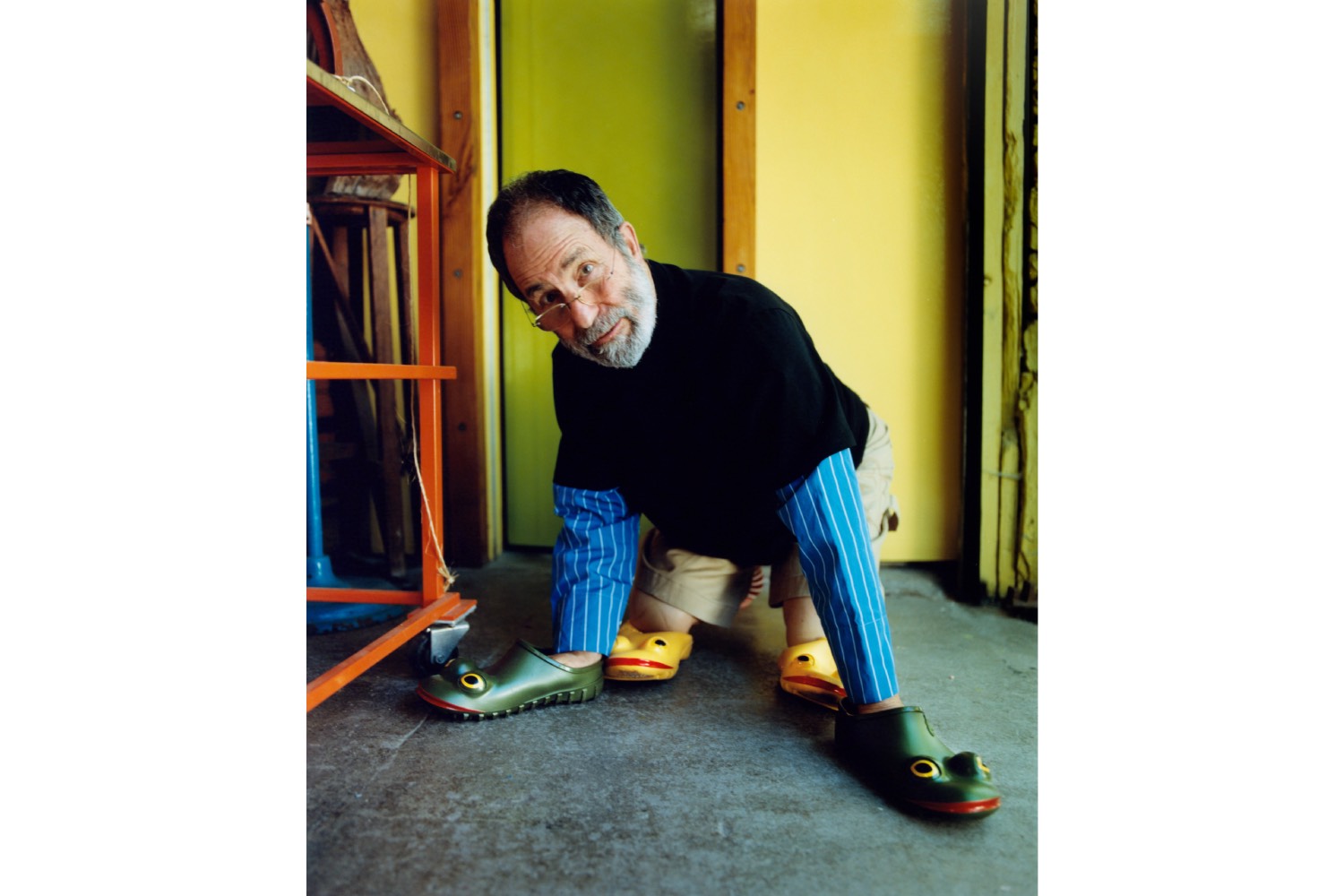

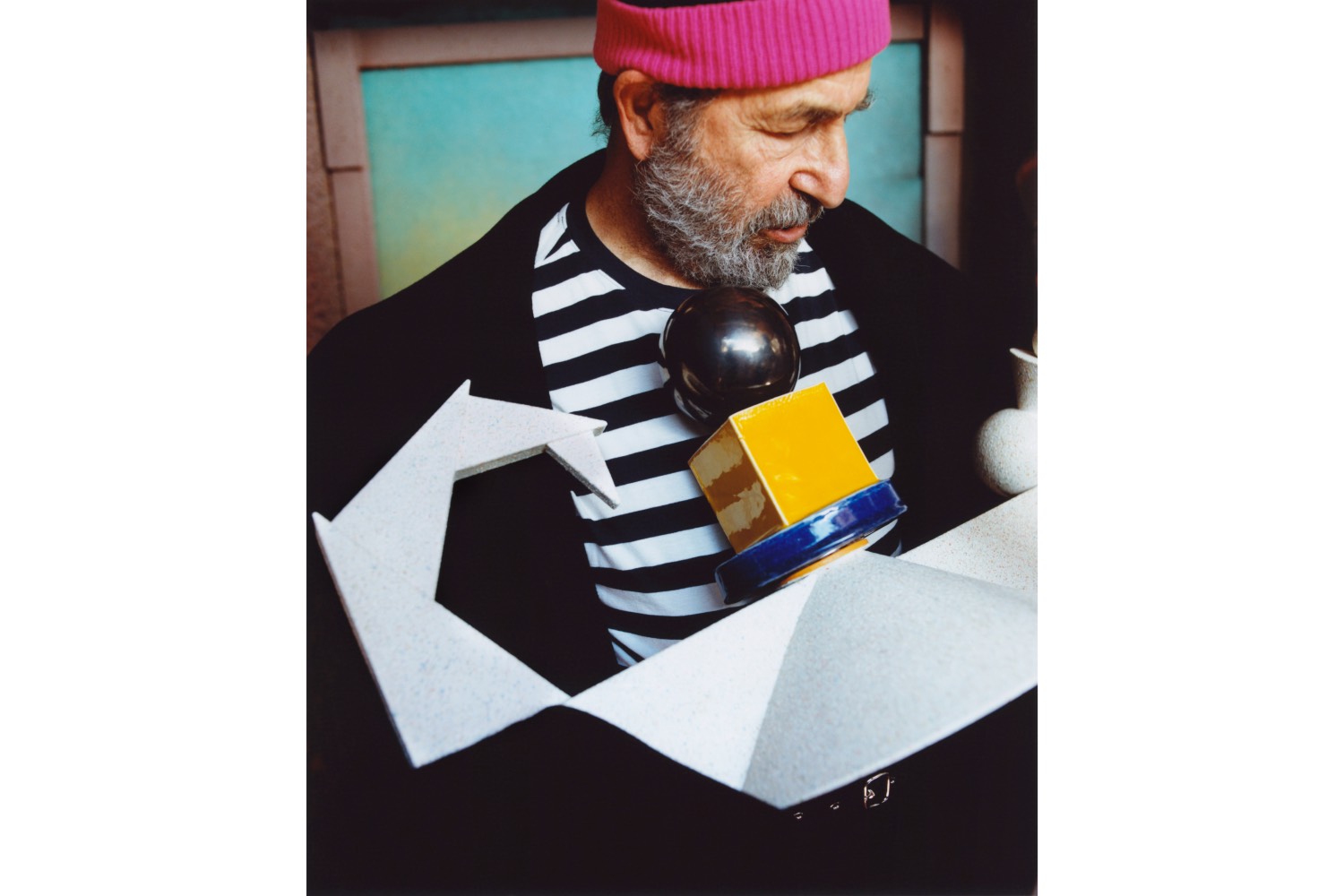

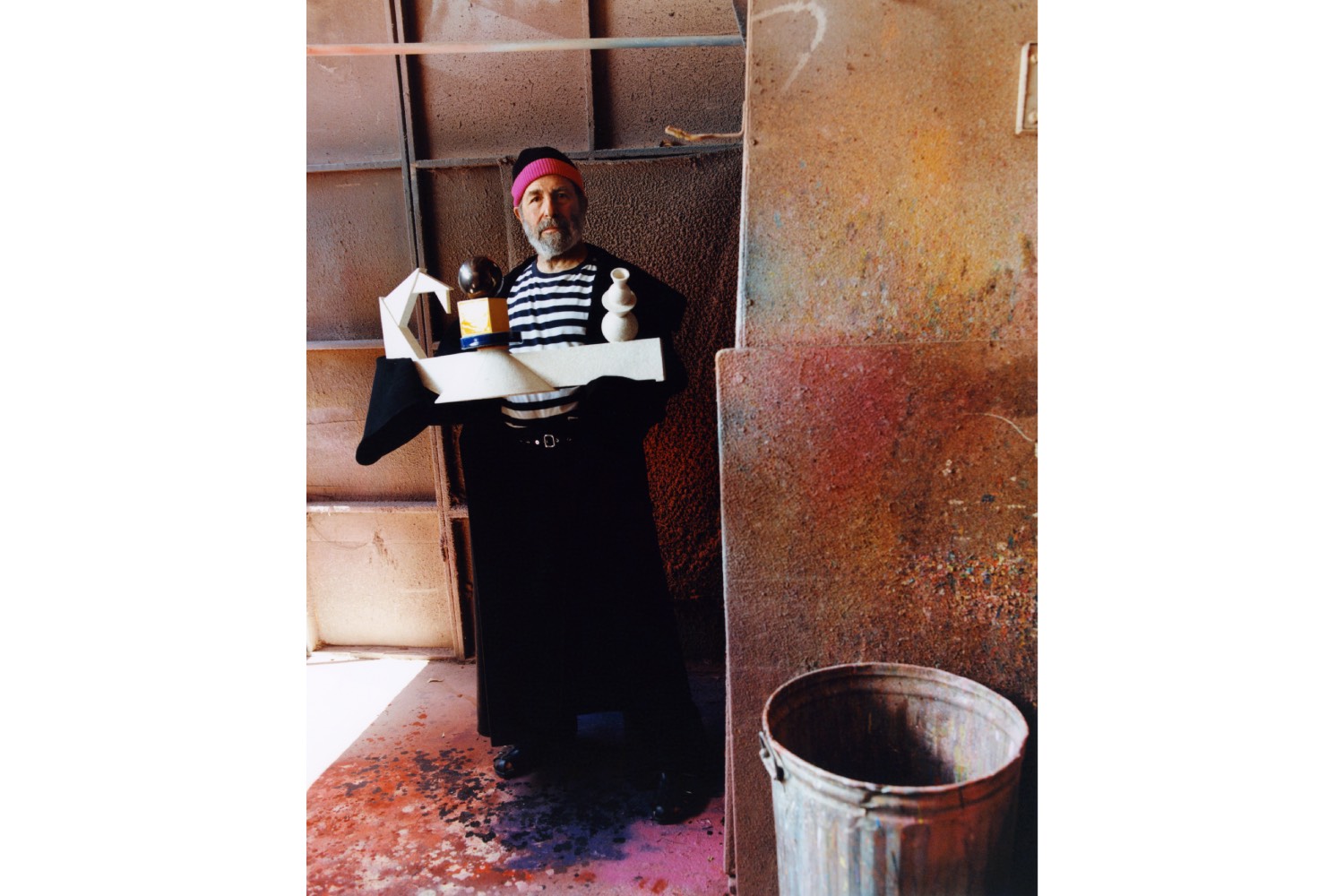

As Peter Shire describes it, it’s “just another bucolic afternoon in Echo Park, Los Angeles, with the cars making whooshing sounds as they go by. And that helicopter that came by. I think we are really pushing the boundaries, as it were, with the fashion-art thing.” I first met Shire in 2016 and buzzed by his studio like many of us do. He and Donna Shire, his wife, welcomed me, and I stayed the whole day, sipping about ten Portioli espressos and killing thirst with San Pellegrino. I am back now, and Peter’s studio looks the same: more objects, new colorful wobbly chairs, and more DIY furniture that he could easily sell — even the toilet sink, which is handmade. We sat down at lunch, ate Donna’s salad and broccoletti, and discussed God as Mickey Mouse.

Gea Politi: Is there anything people never ask you in an interview?

Peter Shire: They never ask me how I am.

GP How are you?

PS Well, okay.

GP That’s a nice ending, too, instead of a beginning.

PS Well, that’s the Marcel Duchamp ending, right?

GP We will do a bit of Bacon-style, a bit of Duchamp, a bit of Shire.

