Is Nancy Holt primarily a land artist? The notion of Land art conjures a time generations ago when landscape was considered an empty canvas to be filled on a gigantic scale without consideration for post-colonialism. However, Land art helped define the concepts of site and non-site, as well as site-specificity, particularly through the writings of Robert Smithson, Nancy Holt’s superstar partner. Today, one can discern subtleties in Holt’s works, showcased at Gropius Bau, in her largest exhibition to date in Germany. It begins with her single-page concrete poems from the early ’60s, which already reveal an inner dialogue on individual perspective and framing. A series of typed pages — a written version of The World Through a Circle (ca. 1970) — reads “Elements real and reflected / Concentrated, encompassed…”

Formally, it’s a small leap from there to the artist’s written and recorded audio tours, which invite viewers on highly focused inspections of different sites. Stone Ruin Tour 1 (1967) guides participants through an overgrown brick foundation in the New Jersey woods. In Tour of the John Weber Gallery (1972), the artist pays as much attention to stains and cracks in the walls as to the displayed art or the view through the window. The distanced, matter-of-fact audio narration presents a subtle sense of self-deprecating humor with refreshingly subversive potential, also tangible in her Locators (1970–71), small constructions of metal tubes, to be used like fixed, lensless cameras focused on seemingly banal details outside the studio or gallery window. By shaping the gaze itself, both the viewer and the view, these sculptures create space for an open-ended exchange on perspective, point of view, and perception.

“Circles of Light” also presents works featuring actual conversations, such as a voice recording of the late artist Richard Serra and the theorist Lucy Lippard, engaged in a critical discourse on video art and media culture. This conversation is featured on one of four video monitors that make up Points of View (1974), arranged on four sides of a white box, mirroring those of the original exhibition space, the Clocktower in New York, where the screens were positioned at the four cardinal points.

Another legendary exchange showcased here involves Smithson and Holt in East Coast/West Coast (1969), in which the pair can be seen in Joan Jonas’s studio, experimenting with video technology as they spontaneously create a comedic skit. They playfully embody stereotypical behaviors of artists from New York (insistent on theory and concepts) and California (laid-back and instinct-driven). This seemingly pretentious display of amateurish acting ensures that informed viewers understand the joke. A similar sense of humor is evident in some of Holt’s serial photo works from the same period, such as Miami Puddles (1969), which foregrounds landscape through the ephemeral and trivial phenomena the title suggests.

