Courtesy the artist. ©️ S*an D. Henry-Smith and Flash Art.

Geo Wyex is both hard to characterize and unmistakable when in character, on stage or elsewhere. The New York- born, Netherlands-based artist and musician might best be defined by his deliberate mutability, which allows him to bypass almost any detail that could confirm essential or exclusive aspects of either his person or practice. Through richly evocative performances and installations, as well as frequent collaborations with other artists including AK Burns, Every Ocean Hughes, Colin Self, and Tourmaline, Wyex has crafted a varied oeuvre and gathered key parts of it under Muck Studies Department, an archive and concept that allows him to bridge present tense with history, funk with folk poetics, and choose the terms through which he engages audiences and institutions. This and the rest of Wyex’s work is marked by an intense summoning of feeling that often exhausts itself, luckily always regenerated by the shimmering possibility of intimacy within radically new frameworks.

Isabel Parkes: What is Muck Studies?

Geo Wyex: Muck Studies is a way for me as an artist to encounter black and trans histories in both the landscape I am living and in myself. Muck Studies takes these histories as fugitive, as a series of holes through which things might continually enter a wider field.

IP: What is the Muck Studies Department?

GW: Muck Studies Department is an administrative body that roams around low-lying waterways touching muck and talking about what stinks. It grew out of a need to address a general absence of representation as well as a specific one that reflects my own existence as a trans, Black, mixed-race man. Muck Studies Department plots absence in historical records.

IP: Where did it start?

GW: Muck Studies Department came to being in the Netherlands, which is a place where things are paved over, and history doesn’t announce itself. The Dutch try to cover up loose ends — anything that traces things that have existed outside of the larger institutional order, things enforced by law. I think there’s a way in which the absence I experienced moving here in 2015 from New York reflected the absence of community and friends, so Muck Studies Department marks my reckoning both with Dutch colonialism as well as a personal desire to commune with absence. This is what’s hard about answering the question: there is no heart at the heart! Muck Studies understands the familiarity of absence for many kinds of people.

IP: There’s also a distinctly transatlantic aspect to this conversation.

GW: Right. I think one of the guiding questions of Muck Studies is how do you really unravel the roots of anti-blackness? In America we know it’s alive and well, but living in Europe has helped me understand something about how its roots are consecrated. And that brings me back to the Department, which like all other departments and like many administrative bodies in Holland, is inadequate.

IP: Muck Studies Department is a leaky container.

GW: Exactly. Muck Studies Department is a way to poke fun at the idea of there being any kind of municipal investment in the topic, which is a vague amalgamation of stuff that we can’t separate out. In some ways, trying to do so would be to repeat a kind of a violence that takes place in categorizing, differentiating, and separating, right? Like any kind of exposure or revelation concerning whatever is at the bottom of whatever this muck is would simultaneously be a moment of realizing that neither exposure nor revelation hold any weight.

IP: How does Muck Studies live in the world?

GW: Muck Studies is driven by performance. It possesses a central figure who is intent on doing the wading-work, and often I perform as him. What he can mostly do is narrate what he feels or senses in the present. Often this means poems about gas coming up from the bottom and stinking up the air, or riffs about the idea of the bottom — about touching the bottom — as a practice of liberation. This figure is interested in encounters and in accounting for what cannot be accounted for. For example, the violence of anti-blackness cannot be accounted for because it’s so vast; it touches everything — like history, it is immanent. But, that doesn’t mean we are fucked; it means that all we have are each other. And it means just as anything can decompose, anti-blackness can also rot. There is life beyond, after and before anti-blackness. People encounter liberation in all manners of violent systems.

IP: What does performance allow you to do?

GW: Performance allows me to communicate a web of ideas in the most direct way possible. I’m resistant to let Muck Studies settle and become a known form, which can make it a hard project to book and to present, but performance certainly offers moments in which my core ideas take shape.

IP: Can you say more about your background as a performer?

