“Structures for Life,” a beguiling survey of the still vibrant and radical work of Niki de Saint Phalle conjured from more than two hundred objects and artifacts, including sculptures, works on paper, films, and ephemera, is surprisingly the first ever museum exhibition dedicated to her work in New York, and by far the largest American exhibition for this artist in recent memory. Certainly de Saint Phalle never quite attained the same recognition or reputation in the States as she enjoyed in her native France or Europe, but in many ways it has been the nature of her vision and practice that have made it difficult for the art establishment to appreciate her singularly eccentric oeuvre, both within her lifetime and posthumously. Working with a boldly feminine iconography prior to the rise of feminist art, and doing so in a visual language that would continue to lie outside of feminist perspectives, all the while leveraging a sometimes angry and always confrontational opposition to societal patriarchies, her abiding idiosyncrasy seems bound to misfit the polemics of the very same progressive politics that should otherwise contextualize her art. For all that may be problematic in this, however, you cannot help leaving this immersive journey into her life and art without a greater sense that it was Niki’s boundless sense of joy and ecstatic embrace of pleasure in her art that has made her too subversive to the avant-garde aesthetics and ideological precepts that might have otherwise sustained a more serious appreciation of her art.

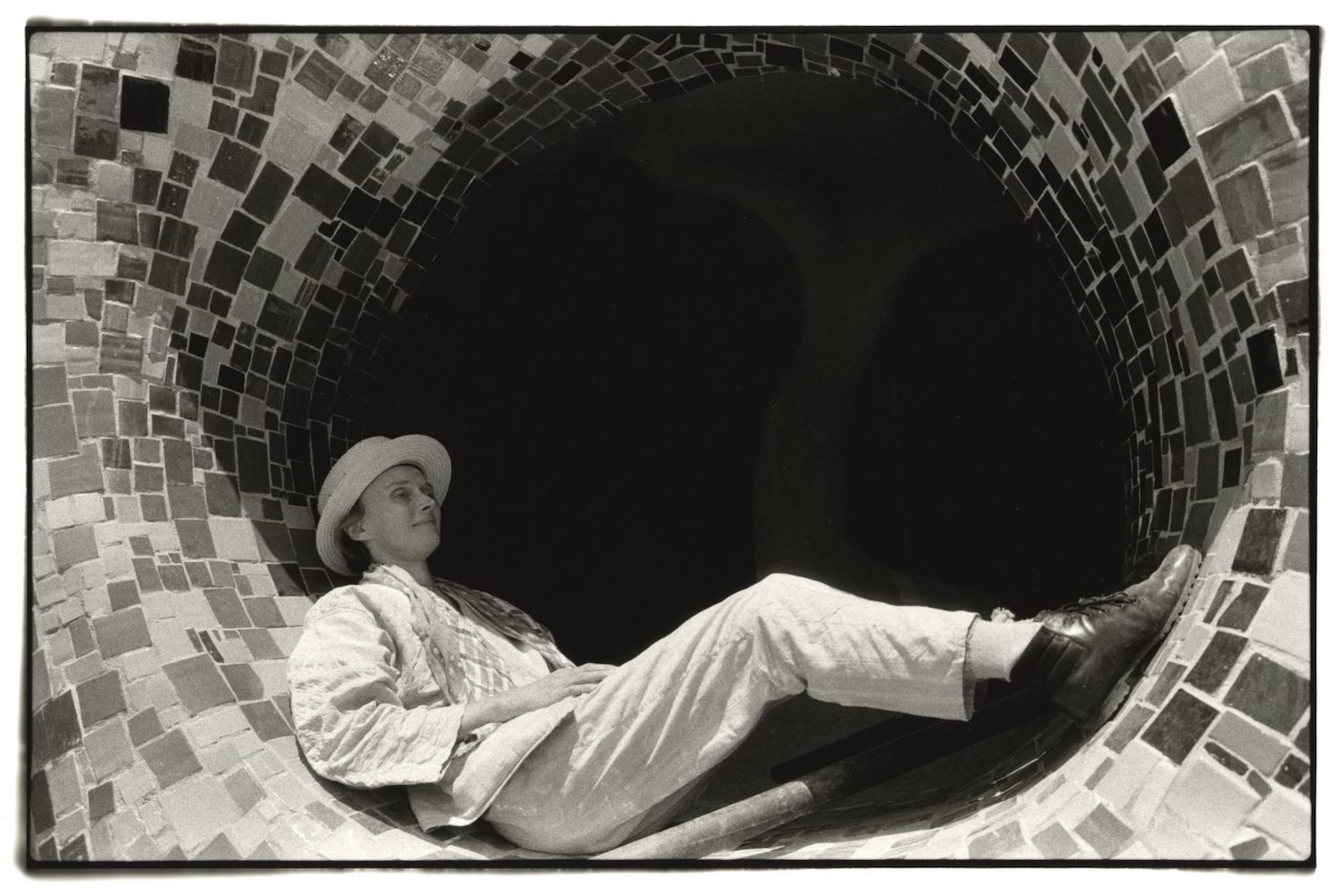

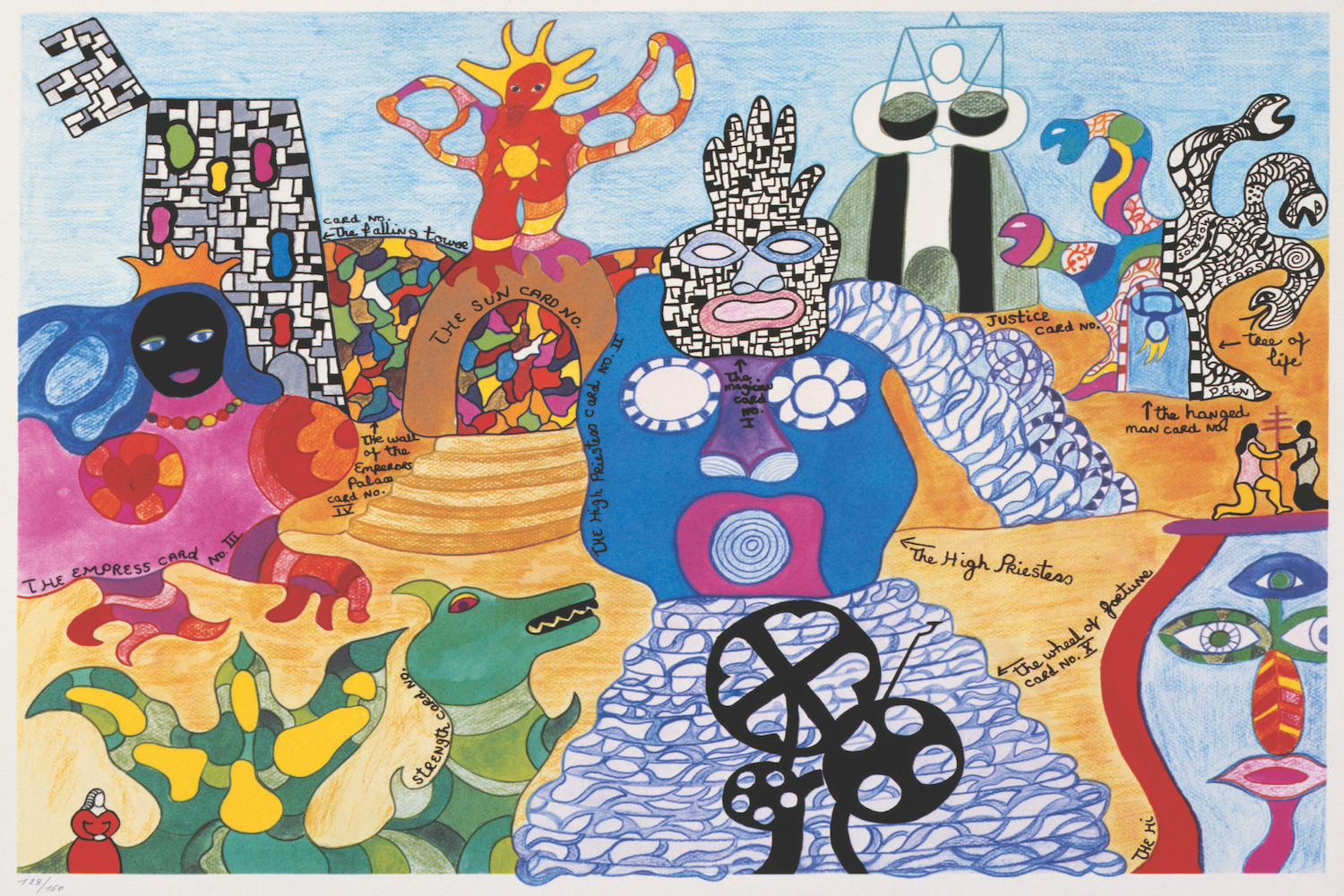

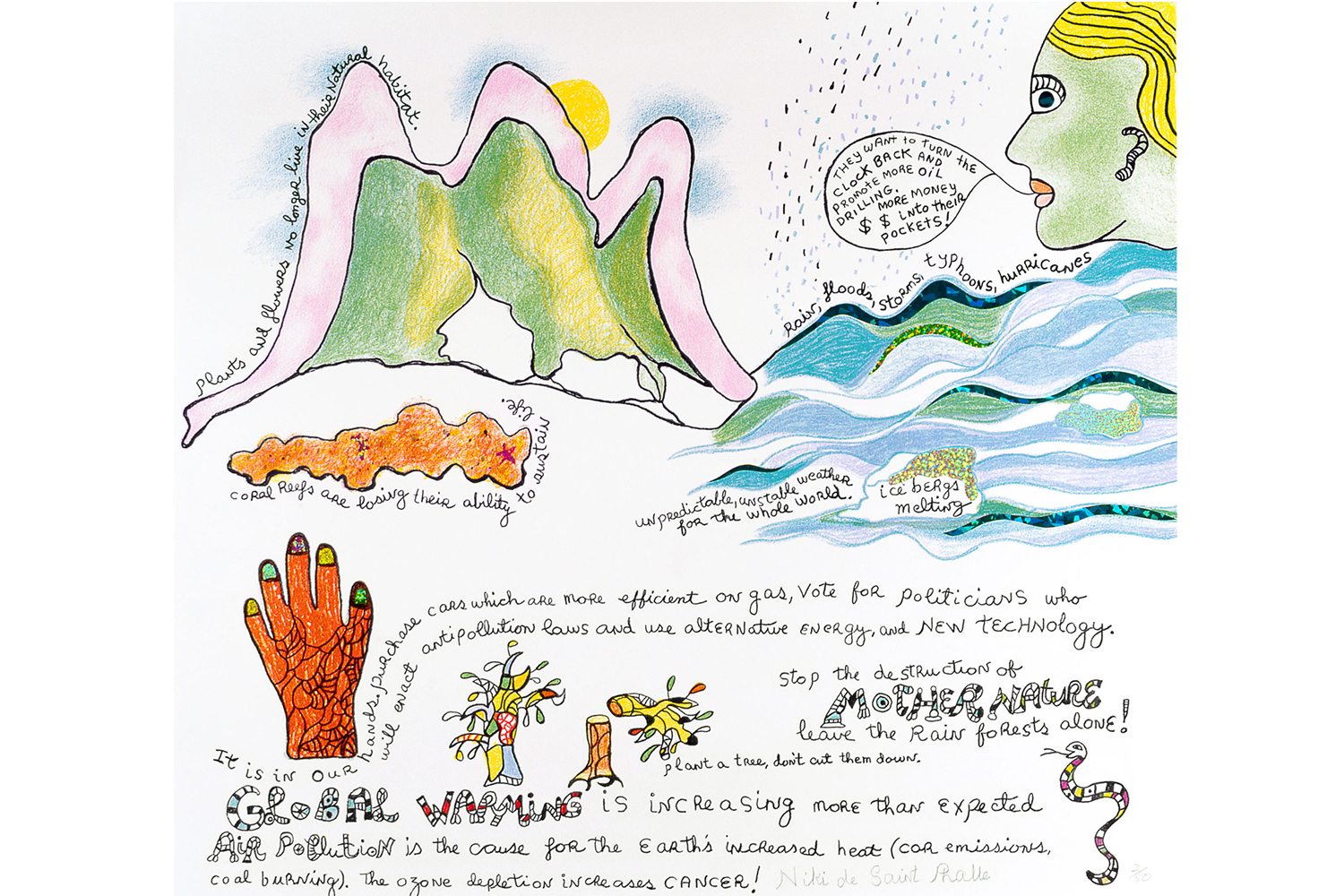

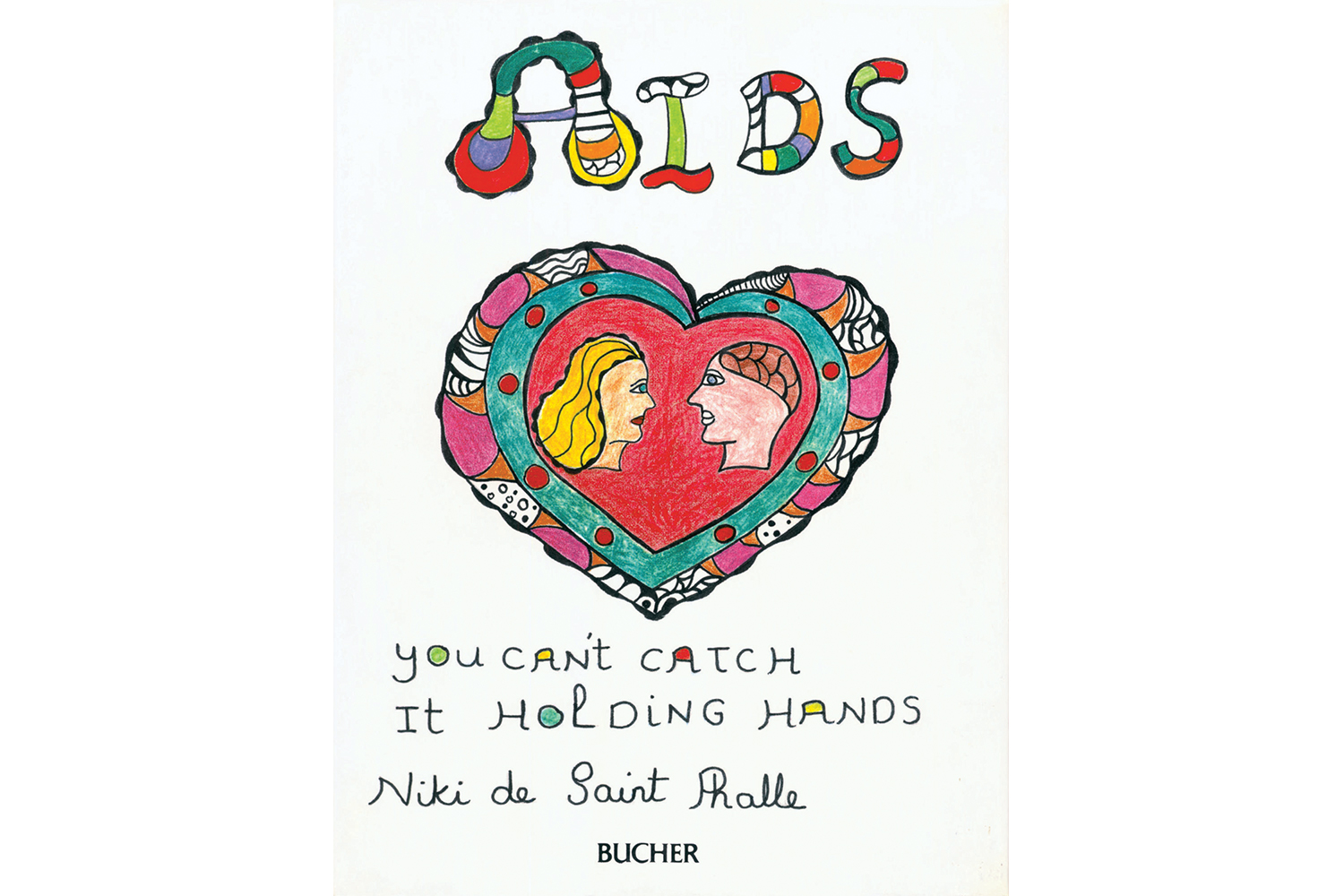

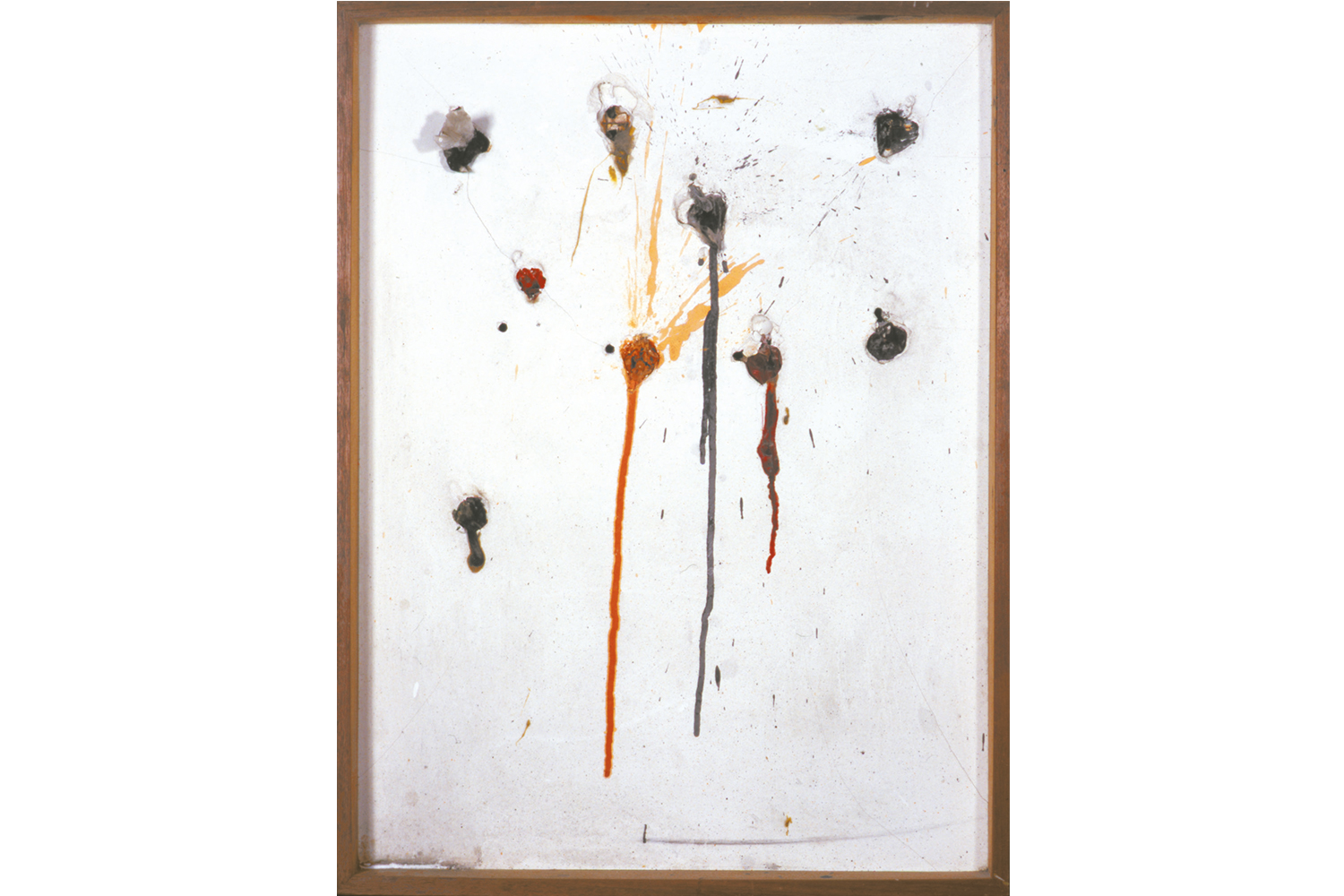

Is it the abiding sense of pain and trauma she sometimes confesses, but more often leaves lurking there like unspoken shadows in her sunny fantasies, that is just too uncomfortable? Or is it rather a wildly unpredictable and informal sense of child’s play all too lacking in the gravitas expected of fine art that simply kept her from being taken seriously? Each in its way