During the 1950s the contemporary art world lived in a season of art informel that lent itself to curious and entertaining experiments, like that of the monkey, author of the famous informel ‘works’ — not that dissimilar to those of certain ‘artists’ — exhibited at London’s Tate and placed in auction at Sotheby’s. Yet in precisely those years, there were others who traveled around the world and escaped from these general tendencies. This was a group of young artists that operated in surprisingly distant places from one another, in small cities like Ulm, Cholet, Padua or Udine, to grand metropolises like Paris, Vienna, Milan and Düsseldorf, in Latin America and the Soviet block. Some of these artists came from more than just disparate places, but also from diverse formative and cultural experiences. Another unique feature of this group was their lack of awareness of each other’s existence, because, as a movement in the making, no historian or critic had yet to theorize their work. However when various circumstances allowed for their meeting, these artists recognized themselves as subjects of a common sentiment, as more orientated towards design and architecture, sociology or psychology than to individual artistic poetics. At hand was a kind of spontaneous germination that envisioned young people from disparate areas of study and various professions working together. From that point on they formed groups centered upon collective working. Many were completely new to the field of art and only a small minority came from art academies.

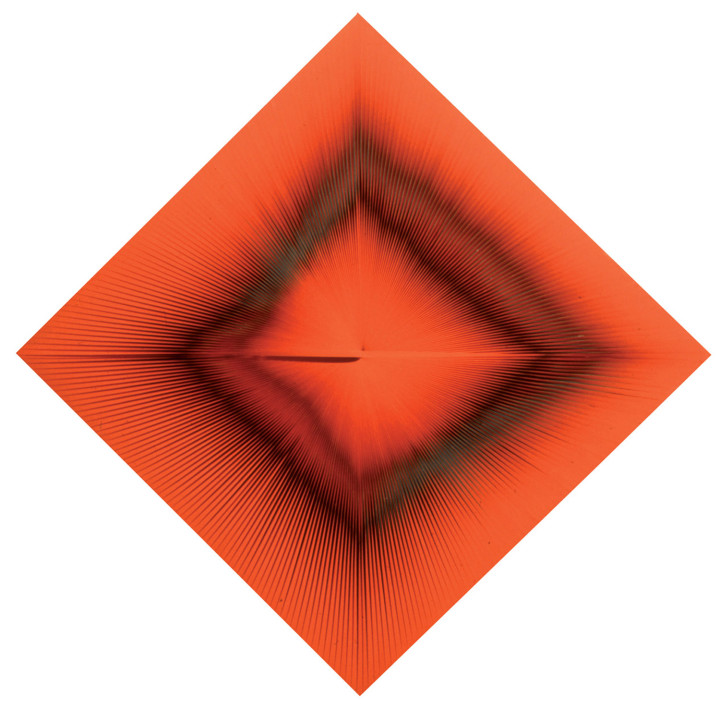

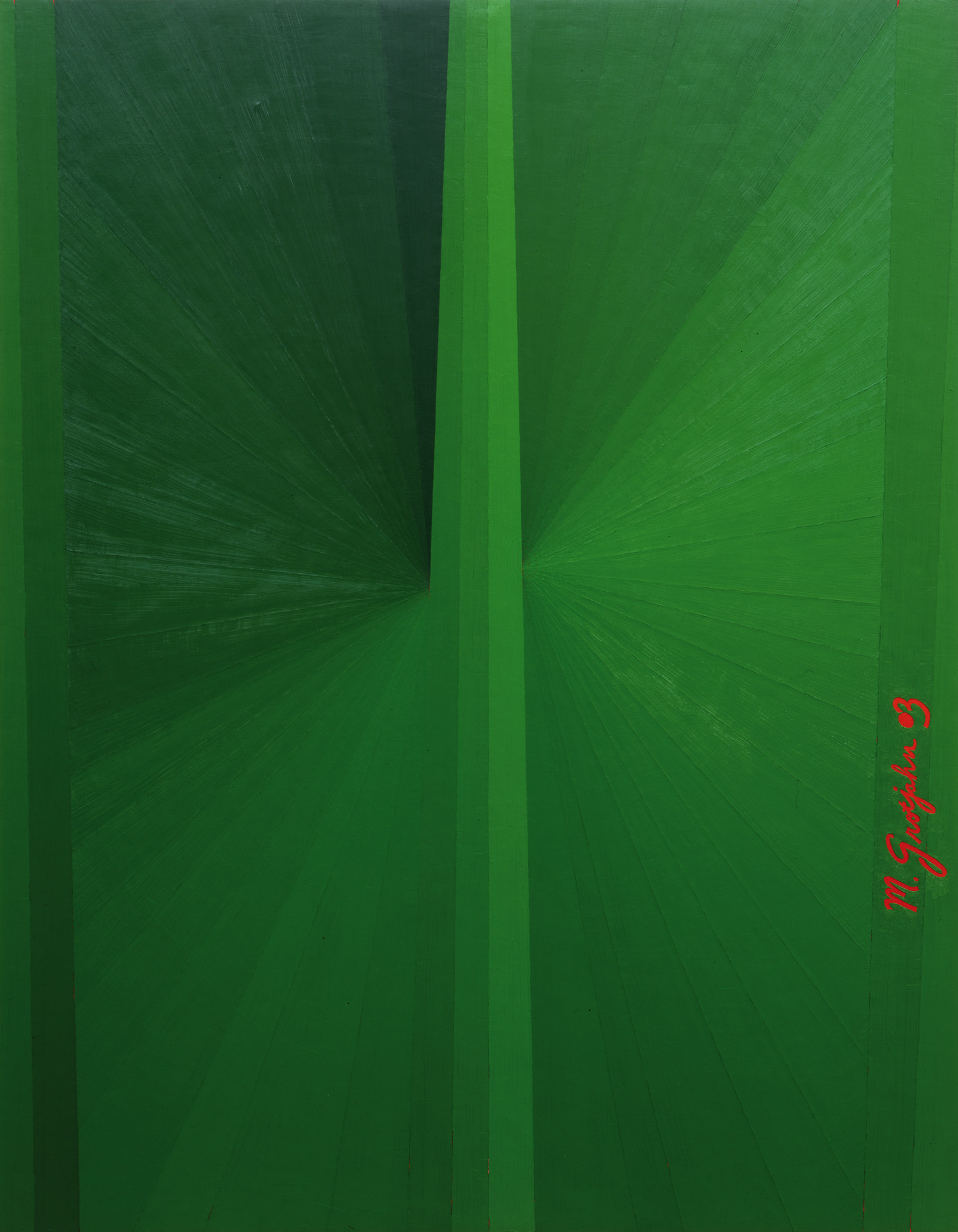

We worked — with diligence and without the desire for fame — on optical problems, perception, virtual images, the intrinsic dynamism of the work, the intervention of the spectator, on light and space, on seriality, new materials and on an unseen presentation of what was known, with mathematics and exact forms as a base. All of this was conducted with a new spirit, with a rationality and logic that promoted new operative modes, different expressive possibilities and all those elaborated phenomena, ideologies and psychologies relative to the problems of the visual and the optical. These were needs that addressed the human conscious, yet with a research approach closer to science. We wanted to give art a scientific meaning and consequently a social dimension. This was an art based on objectivity, free from any literal interpretation, art as a proposition and resolution of plastic problems that were always verifiable. This was an art that amplified the field of knowledge, maintaining a strong didactic component.