PS Yes, we had to bring home the bacon.

GP From an accident in your work to how you feel.

PS That is a weird one. They did a Q&A with Gaetano Pesce at the Italian Cultural Institute, and one woman had one of his big rubber tables. She said, “Oh, my kids eat breakfast on it, and they’ve ruined it. They’ve taken chunks out of it. What do you think of that?” And he said, “Well, it’s part of life. It’s all fine.” I thought that was a pretty diplomatic answer.

GP I mean, it’s your problem: you have destroyed a Gaetano Pesce. Were you close to him?

PS No, I was around him only a couple of times.

GP Were you sad when he passed?

PS Yes, it’s a rough one because we’re entering the most significant questions: How do you deal with death? We’ve lost so many people in the last three years. It’s just crazy. And you’re younger than me, so it isn’t about me being older now. Are you good with memory?

GP It’s a hot topic. I’m not good at it, and it must have something to do with my lazy eye. Did you ever define yourself, Peter? What are you: an artist, a potter, a designer, a weirdo?

PS Yes, I am WOW. That was it. Wow. Well, it’s based on so many things. We use a lot of words that we’ve kind of vamped up, like judgment, branding, and marketing. When somebody says, “Don’t judge me,” we know what they mean, but they aren’t saying what they really mean. What they are actually saying is, “Don’t shoot at me.”

GP People want to specialize in something.

PS Or have a practice. Since when did artists have practices? Lawyers have practices. Dentists have practices. I mean, where’s the romance? Being an artist is an adventure, a calling, a romance. Definitions must deal with categorizing and judgments of a sort, which we, within a cultural context, do one way or the other. I always joke: if you like designers, then I’m a designer, and if you don’t like designers, then I’m an artist or whatever.

I heard Steve Allen speak to the first commencement of CalArts, oddly enough, and he said, “Well, you all feel like you’re hot, and you’re going to go out and take the art world by storm and be artists. You’re all artists.” And you could hear the murmur in the crowd: “Yes.” Up with the flag. And then he added, “But just remember, you may have to have a job to pay your rent. And when you’re pumping gas, you’re a gas station attendant. And when you’re a father, you’re a father.”

GP We tend to forget about that.

PS I do several of these activities, and my design activity is funny because I’m not a commercial designer or a real designer. I don’t do products for a company. And within the definition of design, it comes from the fact that we were all craftsmen. Back in the day, when we made things — bowls, candlesticks, whatever it was — some people had an idea, and they were outstanding. That’s when you start to get your Segusos and your Vistosis. They move into a whole design house. But even then, they’re craftsmen, and once it was taken away from people’s hands and into an idea of abstraction, drawing a technical drawing for a machine to make it, it became design, because Michelangelo talked about his designs for the Sistine Chapel. He also called them cartoons, which is very funny, right? Mickey Mouse giving the word of God to Moses. To Mickey Moses.

GP Some people claim that Mickey Mouse was born before God.

PS He’s undoubtedly more ubiquitous. God, John Lennon got killed for that. Anyway, I love Mickey. I’ve made peace with Walt Disney.

GP What part of your work do you like to do the most?

PS Well, I’d say drawing because that’s what I’m doing on my own. And then ceramics. I’m reasonably good at it, and it’s really satisfying. As for the metalwork, I’m a good assistant. I really don’t weld, so I’ve just started having to do that, too. What would you call me? I guess I should have some sort of weird existential euphemistic description: I’m a dealer, and I deal in the metaphysical gestalt of real objects that aren’t real or something like that.

GP I once read that Ettore Sottsass discovered your work through WET magazine.

PS That’s right. I didn’t know that for years.

GP Then he invited you to Italy.

PS Well, he showed up because he had sent Aldo Cibic and Matteo Thun to do an article for Casa Vogue with Isa Vercelloni. When they showed up, I thought, “Whoa, I love these guys.” And Matteo said, “You must come to Italy.”

GP That was what, the mid-1970s or something?

PS It was like 1977 or 1978. And so, I said, “Well, I’m going to come.” Ettore came to LA a few months later, and we went to lunch. He loved Chinese food. We went to eat, and luckily, we had this Chinese restaurant we were always going to, so I was doing very well. And we were back at my studio, and I was working up the nerve to say, “I’m going to come to Italy,” or “Should I come to Italy?” And he turned to me before I’d said anything and said, “So when will you be in Italy?”