is a direct response to the sexual abuse she suffered as a child at the hands of her father, the objectification she felt as a stunningly beautiful and successful model in her teenage years, and her growing awareness of society’s entrenched oppressive injustices that would culminate for her, as for so many others, in the social upheavals of 1968. In allowing for a more comprehensive chronology of her work — ranging from some stunning examples of her “Tirs” from the early 1960s, in which she shot a gun at assemblage paintings containing embedded balloons of paint that would explode in lurid eruptions of color, to enrapturing documentation of her utopian pleasure parks and playgrounds and some of the commercial products she produced to fund her ambitious public art outside the usual trappings of institutional, municipal, corporate, or individual patronage — viewers are gently guided through one of the most remarkable transformations in any artist’s lifetime. Here we see how a mass of suffering, frustration, and anger can be transmuted into an art of irrepressible joy and optimism: perhaps the most valuable lesson her work can give us today.

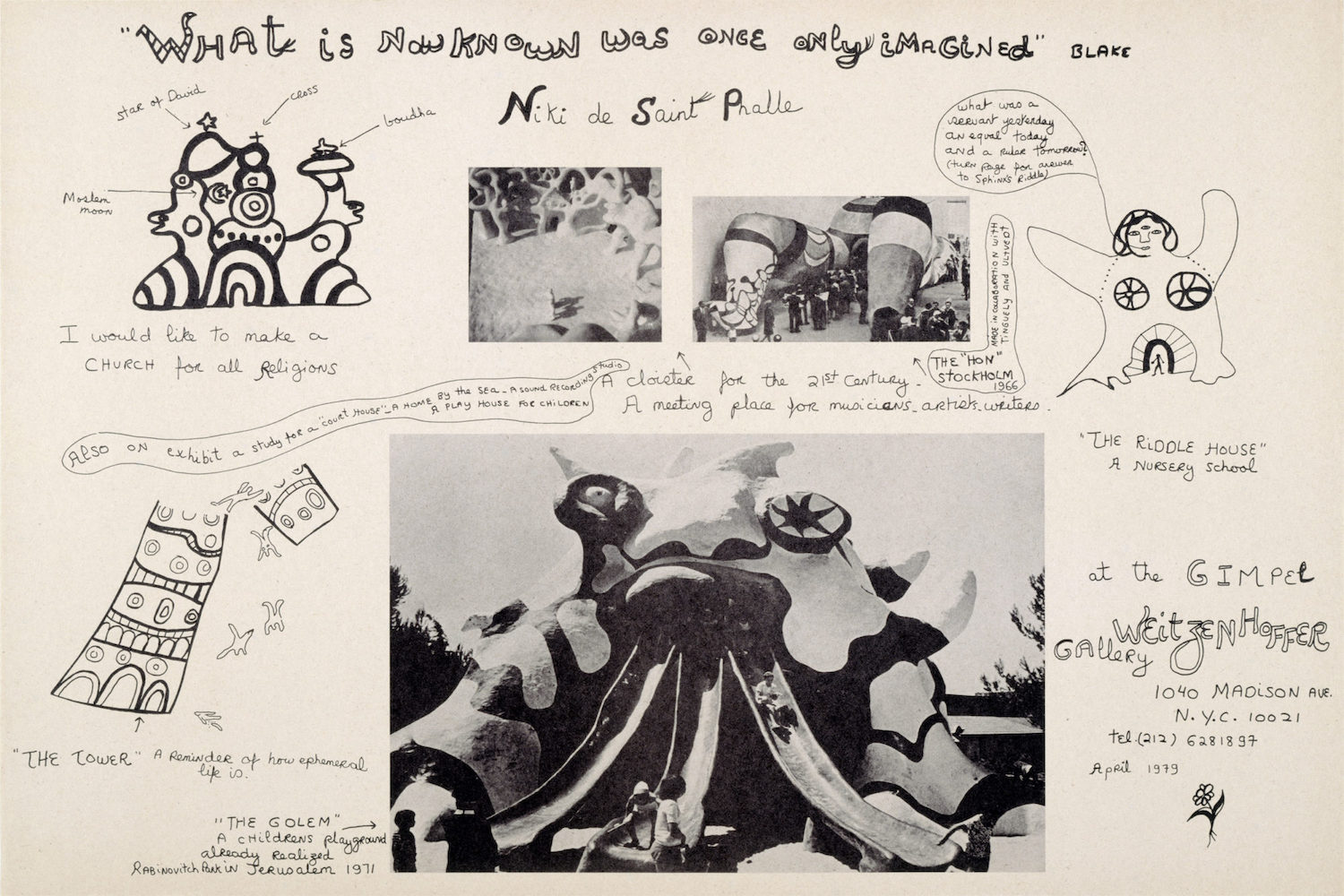

If Niki de Saint Phalle’s idealist politics and confrontation with patriarchal hegemony sets her at odds with many, it is her unabashed populism that truly remains provocative to the standards of fine art. Her public art, much of it done in collaboration with her then husband the Dadaist-infused Swiss kinetic sculptor Jean Tinguely, engaged just about everyone except those very gatekeepers whose abiding hierarchies between high and low remain essential to cultural ratification. Arriving at a time when public sculpture was still predominated by an endless succession of war memorials, fast-forgettable male civic leaders, and anonymously idealized allegorical female statuary, de Saint Phalle’s erotic and exotic organic feminine Nana figures, brazenly voluptuous and emblazoned with riotous colors and eye-popping patterns, not only contradicted norms of subject and taste, but they invited kids of all ages to romp about them. As a little kid who knew nothing of this artist but encountered the first of her massive public enchantments, “Le Paradis Fantastique,” first at Montreal Expo 67 and then in New York City’s Central Park in 1968, at the psychedelic apogee of my town’s difficult urban trip, it was revelatory to find out many years later how she actually meant to bring her art directly to the people, to make something that kids could play on. In a time now when installations have come to embody a new mode of experiential art, and conceptual figures like Yayoi Kusama and James Turrell have found massive popularity with people who might otherwise never venture into a gallery or museum, there is no understating her prescience.