GW: I’ve always been a performer and a musician who played piano, composed, and sang. I performed a bunch in the early and mid-2000s in New York, alongside a slew of Cabaret and alt-drag performers, which is really the community I feel closest to. I think it’s a different time now, but back then, queer folks and weirdos were more — and I use this word non-pejoratively — ghettoized. We were separated from the mainstream; we performed in bars. That’s my family and my background, the place from which I began to expand my music and develop characters through things like costume changes on stage. I was really inspired by people like The Blow, contemporaries like Colin Self, and by experimental, feminist theater in New York from the ’80s and ’90s, people like Peggy Shaw and Split Britches, as well as black feminist innovators of poetic and theatrical forms, like Adrienne Kennedy and Ntozake Shange. Also Coco Fusco, Jack Smith, and Pope.L, those who move through visual arts in a performative, radical way.

IP: I’m glad to hear you bring up costume changes as a way to develop character, because I also think of your practice as having a vividly material and multisensory quality to it.

GW: It’s taken quite a while for me to understand my relationship to objects and object making, I think because I was just a performer for a long time. I started by messing around with making different kinds of eyeglasses, things to alter my field of vision. Getting into an altered state has long been important to me, and I don’t mean through drugs or alcohol. I get so nervous before I perform that I do not need anything. I’m fully high on being petrified. I think the glasses were my entrance into another realm of character.

I remember first bringing lights with me on stage, too, so that I could also do lighting changes myself, even in a basic downtown piano bar. I’m talking about small things that make a big difference, about understanding how shifts within performance have to do with shifting expectations. I’m aware of an object’s ability, especially alongside performance, to help dislodge something. I rapidly became more and more interested in pursuing that dislodging as a format for performance, and not necessarily to scare people or anything, but to move something. I think there’s a lot that we as performers are entrusted to do in terms of taking care of an audience, and the audience doesn’t always take care of the performer. That kind of negotiation, which I feel took place while I was in my early twenties, became a big part of how I would use objects to shift my own and my audience members’ expectations. Objects contain a lot of energy, which means often they can generate a lot of focus as or on a performer. In Muck Studies, objects are often used as evidence, and for what, it is unclear. Once in a while, I’ll take an object that I’ve tried to collect in relationship to Muck Studies itself and then try to turn it into something visually interesting, and I fail every time!

