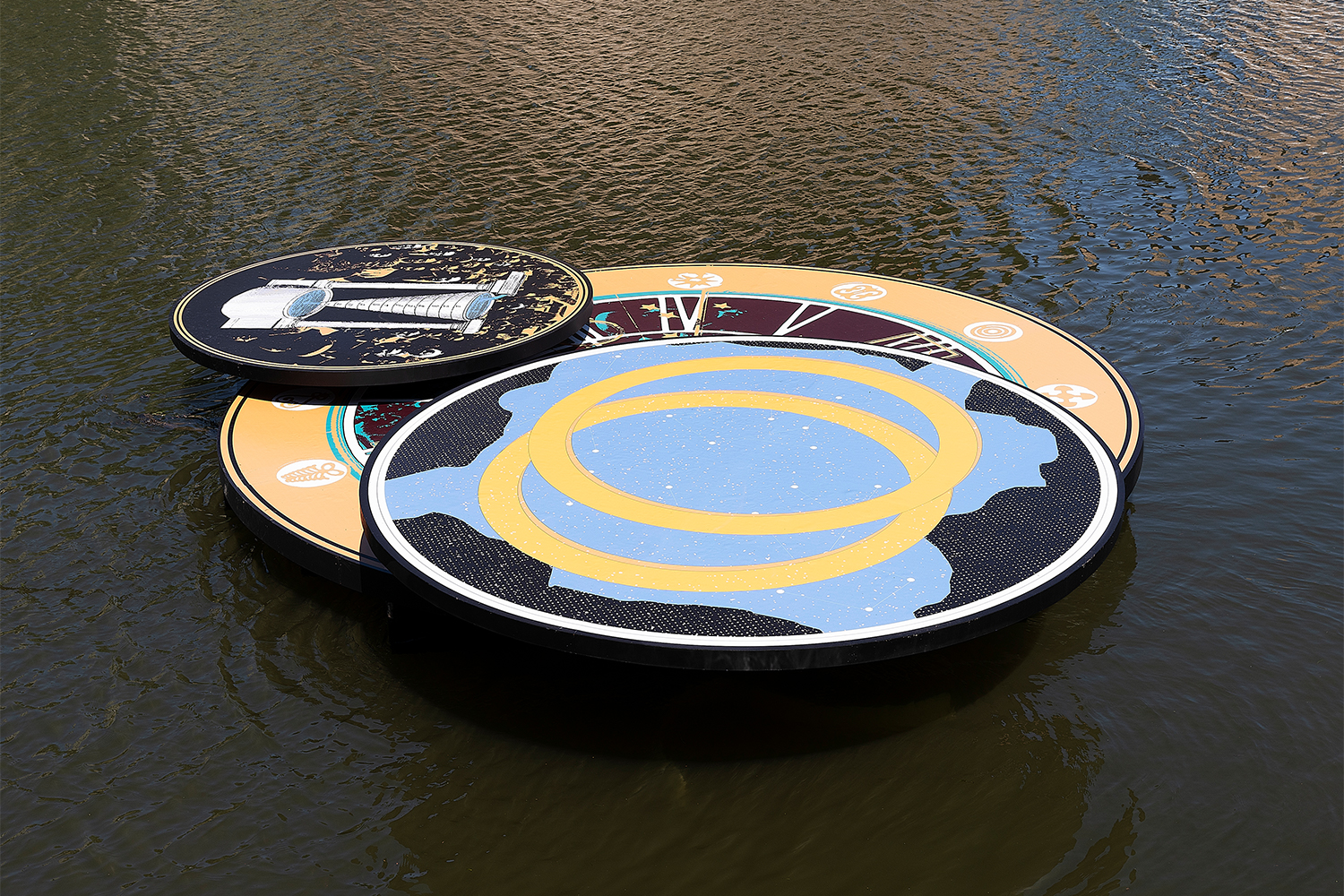

The implied presence of dogs comes from Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon (1977), a significant influence on Gale for this show. In particular, she hones in on the character Circe, a somewhat minor figure in the novel who nonetheless alters the journey of the protagonist, Milkman. Circe is a transfigurer of time: she is from Milkman’s father’s childhood, and appears ancient and withered, yet simultaneously arouses Milkman and transforms his future. When Milkman first encounters her, she is living with an aggressive pack of Weimaraner dogs who are slowly devouring the house she served in all her life. Gale is interested in Circe, but more so in the viewpoint of the dogs, it seems. The blue and yellow lights are informed by the spectrums in which dogs see, and some whistles in the sound work are at a pitch inaudible to humans. Instead, visitors hear the faint crackle of a speaker turning on but appearing to play nothing — a kind of latent suspense.