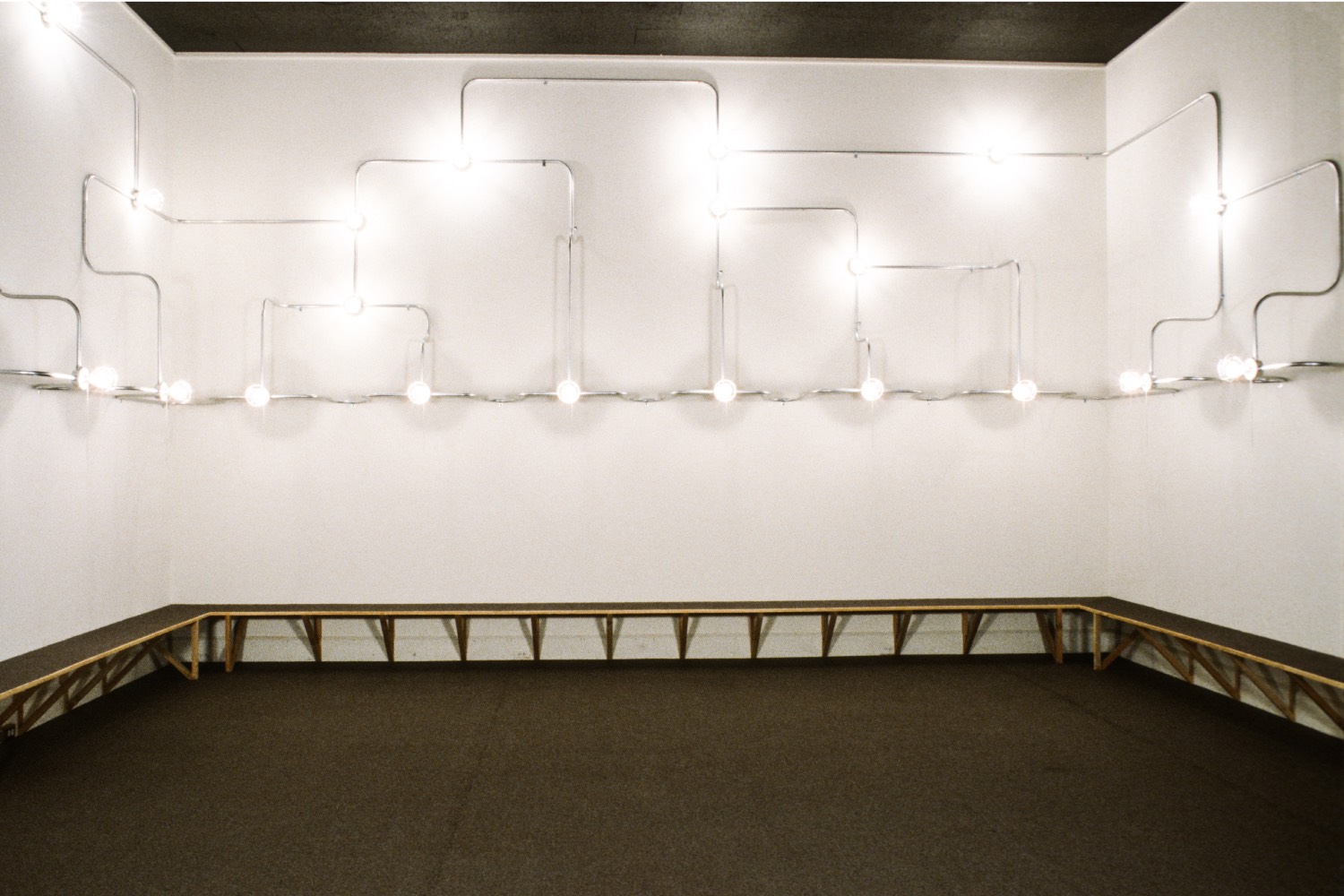

This humor contrasts starkly with the pathos of the illuminated grandeur of Electrical System (1982), an installation that occupies the entire gilded Jugendstil atrium of Gropius Bau. It consists of an intricate network of metal conduits and light bulbs, supposedly highlighting the machinery that makes art visible and revealing hidden structures. Perhaps I am missing the joke here, but in the era of free Wi-Fi, wireless charging and electric cars, the idea of electricity being invisible feels as out of touch as the Christmas atmosphere it evokes in springtime.

The artist’s most famous work is presented in a large space of its own. A twenty-six-minute film shows the construction of Sun Tunnels (1973–76), capturing the process from the production of the four enormous concrete cylinders to the meticulous preparation of their bases and precise placement. Arranged in an “X” formation, the tunnels are perforated with several holes in patterns based on four distinct stellar configurations. As a result, sunlight filters through them in various ways throughout the year, suggesting that this work not only leaves its mark on the desert but also invites reflections on the planetary and cosmic dimensions of space and time. It’s hard today not to perceive the work within the context of grief for a lost loved one.

In Mono Lake (recorded in 1968; edited in 2004), the artist, her husband, and their friend Michael Heizer explore a bizarre landscape along the shore of a saline lake. Their encounters with alkali flies in the water and encrusted rock formations are captured along with the paraphernalia of the journey: the car, beer cans, blue jeans, and cowboy boots. Accompanied by a soundtrack featuring random facts about the lake, interspersed by borrowed country and film music, the charm of this home movie lies not so much in its educational value but in its Super-8 aesthetic and portrayal of the artists in a state of becoming the mythical, larger-than-life figures they would later embody — far removed from the tragic plane crash that killed Smithson five years later.

Holt took over the management of Smithson’s archive, thus playing her part in ensuring his enduring fame. Notably, she donated his Spiral Jetty (1970) to the Dia Art Foundation in 1999. It’s therefore not a surprise that Smithson occupies a prominent space in this exhibition. However, refreshingly, he’s portrayed as simply a young artist engaged in collaborative projects marked by startling playfulness. This perspective, in retrospect and for this reviewer, renders the monumental projects of Land art less pompous. It is within this dialogue of poetic and physical exploration of the site and its constituents that this show has its most significant merits. Apart from presenting Nancy Holt as an equally curious and generous artist — witty, confident yet willing to challenge herself — the exhibition showcases her rare ability to create environments that generate questions.