A few days prior to New York Fashion Week last September, I came across an article in The New Yorker magazine that examined the creation of cult fashion label Hood By Air, which has become mainstream fashion’s latest obsession. Under the title “Hood by Air’s Radically Aggressive Streetwear,” the magazine’s Annals of Fashion section told the story of how the brand’s founder, Shayne Oliver, turned a small number of social outliers into a global phenomenon, operating as a “family company.” Speaking about the company, Oliver is quoted: “It’s almost, like, not orphanage-y, but I want to see these energies succeed… New energy is very intimidating — it rewrites what has been created. We all get jaded by experiences in life, but I try to create environments for younger kids.” [Christopher Glazek, The New Yorker, September 5, 2016.]

A few days prior to New York Fashion Week last September, I came across an article in The New Yorker magazine that examined the creation of cult fashion label Hood By Air, which has become mainstream fashion’s latest obsession. Under the title “Hood by Air’s Radically Aggressive Streetwear,” the magazine’s Annals of Fashion section told the story of how the brand’s founder, Shayne Oliver, turned a small number of social outliers into a global phenomenon, operating as a “family company.” Speaking about the company, Oliver is quoted: “It’s almost, like, not orphanage-y, but I want to see these energies succeed… New energy is very intimidating — it rewrites what has been created. We all get jaded by experiences in life, but I try to create environments for younger kids.” [Christopher Glazek, The New Yorker, September 5, 2016.]

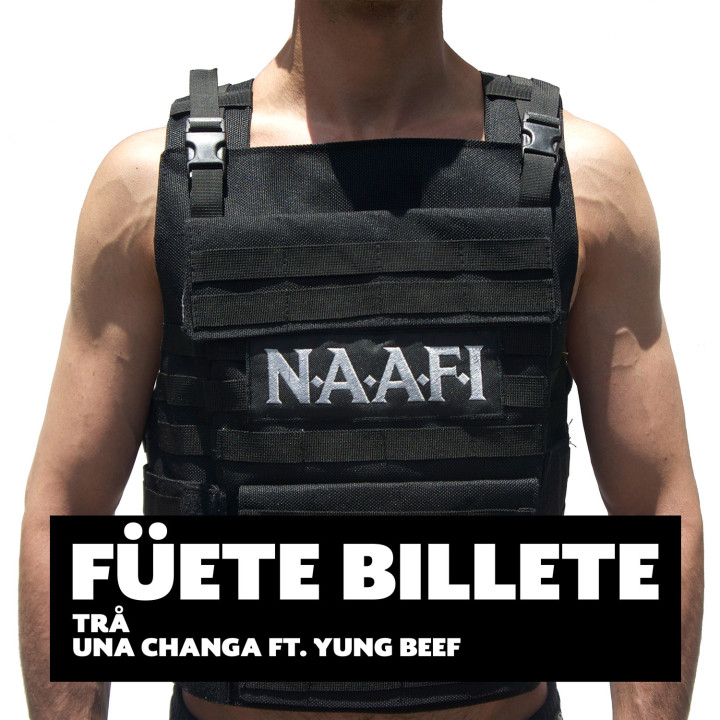

I shared the article with Alberto Bustamante, founding member and creative director of N.A.A.F.I, a Mexico City–based music label whose wide-ranging activities have also involved a unique group of norm-defying creatives since the project launched in 2010. Alberto replied, simply saying: “A shared principle between N.A.A.F.I and the way the article portrays H.B.A. is that we both understand our projects as a family.”

Only a few days later the concept of “family” became the main topic of the national political conversation. Just as Donald Trump was unexpectedly visiting Mexico City to meet with the unpopular president Enrique Peña Nieto, a homegrown conservative group identifying itself as the Frente Nacional por la Familia (National Front for the Family), whose stated aim is to revoke same-sex marriage laws, was preparing to take to the streets to “defend the natural family.” In a matter of days, social media was flooded with baffling propaganda from a far-right group that uses hashtags such as #defendemoslafamilia (#wedefendthefamily) and #notemetasconmishijos (#dontmesswithmykids), revealing the deep and horrifying conservatism still prevalent in Mexico.