At the time, interpersonal information was scarce: telephone calls were difficult to make and certainly not quick, nor were they available to all; periodicals rarely dealt with art and those few specialized magazines were dedicated more to antique or historicized art. So what of the documenting of current topics, or our research? Nothing! This did not favor the sharing of knowledge, nor did it foster facile plagiarism, and what was being made was always original. We worked, therefore, in darkness (in metaphorical darkness of course), yet, ironically enough, much of our research regarded light and its phenomenology: light as material, and never as a metaphor of light.

I hope to have explained how the world and its possibilities were around us just under fifty years ago, a time quite different from today, where everything is known and comes to everyone’s door the moment it is created, allowing everyone, from one continent to the next, to be informed, assimilate and emulate.

In his native land, the young Brazilian artist Almir da Silva Mavignier, like others in South America, heard of Georges Vantongerloo, Josef Albers, Max Bill, Alexander Calder, artists who traveled to countries like Argentina, Venezuela, Chile and Brazil, to discover new worlds or to disseminate new ideas. Mavignier won a scholarship to the new Ulm School, modeled after Bauhaus principles and founded by Max Bill, and began to travel through Europe where he encountered those who worked with his same ideas, yet with different intentions and results —vastly different because originality was one of the basic prerogatives of our work. Mavignier found young people like himself, such as Marc Adrian in Austria; Paul Talman, Karl Gerstner, Andreas Christen, Marcel Wyss in Switzerland; Rudolf Kämmer, Uli Pohl, Herbert Oehm, Gotthartd Müller, Gerard von Graevenitz, Dieter Roth and Walter Zeheringer in Germany (where in Düsseldorf Einz Mack, Otto Piene and Günther Uecker would later establish the Zero Group); Piero Dorazio in Rome; Enrico Castellani and Piero Manzoni in Milan; the already well-known Gruppo N in Padua with Manfredo Massironi, Toni Costa, Edoardo Landi, Alberto Biasi and Ennio Chiggio, whose ideology was based on anonymity of the work; Julio Le Parc, François Morellet and Joël Stein in France; and Ivan Picelj and Julije Knifer in Zagreb.

