At the 1920 Dada Festival in Paris, André Breton wore a sign made by Francis Picabia, a drawing of a target surrounded by these words: “For you to like something, you must have seen or heard it for a long time, you bunch of idiots.” The sign indirectly addresses the perpetual challenge of identifying the artistic and formal revolutions that are under way at any given moment. This may explain why the ongoing expansion of the territory of contemporary art initiated by Mohamed Bourouissa in the early 2000s often goes unnoticed, even though his work has long been considered important. The treatment of each of his exhibitions as a “total” work of art, or as a means of extending thought into space, also adds to its complexity.

“Signal” is built as a walk through an installation that evokes the idea of a garden or park. Stripped from any aestheticizing dimension, it is materialized in space by the distribution in space of the artworks, the presence of white wooden structures reminiscent of Bourouissa’s previous explorations — as seen in the Liverpool Biennial and the Marcel Duchamp Prize exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, both in 2018 — an abundance of plants, and the repetition of the grid motif, notably in Sensibilité matière et grille (2024), a steel-and-aluminum work that is repeated six times. The exhibition merges this architectural dimension, rooted in the ideas of Frantz Fanon, with the multifaceted notion of the “signal” that permeates the space.

In the center of the path, low-growing plants emerge from a floor of potting soil covered with wood shavings; within spaces delineated by white structures, sculptural works reminiscent of equestrian or commemorative statues in public gardens reverse the meaning of these academic figures. For instance, Caleb on the horse (2018), a 2.7-meter-high sculptural work made from black polylactic acid polymer, gelatin silver prints on galvanized steel and horse straps of a young man from racially marginalized suburbs of Philadelphia, say, or Paris, is perched on elements reminiscent of motorbike debris. Large vertical video monitors directly positioned within the planted areas delve deeper into the deconstruction process by challenging the concept of sculpture itself, grounding it in hyper-contemporaneity through the transformation of video characters into quasi-sculptural elements.