GP And so then you went, and you contributed.

PS I bought my ticket six months in advance.

GP You basically became part of or were already part of the Memphis movement. And I mean, did that change your journey?

PS Well, another one of the words we always use is… absolutely. Did it change? Absolutely.

GP I mean, everything you do changes your journey.

PS I mean, it’s more than that. I knew it was something at the time, but I didn’t realize just how much. They said they wanted me to work with Alchimia. Alchimia was a loose and groovy outfit. And then Barbara [Radice] called and said, “We’re going to leave Alchimia, and we’re going to do this. Will you come with us?” And immediately, I said, “Of course. Wherever you are, wherever Ettore is, I will be there.”

GP It was very spontaneous.

PS Yes. Have you ever seen The Little Rascals? There’s this scene, “Hey, kids, let’s do a show.” Or, “Hey, let’s go for a picnic. Get your lunch. We’ll get on the bus.” And similarly spontaneous, there I was. This collaboration is going to be something where everybody says: he did this, or all of that. And then, of course, that’s what it was. So, it’s a weird thing because now people want to do things, and I have the same spontaneous tendency to say, “Yes, let’s do it.” Then you’re going, “Oh, wait a minute.” People are coming at me. At that time, Ettore was something, but the rest of us were young and didn’t have a reputation to protect or have people wanting to take advantage of us. But it really was an influence because I believe we were all watching each other. There was suddenly a fantastically cohesive group. It really speaks to Ettore. I mean, can you imagine? Basically, he wrote an essay about why the pen was his father’s tool and the airplane was his tool. And he was going all over the world looking for a group. And he made this group. When you think about it, every one of us is doing something. There isn’t one that branched off into being a CPA or a businessman or something. Everyone is doing something.

GP Well, they kind of coexisted naturally in the same moment, and somehow also without communicating at the beginning.

PS Well, actually, there was more communication. You don’t think about it at the time. I’d gone into the school library at Chouinard, and they had magazines, they had Domus. And, of course, that was love at first sight, and what made it even better was that I couldn’t read it. It was giddy. Upside down and right side up. It was crazy. And then once I got there, and Ettore had this room with an accordion door and a whole bunch of stuff he’d done, I said, “Oh yeah, that.” That was him.

GP The first time I came to meet you at your studio, there was a whole international point of view. It wasn’t California or Echo Park, necessarily. I’ve always thought, “Wow, actually, he lives here, but he doesn’t live in a bubble.”

PS And the crazy part is I’ve lived here all my life and have never lived anywhere else.

GP And you are not an outsider.

PS I know. Thank you.

GP You feel like it’s a very local area of Los Angeles, but it’s also highly international, and you touch so many different styles and vibrations. So, for me, this is quite fascinating about your work. I don’t know if you want to say something about it.

PS Well, I think you said it pretty well.

GP Do you actually believe in accidents while making art?

PS Oh. Have you ever asked anyone that before?

GP No But I know who asked it, and I love this question. It was David Sylvester who asked Bacon.