To describe N.A.A.F.I as merely a music label would be reductive to say the least (the acronym is often construed as “No Ambition And Fuck-all Interest,” though it is in fact based on the UK’s Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes organization, which was created to provide recreational establishments for the British Armed Forces). The N.A.A.F.I family — cofounded by Oaxaca natives Alberto Bustamante (a.k.a. Mexican Jihad) and Tomás Davó (a.k.a. Fausto Bahía), and later joined by its other core members Lauro Robles (a.k.a. LAO) from Mexico City and Paul Marmota from Santiago — developed out of a shared ambition to redefine the music and party scene in Mexico at a critical moment in the country’s social and political history. But having seen the project evolve since its first events in 2010, the group’s influence and interests clearly extend beyond the party scene. N.A.A.F.I is today regarded as an open community that profoundly rejects Mexico’s normative ideals. Taking aim at local government as well as conservative groups such as the Frente Nacional por la Familia, N.A.A.F.I has developed its model away from strictly nocturnal activities in off-limit spaces to a multidisciplinary project with a potent political tenor, releasing records produced by its collective of fifteen or so artists, as well as branded apparel, merchandise and impeccably produced videos. It makes live appearances at such major music festivals as the Vive Latino, and has collaborated with cultural institutions such as the Museo Jumex and the Centro de Cultura Digital. N.A.A.F.I hosts Internet-based radio programs, voguing competitions, and even arranged a parade car for friends and family during this year’s Pride in Mexico City.

N.A.A.F.I began hosting its events within an entirely different national political climate, during the second tenure of the right-wing PAN party under Felipe Calderón, the president who famously declared the War on Drugs with disastrous consequences. Mexico’s militarization over those years led to nationwide insecurity, prompting many cities to implement nighttime curfews and pushing a generation of young Mexicans to spend their nights indoors. In Mexico City, where the Calderón years were lived differently due to the city’s governing police force, clubs nonetheless were forced to change their opening hours, leading to a downturn in the fortunes of the party scene. With the night demonized, N.A.A.F.I began to host underground parties that offered a new style of politically infused music, often incorporating Calderón’s speeches in its mix, and taking its cue from the indoor party scenes of conflict cities like Ecatepec, Ciudad Juárez and Mexicali.

In its reaction to the national political situation over the last six years, with its unmistakable tone of irreverence that maintains a tangible sense of urgency, N.A.A.F.I has been a voice for the rejection of the corrupt, heteronormative, narco state of Mexico while simultaneously offering a haven for a generation of young, curious and creative individuals who have shared in the discomfort. It has provided the sound track for a moment of high anxiety and, with its friends, such as fashion label Barragán and the editorial project i-D Mexico, they have also constructed a stylistic vision to match.

Earlier this year N.A.A.F.I hosted its first Cumbre Latinx, at which they gathered peers from Latin America who share in the group’s principles and vision. At a time when immigration has become a global talking point, this collective has presented themselves as a unified transnational movement. (The event’s shared identity was evident in the stitching together of the flags of the four participating countries: Uruguay, Chile, Argentina and Mexico). While rooted in their local context, N.A.A.F.I’s message is one of a globally mindful community keen to critique Western interventions by positioning itself at the center of cultural discourse (a T-shirt depicting Trump’s disfigured face alongside the group’s logo is a good example of their savvy appropriation of political content).

A recent visit to the Mangueira School of Samba in Rio de Janeiro introduced me for the first time to Brazil’s Carnival culture. The heavily branded, all-age and over-the-top samba rehearsal event I attended in Mangueira somehow made me think of that family that Alberto mentioned when he spoke about Hood By Air and the way he, Tomás, Lauro and Paul understand N.A.A.F.I. The live music and energetic dancing of Mangueira filled the space with a collective energy that I had only experienced in a few N.A.A.F.I events.

It is striking that open and inclusive spaces such as these can coexist when surrounded by the harshness of reality. N.A.A.F.I actively attempts to redefine our normative conception of the family while constructing a fertile world within which it can grow and develop. By not restricting themselves to easy identification as purely a music label, fashion house, art collective or party, the N.A.A.F.I family has been able to grow itself in a truly vital way. The value in their efforts lies in the way they’ve carved out their own space to secure an open environment for others to join in. Like the Hood By Air family, N.A.A.F.I’s next step is to make that safe space mainstream.