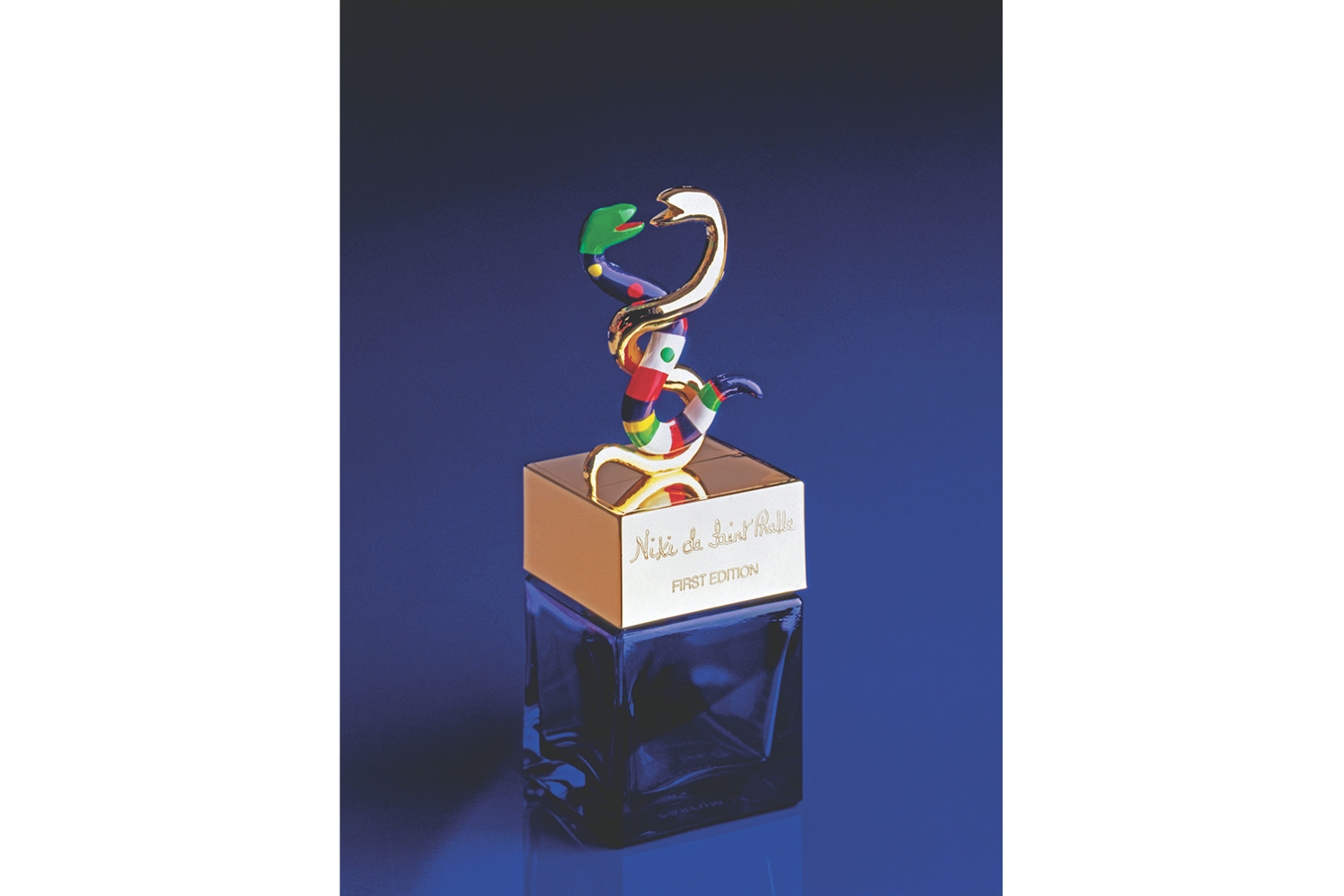

Curiously, it was de Saint Phalle’s most populist tendency, to create a mass of affordable and accessible products, that remains under-recognized. From her participation in Daniel Spoerri’s seminal Edition MAT, in which the idea of an art form that is at once multiple and original was first codified in the wake of Duchamp’s ready-mades, to an ongoing series of her own products beginning with inflatable Nana beach toys in 1967, running through a line of jewelry starting in 1977 and a perfume line in 1982, and including the production of vases, T-shirts, lamps, stickers, wallpaper, and bath gel, it is easy to see how the very sensibilities that made her so suspect to refined tastes would earn the admiration of artist like Andy Warhol and Keith Haring. Today, in the ongoing convergence of visual culture in which paintings and products continue to acquire a relative equivalence, it is perhaps the thorniness of Niki de Saint Phalle’s explicit commercialism, long before the mass popularity of Murakami, Koons, or Kaws, that stands out among her many vital legacies.