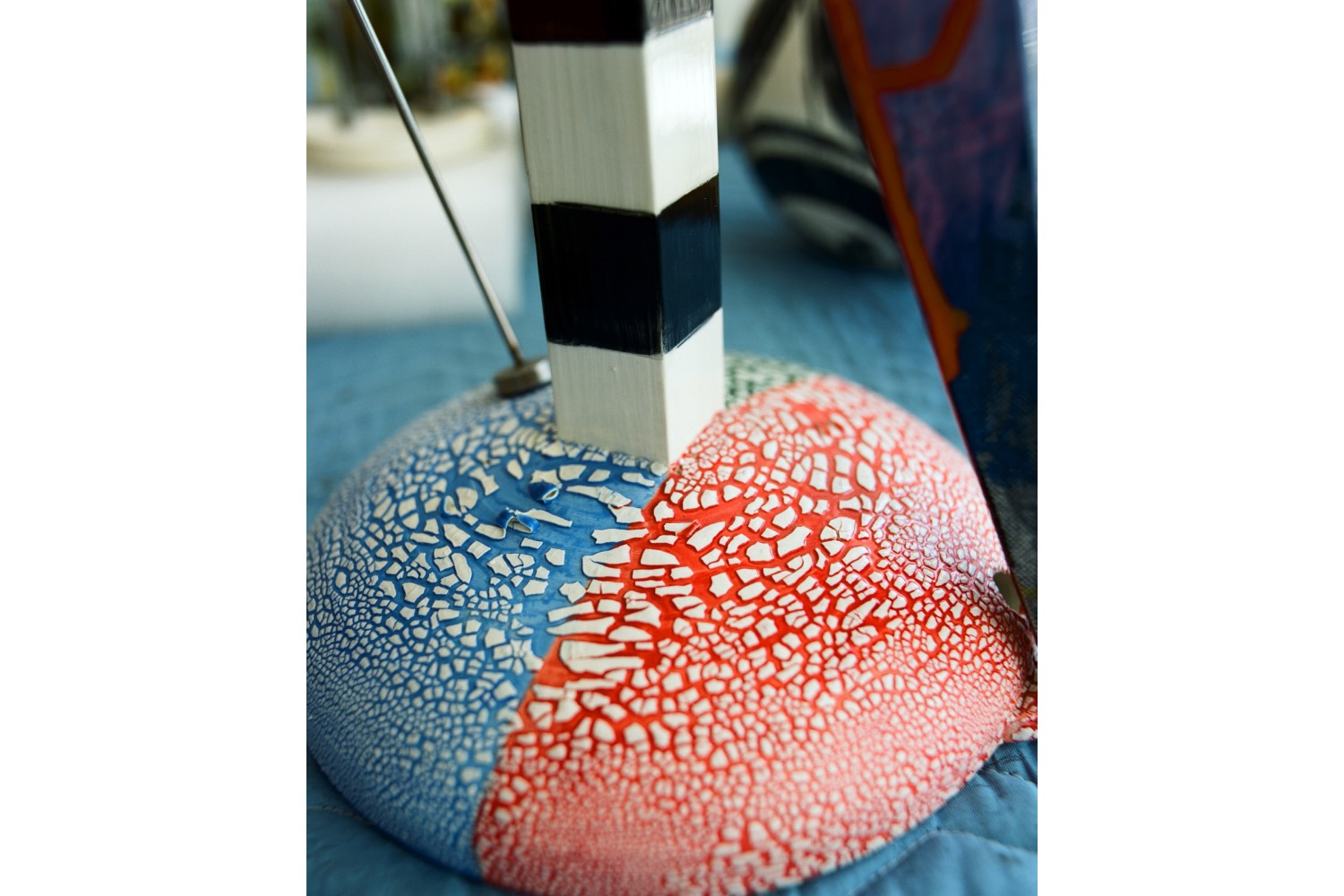

PS Oh, well, we’re even more inclined to in ceramics. First, there’s the controlled accident. That’s one of the key factors in ceramics because you can’t control the fire; you can direct it, but you’re waiting to see the result: it’s actually a ceramicist’s phrase, “the controlled accident.” Of course, people want to know, “What’s the creative process?” And it’s sort of an impossible question: How can I get it? How long does it take to get it? Can I mail away for it? And, like many things, there’s no way to get it. You could say you either have it or you don’t.

And so, the upshot is that creativity is a number of things. You build a house, you build a stairway, you’re creating, et cetera. Having a child, I mean, is the ultimate one, right? But when you talk about the creative process, this is where the weird glitch is because there’s this deal that people talk about: creatives. Is that a job description? Well, it is now in a funny way, but what even is that? And for me, it’s just what you asked: Is a leap of faith an accident? There’s a moment where you’re going to make a plate yellow, and you think, “But if I put a little green,” or you see a little green on the salad plate next door, and you go with it. That instant is when you allow yourself off the track to see beyond. And that is freedom. You know what I’m saying? In other words, we think of freedom as if we could fly or something. We think of freedom as an ultimate abstract state that defies gravity — using gravity as a broad term for everything. So, if you mail it to me with $5.95, I will send you the answer. And if you don’t mail it to me, five of your relatives will die.

GP So we talked briefly and funnily about design week in Milan.

PS Our society is overloaded.