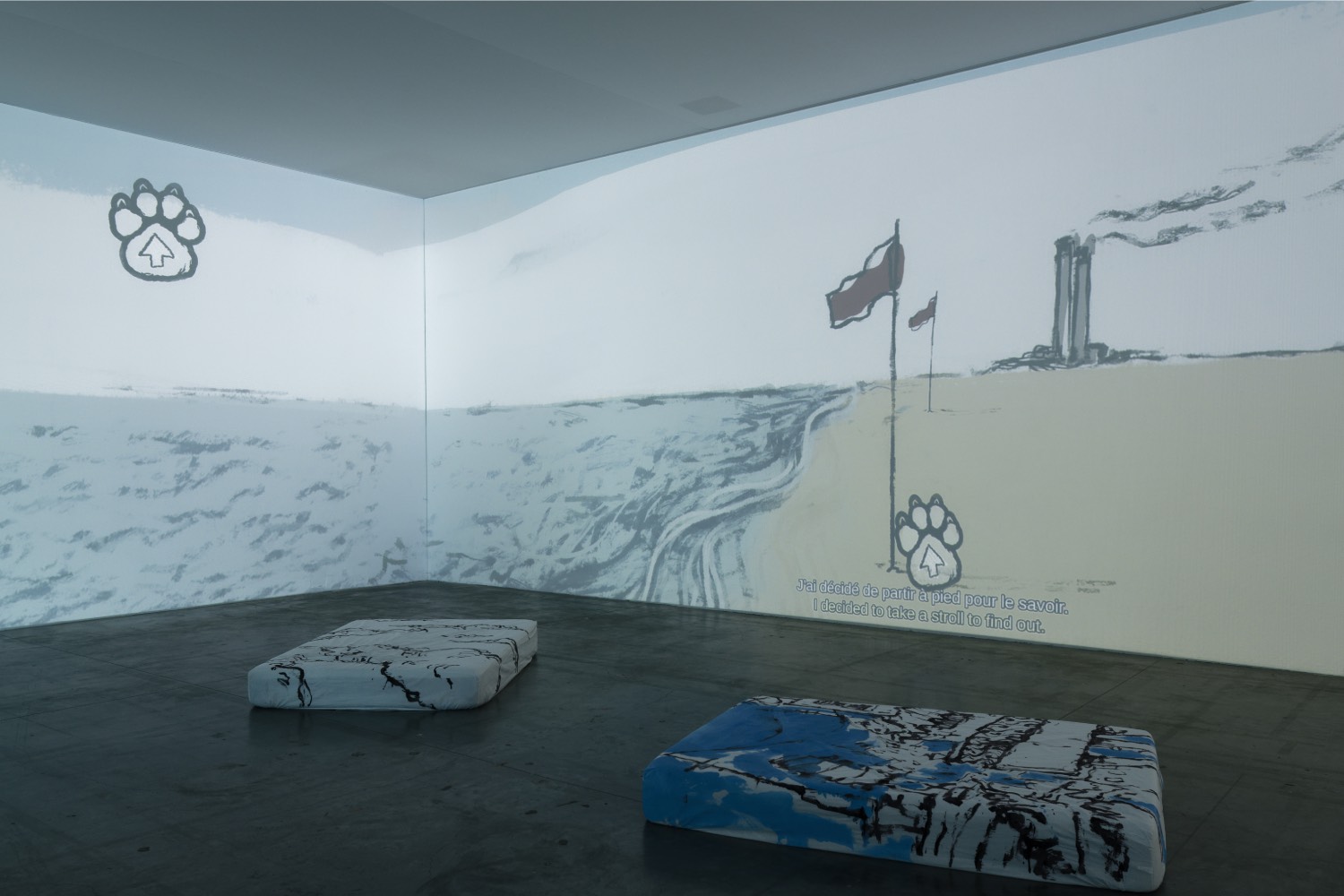

These looped videos are repeated on all screens scattered throughout the exhibition, including the three that adorn Oiseaux du Paradis (2023–24), which evocates a deconstructed white gazebo or a building’s silhouette topped with loudspeakers. Meanwhile, Brutal Family Roots (2020–23), an extensive installation on yellow carpeting, saturates the sound atmosphere. Its ensemble of twenty mimosa trees, potted in black oil drums on wheels, is connected to speakers capturing their sounds, which are then mixed into the music heard throughout the exhibition in the form of a playlist.

In Black Skin, White Masks (1952), Frantz Fanon theorized the necessity of examining past colonial traumas, defined the quote from Aimé Césaire that opens the book: “I am talking of millions of men who have been skillfully injected with fear, inferiority complexes, trepidation, servility, despair, abasement.” This analysis is essential for comprehending the psychological, emotional, and physical condition of both the formerly colonized and their descendants. The oldest patient at the psychiatric hospital where Fanon practiced in Blida (Bourouissa’s birthplace) introduced the artist to the architectural practice of the garden, conceived as a place of resilience and projection of thought in space.

The intersection of this axis with the notion of signal, in an evocation that bridges the most personal with the most universal, intertwines additional narratives within the visitor’s garden stroll. Genéalogie de la violence (2023) is an animated film depicting a young couple’s innocent rendezvous in a car, interrupted by the arrest of the young innocent man during a police check is its climax. The psychological impact of the arrest is narrated in a voice-over, as well as by some images of the young man’s inner body. A series of other works, such as Mehdi Anede(2023), featuring two cast aluminum arms whose hands are pressed against a wall as if during a body search, and the “Seum” series (2024), which overlays a photographic work on acetate with a watercolor, resonate with the experiences of young, racialized men from disadvantaged suburbs.

Yet Bourouissa’s prolific body of work constantly transcends these boundaries, as also exemplified in this extensive retrospective. The sumptuous Lila (2023–24), a ten-meter-long L-shaped display case crafted from red, orange, and blue plexiglass, forms a sculptural tableau intricately woven around the grid motif. This Large Glass repurposes elements and materials from the studio, echoing the construction of the exhibition, also evoked by Idriss (2023), a cast aluminum work repeated three times. Additionally, a large-format photograph, illuminated by a red light bulb, captures the tattooed arm of the elderly patient from the Blida psychiatric hospital. He rolls up his sleeve in a gesture of exposure, thus encapsulating the remarkable coherence of this exhibition and its movement toward a new form.