It was in Zagreb where the Exat 51 group was based — in a country that at the time wasn’t easy to reach, but whose ideas were similar to our own. More precisely, our outlook was much closer to that of Eastern Europe and Mitteleuropa. Almir Mavignier found Bozo Beck (then director of the Galerija Suvremene Umjetnosti), Kelemen, Mestrovic, Picelj and Putar with which he organized an exhibition of artists who shared similar ideas and a collective constructive rigor.

In 1961 the first “Nove Tendencije” exhibition was launched (from which followed four others) and during its inauguration I was holding my first solo exhibition in Ljubljana, a few kilometers from Zagreb, thanks to Zoran Krinsnik (then director of Moderna Galerija). At the time I was working for an engineering and architecture studio and as a graphic designer for an electric materials manufacturer near Milan. I was living in Udine, a short distance from Padua where Gruppo N was based, but I did not know of their existence, not to mention their research. When I went to the exhibition in Zagreb, I discovered our many common practices and I immediately entered into the New Tendency group, participating in all of the subsequent exhibitions.

Another important element of this ‘new tendency’ was the total self-management of the artists: the exhibitions were organized by whomever was producing the work, right from the artists, without critics or mediators. Our way of working was severe and rigorous, allowing only the entrance of research that had characteristics which identified with our own objectives. It was in Zagreb, in March 1962, at the Galerija Suvremene Umjetnosti where I would present my second and larger solo show.

The New Tendency system was innovative: not a cult of personality (at times even anonymous); not commercialization; not private galleries (but only cultural institutions); not elitist art; not fetishism; not unique works (but the beginning of multiples with a social purpose); not interpretation; not metaphor; not mystification; not strategies; not all the things that we felt were wrong with art and for which we did not want to make the same errors. It was for this reason, this ‘zeroing’ of many of the old artistic values, that many exhibitions were called “Null” or “Zero,” especially in northern Europe where things were more radical. The first few years were pioneering ones, filled with projects and ideas for a near future, a future made of discoveries that gave energy for further research, or even better — a future that could make us believe that the world would see something indicative in us to take as an example. And we, in turn, saw the world in a dynamic perspective for a total social and cultural evolution and lived through the principles and parameters of this innovative art.

Exhibitions were born of an art envisaged by artists like Bruno Munari, and from semiologists like Umberto Eco who in 1962 was theorizing the opera aperta. There were other New Tendency exhibitions at the Palazzo Querini Stampalia in Venice, at the Musée d’Arts Decoratives Palais du Louvre in Paris, and at the Städtische Museum Schloss Morsbroich in Leverkusen. International exhibition titles included: “Arte Cinetica,” “Le mouvement,” “Visualità,” “Lo spazio dell’immagine,” “Environments,” “Light,” “Monochrome,” “Nuove tecniche, nuovi materiali,” “Recherches continuelles.” In 1965, the Museum of Modern Art in New York presented “The Responsive Eye,” an exhibition initiated several years before by William Seitz, that united artists suggested by other artists, but with criteria dissimilar from New Tendency. That exhibition summoned the great success of Op Art, as it was called by the American media. In the fashionable windows of Fifth Avenue, there were enlarged photographs of our work. Major magazines and newspapers published images of our most spectacular work — of our most famous artists! Success, success, success, for this phenomenon of a pure aesthetic plane, of surface. But it was all absolutely contrary to our prerogatives. This was the real tragedy — its consumption and its end: the misunderstanding of our ideology. Our artistic license was robbed, sacked. Everyone utilized our images and misused and contorted our research, vulgarizing everything and debasing its significance, taking away the vital energy that each one of us reflected in our research.

As far as I am concerned, this research does not have to be conditioned by fashion or the market; rather, it has, and will certainly continue to have, an autonomous life, a life as long as that of sight and of vision.