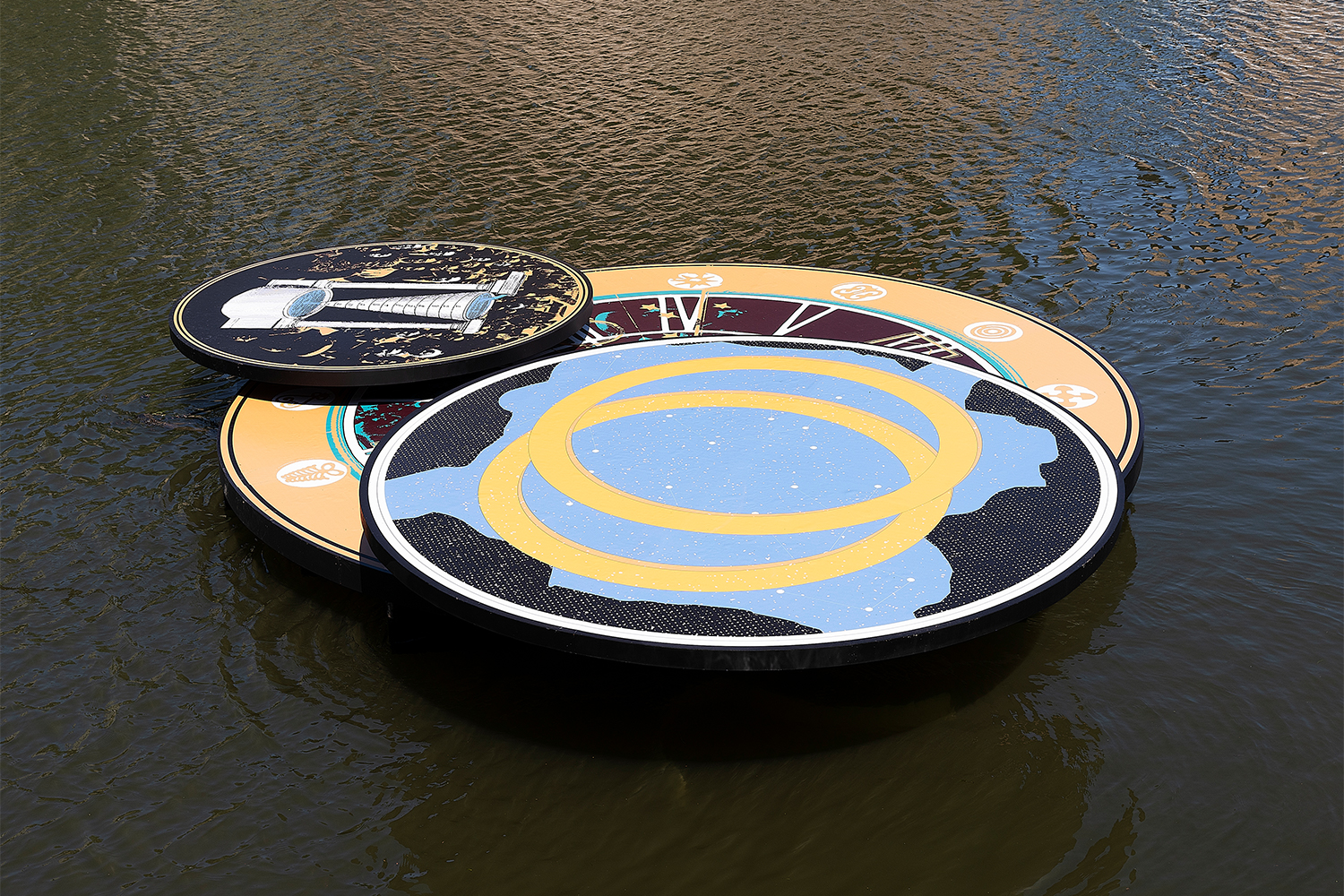

IP: Is that true, though? What about your van project, Muck Studies Dept Archive-That- Matters (ATM), (2021)?

GW: Okay you’re right, but I had a lot of help from people there! I think what I mean is there’s a way in which Muck Studies still hasn’t found its objects, or maybe it has and they’re loose.

IP: Does that make them less of an object? I’m thinking of how you’ve used change and coins, for example.

GW: When I say “loose” I’m describing the performative capacity of objects: their relational power and ability to communicate emotion, history, and spirituality, rather than objects that might have a particular mode of display. The coins I use function through touch, through playing them like an instrument. I’m in conversation with the material. Often, performances associated with Muck Studies Department are staged encounters that the main character is having with objects such as these, that are indicators of real life but that also allude to things that are not visible, things that you cannot always see or count in a measurable way, like value. [pauses] I’m interested in mood and in value.

IP: Hard to represent.

GW: It’s tricky to figure it out, and that’s part of

the work. There’s a lack of language, and I’m interested in that lack. Is that what is liberating about representation?

IP: What kind of representation?

GW: Right, it all depends on where. Let’s say in a mainstream TV show. Some might make me feel good, if I see myself or some aspect of myself represented, and that’s cool. But more often I find myself asking about other ways of encountering, let’s say, textures of Black or trans experience. Representation today tends to freeze things and make them feel static, even though we live in this fast world, where constantly we want more. A lot of the things I see represented about the worlds I’m connected to make me ask who is being actualized. Who is being helped by this image? At the same time, I love how visual representation can make me feel. I loved seeing Nicole Eisenman’s fountain in Munster, Germany (Sketch for a Fountain, 2017), a few years ago. I cried when I saw her sculpture of a nonbinary person peeing. I am moved by representation — I make theater! But I’m curious to explore different ways of encountering things that are less visible, not through representing them, but through acknowledgement and through response, through tacit exchange.

IP: Does this connect to the personal aspects of Muck Studies that you mentioned earlier?

GW: For a long time, I found it difficult to represent myself visually, so perhaps that’s why I’m curious about other ways to do so, and to other ends. I find I’m less drawn to looking at things than I am to listening to them. Maybe it’s a personal thing, which means there is certainly a politics to it. The big investigation for me as a person and as a maker is thinking through how to cultivate sensation: how to cultivate something that extends beyond the visual, how to make mood happen, amidst it all.