GP Overloaded. Design, fashion, and art have responsibilities, but in different ways. And now they’re becoming increasingly interconnected. It’s been a while, actually, not just now.

PS Well, one of the things to point out is that fashion gets the subtext industry, and design is connected to industry, but art IS the hyperlink. And it doesn’t have a hypertext. It’s a funny modifier. And it doesn’t have an industry.

GP Art is the justification of art, fashion, and design to go deeper into something.

PS Cultural, sociological, or socioeconomic are probably more symbolic.

GP Exactly, which means more semantic depth or meaning.

PS Yes. Attaching meanings that relate to the throw of life.

GP Have you ever thought about your work as being therapeutic?

PS Yes. I think of all the money I’ve saved on therapy.

GP Your work kind of moved into different patterns. From the mid-1970s, you shifted into the pattern-and-decoration world. Can we say that? This period also belonged to artists such as Miriam Schapiro and Robert Kushner.

PS And Kim MacConnel, Jackson Pollock. Plaid, stripes, polka dots, fabric patterns, and checks — especially when they come in the mail.

GP Yes, exactly. Also, Joyce Kozloff. Was this another significant shift in your life, would you say?

PS Well, that’s the same thing with the international. I just love everything except the things I don’t love.

GP Oh, right. That’s very interesting because this is exactly what I’m saying. Then there was this moment when you kind of embraced the kitsch if we can say so. I didn’t like kitsch, but I argued so long with myself that I had to like it.

PS I always have liked it. There’s a great saying from Isaac Bashevis Singer: “We haggled so long, we laid down together.”

GP Totally. And so, is there something that you can define as vulgar or tacky for you, or nothing is?

PS The place I’d start is that, again, kitsch is a word people throw around. And it’s often used correctly because it’s in context. But ask someone to define it, and they’d go, “I can’t define it, but I know what it is.” I read different definitions, and the one that seemed most to the point was: the substitution of real values for spurious values, i.e., plastic flowers. Then we kind of go into a circle. We get something that’s referred to as high kitsch, or camp, where we appreciate it for being vulgar, and even the sociological context that it’s attached to, and maybe even laughing up our sleeve at it. Do you know that expression?

GP Feeling superior about things.

PS Yeah. Feeling superior and so forth. I don’t love this; I just realized how kitsch it is.

GP So you designed the first Bel Air chair in 1980? And then again, this is what I read: it took you around thirty years to create the next one, which was like the Bel Air. And then the Brentwood came in 2017. I wanted to understand because it takes more than seven years to design.

PS And thank God if you even do one.

GP Right? That’s what I was getting at. First of all, I was very interested in your reaction to the first chair when it came out.

PS I usually send in twenty to thirty thumbnail sketches of the pieces because I was working from here, and there was no discussion. I’d number them 15 and 12.

GP Right?! And you were working from your bubble here.

PS I was working from my bubble and my fresh LA air. The upshot is that if there was a response to one of the designs, it was a stand-out — maybe even a great piece. So far, I’ve met three people who have tattoos of the chair. They have it tattooed on them!

GP So the Bel Air was also the Bone Air?

PS Yeah. I had put Bone Air, Larry Garcia, a friend, and I thought that was hilarious.

GP Is there a piece of design that you ever wanted to make yourself that isn’t yours?

PS There are boxes of them, of course. And you know what I say when I see them? “I hate you.”

GP There was some time between designing chairs.

PS Well, it became of interest to explore the form after a while. The same with the Brazil table, which I’m not sure what I named it. It was very funny. I had done the top magenta, but when I saw it, they had done it in yellow. So, I thought, “Should I get mad at somebody or be an asshole?” And I thought, “No, I’d just be being a jerk. Why bother?” George Sowden, the project architect, did a number of things with the interpretation of it. And now that I think about it, its colors are the colors of Brazil. The yellow top, the green fin, the black. The last time I saw Sowden, we were talking, and he said, “I’d always heard that you were mad at me for the colors.” I thought, “Wow, who would have told them that?” I told him, “No,” which is the case, “I’m not mad at you at all. I was a little bit shocked, and I realized over the years that the most beneficial thing I did was leaving those colors alone.”

GP Leaving those colors alone. Is there any color that you actually left alone?

PS Oh yeah, brown.