An accompanying text states that visiting dogs are welcome to drink out of the bowls, which are refreshed regularly. In recent years in London, there have been shows of dogs, by dogs, and for dogs, coinciding with an explosion in dog ownership. For all the questions around domestication of animals and interspecies relationships that Gale’s show raises, it seems to ask a more urgent one, via Morrison: are our institutions in ruins? Rather than leave with Milkman when he finds her, Circe chooses to stay in the house, where her care was essentially captive, to watch it crumble and decay. In situating the viewer within the dog’s senses, Gale invites participation in making ruins of the architecture of captivity.

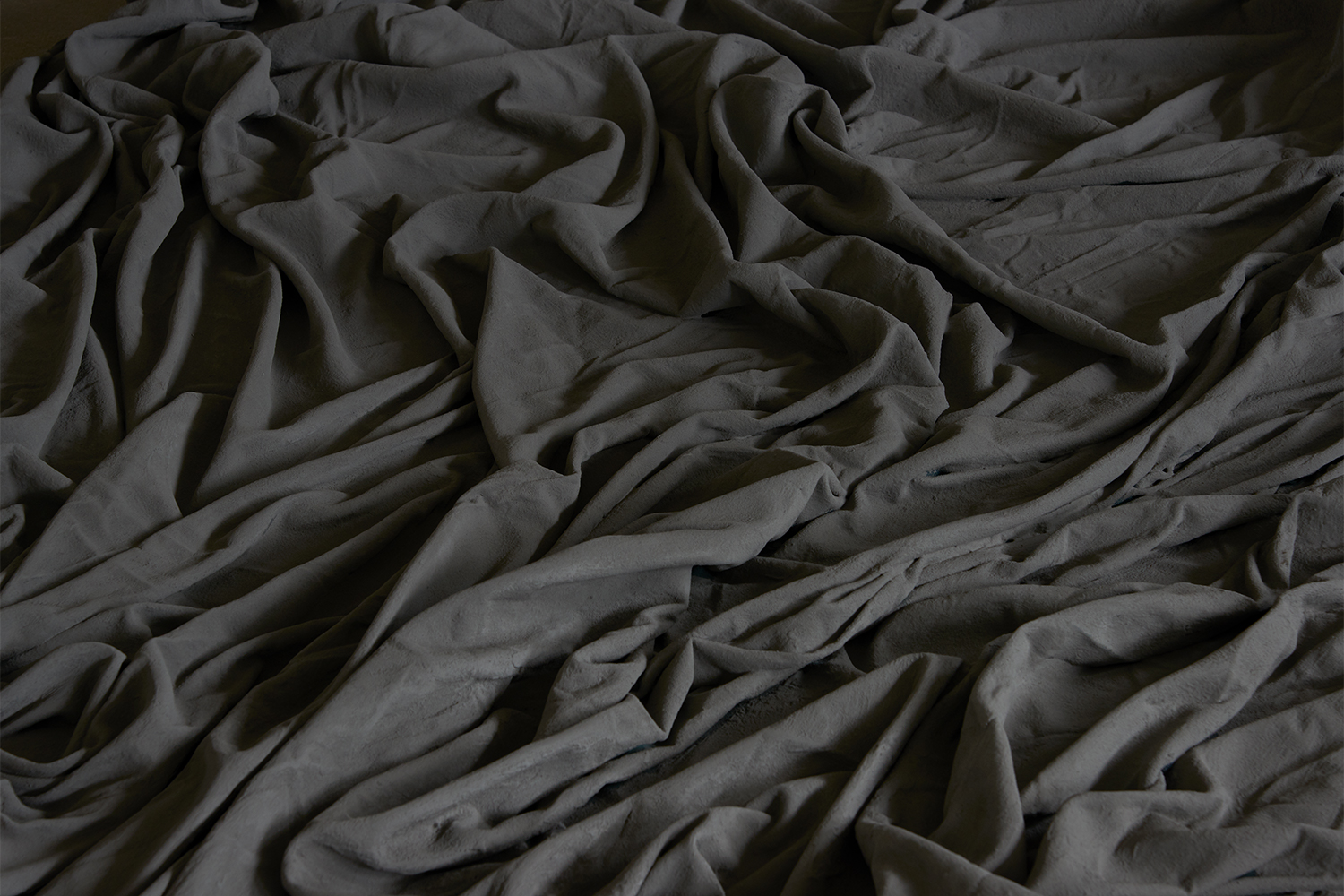

But the show itself is not in ruins (yet). The almost-comedic scale of concrete sculptures — beside the light beams there is also a life-size velvet stage curtain cast in concrete — means that they function as obstacles or hiding places from the pursuing lights. Concrete’s heaviness and implied permanence seems to resist the very idea of ruin, and Gale’s material interest in it comes from its use in barricades, roads, and buildings. Concrete signifies power and violence, as new highways bisect communities of color, and as paved streets heat up cities and no longer soak up rainfall. Gale points to this power’s contingency on institutions: the state, the police, the art gallery. What would it be to resist permanence

and embrace ruin?